Who is Rich?

The baseball field was at the far end of campus, inland, breezeless, and hot. You could smell fertilizer baking in the dirt. I watched an airplane fly along the bay towing a Geico banner.

Carl, the director, came across the field, lugging a duffel bag full of bats. He dropped it and jogged around the infield, ass bouncing, change jingling in his pockets, throwing bases on the ground. Then he sat, sweating heavily, on the other side of Tom and told us how much the bag of bats weighed, and where he’d lugged it from, and how an intern named Megan Donahue had locked the keys in the shuttle bus and the cops were on the way, and how the stage in the theater building had been shellacked two weeks ago but according to the theater people was still tacky, so the actors had to act in their socks so they didn’t stick to the floor. And the playwrights were all assholes. You had to call them “theater artists” or the “Drama Department” or they got angry. Then he pushed his long gray hair out of his face and went through the faculty, listing who was a piece of crap; anybody demanding a room change or failing to address students’ needs qualified, and this year, some of the new teachers seemed to be showing up with dietary restrictions or three names, like Alicia Hernandez Roulet. And the poets pronounced it “poe-eh-tray.” If it wasn’t for nice guys like Tom and me, he’d quit.

There was a certain headache you got after a day or so, the conference headache, which Carl already had. After three days you got a certain taste in your mouth, conference tongue. He told us how the administrators at the state U had lied and screwed him on funding, they were nickel-and-diming him to death, he had booze in his car that he’d stolen from Marine Bio and Sustainability—then we were quiet there on the dugout bench, and Carl asked Tom how much they paid him at other summer conferences. Tom laughed and said he never left the house for less than five grand but made an exception for this, since we had parties in the windmill.

More people straggled across the field; they seemed fine with the heat, pulling bats out of the duffel bag, dumping the bag to find helmets, testing swings, throwing and catching. Stan, a poet, claimed the mound to calibrate his underhand lob. An old lady with knee braces waited at the plate for batting practice. A security guard stood along the fence, and two women in beach clothes and visors sat in the stands. An able-bodied kid passed in front of the dugout, shirtless, barefoot, wearing jeans that had been shredded below the knee like a castaway’s—a fundamentally beautiful young person, covered in downy golden peach fuzz, handing out bottles of water.

A couple of conference-goers in bikinis sat on towels on the third-base line in front of the other dugout, and the able-bodied kid went over and gave them water, then spilled water on them and they screamed. He ran but they chased him and pulled him to the ground and pinned him and poured water on him. Everybody was having fun.

They were perfect and beautiful, whereas I was already a little revolting, although better straight on, but worse from the side. I was forty-two years old, obstructed by the limits of love, grasping at lust, scared to work on a crumbling marriage I’d be sure to hang on to for whatever remaining time we had here on earth.

A young woman dug through the mitts beside me and kept flapping them open and closed until I told her that a righty wears the thing on her left hand. I got a ball and went out onto the grass and showed her how to throw and catch. Her name was Eva Rotmensch. Some people pronounced it “Ava,” she said, but they were wrong. She walked with turned-out feet and had a flat pale face with a sharp jawbone and bluntly cut hair. She wore a cropped white blouse and pink shorts so fitted and tiny it would be difficult to imagine any underpants surviving inside them. When she raised her arms, her shirt went with them and I saw her thin torso. She needed me to know that she belonged to the theater company, as opposed to the theater workshop. Never played softball before, no sports, spent the first twenty years of her life in a dance studio. She pranced around on long, strong legs, like she was still onstage, mimicking my exaggerated throwing motion, elbow back, above her ear, and threw it over my head, then threw it into the bushes, then under the stands, waiting each time for me to go get it, like my daughter, who didn’t know how to do anything and needed me to show her, as though she were doing me a favor, turning whatever should’ve been fun into a pain in the ass.

I asked polite questions about her acting career, and mentioned a few out-of-the-way spots where people go to sunbathe, smiling at her, wondering whether she liked the beach, whether she liked swimming in big waves, feeling invisible and ignored, wondering what it would be like if for some reason she put down the mitt and lay on the grass and pulled down her shorts and begged me to fuck her.

