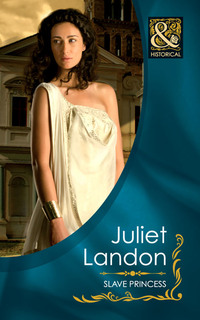

Slave Princess

If only she knew what the future held for her. If only her possessions had not been removed, then an attempt at escape might have been worth planning. But without shoes and only a linen tunic and a shawl to her name, no identifying ornaments, and no idea where she was, any plans would have to wait.

‘Where are my clothes?’ she said as soon as Florian climbed in, balancing a bowl of steaming broth in one hand.

His smile remained. ‘You’re sitting on them,’ he said.

‘What?’ She swivelled on the chest. ‘In here? And my ornaments, too?’

‘In there, with your shoes and clothes. Yes.’

‘I want to wear them.’

‘I expect you will, when my master decides.’ He took a spoon from inside his tunic, passed it to her and told her to eat while it was still warm. It was the first solid food she had eaten for over a week and, by its comforting warmth, the questions uppermost in her mind were released. Presumably to make sure she ate it, Florian stayed with her as the sky darkened ominously, the only source of light being the crackling fire outside that sent flickering shadows to dance across the canvas cover.

‘Who is he, your master?’ she said, passing the bowl back to him.

He spooned up the last leftover mouthful and fed it to her like a mother bird. ‘He is Quintus Tiberius Martial,’ he said, proudly rolling the words around his tongue. ‘Tribune of Equestrian rank—that’s quite high, you know—Provincial Procurator in the service of the Roman Emperor Septimus Severus. And before you ask me any more questions, young lady, you had better know that I am duty bound to report them to my master. I am the Tribune’s masseur, and I’ve been told to offer you my services, should you wish it.’

‘Thank you, Florian. It may be a little too soon for that.’

‘An apple, then?’ He pulled one out of his tunic where the spoon had come from, like a magician.

She shook her head, watching him unfurl, reminding her of a fern in spring.

‘It will rain tonight. Don’t worry about the canvas. It won’t leak.’ He looked round the wagon. ‘I’m impressed. You’ve been tidying up. We’ll make a handy slave out of you yet, I believe.’

‘That is one thing I shall never be, believe me,’ she said, severely.

‘Then try convincing the Tribune,’ he said, heading for the opening. ‘I think he’s rather set on the idea. But I told you that yesterday. Goodnight, Princess.’

She would like to have hurled the apple at his head, but a sudden wave of tiredness swept over her and it was all she could do to fall on to her pile of sheepskins and close her eyes against the murmurs and laughter outside.

The roar of rain upon canvas woke her. That, and the dim yellow glow inside the wagon, and the feeling that she was not alone. Instantly awake, her hand searched for the dagger that was always beside her. The habit died hard. It was not there.

‘Sit up,’ said a deep voice. ‘I need to talk to you.’

He was sitting on the chest, the smooth bronzed skin of his body almost aflame in the light from the lantern, his arms resting along his thighs, great shoulders hunched behind the head that hung low between them, his face turned in her direction. It was clear he’d been studying her for some time, for now he straightened up and stretched like a cat. He wore calf-length under-breeches of white linen, and his hair was damp-black as if the rain had caught him. And in the confined space of the wagon, he was much too close for comfort.

Grabbing at the blanket, Brighid pulled it to her chin and hauled herself up against the cushion. ‘I don’t wish to talk to you,’ she retorted, breathlessly.

‘I was hoping you wouldn’t. I need to talk to you,’ he repeated.

‘Yes, you do have some explaining to do. How long does this journey last? And when can I have my possessions returned?’

‘I don’t need to explain myself to slaves,’ he replied, looking her over again, measuring her up with his insolent eyes.

‘I am not a slave!’

‘Oh, don’t let’s hear all that again. Florian’s had enough of it and I don’t intend to hear it. The facts are, woman, that you have no choice in the matter. The Emperor has ordered me to take you off his hands and to do what I like with you; as far as I’m concerned, that means selling you on to the next slave merchant we meet on the way.’

‘You wouldn’t do that! No … you couldn’t!’ she cried.

‘I assure you, lass, I would and I can. I don’t have a place for high-and-mighty princesses in my line of work and I don’t intend you to spoil my holiday, either. Lindum will be the end of the line for you. Our next stop down the road. We’ll be there by this time tomorrow.’

