The Twelve-Mile Straight

Sara rolled her eyes, hiding her smile. She’d heard songs like it before. “Baby, that was delightful. You’re a regular Irving Berlin.”

“Who’s Irving Berlin?” Elma asked. Her mouth still burned with the grapefruit, with the acid shame of never having eaten grapefruit before. She wanted more, but she didn’t want to ask.

“Elma,” Sara said, taking both her shoulders in her hands, looking her deep in the eyes, “we’re going to teach you a thing or two.”

“Or three or four,” sang Jim on his banjo. “Or maybe more.”

When the doctor’s bill came, it came on a Sunday morning, when Dr. Rawls knew Juke would be in church. A colored boy on a borrowed bicycle pedaled barefoot all the way from Florence. He made sure Elma was the one to open it before she scurried back into the kitchen. Inside the envelope, tucked behind the bill, was a letter typed on onionskin paper. Nan stood with Wilson on her hip, watching her read it. It took a moment for Elma to see that it wasn’t Manford Rawls’s name on the letterhead but Dr. Oliver Rawls, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia.

“Atlanta,” Elma whispered, as though it were the name of a holy city. She thought of Josie Byrd’s spotless white shoes, the knee-high boots of the yellow-haired dog breeder.

Oliver Rawls was the youngest son of Manford Rawls. Elma remembered him vaguely. He was ahead of her in school, far enough that he was graduating from high school when she’d been learning arithmetic. Mostly she remembered his limp, first on crutches, then on a cane. A head of dark curls, and round eyeglasses like his father’s. Now he was a doctor like his father, a hematologist. He studied blood. He had heard about the twins from his father—“an exceptional case indeed.” Would Mrs. Jesup—he said Mrs.—consider bringing the children to his laboratory in Atlanta for a few tests? Nothing invasive—just some blood work. “Our blood reveals more about ourselves than you can imagine.”

Elma was leaning against the stove. When she’d finished reading the letter aloud, she dropped it to her side. “Blood work,” she spat. She felt sick. Then she raised the letter and read it once more, to herself. “No one’s gone stick those babies again,” she said, “not if I have any say.” But she kept her eyes on the page. “Some big-city scientist thinks he’s putting his hands on my babies?” She looked up, remembering Nan, remembering her father wasn’t in the room. “Our babies,” she said quietly.

Then her eyes found the note at the bottom of the page. “PS,” she read aloud. “I understand travel may be difficult. My father is willing to carry you to Atlanta, and I am willing to compensate you for your trouble.”

Elma lowered the letter again, this time creasing it a little in her fist. “Some big-city scientist thinks he can buy me like a hog?” She produced a laugh. “I’m fixing to burn this with the rest of the trash,” she said, but she put the letter in the pocket of her apron and kept it there, and spent the rest of the day singing a tune inside her closed mouth.

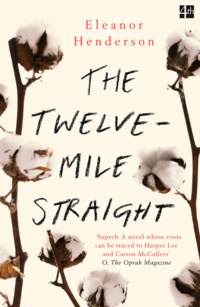

Sara and Jim were good hands. Juke taught them how to take the peanuts out of the ground, to thresh and stack them, to bale the hay. He taught them how to top and strip and cut the sorghum, and Nan and Elma helped to mill and cook and bottle it. When the cotton wanted picking, Sara and Jim made a game of it, racing to see how fast they could fill their bags, the way Elma and Nan had done when they were small. Their hats bobbed along the west field, Jim’s voice filling the air with songs of rabbit-tail cotton and candy-cloud cotton, cotton soft as a baby’s cheek. The other pickers stayed along the road, taking their midday meal under the lacy shade of the cottonwood tree, while Sara and Jim ate at the big house. They’d come back for harvest because they needed the work, Ezra and Long John and Al, and because Juke had been good to them. (Al’s wife had begged him not to return to the farm, and Al had said, “He all right. He won’t do me no harm,” and his wife said, “Just don’t be coming back to town dragged by no truck,” and kept all three sons at home and said if they even looked at a white girl she’d kill them herself.) They kept their eyes on the ground, away from Elma, away from Juke, away from the gourd tree, and they didn’t come near the house. At the cotton house, when it was time to weigh in at the end of the day, they didn’t meet the young couple’s eyes, but Jim tipped his hat as though he didn’t notice, and whistled, impressed, at the biggest pull. Usually it was Long John, but on a day when Long John didn’t come, it was Jim himself who picked two hundred and eighty pounds, more even than Juke, who was not shown up but proud. “They teach you to pick cotton in New Yawk, Jimbo?”

