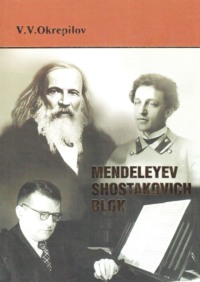

Mendeleyev. Shostakovich. Blok

Making suitcases and frames for the portraits was another passion of Dmitry Mendeleyev, which became surrounded by legends and rumours. Mendeleyev always bought the materials for the work at Gostiny Dvor. Once, while choosing the necessary goods, he heard somebody asking behind his back: “Who is this respectable gentleman?” And the answer of the clerk: “It is necessary to know such people. This is Mendeleyev, a suitcase-maker.” In general, Mendeleyev liked to paste. It was a rest for him as well as patience or chess. He pasted very neatly and accurately, he sticked on the collections of photographs and engravings of Russian and foreign famous pictures, collected by him, he pasted cases for the albums and brochures, boxes, caskets, small travelling cases. His niece N. Y. Kapustina-Gubkina kept a folding traveling chess-board, made by Dmitry Ivanovich. The pasteboard figures were set into the special squares and they couldn’t fall out of them on no jolting on the road. In 1895 Dmitry Ivanovich couldn’t read and write after having had an operation of the cataract ablation: he had been read the papers aloud, he had been dictating the instructions to his secretary. And till his eyesight hadn’t come back once and for all, Mendeleyev devoted his spare time to this passion, having presented all his friends with suitcases, boxes and caskets.

Mendeleyev paid pretty much attention to the scientific research of spiritualism. He studied the phenomena, happening during the spiritualistic sessions, as a scientist and pedagogue, as far as the passion for spiritualism by many professors of the University could have influenced the student youth. He suggested to establish the special commission for studying the spiritualistic phenomena, attached to the Russian Physical Society. Well-known physicists and chemists took part in it in addition to Dmitry Ivanovich: I. I. Borgman, N. A. Gezehus, N. G. Egorov, K. D. Kraevich, F. F. Petrushevsky, etc. While studying the “spiritualistic phenomena”, the methods of natural sciences, instruments and calculations were broadly used. The conclusions of the commission were joined in the book, published by D. I. Mendeleyev, “The materials for commenting the spiritualism.” The funds, made by selling this book, were meant for “making a big balloon and in general for the research of the meteorological phenomena of the top layers of atmosphere.”

The versatility of personality and variety of interests of Mendeleyev are striking. But the scientist himself used to say so: “I respect one-sided talents, but, nevertheless, I consider them to be a certain abnormality. I like science most of all, but I think that I could have specialized in other spheres under the certain circumstances. I think that a normal person can orient everywhere.”

Mendeleyev was depressed by the end of the 1870’s. The state of his health had become worse. He had been taken ill with pleurisy and he had to go abroad for the treatment. Besides, his relationship with his wife Theozva Nikitichna was cooling down more and more.

In spring of 1877 his wife with the children goes to Boblovo. And the sister of Dmitry Ivanovich Katya comes temporarily with the children to his apartment. Anyuta Popova, the daughter of a Don Cossack, lived as a guest with Nadezhda, the niece of Mendeleyev. She studied at the Conservatoire in the class of piano; she visited the painting school attached to the Academy of Arts. Infatuation of Dmitry Ivanovich for her grew into love. However, Anyuta was more than 20 years younger than Mendeleyev. They were called Faust and Margaret behind their back.

Dmitry Ivanovich suffered deeply while struggling with his feeling. He considered necessary to tell everything to father of Anna Ivanovna, and the last one asked him not to meet with Anyuta anymore. The girl went abroad, but Mendeleyev followed her to Rome. In 1881, after having returned, he wrote to Theozva Nikitichna: “Yesterday I came back to Petersburg with Anna Ivanovna and her father Ivan Eustacievich…

My position is clear and specified already by this. If nothing extraordinary happens, it will stay being like that, and I will stay at the University, I will start lecturing and working as usual, and, in addition, I will solicit to have funds for 2 families.” “We’ve lived, we will stay being friends though not in one house.”

Theozva Nikitichna hasn’t agreed for the divorce for a long time. The marriage was dissolved only in 1881. In winter of the same year Lyuba, the daughter of Anna Ivanovna and Dmitry Ivanovich, was born. They could get married only in 1882. After the wedding the Mendeleyevs settled in the university apartment. Here their younger children were born later: a son Ivan and twins, Maria and Vasiliy, who were called in honour of the mother of Dmitry Ivanovich and his uncle Vasiliy Kornilyev, who had done many things for the Mendeleyevs in his time.