The blood ran cold along Brighid’s arms. He wanted rid of her. She had seen the slave merchants and their shocking filthy tricks, the humiliated women, the wealthy leering buyers. Of all fates, that would be the most shaming. Her teeth chattered as she tried desperately to keep a tight hold on her dignity, not to show her stark fear. She was a chieftain’s daughter. She would not plead. Not even for this.

‘If the Emperor wanted me off his hands, Roman, then why did he have me taken in the first place? Does your Emperor not know what he wants, these days? Could he not have ransomed me?’

‘His men were too eager. It’s common enough. They thought he’d have a use for you. He doesn’t. Not for a woman of your rank whose death would be on his hands in a month or so, if you had your way. He’s not come all the way to Britain to make trouble, but to stop it. Nor is he interested in ransoms. Of what worth is a woman?’

At one time, she thought, she was worth plenty. Now, very little. With pride, she was about to tell him how the Dobunni tribe had wanted to buy her and how Helm and her father had discussed deep into the night how much gold, how many cows, pigs and sheep must change hands for her. But that was pointless, and in the past, and the less this man knew about her, the better. But she must do something, say something to make him keep her with him until they reached the south. ‘I would have thought, Roman, that as soon as my disappearance was discovered, the trouble the Emperor wishes to avoid will double or treble in the next week or two. Does that not concern you?’

‘Why should it? All the more reason why you should be out of the way as fast as possible. Has anyone come to find you? No messages?’

She did not need to answer when her face reflected her despair.

‘Tell me something,’ he said, leaning forwards again, glancing up at the sound of thunder. ‘Do all chieftains have their daughters taught to speak as the Romans do? You have a good accent. You’d fetch a good price as a noblewoman’s maid.’

‘The Briganti know that high-born women are most sought after by other tribes if they speak in the Roman tongue. It’s useful to them. We are not the barbarians you think us to be, Roman. My brothers and I were taught well.’

‘And have you been sought after?’ he asked, softly.

‘Yes.’

‘By whom? Are you married to him?’

‘No. You ask me too many questions, sir,’ she said, holding her burning cheek.

‘You may think so, but the question a slave merchant will ask me is whether you are a maid or not. Are you?’

Subconsciously, in a gesture of crushing fear, she drew her knees up to her chin and laid her cheek upon them, turning her burning face away from his scrutiny. ‘No one except my kin may ask me that,’ she whispered.

‘I can soon find out,’ he said.

‘No … no, please! I’ve had nothing to do with a man. It was never allowed. Other girls of the village, other women, but not me. I would be worthless, otherwise. Besides, there was no one.’ Her voice tailed away, her mind turning somersaults over the hurdles of pride versus safety. He needed to know how much she’d fetch on the market, not how much use she’d be to him personally, which is what she’d thought earlier. And now she would have to change his mind, offer him something to keep her with him all the way to the Dobunni territory. She would have to plead, if necessary. It was something she was unused to, except to the gods. ‘Give me more time,’ she said, ‘until I’m stronger. Until we get to wherever we’re going. I’ll keep well out of your way. I shall cause you no trouble.’

The rain drummed on the canvas as he said nothing in reply, until he straightened up again as if he’d come to a decision. ‘I wonder what you’d look like in Roman dress,’ he said, thoughtfully.

Hope flared briefly in Brighid’s breast. ‘I’d look like a Roman citizen,’ she said. ‘And I’d behave like one, if I thought my life depended on it. Is that what concerns you? My clothes? My appearance?’

‘Would you behave like one? I have my doubts.’

Her head lifted, poised elegantly upon the long neck, while her hands fell away from her knees and rested in graceful curves upon the blanket. ‘Try me,’ she said. ‘Give me a chance. I don’t want to be sold. I’m not ready to be anyone’s slave. Whatever else you wish, but not that.’

‘Your readiness is not my concern, lass,’ he said, yawning as he stood up. ‘Captives are rarely in a position to bargain about their future, and you’re no different, princess or not. You are my slave. Better get used to it. I’m tired. We’ll decide on this in the morning.’

‘Then it would have been better to let me die at Eboracum with my maid, Roman. That way, I would have been free.’ Throwing off the blanket, she stood up in one swift unbend of her body, intending to put more distance between them. Earlier that day she had felt a reason to stay alive, to seek the help of the man who had wanted her, even though he would never have been her choice if she’d been less high born. Now, the tables were turned, and it looked as if her flimsy plan had all but vanished.