For supper there were boiled peanuts and greens and salt pork and beaten biscuits soaked in syrup, and Jim and Sara remarked over every bite, falling over themselves, and even Nan couldn’t hide how pleased she was. After the meal, the men would throw horseshoes in the scrubgrass yard while the women washed the dishes. Then Sara would bounce a baby on her knee while Jim played his banjo or guitar on the front porch, “Travelin’ Blues” and “Buffalo Blues” and “Boll Weevil,” and they’d all listen, shelling field peas while the sun went down. After a while, the music eased even Elma. The voice Jim used was his own. He sang and the dogs howled after him. When they howled too long, Juke threw the pea jackets at them, and they ate them up. One evening a chain gang limped up the Straight, their sweat-soaked handkerchiefs hanging like bright tails from their back pockets, and as they leveled the ditches Jim played them “Birmingham Jail,” and they sang along, and then, wanting to give them something brighter, he played “Ain’t Misbehavin’,” and they sang and danced too, even the shotgun guard Lloyd Crow, who was known to enjoy a pint of gin with Sheriff Cleave now and then, clapping his hands along to the music before moving the men on. Jim and Sara talked of their travels—speakeasies and soup kitchens, revivals and picture shows, the camps along the flooded Mississippi. Many nights they’d slept in their car at the edge of shantytowns, giving shelter to those who needed it. At marked houses, they begged for food; at farms they worked for milk and eggs; they stayed put until they had enough to buy or trade for gasoline; then they kept going. For a while Jim had run rum in Philadelphia, but he got into some trouble and they went south. They’d been traveling for three years. Now they were twenty-three, and Sara wanted a baby.

“I can’t stand it one more minute,” she said, taking Winna Jean into her lap. “I’ve got to have one.”

“Another mouth to feed,” Jim said. “No, thank you.”

Sara blew a raspberry on Winna’s cheek. “Babies eat nothing but momma’s milk. Look at this momma! She’s got two and they’re still fat as can be.”

“They don’t drink milk forever, darling.”

“Well, by the time they’re through, times will be better.”

Juke laughed from his rocking chair, sending shreds of tobacco flying from his mouth. “Maybe in New York they will. In Georgia, times is always lean.”

“We never have missed a meal,” said Elma, not looking up from the peas.

Juke said, “They’re a blessing, no matter how lean the times.”

Harvest went on. In the evening, there was celebration, but in the daylight hours, the fields had a way of keeping your mind on the ground. The seeds grew, no matter what was happening in the big house. They managed to keep the weevil away, but that year there were army worms. If you sat dead quiet on the porch, you could hear the shush of their chewing through the fields. Juke used all of Elma’s good flour to make an arsenic paste, and early one morning while the dew was still on the cotton he and Jim crept into the field and lay the poison down. Then when you sat on the porch the only sounds were the cricket frogs and your own lonesome breath.

For a time it seemed that a new season had come. The floorboards were cool in the morning. The gnats were gone. In the yard, the guineas squawked; the one Elma had named Herbert did his rain dance. All year long they’d prayed for rain along with him, but at picking time, they prayed it stayed away, at least until they’d plucked all the cotton from the fields. The second week of October, though, brought a steady storm, not strong enough to lay the cotton flat, but long enough to keep them indoors for three days. When the rain stopped, they’d have to rush to empty the west field of cotton, if it wasn’t ruined already. For now, there was nothing to do but stay indoors. While Winna and Wilson took their morning nap and Nan started on the churning, Elma packed a basket with hoecakes and dashed through the rain to Sara and Jim’s shack. Juke and Jim were out at the still, and Sara was sewing something she held behind her back while she opened the door.

“I brought dinner,” said Elma, shaking the rain out of her hair.

“Aren’t you sweet,” Sara said. She held up her sewing: a doll. “You caught me. It’s for Winna Jean.”

Elma took it from her. “Ain’t you sweet!” She couldn’t help it. It was no guano sack rag baby. It was made with what looked like flax cloth, and it was wearing a yellow rose-print dress with a flax cloth apron and black felt Mary Jane shoes.