Art historian Marilyn Michnick sat behind the fence, smiling and serene, and nearly blind, needing a cane, beside Alicia Hernandez Roulet, whose ugly little walleyed dog yapped around the field. Mohammad Khan, a theater critic, cleaned his eyeglasses with long, delicate-looking fingers, complaining about having to play. “I don’t like to get sweaty. I don’t like to be wet.” Vicky Capodanno came toward us from right field, in the baggy black T-shirt and shorts and combat boots she wore every year for softball, and a few steps behind her, Tabitha wore a baseball cap and a long thing you toss over a bathing suit that looked like a tablecloth. I recognized a couple stragglers, among them a taller lady moving stiffly, hunched and broad-shouldered in her gray sleeveless T-shirt and blue-and-green plaid shorts, who I’d spoken to a few minutes earlier: Amy O’Donnell, who I’d once held as we caressed in the dark, trembling and naked, and later while sleeping in the quiet dawn. I wanted another moment with her, something I could look back on later, to get me through another year, a scene, a place to park my soul through winter months of diapers and screaming.

I looked across the road, beyond the trees, to houses and a cornfield in the distance. Whatever hadn’t been watered was dead. A guy in a jungle hat took batting practice, drilling balls into left field, where eight or nine people stood chatting in two clumps, some of them not even facing the batter, and I wondered if one of them would be hit by a ball and killed.

Amy went behind the dugout and started stretching, some kind of hurried knee-bend squat. She was so tall. Her people could be traced back to the northern coast of Ireland, where shipwrecked Vikings raped the villagers, which made them tall and fair. She bent, she hunched, she made horrible faces. Now she squatted side to side.

The guy with the water came through the trees from the parking lot, and one of the girls in a bikini tried to make a run for it, shrieking, and he tackled her and spilled water on her and she screamed. They were young, although not so young, but like a different species.

“What’s his problem?” I asked Eva. “Why isn’t he playing?”

She watched him, lips parted, not smiling. She said his name was Ryan.

“Is he in the theater company?”

“He’s in something in New York, so he’s going back and forth, taking the train, so he can’t be in anything here.”

He rolled around on the grass—he had fine golden skin and a Chinese tattoo on his neck—as she watched him, her poor little blouse straining at every button, her ass floating in the air like a helium balloon. I threw the ball, but she wasn’t looking and it flew past her and pegged Stan in the back. He wheeled around, scowling, and kicked it away.

One of these nights, maybe after a rehearsal, under glittering starlight, Ryan might meet Eva walking from the theater to the dorms. And may it not turn into a long-term monogamous relationship, and may it end in a mutual hatefuck. Amen. Behind us, a group of interns stood blocking the dugout, looking sweaty, stealing our water, complaining to Mohammad Khan about having to clean up the tent after lunch.

“The kitchen is a total slime pit!”

“We’re totally covered in slime!”

They went on complaining as they tipped up bottles of water: a young woman in a torn miniskirt with torn black stockings and heavy mascara, and her sleepy-looking friend, filling out a T-shirt with the school’s name across her chest, and a third one with bouncy, eggy, shiny hair. It was as if the water they poured down their throats went right into their sumptuous breasts to keep them full.

Four more days of this. Then I could go home and choke my wife.

There were enough of us now to split into two teams. People wandered out to take positions so we could start.

I pictured myself heaving over some sullen nineteen-year-old, my baggy old face hanging down, and went along the dugout thinking filthy thoughts, grabbing helmets and lining them up beneath the bench, and asked nicely if anyone had the order, and saw that I was batting seventh. On this broiling Saturday afternoon, where were the cuties of my youth? Women in their forties had replaced them, hunching toward the grave. For so long I’d been young, but that was over, and the thing to do now was teach a little comics and go home, where I could drop my eyeglasses in the toilet, and fall down the stairs in my pajamas, somebody wailing in the background while I stood in my kitchen, in a state of shock, loading the dishwasher.

Vicky came over and put her mitt on her head and said, “Let’s get on with it already.”