The soft mattress hampered her feet, the curve of the canvas was not designed for her height, and the long reach of Quintus’s arm caught her wrist in an iron grip, pulling her off balance. Furiously, she tried to throw him off, her eyes blazing with green fire. ‘No man may touch me!’ she yelled, competing with the roar outside.

‘Then that’s another thing you’d better get used to, Princess High and Mighty. And if this show of temper is meant to convince me that you can behave in a civilised manner, then you’ve fallen at the first jump, haven’t you? And mind that lamp, for Jove’s sake!’ His swinging her round sent her sprawling against the chest. ‘Any more nonsense, woman, and you’ll find yourself shackled to a slave-merchant’s line-up at Lindum. If you doubt me, just try it. I have no taste for ill-tempered barbarian women.’

She knew it was a mistake. Righting herself, she pulled her legs under her, covering them with the linen tunic that was not quite long enough, bowing her head submissively. ‘Forgive me,’ she whispered. ‘I feel my losses deeply. If I lost my freedom once more, permanently, I would take my own life and forfeit the protection of the goddess Brigantia, after whom I am named. She is angered that I no longer wear her gifts, nor have I offered at her shrine since my capture. I am not the bad-tempered barbarian you think me. I grieve for my maid, her lost child and for my family, but I have no way to relieve it, Roman.’ With downcast eyes, she could only feel the pad of his bare feet as he took a stride across the mattress to lower himself between her and the side of the wagon, only a hand’s reach away. Thunder still crashed overhead. ‘She’s angry,’ she whispered. ‘Very angry.’

‘I thought goddesses were more understanding than that. Your Brigantia must be a very vengeful dame. They mean so much to you, do they? Your ornaments?’

‘She gave them to me when I was born. I began to wear them when I became a woman,’ she said, plying and unplying the fringe of the blanket. ‘They are a part of me. If I lose them, I lose who I am. That’s the reason, I suppose.’

‘The reason?’

‘The reason why I’m losing myself. I shall be someone else’s property, not my own woman. I do not know if my spirit can rise above it. I have yet to find out.’

‘So what if you were to wear them again?’

Her head lifted at that. ‘You would allow it?’

Quintus blinked at the gaze she fixed on him, moved by the strange unearthly power of blue-green waters that shimmered off the coastline of his beloved home, Hispania. He saw the sun and sea, vineyards and villas, warmth and good friends who asked for nothing but friendship. He saw it all in her eyes, felt her grief, as if her losses were his losses also. ‘Tomorrow morning you shall have them. Meanwhile, they’re in there and you’re sleeping next to them. Your goddess surely won’t mind that so much.’

‘Thank you, Roman. Oh … thank you!’ Her fists clenched over the fringe. ‘I must not weep,’ she whispered. ‘I must not weep. I am strong.’

‘And perhaps we’ll find a way of making a portable shrine to Brigantia. Wait till we reach Lindum. There’s sure to be something on the market. ‘Tis a terrible thing to lose touch with your own deity.’

‘Then you’ll allow me to stay with you? Not sell me?’

‘For the moment.’ He yawned again, covering his white teeth with the back of his hand. ‘But let’s get one thing straight, shall we? Whether you wear Brigantia’s gifts or not, whether you think of yourself as your own woman or not, that fact is that you remain my property. I have orders to get rid of you, and that’s what I shall do. It’s all a matter of how and when. I doubt whether your goddess will approve, but that’s how things are. Understand that from the beginning and your chances of staying alive will improve. You’ll have to learn to adapt, Princess. You’re not very good at that, are you?’

‘I will try,’ she said. ‘I can learn. Truly, I will learn, Roman.’

‘So learn to address me with respect, if you will. To you, I am Tribune.’

‘Yes. And I am known as Brighid, sir.’ She pronounced it ‘Bridget’.

Quintus, however, did not. ‘To me, you’ll be known as Princess. It suits my purposes,’ he said, curtly.

Ah, she thought. More saleable. As with the gold ornaments. These Romans so love display, don’t they? Especially on a woman.

Bending across to where the lantern stood in one corner, he opened the shutter and nipped the wick, plunging the wagon into complete darkness that seemed to intensify the rattling of the rain on all sides. The blanket was pulled out of her hands as he held it to open the bed, and his sharp command, ‘Lie down!’ took her completely by surprise as his legs burrowed downwards and a cushion was pulled from behind her.

‘What!’ she yelped. ‘No … no, sir! You cannot stay here!’