“It’s not finished,” Sara said, taking it back. “She’s got to have button eyes.”

“She’s pretty as a picture,” Elma said.

“Well, I’ll tell you the secret. It’s the cotton she’s stuffed with. Finest cotton in all of Georgia, from what I hear.”

“Oh, yes! I bet it is.”

“Your daddy won’t mind I took some?”

Elma waved her hand. “Daddy’s got so much cotton he won’t miss a doll’s worth.”

“But it’s not his, exactly, is it?” Sara placed the doll against her pillow and sat down beside it on the cot, and Elma put the basket on the table.

“Might as well be. It’s George Wilson’s field, but he ain’t set foot in it but once a season.”

Sara nodded knowingly. “He doesn’t want to get dung on his trousers.”

“Fine by me. Better than coming over every day to complain about this or that. The Cousins, down the road? They don’t have barely a minute of peace. They all live in shacks, a whole mess of kin on that farm. The planter, he’s brother to one of the wives, he’s always out on the porch of his house pointing his finger, saying do this or do that, and in what order. He once made little Lucy Cousins take out all the stitches in his socks and put them back again. Least Mr. Wilson stays out of the way.”

She didn’t say that he’d stayed away for some time, that he and her daddy had fallen out. When the weevil came and so much cotton was lost, when he seemed to be one of only a few landowners with any money left, George Wilson had bought up farm after farm. Before long, he didn’t have time for the crossroads. When there was business to be done, Juke had gone into town, to visit with him at the mill. And then the babies were born, and Genus was killed, and as far as Elma could tell, her father stopped going to the mill at all. She had seen nothing of the Wilsons.

“You like that,” said Sara. “For people to stay out of your way.”

“Not you!”

“Well, maybe that’s because I haven’t asked you about the twins yet.”

Elma sat down in one of the wooden chairs. Then, remembering for the first time where she was, she stood up again. She could still smell the smoky char of the fire that had nearly burned the shack down. “What about them?”

“How they look so different. I mean—”

“I know they look different,” Elma said sharply. She busied her hands in the basket. Then, more gently, feeling her tongue go loose, she said, “I didn’t ask for two babies.” She had thought that sentence hour after hour, it had lived silent in her head, and there it was now, out on the table. She laid the hoecakes side by side. They were heavy as rocks, made with the low-grade flour left in the back of the pantry, and Elma wished she’d made something else instead. “They have two different daddies, is how come. They’re twins, grown up inside me at the same time, but they ain’t all the way kin.”

“That’s something,” Sara said, wide-eyed.

“Alls I’ll say,” Elma said, but she’d already said more than she ever had, even more than she’d said to the newspaperman—when had she ever had a real friend to talk to, who could talk back!—“Alls I’ll say is one of the daddies is Freddie Wilson. The landlord’s his granddaddy. More like a daddy.”

“The one that owns the farm?”

“He ain’t no more than a dog. Freddie, that is. Granddaddy too, I reckon. Folks look down they noses at the baby for his skin, well! The Wilsons ain’t no better! They don’t even take up for they own.”

“You sure these Wilsons don’t have mulatto blood, and that’s how come Wilson’s dark? It’s the uppity white folks, the ones with the slaves in the family—”

“Oh, no!” Elma shook her head. “Not the Wilsons. They’re pure as cotton. No. No. They’re two daddies. That’s alls I’ll say. Nature has its own ideas, I reckon.”

“I reckon it does,” Sara said, trying on the word.

“You think a mare ever thought she could mate with a donkey?”

Sara considered it. “I reckon she mates with whoever she pleases.”

“Well, the first mare that gave birth to a mule ought to have been as surprised as me. But you think she’d have loved him any more if he’d been a horse?”

“I reckon not.”

“They’re both gone now, the daddies. One is dead and one might as well be.” Elma fingered the envelope in the pocket of her apron. “That’s alls I’m like to say about that.”

Sara crossed the room and touched her hand to Elma’s shoulder. “Thank you for the lunch.” She took a hoecake from the table. They both took bites. The rain tapped against the tar paper roof.

“You ain’t spent much time near livestock,” Elma asked her, “have you?”

“Can’t say I have.”

“A mare don’t mate with whoever she pleases. She mates with whatever ass is penned in with her.”

Sara laughed. Before she could stop herself, Elma asked, “How do you keep from getting caught?”

“Do what?”

“From getting pregnant.”

