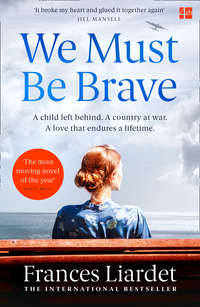

We Must Be Brave

Shouting at the candle man.

‘Did you stay in the hotel just one night, darling?’

‘That’s what you do in hotels.’ She explained it to me. ‘You stay all night. They give you soft pillows. We took the pillows to the cellar when the raid started. I was comfy in the cellar but Mummy wasn’t.’

Her voice was so clear.

‘You don’t know what the hotel was called?’

‘No. But Mummy can tell you when she comes.’

I leaned back on my heels. ‘I thought we’d go and visit those bus ladies. They’re staying in an interesting house called Upton Hall. They have an enormous vegetable plot.’

Pamela looked unconvinced.

‘And a suit of armour. Like knights wear.’

That was more like it.

She had no coat, so I got a clean flour sack and pulled holes in the seams for head and arms. It did very well. I lifted her onto the bicycle rack and she clung to the saddle, face set.

‘Is it all right, Pamela?’

‘The bicycle is digging my bottom.’

I lifted her down again, glancing somewhat shamefully at the rack. No one could sit on those black bars. I went and got my old sheepskin from where it lay, somewhat yellowed, on the bedroom floor by my dressing table. Rolled up and tied tightly, it was perfect padding. Pamela screamed with delight as I pushed down hard on the pedal and we sailed off.

‘Ow, ow! You’re sitting on my fingers!’

‘Hold my waist, like I said. Arms round my middle.’

Selwyn’s fog had cleared and the sky was a pale, uncertain blue marked across with high, motionless bars of pearl-grey cloud. I heard a tinny rattle. ‘Take your feet away from the wheels, Pamela Pickering.’

‘How did you know my name?’

‘Mummy wrote it in your clothes.’

‘Well I never.’ She gave a breathless, adult little laugh.

We crossed the main road. The lane wound on, ruttier now. She was lighter than a quarter of grain, if more mobile. The hedges grew higher: nobody had cut them, and soon they’d be as tall as they had been when I was a child, and walked these lanes alone with one wet foot, my left foot. ‘I had a hole in my shoe when I was young, you know.’

‘Didn’t your mummy mend it?’

‘She didn’t know how.’

We came to the Absaloms. A row of cottages sunk into the damp of the lane. Mother and I had lived at Number One. It was derelict now, and should have no power to hurt me, but I never came by here if I could help it. Only today, with the child, because it was the quickest route to the Hall. ‘See those walls? They’re called the Absaloms. They were cottages once. I used to live in the end one.’

‘It’s got no roof!’

‘It did have. The others didn’t. They were already ruins.’

‘Can we play in those ruins?’ Pamela said.

‘Not today.’

I dismounted at the beginning of the drive to the Hall. The potholes were now deadly. It was hard skirting them with Pamela on the back of the bicycle. I whistled under the trees to keep our spirits up, and eventually we reached the old dairy which was alive with the chip of metal on stone.

‘Hello, young’un,’ said a familiar sunburnt face of forty or thereabouts, quizzing us through a rough new gap in the bricks. It was William Kennet, who gardened for Lady Brock. When he wasn’t turning over the grounds to food crops he was busy with Home Guard duties – in this case, fitting the old dairy out with gunsights. So many things, these days, had to be seen to be believed.

‘Morning, Ellen,’ he said. ‘Who’ve you got there?’

‘Morning, Mr Kennet. Sergeant Kennet, I beg your pardon. This is a little girl from Southampton.’ I spoke meaningfully, and he gave a slow nod. ‘Say hello, Pamela!’ I used my brightest tone.

Pamela waved from her perch but said nothing. Her face was pinched. I was hungry, so I knew she must be too.

‘What are you doing?’ she asked William.

‘Giving this old wall a few holes,’ he told her. ‘To make a nice breeze in the dairy.’

‘It must be awfully difficult with that bad hand.’

‘Oh Pamela, that’s not polite.’

William smiled, held out the hand to her. ‘Look, it holds a chisel right well. So I can hammer away with my hammer.’ He made a claw, to show her. His thumb and finger were huge beside hers, calloused and bent from overuse. Behind the finger was a single nub of a third finger, and then nothing. What remained of the palm and back of the hand was bound by scar tissue, now silvered and braided. It was a creation of a shell, during the Great War, at the Battle of Messines. He was a copper-beater before that shell screeched over, a high craftsman, but I never knew him as such. To me he was a gardener, with a potting shed that was a refuge throughout my later childhood, a charcoal stove that was the only warm thing in my life.

