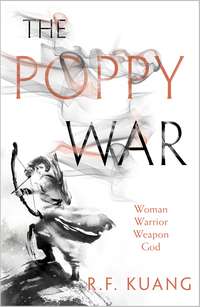

The Poppy War

Rin was so relieved that she had to remember to look properly chastised. “No. I mean, I don’t.”

“Do you think it will be so bad?” Auntie Fang’s voice became dangerously quiet. “What is it, really? Are you afraid of sharing his bed?”

Rin hadn’t even considered that, but now the very thought of it made her throat close up.

Auntie Fang’s lip curled in amusement. “The first night is the worst, I’ll give you that. Keep a wad of cotton in your mouth so you don’t bite your tongue. Do not cry out, unless he wants you to. Keep your head down and do as he says—become his mute little household slave until he trusts you. But once he does? You start plying him with opium—just a little bit at first, though I doubt he’s never smoked before. Then you give him more and more every day. Do it at night right after he’s finished with you, so he always associates it with pleasure and power.

“Give him more and more until he is fully dependent on it, and on you. Let it destroy his body and mind. You’ll be more or less married to a breathing corpse, yes, but you will have his riches, his estates, and his power.” Auntie Fang tilted her head. “Then will it hurt you so much to share his bed?”

Rin wanted to vomit. “But I …”

“Is it the children you’re afraid of?” Auntie Fang cocked her head. “There are ways to kill them in the womb. You work in the apothecary. You know that. But you’ll want to give him at least one son. Cement your position as his first wife, so he can’t fritter his assets on a concubine.”

“But I don’t want that,” Rin choked out. I don’t want to be like you.

“And who cares what you want?” Auntie Fang asked softly. “You are a war orphan. You have no parents, no standing, and no connections. You’re lucky the inspector doesn’t care that you’re not pretty, only that you’re young. This is the best I can do for you. There will be no more chances.”

“But the Keju—”

“But the Keju,” Auntie Fang mimicked. “When did you get so deluded? You think you’re going to an academy?”

“I do think so.” Rin straightened her back, tried to inject confidence into her words. Calm down. You still have leverage. “And you’ll let me. Because one day, the authorities might start asking where the opium’s coming from.”

Auntie Fang examined her for a long moment. “Do you want to die?” she asked.

Rin knew that wasn’t an empty threat. Auntie Fang was more than willing to tie up her loose ends. Rin had watched her do it before. She’d spent most of her life trying to make sure she never became a loose end.

But now she could fight back.

“If I go missing, then Tutor Feyrik will tell the authorities precisely what happened to me,” she said loudly. “And he’ll tell your son what you’ve done.”

“Kesegi won’t care,” Auntie Fang scoffed.

“I raised Kesegi. He loves me,” Rin said. “And you love him. You don’t want him to know what you do. That’s why you don’t send him to the shop. And why you make me keep him in our room when you go out to meet your smugglers.”

That did it. Auntie Fang stared at her, mouth agape, nostrils flaring.

“Let me at least try,” Rin begged. “It can’t hurt you to let me study. If I pass, then you’ll at least be rid of me—and if I fail, you still have a bride.”

Auntie Fang grabbed at the wok. Rin tensed instinctively, but Auntie Fang only resumed scrubbing it with a vengeance.

“You study in the shop, and I’ll throw you out on the streets,” Auntie Fang said. “I don’t need this getting back to the inspector.”

“Deal,” Rin lied through her teeth.

Auntie Fang snorted. “And what happens if you get in? Who’s going to pay your tuition, your dear, impoverished tutor?”

Rin hesitated. She’d been hoping the Fangs might give her the dowry money as tuition, but she could see now that had been an idiotic hope.

“Tuition at Sinegard is free,” she pointed out.

Auntie Fang laughed out loud. “Sinegard! You think you’re going to test into Sinegard?”

Rin lifted her chin. “I could.”

The military academy at Sinegard was the most prestigious institution in the Empire, a training ground for future generals and statesmen. It rarely recruited from the rural south, if ever.