Sara didn’t flinch. “You ain’t spent much time near Catholics, have you?”

“Can’t say I have.”

“You know your time of the month, don’t you?”

“I don’t bleed anymore, not while my milk is in.”

“Well, you count it. Just before or just after your time is the safest. It’s the time in the middle you worry about.”

Elma nodded, though she didn’t quite understand.

“Good thing about my time of the month is that it’s my time, not Jim’s. He might be the one getting caught, come Christmas.”

Now Elma laughed. She smoothed her apron. “A letter came from Atlanta.” She slipped it out of her pocket. “Some doctor at Emory University wants to study on the babies.”

“Study on them? What for?” Sara reached for the letter and lowered herself into a chair.

“He wants to see how come twins can have two daddies, I guess. I ain’t gone let him, though.”

“Why not?” Sara didn’t look up from the letter.

Elma sat on her hands. Could doctors really tell if two babies were twins? Could they even tell if they were brother and sister? She said, “I don’t want my babies poked and prodded. I don’t want them in a medical journal. They ain’t specimens!”

“But he says he’ll pay. Times are hard!”

“How do I know he’ll pay? How do I know I won’t get there and they’ll take the babies away?”

Sara snorted. “Elma, Emory University is a respectable institution. They’re not going to take your babies. Tell them your terms.”

Elma shivered at the word. Her “terms.” Yes, she had set terms before—she had set terms with her father. That was the word for it, wasn’t it?

“Tell them what you demand in order to cooperate with their study. Atlanta’s all the go! Have you ever been?”

Elma shook her head.

“Well, it’s bigger than a bread basket, let me tell you. The men aren’t bad to look at, either. Oh, you’re going to love it! You can take our electric!”

“I don’t know how to drive. Well, I know a little.”

“I’ll teach you!”

“Sara, I can’t. I’m much obliged, but I can’t leave. Daddy would never let me, for one.”

“He sure keeps you down on the farm, doesn’t he?”

Elma took another bite. For a moment a dry cake of panic lodged in her throat. What did Sara know about her father? About Nan? Was Elma the last person to know what was happening in her own house?

“I don’t mean nothing by it,” Sara said.

Elma could see that she didn’t. She swallowed. The rain was lightening up on the roof. She had a flash of herself, like a remembered dream, flying through Atlanta on a streetcar, holding her hat tight to her head. If her father could leave the farm, if her father could go to the city and be someone else, why couldn’t she? She had told him her terms before. She would set her own terms now.

She said, “How’d you get your hands on that electric, anyway?”

Sara smiled around a mouthful. “You can get your hands on just about anything if you’re clever enough.”

“You stole it?”

“It’s on loan from my uncle up in Buffalo. He used to like to kiss me with his tongue. I figure he had it coming. First he lost the car, then he lost everything else in the crash.”

Now the hoecake sat like a stone in Elma’s stomach. To Nan, her father used to call himself that, an uncle, just like she’d called Nan’s father Uncle Sterling. “Come on and hug Uncle Juke’s neck. Come on and give Uncle Juke some sugar.” Then he stopped. Was that when it had started up, with Nan?

Her mind fell upon something. She closed her eyes and followed the branches of the tree. If her daddy was Wilson’s daddy, then Wilson was not Winna’s brother but her uncle. The only person he was brother to was Elma.

So if the doctors discovered the babies were kin, well, that was because they were.

Sara was still talking about the car. “Wasn’t all I took. All that good cloth doesn’t come cheap.”

Elma sat up. “You stole that too?”

“Do you know how much the dress factory pays? I prefer to call it ‘souvenir harvesting.’”

“Harvesting!” Elma swatted Sara’s arm. “Well, lucky for us, we got nothing for you to harvest. Nothing but a handful of cotton.”

“Just watch out. I might take me a souvenir baby.”

Elma laughed. Her ears listened for the babies, but all she heard was rain. She knew she should go to them, but she felt frozen in place. Nan was there. Her father wasn’t. Let Nan listen for them. That was what Nan wanted, wasn’t it? Same as Elma. To be mothers to their children. To share them, even! But to be mothers with their whole selves, not to be split into fractions. She allowed herself to imagine it: Nan and Elma living in the big house with Wilson and Winna. Her father gone from the farm. Not gone from the world, like Genus. Just disappeared, like Freddie. Gone! Sara would be there too. In the shack, making dolls for the babies. After doing the doctor’s study in Atlanta, maybe they’d have a little money to live on.