This period was a hard one for D. I. Mendeleyev also by another reason. It seemed to him that he didn’t have enough energy in order to realize his creative potential sufficiently. However, he kept working, and the periodical law, discovered by him, got more and more followers among the scientists of the world.

From the very beginning appeared the question of the priority of the discovery, started by the number of English and German scientists: W. Odling, L. Meyer, etc., in connection with the fundamental importance of the law. Mendeleyev devoted his publication “To the question of the system of elements”, which appeared in the “Reports of German Chemical Society” in 1871, right to this problem. In his small article the scientist mentioned the most important stages of his discovery and suggested for the first time to call his system periodical, because of the periodical law being its basis: “The measurable chemical and physical characteristics of the elements and their connections depend periodically on the atomic weights of the elements.”

The article “The periodical legality of the chemical elements”, which was the result of more than two years of work of the scientist, was published in 1871 in the “Annals of Pharmacy” (“Annalen der Pharmacie”), the oldest chemical magazine, founded in 1832 by the German chemist J. Libich. That is the evaluation of this article by Mendeleyev at the end of the 1890’s:

“This is the best code of my opinions and considerations about the periodicity of elements and this is the original, according to which there was written so much about this system. This is the main reason of my scientific reputation…”

In the same article the scientist gave the criterion of the solidity of the laws of nature in general: “Every law of nature gets the scientific meaning only in case that it, so to say, allows practical consequences, i. e. such logical conclusions, which explain unaccounted and point to the phenomena unknown before, and especially if the law leads to the predictions, which may be checked by experiment. In the last case the meaning of the law is evident and it is possible to check its equity, which at least impulses to the development of the new spheres of the science.”

By applying this thesis to the periodical law, he mentioned the following opportunities of its application: 1) to the system of elements;

2) to the definition of the characteristics of yet unknown elements;

3) to the definition of the atomic weight of scantily explored elements;

4) to the correction of the values of atomic weights; 5) to the renewal of the data concerning the forms of chemical compounds. Besides, Mendeleyev pointed to the possibility of “application of the periodical law: for the correct idea of the so-called associated compounds; for the comparative research of the physical characteristics of simple and compound bodies.” Mendeleyev thought when the physical sense of the periodical law would have been understood and the essence of the elements’ distinction would have been discovered on this basis, “then, certainly, chemistry would be able to leave the hypothetical field of static ideas, which are dominating there nowadays, and then there would be an opportunity to place it under the dynamic direction, which is already applied productively enough to the study of most of the physical phenomena.”

It is possible to say that the scientist outlined by this article the broad programm of the research on the subject of inorganic chemistry, based on the law of periodicity. Indeed, many important directions of inorganic chemistry were developed actually at the end of the 19th – beginning of the 20th century according to the ways, designed by D. I. Mendeleyev.

In March of 1879 there was an important event, which promoted the further consolidation of the periodical law in the science: the Swedish chemist L. Nilson told about having discovered scandium, which appeared to be the same with ekabor of Mendeleyev. However, L. Nilson defined the chemical nature of scandium incorrectly first, holding that the new element should have been placed for certain between tin and thorium in the periodical system. The identity of scandium and ekabor was clearly determined in August of 1879 by the countryman of Nilson P. Kleve. And in 1880 L. Nilson admitted the rightfulness of P. Kleve.

Thus, if the discovery of gallium by P. Lecock de Boibodrant in 1875 only confirmed the opportunities of the periodical system, the discovery of scandium made the chemists look at it as at a strict scientific generalization of data and facts, as to the guide to the further research of chemical elements. In 1884–1887 the periodical law became consolidated and was acknowledged by the vast majority of those scientists, who hadn’t made a proper account of it or ignored it at all.

In 1884 the “problem of beryllium” was finally solved. Up to that moment there hadn’t been any united standpoint concerning the valency of this element and the value of its atomic weight. On April, 17th (5th) L. Nilson wrote a letter to Mendeleyev, where he was stating all the data concerning beryllium and was warmly congratulating him with the fact, “that also in this case, as in many others, the system justified itself.” The discovery of the new chemical element germanium in the rare mineral argyrodite, made by K. Winkler in 1886, became an especially important event of that time in the fortune of the teaching of periodicity.