“You are deluded.” Auntie Fang snorted again. “Fine—study if you like, if that makes you happy. By all means, take the Keju. But when you fail, you will marry that inspector. And you will be grateful.”

That night, cradling a stolen candle on the floor of the cramped bedroom that she shared with Kesegi, Rin cracked open her first Keju primer.

The Keju tested the Four Noble Subjects: history, mathematics, logic, and the Classics. The imperial bureaucracy in Sinegard considered these subjects integral to the development of a scholar and a statesman. Rin had to learn them all by her sixteenth birthday.

She set a tight schedule for herself: she was to finish at least two books every week, and to rotate between two subjects each day. Each night after she had closed up shop, she ran to Tutor Feyrik’s house before returning home, arms laden with more books.

History was the easiest to learn. Nikan’s history was a highly entertaining saga of constant warfare. The Empire had been formed a millennium ago under the mighty sword of the merciless Red Emperor, who destroyed the monastic orders scattered across the continent and created a unified state of unprecedented size. It was the first time the Nikara people had ever conceived of themselves as a single nation. The Red Emperor standardized the Nikara language, issued a uniform set of weights and measurements, and built a system of roads that connected his sprawling territory.

But the newly conceived Nikara Empire did not survive the Red Emperor’s death. His many heirs turned the country into a bloody mess during the Era of Warring States that followed, which divided Nikan into twelve rival provinces.

Since then, the massive country had been reunified, conquered, exploited, shattered, and then unified again. Nikan had in turn been at war with the khans of the northern Hinterlands and the tall westerners from across the great sea. Both times Nikan had proven itself too massive to suffer foreign occupation for very long.

Of all Nikan’s attempted conquerors, the Federation of Mugen had come the closest. The island country had attacked Nikan at a time when domestic turmoil between the provinces was at its peak. It took two Poppy Wars and fifty years of bloody occupation for Nikan to win back its independence.

The Empress Su Daji, the last living member of the troika who had seized control of the state during the Second Poppy War, now ruled over a land of twelve provinces that had never quite managed to achieve the same unity that the Red Emperor had imposed.

The Nikara Empire had proven itself historically unconquerable. But it was also unstable and disunited, and the current spell of peace held no promise of durability.

If there was one thing Rin had learned about her country’s history, it was that the only permanent thing about the Nikara Empire was war.

The second subject, mathematics, was a slog. It wasn’t overly challenging but tedious and tiresome. The Keju did not filter for genius mathematicians but rather for students who could keep up things such as the country’s finances and balance books. Rin had been doing accounting for the Fangs since she could add. She was naturally apt at juggling large sums in her head. She still had to bring herself up to speed on the more abstract trigonometric theorems, which she assumed mattered for naval battles, but she found that learning those was pleasantly straightforward.

The third section, logic, was entirely foreign to her. The Keju posed logic riddles as open-ended questions. She flipped open a sample exam for practice. The first question read: “A scholar traveling a well-trodden road passes a pear tree. The tree is laden with fruit so heavy that the branches bend over with its weight. Yet he does not pick the fruit. Why?”

Because it’s not his pear tree, Rin thought immediately. Because the owner might be Auntie Fang and break his head open with a shovel. But those responses were either moral or contingent. The answer to the riddle had to be contained within the question itself. There must be some fallacy, some contradiction in the given scenario.

Rin had to think for a long while before she came up with the answer: If a tree by a well-traveled road has this much fruit, then there must be something wrong with the fruit.

The more she practiced, the more she came to see the questions as games. Cracking them was very rewarding. Rin drew diagrams in the dirt, studied the structures of syllogisms, and memorized the more common logical fallacies. Within months, she could answer these kinds of questions in mere seconds.

Her worst subject by far was Classics. It was the exception to her rotating schedule. She had to study Classics every day.

This section of the Keju required students to recite, analyze, and compare texts of a predetermined canon of twenty-seven books. These books were written not in the modern script but in the Old Nikara language, which was notorious for unpredictable grammar patterns and tricky pronunciations. The books contained poems, philosophical treatises, and essays on statecraft written by the legendary scholars of Nikan’s past. They were meant to shape the moral character of the nation’s future statesmen. And they were, without exception, hopelessly confusing.