Pamela, awed, was mimicking him, trying to make her own claw, her small perfect little forefinger sliding off the soft top of her thumb. ‘Mummy’s still in Southampton,’ she confided to him. ‘But she’s coming to fetch me this afternoon. Do you know, we saw a house with no roof!’

‘Did you now?’ He raised his eyebrows at her. ‘That’s not a lot of use, is it? A house with no roof. Now, Upton Hall certainly has a roof, and a tower too. Wait till you see it.’ He glanced at the bicycle. ‘I’m glad you found a use for that old sheepskin.’

‘It’s not old. It’s lovely. I used to sleep on it when I was tiny.’

‘I know.’ He gave me his square grin. ‘It was me that gave it you, when you were newborn.’

‘Oh, William, how very kind!’ I was astonished. ‘I never knew! I would have thanked you for it long since!’

He shrugged, still smiling. ‘It was a cold winter, and I had it to spare. And your ma and pa thanked me on your behalf, very civilly.’

‘I keep forgetting that you worked for my father.’

‘You were too young to remember. And I wouldn’t call it work. More like a day here and there.’ Mr Kennet tipped his hat with the remains of his right hand. ‘Now, I can’t linger, my dear. Come and have a cuppa when you get time.’

‘I’ll try,’ I said, wondering when I would ever get time.

Lady Brock opened her front door, boots spattered and mackintosh hemmed with mud.

‘Good morning, Ellen. How do you like our defences? Have a care, William Kennet will soon be asking you for the password of the day.’ She came down the steps. ‘I saw you, skirting the quagmires. Sometimes I’m glad Michael’s no longer with us, you know. He wouldn’t have minded the ploughing –’ she indicated, with a wide sweep of her arm, the great pathwayed allotment of ragged, nutritious brassicas and rich, black potato furrows which had replaced her lawns and rose garden ‘– but he’d have loathed the drive. We only needed a few ruts for him to say it looked like bloody St Eloi.’ She turned to Pamela. ‘I do beg your pardon, dear, for my foul language.’

After the Great War Lady Brock’s husband, Sir Michael, had been an ambulant if rather wheezy hero; over the next twenty years the gas had reduced him by increments to a gurgling wraith in a bath chair before killing him in September 1939, ten days into the present war. Lady Brock as usual had a gorgeous rich red on her wide, rather fish-like mouth. The lipstick, plus a feathered hat and a shy, rarely seen beast of a fur coat, constituted all she had of glamour. On the day of Sir Michael’s death, which had been by internal drowning, she had donned them all, to serve as her breastplate, sword and buckler.

Pamela gave her a guarded look. Lady Brock laughed.

‘We’ve come to speak to two of the women who were on the bus,’ I said.

‘Ah. I know the ones you mean. I’m afraid they’ve all gone. They departed en masse at first light, desperate to get home. Like a shoal of salmon. There was nothing I could do to stop them.’ She saw my shoulders sag. ‘Buck up, dear. All is not lost.’ She crouched down in front of Pamela. ‘So you came by bicycle!’

Pamela nodded.

‘Was it your first time?’

Pamela nodded again.

‘That deserves an egg, at the very least,’ said Lady Brock, ‘if not some mashed potato.’

She cooked without removing her mackintosh, flinging cold mashed potato into the sputtering frying pan along with the egg, stabbing unhandily at the mixture with the tip of a long iron spoon. ‘I shan’t disturb Mrs Hicks. She went to see her sister in Cosham and got stuck on a train all night. Caught her absolute death.’ When Pamela was served she picked up a pan containing the remains of a burnt breakfast of porridge. ‘The girls scorched this specially. Come with me, Ellen, while I feed Nipper.’

We stepped outside into the flagstoned yard. Lady Brock scraped the porridge pan into a tin bowl and the dog, a rangy collie with one blue eye, loped out from the empty stables. Upton Hall currently housed Nipper, Mrs Hicks, William Kennet, six land girls and Lady Brock herself. The herds were dispatched, the fields turned to wheat and turnips. ‘I had two hunters in those stables, and now that dog’s the only resident,’ she remarked now, quite cheerfully. ‘I don’t know. What a bloody comedown.’

She knew what had happened to Pamela. The two women on the bus had told her.

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘Anyway, Pamela doesn’t know which hotel it was. My guests thought it might have been the Crown. The family’s from Plymouth, so they’d have stayed in an hotel.’

Lady Brock banged the spoon in the pan to release the last scraps of porridge and the dog snapped at them as they fell. ‘It was the Crown Hotel. The ladies told me.’