That was the triumph of the periodical system of elements. It was totally acknowledged by the scientific world. And Mendeleyev himself reacted to the discovery of germanium in a very unusual way: in May of 1886 he made a special photomontage of the “consolidators of the periodical law.” This photomontage, pasted to the mat, consisted of four portraits: P. Lecock de Boibodrant, L. Nilson, K. Winckler and B. Browner. On the back side, in front of each portrait, there were made notes by the hand of Mendeleyev, which were briefly characterizing the accomplishments of the scientist.

The authority of D. I. Mendeleyev was growing among the scientists of the world. However, everything wasn’t so easy in Russia. The news about D. I. Mendeleyev having got married to Anna Popova without having had divorced with the first wife caused many rumours and gossips. It was even rumoured that the actual bigamy of the scientist became the reason of Dmitry Ivanovich’s having not being elected to the academy. A joke even was said during those years: when one of the generals applied to the emperor with a request to give him a permission for the second marriage, Alexander III refused definitely. And when the general reminded that Mendeleyev had had two wives and nothing had happened, the emperor answered: “That is true, that Mendeleyev has two wives, but I have only one Mendeleyev.” But, certainly, there was another reason of Mendeleyev having not been elected to the actual members of the Academy of Sciences. The scientist’s relationships with the officials in the government as well as in the scientific circles were far from cloudless. Mendeleyev himself after having visited once the Ministry wrote in his diary: “Never have I been to put on airs, to kowtow before anybody, and it is necessary for them to do both, there isn’t any middle. May their kingdom flourish – it isn’t a place for us – it is humiliating, it is bad to become trivial with them, you want to cry and anger is overcoming.”

The question of electing Mendeleyev to the actual members of Petersburg Academy of Sciences was raised at the beginning of 1880. Naturally, the scientific activity of D. I. Mendeleyev was connected from the very beginning with the Academy. He had many friends there: J. F. Fritzsche, N. N. Zinin, E. H. Lenz, A. M. Butlerov, etc. The articles of Mendeleyev were being published repeatedly in the editions of the Academy of Sciences. In 1876 D. I. Mendeleyev was elected a Corresponding Member of the Academy of Sciences without any specific difficulties. The candidature of D. I. Mendeleyev was suggested by G. P. Gelmersen, N. I. Koksharov, F. B. Schmidt, A. V. Gadolin and A. M. Butlerov. 17 from 20 presented voted for him. It is possible to explain the success of the elections also by the impression, which had been made upon the scientific world by the discovery of gallium by Lecock de Boibodrant.

In March of 1880 there was established the commission attached to the Department of Physico-Mathematical Sciences, which was to nominate the academician candidates to the chair of technology and chemistry. The fact is that at the beginning of February of 1880 academician N. N. Zinin died. The “chair” of the academician “in the sphere of technology and chemistry, adapted to the arts and crafts” became empty.

Butlerov, Koksharov, physicists Wield and Gadolin were the members of the commission. Butlerov nominated two candidatures: D. I. Mendeleyev and professor N. N. Beketov from Kharkov University. Both scientists were at the chairs of “pure” chemistry at the universities and formally couldn’t claim to the vacant post of academician at the chair of technology and chemistry. But Butlerov hadn’t found worthier candidature. The commission hesitated in the choice between the two scientists. Beketov had learned about it and agreed that it was necessary to nominate Mendeleyev in that case.

While characterizing the candidature of D. I. Mendeleyev, academicians A. M. Butlerov, P. L. Chebyshev, N. I. Koksharov and F. V. Ovsyannikov noted his extraordinary accomplishments in the science: “Professor Mendeleyev takes first place in Russian chemistry, and we dare to think, sharing the general opinion of Russian chemists, that the place in the primary class of the Russian empire belongs to him by right. By adding professor Mendeleyev to its milieu, the Academy will honour the Russian science and, therefore, itself as its spiritual representative.”

Mendeleyev started preparing the speech, which he was to pronounce after the election. The speech was named “Which Academy do we need?”. The necessity of changes was its main topic.