Unlike with logic and mathematics, Rin could not reason her way out of Classics. Classics required a knowledge base that most students had been slowly building since they could read. In two years, Rin had to simulate more than five years of constant study.

To that end, she achieved extraordinary feats of rote memorization.

She recited backward while walking along the edges of the old defensive walls that encircled Tikany. She recited at double speed while hopping across posts over the lake. She mumbled to herself in the store, snapping in irritation whenever customers asked for her help. She would not let herself sleep unless she had recited that day’s lessons without error. She woke up chanting classical analects, which terrified Kesegi, who thought she had been possessed by ghosts. And in a way, she had been—she dreamed of ancient poems by long-dead voices and woke up shaking from nightmares where she’d gotten them wrong.

“The Way of Heaven operates unceasingly, and leaves no accumulation of its influence in any particular place, so that all things are brought to perfection by it … so does the Way operate, and all under the sky turn to them, and all within the seas submit to them.”

Rin put down Zhuangzi’s Annals and scowled. Not only did she have no idea what Zhuangzi was writing about, she also couldn’t see why he had insisted on writing in the most irritatingly verbose manner possible.

She understood very little of what she read. Even the scholars of Yuelu Mountain had trouble understanding the Classics; she could hardly be expected to glean their meaning on her own. And because she didn’t have the time or the training to delve deep into the texts—and since she could think of no useful mnemonics, no shortcuts to learning the Classics—she simply had to learn them word by word and hope that would be enough.

She walked everywhere with a book. She studied as she ate. When she tired, she conjured up images for herself, telling herself the story of the worst possible future.

You walk up the aisle in a dress that doesn’t fit you. You’re trembling. He’s waiting at the other end. He looks at you like you’re a juicy, fattened pig, a marbled slab of meat for his purchase. He spreads saliva over his dry lips. He doesn’t look away from you throughout the entire banquet. When it’s over, he carries you to his bedroom. He pushes you onto the sheets.

She shuddered. Squeezed her eyes shut. Reopened them and found her place on the page.

By Rin’s fifteenth birthday she held a vast quantity of ancient Nikara literature in her head, and could recite the majority of it. But she was still making mistakes: missing words, switching up complex clauses, mixing up the order of the stanzas.

This was good enough, she knew, to test into a teacher’s college or a medical academy. She suspected she might even test into the scholars’ institute at Yuelu Mountain, where the most brilliant minds in Nikan produced stunning works of literature and pondered the mysteries of the natural world.

But she could not afford any of those academies. She had to test into Sinegard. She had to test into the highest-scoring percentage of students not just in the village, but in the entire country. Otherwise, her two years of study would be wasted.

She had to make her memory perfect.

She stopped sleeping.

Her eyes became bloodshot, swollen. Her head swam from days of cramming. When she visited Tutor Feyrik at his home one night to pick up a new set of books, her gaze was desperate, unfocused. She stared past him as he spoke. His words drifted over her head like clouds; she barely registered his presence.

“Rin. Look at me.”

She inhaled sharply and willed her eyes to focus on his fuzzy form.

“How are you holding up?” he asked.

“I can’t do it,” she whispered. “I only have two more months, and I can’t do it. Everything is spilling out of my head as quickly as I put it in, and—” Her chest rose and fell very quickly.

“Oh, Rin.”

Words spilled from her mouth. She spoke without thinking. “What happens if I don’t pass? What if I get married after all? I guess I could kill him. Smother him in his sleep, you know? Would I inherit his fortune? That would be fine, wouldn’t it?” She began to laugh hysterically. Tears rolled down her cheeks. “It’s easier than doping him up. No one would ever know.”

Tutor Feyrik rose quickly and pulled out a stool. “Sit down, child.”

Rin trembled. “I can’t. I still have to get through Fuzi’s Analects before tomorrow.”

“Runin. Sit.”

She sank onto the stool.