His arm came heavily across her, but the chest was at her side and there was no way out of the predicament. ‘Listen, woman,’ he said. ‘Either I sleep in here, or I get those two guards to take my place. They’ll be warm and dry at the moment, and I doubt they’ll be too honoured to spend the night cramped up in here. You choose.’

‘You don’t understand, sir,’ she said, trying to prise his arm away. ‘I have never slept with a man.’

‘Then don’t sleep. Stay awake, if you prefer. This will be another new experience for you to learn. Come on. Wriggle down. You’ll be quite safe.’

The notion of keeping her distance had to be abandoned as she slid down beside the warm bulk that took up more than half the mattress, the only room for protest being to turn her back on him. But he wrapped the blanket over her, pulling her into the bend of his body and resting his arm on the gentle swell of her hip, and though it was not an uncomfortable ordeal for her, her whole being was alive to his intimate closeness, his warmth along her back from neck to ankle, the disturbing male scent of him, his strange contours. She had seen the village men naked, half-naked and all stages in between for there was no privacy to speak of at home in the communal huts. But she had seen no man’s body as beautifully crafted as this one’s, honed to perfection, pampered by his personal masseur, probably adored and satisfied by countless women. He was unwilling to have a woman of her kind in tow, even for the novelty value of owning a Brigantian slave, yet she had neither seen nor heard any other woman in the cavalcade.

‘Don’t you have a woman to go to?’ she muttered, resent fully.

‘Yes,’ said the voice, rumbling into the cushion. ‘I’m with her. Go to sleep. We have to be away by dawn if we’re to reach Lindum tomorrow.’

The beating of the rain lulled her to sleep long before she heard the thunder pass on to disturb other miscreants. Once she woke to hear the gentle hiss of rain, when she reached out a hand to touch the chest where her treasures lay, and fell back into sleep. The next time, there was silence except for the soft breathing of the man behind her. She wanted to turn, but her tunic was caught under him and she could not free it without waking him.

‘What is it?’ he whispered.

‘You’re lying on my tunic. And my hair.’

There was a huff of amusement as his hand delved and freed her hair, then, before she knew what he meant to do, he hauled on the other side of her tunic, rolling her over to face him, to be enclosed in his arms, her mouth against his firm jaw, her legs pressed against him. Her breasts lay upon the great mound of his chest, taking the heat of him through the linen, and when he laid her thick plait across his own neck like a winter muffler, she knew he intended her to stay and to sleep again, safe in his arms.

But sleep was hard to recapture when her head was being held in the crook of his neck, his mouth only inches away from hers, his arm cradling the soft red mass of her hair. Carefully, to ease it, she laid her leg over his, thus unwittingly inviting his free hand to slide gently over the roundness of her buttock and along her thigh, eventually sliding under the linen to find her silken skin.

She made a grab at his hand. ‘Please … Tribune … no!’ she said, fiercely. ‘I cannot … will not … do this with you. You told me I was safe.’

She felt his smile on her forehead as his lips brushed against it. ‘Then what was all that about learning to adapt?’ he said.

‘For pity’s sake, give me more time,’ she said, clinging to his hand.

‘Let go, lass. Time enough.’

But would there be time enough? she wondered, as she listened to the camp begin to stir outside. Would she still be a maid when she found Helm, or would he reject the used goods she had travelled all that way to offer him, all at the Tribune’s whim?

Chapter Three

‘So, my friend,’ said Tullus, rather smugly, ‘you took our advice, I see.’ His cheek bulged as he chewed hungrily on his loaf while he searched in the pan for another piece of bacon to follow it.

‘You see nothing of the sort,’ Quintus replied, holding out his beaker to be filled. ‘If I had not slept there, who would?’

That was too much for Lucan. His loud laugh turned heads in their direction. ‘Oho, the martyr!’ he chortled. ‘You had only to ask us. One of us would have obliged, to save you the discomfort.’

‘Well, save yourselves any more speculation. She has to stay virginal for the Dobunni lad to want her still. If she’s not, she’ll be of no use either to him or us, will she? That’s the first thing he’ll want to know.’

Tullus nodded agreement. He was the more serious of the two juniors, with an attractive contemplative quality that intrigued his female friends, especially when his deep grey eyes studied them with a flattering intensity. Unlike the feline grace of his friend, Tullus was built more like a wrestler who tones his body with weights, swimming and riding as much as his office work would allow. Quintus liked them both for their superior accounting skills and for their loyalty to him, putting up with their banter as an elder brother with his siblings. ‘Does she know about her father yet?’ said Tullus, licking his fingers.