Indispensable secretary of the Academy of Sciences K. S. Veselovsky tried to disrupt the balloting. He advised the president F. P. Litke to use the “veto” so that the elections would not have taken place at all. However, the elections took place in November of 1880. 18 people took part in it: 16 members of the physico-mathematical department, the president who had had two votes and the indispensable secretary. Exactly the half of the staff of the Department of physico-mathematical sciences seconded the candidature of Mendeleyev. The University scientists were the supporters of the election: A. M. Butlerov, P. L. Chebyshev, N. I. Koksharov and A. S. Famintsyn. Indispensable secretary of the Academy K. S. Veselovsky was one of the main opponents. Mendeleyev lacked four votes to become an Actual Member of the Academy of Sciences. The academic majority has blackballed the scientist.

The paper, where the approximate allocation of the forces was written by the hand of Butlerov: “It is evident – the black ones: Litke (2), Veselovsky, Gelmersen, Schrenk, Maksimovich, Strauch, Schmidt, Wield and Gadolin. The white ones: Bunyakovsky, Koksharov, Butlerov, Famintsyn, Ovsyannikov, Chebyshev, Alekseev, Struve and Savich.”

The voting against Mendeleyev broadly echoed in the press. The question of the reasons of having not elected the scientist to the members of the Academy of Sciences is rather disputable. The contemporaries mentioned different versions: “intrigues of German party”, a difficult temper of D. I. Mendeleyev, a competition between the Academy of Sciences and Saint-Petersburg University. It is also necessary to take into consideration the fact that the periodical law was one of the items, according to which Mendeleyev was recommended for academician, hasn’t absolutely consolidated in the scientific world and raised certain doubts yet.

Protests from different institutions and organizations fell to the Academy of Sciences. Mendeleyev received hundreds of sympathetic letters. During the small period after having been blackballed Mendeleyev got about 20 diplomas of the status of honorary member of the number of Russian universities and scientific societies.

Dmitry Ivanovich took hard the failed elections for academician, though the general attention and reaction of the press seemed to worry him more. He wrote in his letter to an old friend of him, the professor of the University in Kiev, P. P. Alekseev: “… I didn’t want to be elected to the Academy, I would have been discontent with it, because they don’t need there what I may give, and I don’t want to reorganize myself anymore. There is neither foreign pomposity, solid firmness in the object of studies, nor the affected religious rite in the temple of science may be in me, if it had never been.” Telegrams and sympathetic letters worried Mendeleyev. However, later Dmitry Ivanovich came to a conclusion that he was only a cause, thus, it was expressed “the wish to change the old with something new, but with its own…”. And he was ready to help “to transform the fundamentals of the Academy to something new, Russian, his own…”.

Unseldom the scientist had to overcome the hard periods of failures, misunderstanding and aloofness, arousing in him pessimism, tiredness and unbelief in his own strength. During one of such periods, in spring of 1884, he wrote a pathetic letter to the children from his first wife, Olga and Vladimir, a peculiar instruction for life, full of love to the children, and at the same time a will. The letter ended with the words: “… live with God, labour and truth. It’s time me had a rest, it’s time, farewell…”

By the twist of fate, rejected as a member of Petersburg Academy of Sciences, the scientist was unanimously elected at the beginning of the 1890’s as a member of the Russian Academy of Fine Arts.

D. I. Mendeleyev did a lot in the sphere of economy and industry of Russia.

He was always in earnest about agriculture and during a period he was making experiments at his plots in the estate of Boblovo. His niece N. Y. Kapustina-Gubkina wrote that during the first years after Dmitry Ivanovich had purchased the estate, he “took a great interest in his agricultural experiments.” There was fenced off a so-called experimental field with the samples of different fertilizer. The experiments gave a brilliant result. The peasants were amazed: the crop on the experimental field got above twice and three times the harvest on their fields. Kapustina-Gubkina remembered that once the peasants came to Dmitry Ivanovich with a question. After having finished the work, they couldn’t help asking about what had amazed them so much: “I say, Mitry Ivanych, your bread has grown so good over the Arzhany pond… Is it your talent or fortune?” The eyes of Dmitry Ivanovich flashed gaily and clearly, he grinned cunningly and said: “Certainly, brothers, the talent.” Sometimes he liked to talk to the peasants in their “vulgar manner”, and, according to the recollections of Kapustina-Gubkina, he did it very naturally, it suited very much “his Russian face.”

After some time the agricultural experiments in Boblovo were stopped because of the lack of time, but Mendeleyev applied to economic, agricultural and industrial problems of a larger scale.