Tutor Feyrik sat down opposite her and took her hands in his. “I’ll tell you a story,” he said. “Once, not too long ago, there lived a scholar from a very poor family. He was too weak to work long hours in the fields, and his only chance of providing for his parents in their old age was to win a government position so that he might receive a robust stipend. To do this, he had to matriculate at an academy. With the last of his earnings, the scholar bought a set of textbooks and registered for the Keju. He was very tired, because he toiled in the fields all day and could only study at night.”

Rin’s eyes fluttered shut. Her shoulders heaved, and she suppressed a yawn.

Tutor Feyrik snapped his fingers in front of her eyes. “The scholar had to find a way to stay awake. So he pinned the end of his braid to the ceiling, so that every time he drooped forward, his hair would yank at his scalp and the pain would awaken him.” Tutor Feyrik smiled sympathetically. “You’re almost there, Rin. Just a little further. Please do not commit spousal homicide.”

But she had stopped listening.

“The pain made him focus,” she said.

“That’s not really what I was trying to—”

“The pain made him focus,” she repeated.

Pain could make her focus.

So Rin kept a candle by her books, dripping hot wax on her arm if she nodded off. Her eyes would water in pain, she would wipe her tears away, and she would resume her studies.

The day she took the exam, her arms were covered with burn scars.

Afterward, Tutor Feyrik asked her how the test went. She couldn’t tell him. Days later, she couldn’t remember those horrible, draining hours. They were a gap in her memory. When she tried to recall how she’d answered a particular question, her brain seized up and did not let her relive it.

She didn’t want to relive it. She never wanted to think about it again.

Seven days until the scores were out. Every booklet in the province had to be checked, double-checked, and triple-checked.

For Rin, those days were unbearable. She hardly slept. For the past two years she had filled her days with frantic studying. Now she had nothing to do—her future was out of her hands, and knowing that made her feel far worse.

She drove everyone else mad with her fretting. She made mistakes at the shop. She created a mess out of inventory. She snapped at Kesegi and fought with the Fangs more than she should have.

More than once she considered stealing another pack of opium and smoking it. She had heard of women in the village committing suicide by swallowing opium nuggets whole. In the dark hours of the night, she considered that, too.

Everything hung in suspended animation. She felt as if she were drifting, her whole existence reduced to a single score.

She thought about making contingency plans, preparations to escape the village in case she hadn’t tested out after all. But her mind refused to linger on the subject. She could not possibly conceive of life after the Keju because there might not be a life after the Keju.

Rin grew so desperate that for the first time in her life, she prayed.

The Fangs were far from religious. They visited the village temple sporadically at best, mostly to exchange packets of opium behind the golden altar.

They were hardly alone in their lack of religious devotion. Once the monastic orders had exerted even greater influence on the country than the Warlords did now, but then the Red Emperor had come crashing through the continent with his glorious quest for unification, leaving slaughtered monks and empty temples in his wake.

The monastic orders were gone now, but the gods remained: numerous deities that represented every category from sweeping themes of love and warfare to the mundane concerns of kitchens and households. Somewhere, those traditions were kept alive by devout worshippers who had gone into hiding, but most villagers in Tikany frequented the temples only out of ritualistic habit. No one truly believed—at least, no one who dared admit it. To the Nikara, gods were only relics of the past: subjects of myths and legends, but no more.

But Rin wasn’t taking any chances. She stole out of the shop early one afternoon and brought an offering of dumplings and stuffed lotus root to the plinths of the Four Gods.

The temple was very quiet. At midday, she was the only one inside. Four statues gazed mutely at her through their painted eyes. Rin hesitated before them. She was not entirely certain which one she ought to pray to.

She knew their names, of course—the White Tiger, the Black Tortoise, the Azure Dragon, and the Vermilion Bird. And she knew that they represented the four cardinal directions, but they formed only a small subset of the vast pantheon of deities that were worshipped in Nikan. This temple also bore shrines to smaller guardian gods, whose likenesses hung on scrolls draped over the walls.

So many gods. Which was the god of test scores? Which was the god of unmarried shopgirls who wished to stay that way?