I needed to find someone at this conference, someone who wouldn’t harm a married man, or hated being married, or couldn’t bear to be alone for three or four days. I didn’t have any big strategy here. I liked to flirt. I needed to stay alert every second for a potential alliance in this war against morbidity and death. Were there rules or prohibitions? Some of my colleagues preyed upon the young, their own students, the low-hanging fruit, which struck me as a real character flaw. I wanted a grown-up, maybe with children of her own, someone who was needed somewhere else and wouldn’t get hooked. I’d driven the many miles here with purpose and concentration. I had to make the most of my time away from home. Over the last ten years, the stuff I’d done could be counted on one hand: a couple of late-night goodbyes that never got past the talking stage; a wriggling blond woman at a convention in Brooklyn who edited textbooks for a living; Ruth Gogelberg, Gunkelman, whatever, at this very conference three or four years ago. It started when I was sixteen. It started when I was five, the need for a girl to save me, the need to escape, in a panic to get away from my mother and father, out of this empty shell. I always had a girlfriend, always fell in love, and even at my most saintly and sexless, I always liked someone out there, was working at something, moving toward it with intention and forethought, nibbling around the edges until I hated the whole thing, until everything I did became about not cheating, not doing something, until it was pretty much a foregone conclusion, and all I had to do was pull the trigger and get it over with, so I could slink back to my safe and stable perch and pretend it had never happened and hate myself and think of someone new.

Amy finished stretching and pulled her hair back into a rubber band. Our thing went beyond lusty one-liners and therapeutic confessions. I’d been in love with her for a year. Not love. Whatever it was. And it just so happened that her personal misery, hidden behind a windfall of prosperity, was ironically charged, luridly beguiling, and possibly useful in a practical sense, as fact-based material for the once and future semiautobiographical storyteller. She walked into the dugout. I stood and walked out, pretending not to know her. She found a bat and went behind the backstop and took practice cuts, swinging so hard her helmet fell off.

The game started. A big sandy-haired kid stepped into the batter’s box and golfed the first pitch high and gone; it landed in the parking lot, where it bounced as people cheered, as he ran around the bases with his arms hanging down, like a pigeon-toed ape. Mohammad Khan could barely lift the bat, and tapped a base hit. Tabitha got up and somehow outran a dribbler down the first-base line. Then Amy went to the plate, grimacing into the sun, and took a wild cut.

She hit it pretty well. The second baseman knocked it down but couldn’t hold on. He picked it up and tagged Tabitha softly on the shoulder, then threw the ball over the first baseman’s head, over the dugout, where it beaned the golf cart that had driven Marilyn Michnick here. Mohammad limped home. When the ball is thrown out of play, the runner is awarded the next base. Amy waited at first. I couldn’t stop myself and yelled, “Take second!”

She looked at me as though the last thing in the world she needed was a man yelling at her in public; she got enough of that at home. It was a confusing moment. I still had some investment or pride in her, I wanted her to thrive, succeed, whatever, so I stood in front of the dugout waving her on. She ran down the base path, unsure, reached second, and stared right at me as she stomped testily on the base with both feet. Stomped as though to defy me. But no one had bothered to anchor the base, so it skipped out from under her and she fell.

And didn’t get up.

The pitcher, Stan, walked to second base. The shortstop knelt. Nobody seemed to be moving. As I got closer, I saw that her whole mood had shifted; she’d come to a sitting position, her arm in her lap. She seemed drunk, the way a drunk is soft, sleepy, in shadows, fighting to stay awake; she was staring down into her lap as if a haze floated in front of her. Looking at her arm, I had to force myself to breathe. It was my fault, I’d done it. I pushed that thought away.

“What’s up?” Carl asked, standing so close he was brushing my shoulder. He hadn’t seen her fall. Then he looked. I watched his face change. She was sitting with one leg folded under herself, foot turned, knees bent, so that the whiteness of her inner thighs showed.

The girl kneeling beside her talked in a loud voice, holding Amy’s forearm. “Tip your head forward, that’s good, now deep breath, just relax, you’re gonna be fine, don’t look, it’s okay, I’ve got your arm,” and Amy saying, in a kind of husky, sleepy voice, “I don’t want to look,” and then a guy in a Red Sox cap came over and draped her arm with a T-shirt.

The security guard called for an ambulance. Vicky walked across the infield dirt, squinted at Amy, then turned to me. Our former and potential closeness made me think she could read my mind. My thoughts were slow and bleating and obstructed, but I noted, finally, that Amy had been a kind of home, a vessel for my discombobulated mind, that my own family treated me like a footstool but this stranger had cared for my soul. At some point, we could hear sirens on the highway. They decided to get Amy out of the sun, and with heavy assistance, she stood and took a few unsteady steps and began lowering herself down to the grass, her legs bending, collapsing, as her handlers bumped into each other, holding her arm, wavering, guiding her down, her legs folded beneath her, all wrong. They raised her up again as though it had been their fault.

“Ready?”

“Sure.”

And again she went down, and this time she tucked her chin and went completely out.

“Amy?” the girl said, kneeling. We all waited. “Can you hear me?”