‘No,’ said Quintus, sharply. ‘It’s not a good time to tell her when she’s just lost her maid.’

Lucan looked at him and waited. None of this was good timing when they were looking forward to some time off. ‘She’s accepted the situation, then?’ he said, hoping for some clarification.

‘Far from it. I’ve told her I’ll sell her before we reach Aquae Sulis if she doesn’t toe the line.’

‘But you wouldn’t, would you?’

‘Of course not. But she doesn’t know that,’ Quintus said, wiping a finger round his pewter dish. ‘But nor can we cart her through our hosts’ houses looking like something from the back woods. That would take more explaining than it’s worth. She’s going to have to dress up.’

‘Like a Roman citizen? That should be interesting.’

‘It will be. This is where I need your support.’

‘Go ahead,’ said Tullus.

‘Except for one, our hosts don’t know us. I just happen to own a slave who’s a Brigantian princess. Right?’

‘Unusual, but I don’t see why not,’ said Lucan. ‘Go on.’

‘Well, that’s it, really. I shall not present her. She’ll stay in the background in my room with Florian. She’ll be safe enough with him.’

Lucan and Tullus nodded, smiling in unison. ‘And how long has this … er … relationship been going on? In case we’re asked?’ said Lucan, innocently.

Quintus stood, brushing the crumbs from his lap. ‘Since a few days ago, I suppose. But I don’t see why anyone needs to know. I’ll get some proper clothes for her at the next market.’ He stood still for a moment with a pensive look in his eye.

‘What?’ said Tullus. ‘You doubt she’ll accept them?’

‘Nothing more certain. Find a barber before we reach Lindum, both of you. Now let’s get this lot moving. Come on.’ He strode away, shouting orders.

Lucan released his grin at last. ‘Halfway there,’ he whispered.

‘Oh, I think that’s rather too optimistic, my friend,’ Tullus replied. ‘From what I’ve seen of her, I’d say she’ll keep him on the hop for a while yet. What’s going to happen when she hears about her father?’

‘Expect all Hades to be let loose. Do I really need a barber?’ Lucan wiped a hand round his blue jaw.

‘If the boss says shave, we shave. We owe it to our hostess. D’ye know, I’m looking forward to a decent bed.’

‘As will our boss be. He’s pretending, you know, that she’s a bit of a nuisance—I believe he’s quite taken with her.’

‘That’s the impression I’m getting too. There’s a new spring in his step.’

‘As there would be in yours, young Tullus, after a night with the Princess.’

Brighid was shaken out of her sleep by a gentle hand on her arm. ‘It’s late,’ Florian was saying in her ear. ‘The camp is already packing up. Wake, or you’ll get no food. Did the Tribune keep you awake all night?’

She rolled herself upright, pushing away her loose hair. ‘Mind your own business,’ she said. ‘What’s all that din?’

‘We’re almost ready to leave. What do Brigantian princesses eat for breakfast these days?’ he said with a knowing grin.

‘Porridge, and a thin slice of masseur’s tongue, if you’d be so kind.’

‘Tongue’s off,’ he quipped, ‘but I’ll find you some stodge, if you insist.’

‘Clear off while I get dressed. Where can I go and bathe?’

Florian paused at the tail-board. ‘Bathe, domina? I would not recommend it. Not here. Not unless you want an audience.’

‘Then how am I ever going to get cleaned up?’

‘Better do it in here until we reach our lodgings. Wait. I’ll bring some water.’

The extraordinary events of the night came back to her as she unravelled the blankets and saw the pillow with the dent in it close to her own. He had left without disturbing her, she who always woke at the slightest sound. Even more remarkable was his opening of the chest beside her where now her treasures lay in a row on top of her folded clothes, set out for inspection like a soldier’s kit.

Even by Roman standards, the pieces were of the highest craftsmanship, technically perfect. The most impressive was a flat crescent-shaped neck-collar with a raised pattern of sinuous spirals studded with cornelians and lapis lazuli, and inlaid with coloured champleve enamel. One bracelet was a wide band of beaten gold with triskeles, sun discs and lunar crescents in relief, the other was fashioned like a coiled serpent with rock crystals for eyes. Her earrings were the delicate heads of birds with garnet eyes, spheres hanging from their beaks chased with spirals, as intricate as man could devise. There was a pile of anklets of twisted gold, a belt with a gold enamelled buckle, several brooches and long hairpins with gemstone tops. Gathering them on to her lap, she fondled them lovingly.