She decided to simply pray to all of them.

“If you exist, if you’re up there, help me. Give me a way out of this shithole. Or if you can’t do that, give the import inspector a heart attack.”

She looked around the empty temple. What came next? She had always imagined that praying involved more than just speaking out loud. She spied several unused incense sticks lying by the altar. She lit the end of one of them by dipping it in the brazier, and then waved it experimentally in the air.

Was she supposed to hold the smoke to the gods? Or should she smoke the stick herself? She had just held the burned end to her nose when a temple custodian strode out from behind the altar.

They blinked at each other.

Slowly Rin removed the incense stick from her nostril.

“Hello,” she said. “I’m praying.”

“Please leave,” he said.

Exam results were to be posted at noon outside the examination hall.

Rin closed up shop early and went downtown with Tutor Feyrik half an hour in advance. A large crowd had already gathered around the post, so they found a shady corner a hundred meters away and waited.

So many people had accumulated by the hall that Rin couldn’t see when the scrolls were posted, but she knew because suddenly everyone was shouting, and the crowd was rushing forward, pressing Rin and Tutor Feyrik tightly into the fold.

Her heart beat so fast she could hardly breathe. She couldn’t see anything except the backs of the people before her. She thought she might vomit.

When they finally got to the front, it took Rin a long time to find her name. She scanned the lower half of the scroll, hardly daring to breathe. Surely she hadn’t scored well enough to make the top ten.

She didn’t see Fang Runin anywhere.

Only when she looked at Tutor Feyrik and saw that he was crying did she realize what had happened.

Her name was at the very top of the scroll. She hadn’t placed in the top ten. She’d placed at the top of the entire village. The entire province.

She had bribed a teacher. She had stolen opium. She had burned herself, lied to her foster parents, abandoned her responsibilities at the store, and broken a marriage deal.

And she was going to Sinegard.

CHAPTER 2

The last time Tikany had sent a student to Sinegard, the town magistrate threw a festival that lasted three days. Servants had passed baskets of red bean cakes and jugs of rice wine out in the streets. The scholar, the magistrate’s nephew, had set off for the capital to the cheers of intoxicated peasants.

This year, Tikany’s nobility felt reasonably embarrassed that an orphan shopgirl had snagged the only spot at Sinegard. Several anonymous inquiries were sent to the testing center. When Rin showed up at the town hall to enroll, she was detained for an hour while the proctors tried to extract a cheating confession from her.

“You’re right,” she said. “I got the answers from the exam administrator. I seduced him with my nubile young body. You caught me.”

The proctors didn’t believe a girl with no formal schooling could have passed the Keju.

She showed them her burn scars.

“I have nothing to tell you,” she said, “because I didn’t cheat. And you have no proof that I did. I studied for this exam. I mutilated myself. I read until my eyes burned. You can’t scare me into a confession, because I’m telling the truth.”

“Consider the consequences,” snapped the female proctor. “Do you understand how serious this is? We can void your score and have you jailed for what you’ve done. You’ll be dead before you’re done paying off your fines. But if you confess now, we can make this go away.”

“No, you consider the consequences,” Rin snapped. “If you decide my score is void, that means this simple shopgirl was clever enough to bypass your famous anticheating protocols. And that means you’re shit at your job. And I bet the magistrate will be just thrilled to let you take the blame for whatever cheating did or didn’t happen.”

A week later she was cleared of all charges. Officially, Tikany’s magistrate announced that the scores had been a “mistake.” He did not label Rin a cheater, but neither did he validate her score. The proctors asked Rin to keep her departure under wraps, threatening clumsily to detain her in Tikany if she did not comply.

Rin knew that was a bluff. Acceptance to Sinegard Academy was the equivalent of an imperial summons, and obstruction of any kind—even by provincial authorities—was tantamount to treason. That was why the Fangs, too, could not prevent her from leaving—no matter how badly they wanted to force her marriage.

Rin didn’t need validation from Tikany; not from its magistrate, not from the nobles. She was leaving, she had a way out, and that was all that mattered.