“Uh-huh.”

“Do you faint easily?”

She nodded.

“I wish you’d told me that before. I wouldn’t have moved you.”

Amy’s gaze drifted down to the T-shirt covering her arm, as if it were some new friend. “I didn’t know until I fainted.”

An EMT and three paramedics arrived, asking a series of questions—name, day of the week, name of the U.S. president—and each time Amy answered politely.

“Can you move your fingers?”

“I can but I don’t want to, but thank you.”

The slapstick fainting, the bone snapped at nearly mid-forearm, crooked and flopping in the sleeve of her skin, not life-threatening but stomach-churning, her broken summer day, her arm lying in her lap, all of us standing over her as Carl used the security guard’s walkie-talkie. They strapped her to a red steel chair on wheels. I knelt down and attempted to communicate without making known any extramural bond between us.

“Do you want me to come with you?”

She shook her head. The whole bottom half of her face was trembling. Sweat or some kind of moisture pooled in her eyes. Carl signed off and handed the radio back to the guard. The hell with it. They wheeled her out.

Vicky stood beside me, sighing loudly, and when I looked at her she gave me a deep, penetrating stare. When I couldn’t come up with anything to say, she went behind the dugout and started smoking.

We resumed the game. Other people fell to the ground with injuries. Stan stumbled off the mound, holding his elbow. Luther Voigt pulled a hamstring. During my turn at bat I hit a fizzing pop-up, and felt something go in my back, and couldn’t stand up straight, and walking back to the dugout I used the bat as a cane, and watched from the bench as a string of elderly, scarred, limping septuagenarians hit and ran to the satisfying cheers of our team. I had one decent catch in left off a whistling line drive, and another off a deep fly ball. Both times I thought my legs would crumple and I’d fall to the ground, waiting for those balls to bang into my mitt, but I didn’t.

TWELVE

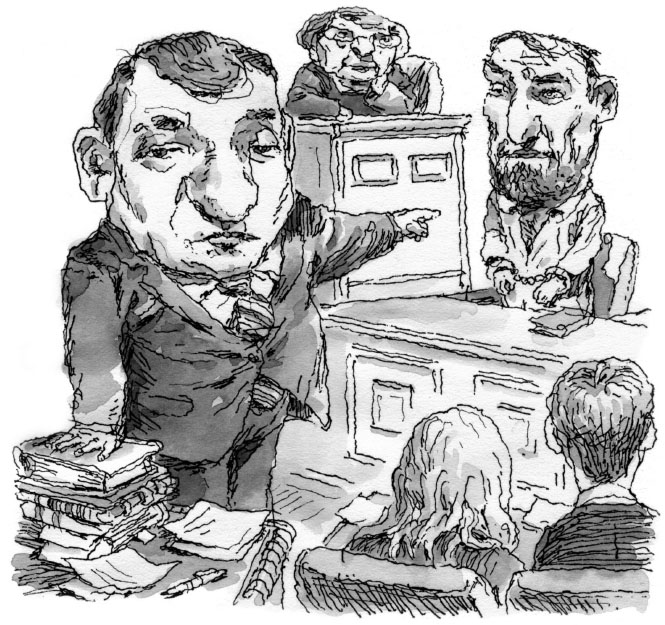

In February, I’d spent a week in New Hampshire, freezing to death on the campaign trail, sketching the GOP candidates as they trained their fire on Mitt. The front-runner tried to float above the fray, blaming Obama, smiling with dairy farmers, suggesting that ten million undocumented immigrants self-deport. The same speeches at horrible parties with terrible music and bad food.

Then in March I spent five days at the trial in Boston of the guy who tried to blow up Faneuil Hall, making drawings of the calm, fat-faced, and deliberate attorney general, of the bearded and scowling bomber, and the stolid and weeping families of victims. I wore credentials on a string around my neck, and got there at dawn to stake out a seat, and had nowhere to put my elbows, and learned about forensics, and a training camp in Yemen, and the destructive power of half a ton of nitroglycerin. After three days, my back was so stiff I couldn’t turn my head, which other members of the media found amusing.

I finished the assignment and drove south, toward Providence, and a little while later I was following Amy’s directions, imagining her on those roads, thinking that this was wrong and delusional, and also sleazy and immoral, which made me dizzy, but who cares. As I got closer, I thought of how racy it was, that the kind of guy who did this kind of thing was usually more chiseled. Turning deeper into rolling hills, darker woods, I figured I could get caught and lose everything and end up alone in a studio apartment with rodent feces and crackers in my beard. People make you do things you don’t want to do.