‘Ah. Well.’ I ran my toe along the gap between two flagstones. There was something comforting about the worn edges. ‘I’ll telephone the Crown, then, and the police if need be. And Mrs Pickering, who couldn’t be bothered to mind her own child, will come with tears of joy to us.’

Lady Brock surveyed me, a gentle pike.

‘That was uncharitable of me.’ I felt the blush heat my cheeks. ‘My people were noisy last night.’

‘I didn’t hear mine. I put them in the drawing room and took a spoon of Michael’s mixture.’ Lady Brock’s eyes glinted. ‘Don’t breathe a word to Dr Bell but I’ve got some left over. It’s absolutely topping. One doesn’t move a muscle all night. Now, let’s go. Pamela’s scraping the pattern off that plate.’

Pamela and I followed Lady Brock past the ballroom. The chandeliers hung sheeted in canvas from the dim ceiling; the alabaster lions were corralled in some hidden basement, the carpets rolled up and gone. Instead there were a half-dozen rows of trestles bearing camouflage netting for the anti-aircraft batteries. Many of us in Upton came here to weave strips of drab fabric in and out through the mesh of tarred ropes. Our first efforts were returned as ‘insufficiently garnished’ or, as William put it when he saw them, ‘like a pack of dogs with mange. Jerry will see right through ’em and let fly.’ So now we worked until the sides of our hands were rough and sore. Today the room was empty, the half-finished nets hanging forlorn.

‘Aren’t those holey tents,’ Pamela said.

‘Yes. They need mending.’

We mounted the stairs. The suit of armour glimmered in the darkness of the upper corridor next to the door of Sir Michael Brock’s bedroom, the gloom now permanent with the blackout. In former days it stood in the hall, lit around with candles so that its reflection hung, an inverted ghost in the depths of the polished oak floorboards. Candles but no candle man, no candle men here. Lady Brock had been faithful. What kind of a woman comported herself in that way, shouting at a man all night with her child in the room? Too busy to notice when her curious little girl crept off outside? The floorboards were dried out and dusty now, the armour tarnished. ‘Mrs Hicks wants to get up here and apply elbow grease,’ said Lady Brock. ‘But I’m not having it. We both need to conserve our strength. Who knows how long this is going to last?’

I helped Pamela onto a stool. She lifted the visor and replaced it, transfixed by the grille, the blackness behind, the small creak as it settled into position. ‘Peep-bo,’ she said softly. ‘Peep-bo.’

‘I’ve always felt guilty about you, Ellen.’ Lady Brock’s voice, unused to speaking low, was husky. ‘I felt we didn’t do enough.’

Creak. Peep-bo. I remembered the grate at the Absaloms, black with past coal but no coal in it to burn, the cold looming from the walls.

‘It was very difficult to do anything for my mother,’ I managed to say at last. ‘She wouldn’t be helped.’

We left Lady Brock at her front door and went down the steps. ‘Perhaps my boys could buff up these floorboards for you,’ I said, as I helped Pamela onto the bicycle. ‘They’re always on the lookout for a job.’ I was exaggerating the case somewhat, but they were helpful boys on the whole, not overly given to skulking.

She stared out over my head, at the turned earth of the potato beds and the mud of her drive. ‘I’ll be down there with William, you know,’ she said. ‘In the old dairy. With my rabbit gun.’

‘And I hope that William would send you straight back again, Lady Brock. We need you.’

‘Not before I pot one for Michael.’ She narrowed her eyes. ‘I promised him, you see.’

We went home, pushing the bicycle through the kitchen garden and out through the back gate. The sky was the same light blue. I let Pamela chatter on, about the bicycle spokes, the brick wall, the crows in their high nests.

Selwyn opened the front door as we came up the path. ‘Give Pamela to Elizabeth,’ he murmured. ‘Let her go in.’

‘What news? Selwyn? Have you found Mrs Pickering?’

Pamela slipped past him into the house. Perhaps Mrs Pickering had come to the village hall. Perhaps she was even now indoors. Yes. Selwyn had let her in for Pamela to find, as a surprise. My heart battered my chest.

‘In a manner of speaking.’ He ran his hand over his eyes. ‘The Crown was bombed last night.’

4

‘WE CAN’T BE EXPECTED to behave as if we’re made of Derbyshire peakstone.’ Selwyn wielded his handkerchief. ‘That poor little child.’

The woman’s face was untouched, he told me. Her ration book was in her handbag, in the name of one Amelia Pickering, residing at the same Plymouth address she had sewn into her child’s clothes. ‘I called Waltham police station after you left,’ he went on. ‘Sit down, darling.’

I did so, and so did he. We faced each other in our sitting room’s comfortable armchairs. The lower part of my face, my cheeks, felt strange; the skin numb, tingling.