Then, still laughing, she felt the air go out of her lungs. She looked sideways at Sara, thinking how strange it was that you never really knew anyone, that no matter how much your heart warmed to a stranger, she’d always be a stranger to you. She caught her breath. She was dizzy with fear and envy, certain of some unavoidable loss. It wasn’t just her children she feared losing. Harvest was nearly over. Sara and Jim never stayed anywhere long. Soon they’d be gone, their automobile with them.

After their meal, when the rain had quieted to a lazy drizzle, Sara and Elma raised the windows and hung their heads outside. The guineas had come out again, honking nervously through the yard, through the coal black ash of the old shack they liked to nest in. High above the sorghum, a purple martin emerged from a gourd. “That’s a funny scarecrow,” Sara said, pointing. “Instead of scaring the birds away, it gives them shelter.”

“We like those birds,” said Elma. “They catch the skeeters.”

“I’ll tell you something, Elma. They do no such thing.”

Elma studied the gourd tree. Someone—her father?—had removed the length of rope, or it had been blown down in the storm. Looking at it with Sara beside her, it was almost just a gourd tree. “Maybe it’s an old wives’ tale.”

“You Southerners have peculiar ways of keeping some in and others out.”

A lock of Elma’s hair had fallen. She took a pin from her bun and then stabbed it back. “Do we now.”

“It would be one thing,” said Sara, “if it worked.”

TEN

NINE TIMES OUT OF TEN IT WAS WOMEN WHO GOT HIM INTO trouble. He had red blood coursing through him like any man.

But the day Juke met the girl who would be his wife, it was String he had his mind set on seeing. He’d been sent by his daddy to the feed and seed in town, and he took their john mule, Lefty. They had a barn full of mules then, mostly spritely young mollys who could plow in their sleep, but Lefty was the only john, and Juke’s favorite. He was near big as a horse and spotted black on white clear through his mane. He’d been George Wilson’s favorite too. It had been George who’d finally taught him to turn right.

It was 1901, just after the Wilsons had built the mill and moved from the farm into town. George Wilson and his brothers had inherited a hill of money from an uncle in the railroad business. In a few years George had grown bored of planting, of buying up land all over Cotton County. He got it into his head to buy rights to the Creek River at the edge of town, where the river and the Straight and the new railroad converged. He borrowed more money from his brothers in north Georgia, one in the turpentine business, another in sawmills. He found builders and then mill hands in the same way, by riding his horse from farm to farm. He needed Juke and Juke’s father at the crossroads farm, but he pulled whole families from cropper cabins five counties around. On the train from Marietta, George’s brother sent cars full of farmers’ daughters in search of work. He sent the sheriff around to the Fourth Quarter to find loose-foot Negroes. The sheriff offered them the chain gang or the picker room. They chose the picker room. All of Florence was mighty proud of that mill.

Juke wanted to see it himself. So, after fetching the three sacks of corn seed, he tied the mule and its cart to a gum tree by the road and walked down to the river to wait for String to walk home from school. It was springtime, the wiregrass along the river wild with cornflower. Juke kicked off his shoes to chase tadpoles. When String came along the railroad and saw him, he let out a yelp of joy. “What in Hades you doing out here?”

The Wilsons’ new house was the biggest house Juke had ever gotten close to, with a porch that wrapped around three sides. From the front porch you could see the cotton mill straight down the hill, three stories of bricks and as long as a freight train. The Creek River rushed rapid out of the woods there, feeding into the new dam that formed a pond at the head of the mill. To the east you could see the three-acre garden Parthenia Wilson had planted for the mill families, and Lefty, still tied to the tree by the Straight. To the west you could see the mill village, where the mill families lived, just a dozen clapboard bungalows then and more rising before Juke’s eyes, houses no bigger than the shacks on the farm, the spaces between them no bigger than each house. And the Wilsons owned all of it. At ten years old, John Jesup—he was not yet called Juke—had traveled no farther than Macon, hopping the freight train with String and his cousins, and that city, with its smokestacks and street trolleys and brick-paved block after block, had left him feeling nauseous with longing and homesickness and the penny candy String’s cousins had stolen from the sweets shop, though they had plenty of pennies in their pockets. There was so much to see he’d had to close his eyes.