Over the winter, our ten thousand texts and emails had covered a lot of ground—holiday cookie recipes, the tale of the nanny who set the pizza box on fire and almost burned down Amy’s house—but also her hopes, regrets, embarrassments, and lots of stories about the man she’d married. She told me stuff she’d never told anybody, suicidal feelings in college, her father’s last words, a pitch meeting when Henry Kissinger spoke directly to her tits. By the time the weather changed, the novelty had worn off and our communications had hardened into something else, dogged, rambling, what we had for lunch, but also her fittings for ball gowns and other name-dropping tidbits of the .003 percent, the neighbor who bought a 737, the fund manager who poisoned a local river to get rid of some mosquitoes.

Amy had married a banker who made $120 million a year. He funded tea party candidates and didn’t believe in climate change. She’d left a good career to stay home and raise their kids in style. Sometimes, when he walked into a room, she felt goose bumps rising on her skin, a seething animal hatred, although it hadn’t always been that way. A world-class salesman, he’d sold her a bill of goods. He had a charitable heart, and a hospital in Latvia named after him that always needed cash. He was a soft touch on early childhood education, the third world, the urban poor. Although when I pressed her, she admitted that there were other things they agreed on. The federal government sometimes got in the way. The answer to our stalled economy would come through less regulation, with certain safeguards, which the president didn’t understand because he’d never run a business.

It was easier to ignore things in an email, elliptical phrases, insinuations. Her friends were generous, too, engaged in civic improvement in the Bronx, in farming projects in Togo. It had a certain logic, billionaires to the rescue, that kind of thing.

The emailing of our minutiae had a way of leveling the disparity in our fortunes. I told her how much it hurt to step barefoot on a piece of Lego, so she told me how much it hurt to trip over her son’s Exersaucer. We liked to pretend we lived parallel lives. My daughter and Amy’s younger girl, Emily, began worrying around the same time that if their baby teeth fell out, their tongues would fall out, too. How many times did we trade photos of adorable kids in pajamas or the bathtub, or end the night with a few pithy words, “dying for you” or something, that kept me buzzing for hours? How many nights did I lie in bed like a twelve-year-old boy from the pain of a thing so stubborn, imagining her over me, pressing myself flat, the cat draped across my dick, getting a contact high from the waves of desire coming off me—either that or its purring gave me a boner—but it was so real, I found myself whispering, almost touching her, knocking myself out in the dark.

She grew up in Leominster, Mass., the second oldest of six, or seven. A grandmother with a brogue lived down the hall. The family car had holes in the floor. She made sure I knew where she came from, that she’d had it rougher than me, which wasn’t saying much. Her dad stepped off the boat from Ireland, got drafted into the U.S. Army and shipped to Vietnam, and came home a patriot. Her mom missed Ireland, she thought Americans were crass, but loved nothing more than to sit down on a Saturday night to watch Lawrence Welk. Amy’s favorite sister, Katy, two years younger, married a cop. Her older brother sold fighter jets and missile parts to Taiwan. Lots of sidebars about her other sisters’ knee surgeries and blockages of breast-milk flow, their kids and husbands, their crummy office jobs. High school swimmer, track hurdler, vice president of her senior class. She was attacked the summer after high school ended, in a field beside the town pool. She told me how she thought he meant to kill her, and recalled the boy who found her, and wrapped her in his towel, and brought her home, and cleaned her up.

She put off college for a year. Worked in a photo lab, took up painting, dated a guy a few years older, but wouldn’t let him touch her. Went to a state school on a swimming scholarship, worked nights on campus security, wearing the orange windbreaker. Majored in econ, spent three years analyzing reports at an institutional bank, swore she’d never considered banking until she took the job. But hers was a small unit within a bigger bank, growing rapidly, and soon they moved her into sales, making presentations in high-yield. The women in her department were tall and good-looking, the men were retired professional hockey players, and they all did vicious things to try to steal one another’s clients. In place of any sort of imagination for a career path, she’d taken the formulaic route to some abstract idea of success, maybe hoping that one day she’d have security. Or a red Lamborghini. Earnest young people were drawn into an abusive, sexist, money-crazed environment, worked to death to prove themselves, to separate out the weak so that the only ones left were greedy, scrappy, stubborn maniacs.