‘They managed to get through to Southampton. Then Southampton called them back about an hour ago.’ He blew his nose. ‘Mrs Pickering contacted them when Pamela disappeared, but they couldn’t get to the hotel until this morning. By which time it had been hit.’ A hollow, wooden rumble came from the kitchen, followed by a scream of pleasure. ‘What on earth is that?’

I cocked my head. ‘I think it’s Lord Plumer.’

Lord Plumer was an ancient croquet ball, legendarily unbeatable, named by Selwyn’s uncle after the general who, in turning the course of the Battle of Messines, had, in his estimation, spared the life of his nephew. Old Mr Parr, bereaved of both his sons at the Somme, had been grateful for small mercies. When he gave up croquet he had planed a flat underside onto Lord Plumer, fastened a lead plate thereto, and used it as a doorstop for the pantry. No one else was allowed to win a game with Lord Plumer.

The rumble returned. ‘That’s the way!’ we heard Elizabeth say, in a high, breaking voice. ‘Off it goes.’

‘You’ve told Elizabeth, then.’

‘Yes. She’s taking it badly.’ He spread his hands, clasped them as if washing. ‘Apparently Mrs Pickering called the police and then ran out to look for Pamela, only coming back at nightfall. And then, along with a dozen other unfortunates, she placed too much faith in the cellar. The ceiling came down on them all.’

I pictured her returning tear-stained in the evening to her certain death. For even while she was running in the streets, shrieking Pamela, Pamela, the bomb for the Crown was being loaded into its bay.

‘God damn them.’ I swallowed the stone in my throat. ‘I wish them eternal perdition.’

Selwyn breathed in. ‘That attitude helps no one, darling.’

‘It helps me.’ I swallowed again. ‘The police will come now, won’t they? And take her away?’

‘They will. Eventually.’ He took out his spectacles and started cleaning them. He was going to read the Bible: he always gave the lenses fastidious attention before doing so. ‘They’re looking for her father, obviously, and other relatives. They’ll be in touch soon.’

I pushed away a lock of hair. The bicycle ride had made it messy. ‘You could try the Book of Job,’ I told Selwyn. ‘We need his God now. One who can shut the sea with doors. Unload granaries of hail.’

Pamela was sitting on the kitchen floor, wrapping the croquet ball in a tea towel. Elizabeth was putting onions in a baking dish.

‘Baked onions,’ I said. ‘They take me back. Do you know how lucky we are, to have got all that precious onion seed from Upton Hall? Most people’s mouths are watering for onions. They haven’t seen one in months and months.’ I babbled on, in the same bright tone. ‘Months and months.’ Elizabeth’s eyes were brimming. I made to embrace her, my hands on her shoulders, but she shrugged me away.

‘No, Mrs Parr,’ she murmured. ‘It’ll only start me again.’

‘Dolly needs a headscarf.’ Pamela held up her swaddled ball. ‘Otherwise she might get earache in the wind. Do you know what happens then? Somebody irons your ear.’

‘No!’ I feigned amazement while Elizabeth dashed her tears away. ‘With a hot iron?’

Pamela sucked her teeth. ‘They put a towel over your ear first. And then they put the iron on the towel, and it’s so lovely and warm. Mummy’s being very slow.’

‘Yes, Pamela. She must be very busy.’

Elizabeth put the dish in the oven. ‘Perhaps she’s gone to see your auntie. Have you got any aunties?’

Pamela’s face puckered. ‘Why would she go and see Aunt Margie without me?’

‘You’re right,’ I said. ‘Of course she wouldn’t do that.’

‘Aunt Margie’s a long way away. She’s in Cape Town. They have grapes there and lots of flowers. I haven’t been there but Mummy went before I was born. She says it’s wizard. She wouldn’t go and visit Aunt Margie without me.’ She hummed a little and unwrapped the ball to fold the tea towel into an uneven triangle. ‘Bad headscarf.’

‘Let me.’ I took the tea towel and made a neater job of it, and knotted it as best I could under Lord Plumer’s flat chin.

Pamela cradled the ball experimentally, in each elbow, and then set it on the floor to take bobbing steps. ‘Pamela, we’re going shopping. Oh, do come on, darling. Do hurry up. Honestly, it’s like wading through treacle.’

I set three places at the kitchen table. Selwyn didn’t have lunch. Elizabeth started the last loaf, cutting it fine. We listened to the voice of a dead woman piped through Pamela’s mouth, Mrs Pickering exhorting her small child, and prepared the meal.