Later he will say in his work “To the knowledge of Russia”: “In my life I had to take part in the fortune of three… affairs: oil, coal and iron-ore.” During the period of 1880–1883 he applied to chemistry, technology and economy of petroleum industry.

The scientist made the laboratory research on sublimation of petroleum at the Konstantinovsky factory of V. I. Ragozin near Yaroslavl. Under the observation of Mendeleyev at this factory there was made a special device, with the help of which the scientist was testing the organization of the continuous sublimation of petroleum.

While working in the “petroleum sphere”, Dmitry Ivanovich published the number of economical works. The main ideas, expressed in the economic works of this period (“The Letters about the factories”, etc.), come to the following. The industrialization of Russia at the present stage of its development is a historical necessity. The number of peculiarities of economic and geographical state of Russia – the underdeveloped natural resources, idle manpower or usable only seasonally, capacious home market of Russia itself and also of the neighbouring Asiatic countries, remoteness of many regions from the harbours and the rise in prices of imported hardware as a sequent of it – creates opportunities for developing the national industry.

D. I. Mendeleyev also studied the questions of economy of the coal industry. On the instructions of the government he studied the reasons of its crisis in the south of Russia. During winter and summer of 1888 Dmitry Ivanovich was in Donbas thrice, he learned the state of affairs at the main entrails, visited many mines and factories. He expounded the results of his trips in the number of official documents; he made reports at the meetings of Russian physico-mathematical society and broadly illustrated in a large publicistic article “The future power, resting on the shores of the Donetz.”

During the process of studying the industry of Donbas Dmitry Ivanovich came to a conclusion that the development of Russian industry was hampered by an incorrect correlation of the stuff export and the finished hardware import. After the trip to Donbas he started active work on the revision of the customs-tariff, into which he put many efforts. The result of it was the book “Perspicuous tariff, or the Research of the development of industry of Russia in connection with its general customs-tariff of 1891.”

In the book “Perspicuous tariff” the analysis of different systems of political economy is given, the customs policy of west-European countries is being examined, and first of all of England. A great importance is given to the history of the customs policy of Russia beginning from the 16th century.

The main idea of Mendeleyev – the use of industry – underlies his theoretical views. “Industry is a necessary link of the contemporary life of people at all steps of their development… It is necessary to put up with the participation and meaning of importance as with the structure of air and water, as with the necessity to live and die.” “If twinkling of the dawn of that future world and of the rightful allocation of prosperity, possible for countries and people, is visible ahead – just by means of the same industry, because the experience of history showed the inadequacy neither of the concentrated effort of the military power, of various forms of landed property nor of the highest development of enlightenment, especially since it is still drawing inspiration of the most pugnacious and reasoning classicists for reaching this gospel direction…”

At the same time D. I. Mendeleyev was seriously interested in the problems of aerostatics and meteorology. In summer of 1887 he made a famous flight on a balloon, organized by the Russian technical society. The flight took place during the solar eclipse. The scientist was attracted by the opportunity to observe the corona for the first time during this phenomenon.

Mendeleyev was preparing seriously this important experiment. He suggested, e. g. to use for flight a balloon, filled not with a coal gas, but with the hydrogen, which provided the raise to the big height and, therefore, guaranteed the success of the observation.

On August, 7th, in spite of the early morning-hour, an enormous crowd of people gathered at the place of start of the balloon, near Klin: scientists, close friends of Mendeleyev and just those, who wished to see this exciting show. It was supposed that Mendeleyev and pilot-aeronaut A. M. Kovanyko would fly. However, the balloon became wet because of the bad weather and appeared to be unable to raise two people. Mendeleyev flew alone. Mendeleyev wrote in his notes about the flight: “… however, I should explain the reason why I had an immediate determination to travel alone, when it turned out that the balloon wasn’t able to raise both of us… Understanding that we, professors, and scientists in general, are considered everywhere to be able to say and advise but not to be able to manage the practical work, that we, the Shchedrin’s generals, always need a peasant to do something otherwise we are all fingers and thumbs, – played a great role in my decision. I wanted to demonstrate that this view might be fair in some other cases, but unfair regarding the naturalists, who are passing their lives in their laboratories, at the excursions and in the research of nature in general. We should certainly be able to manage practice… and there was an excellent opportunity for it.”