In the afternoon I found an old bed-jacket that my mother used to wear when she sat up against the pillows to drink her tea. It was a flouncy woollen affair with a flapping collar and silky straps, and it hung down almost to Pamela’s knees. When I drew it off her shoulders she clutched at the swathes of wool. ‘No. No, it’s too cosy. Let me keep it.’

‘You shall have it back when I’ve taken off these silly straps. We need buttons, nice big ones …’

I had no buttons large enough. After a long search we found, in a wooden box in the dressing room, the toggles from an old duffel coat belonging to my brother Edward. That coat had been so torn and stained that Mother and I had cut it into strips and burned it on the fire. I refused to worry about Edward because he’d told me, the day he left to go to sea, that I should never worry, that worry brought bad luck and he would always need luck. He’d been fourteen, I eleven, and since then we had spent a total of nineteen precious days together. His last letter, dated a month ago and headed Singapore, said I’ll take my chances here, drst Ell. The company is doing terrifically, what with soldiery everywhere. I’ve been in a few jams before now and know my way around. Place like a fortress – indeed, it is a fortress and always has been. I’ve been contemplating calling myself Senhor de Souza and speaking entirely in pidgin. But like as not will end up doing my bit.

At least doing his bit wouldn’t put his life in danger, not in Singapore. I was glad he was far away from all this.

Pamela was delighted with the toggles. They were of such smooth, dark-polished wood. I took her to the mill where she sat on the office floor while I tidied my desk. My eyes lit upon an advisory leaflet on the turnip gall weevil which for some reason had come my way, and which I was going to pass to Lady Brock, with her great root crop. It seemed now that this message, arriving as it did before the bombing, belonged to another world. Pamela sat leaning against the wall, sucking her thumb, putting two fingers over her eyelids to pin them closed. That seemed to comfort her, as did the battering of my typewriter keys when I began my letters. ‘Do more,’ she said, whenever I paused. ‘Keep going bangbang.’ It was a noisy behemoth of a machine. We went back to the house an hour before dusk and saw a policeman ahead of us, wheeling his bicycle up the path.

He turned to face us. The strap of his helmet ran beneath a chin now blue with the bristle that accumulated by the evening.

‘Mrs Parr,’ he said, by way of greeting. ‘I’m Constable Flack. Suky Fitch’s brother.’

‘Suky’s brother!’ Astonishing, how such a bulky individual could spring from the same stock as our diminutive mill forewoman.

The constable’s flinty, fifty-year-old eyes warmed. ‘We had different mams.’

He removed his helmet. For a sickening moment I thought he was about to announce Mrs Pickering’s death. But instead he said gravely to Pamela, ‘Would you be so kind, miss, and take this hat for me? I’ve got a great bag of papers to carry.’

He and Pamela went into the sitting room. Elizabeth was shutting up the hens, so I made tea the colour of washing water and took it through. ‘That’s my number,’ he was saying to Pamela. ‘And that there, GR, what do you think that means?’

‘It means you’re fierce. Grrr. So have you been to see Mummy?’

He lifted his bewildered face to me. I heard Elizabeth open the back door. ‘Pamela, I need to speak to the constable. Elizabeth’s got some milk for you.’

She burst out with a loud bellow. ‘Why won’t anyone bring me my mummy!’ I embraced her but she growled and with surprising strength pushed me away. ‘Don’t keep hugging me! You’re not my mummy!’ She stamped her foot. ‘Where’s my mummy!’ Her face crimson, she threw herself on the floor, roaring, ‘Mummy! Mummy! Oh, my mummy!’

Elizabeth came in. We gave each other blank, drained stares. The constable shifted in his chair. ‘I’ve got to get back before dark,’ he said through the din.

‘Come into the kitchen, Constable.’

We left Elizabeth kneeling beside the screaming child. As the door closed I saw her place the flat of one gentle hand on Pamela’s stomach. Her face, Elizabeth’s face, was a mask of sorrow.

In the kitchen Constable Flack handed me a child’s ration book. ‘This was found in her mother’s handbag,’ he told me. ‘You must make sure it goes with her.’

I gasped. ‘When will she leave?’

‘Sit down, Mrs Parr.’

I did so. We listened to the screams in the sitting room. If she didn’t stop, I’d have to go back in there. But just then Pamela gave a choking sigh, and Elizabeth’s voice came to us, muffled. ‘There, there,’ she was saying. ‘There, there.’

Constable Flack cleared his throat. ‘We don’t know what’s become of Mr Pickering. He scarpered long before the war, it seems. Nobody in Plymouth has ever seen hide or hair of hubby.’

‘Pamela hasn’t mentioned him …’ My breath fluttered out through my nostrils. ‘What were they doing in Southampton?’