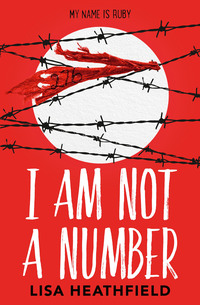

I Am Not a Number

‘Right,’ I turn to Lilli, my voice too bright. ‘Popcorn and a movie?’ She looks at me as though she’s waiting for the walls around us to crumble into dust. ‘They’ll be fine, Lils,’ I tell her over my shoulder as I walk into the kitchen. ‘They’ll be back before we know it.’

I get a message from Luke as soon as I open the cupboard.

Dad and I are going to the protest.

I’m not that surprised. His dad’s taken him on protest marches since before he could walk. But it makes me feel even more annoyed that Darren won’t let me go.

See you there, I text back before I even think about it.

You’re coming?

Yes. I’ll look out for you.

I close the cupboard and go into the sitting room. Lilli is already curled up on the sofa.

‘Change of plans,’ I say as casually as I can.

She looks up from her phone.

‘You don’t want to watch a film?’ she asks.

‘We’re going to the protest.’

‘We can’t.’

‘Of course we can. Our voice is important too.’

‘But Mum and Darren said we couldn’t.’

‘We’ll only go for a bit. If we’re back before them they won’t even know we were there.’

‘I could stay here on my own,’ Lilli suggests.

‘You know you can’t. It’s too late.’

‘Peggy’s next door. If anything happens I can call her.’

‘She’s like a hundred and fifty years old,’ I say. ‘She’s not going to be much good if you pour boiling water down yourself. Or flood the house or something.’

‘That’s stupid.’

‘It’s not. It could happen.’ I put out my hand to pull her up, but she stays sitting. ‘Please, Lils. I really want to go.’

‘What if the soldiers are there?’

‘They probably don’t even know it’s happening. But even if they are there, Mum says they won’t actually do anything.’ I walk into the hallway and hope she’ll follow. ‘Luke’s going to be there.’

Lilli appears within a second. I think she might love him almost as much as I do. ‘Is he allowed to go?’

‘He’s going with his dad.’

‘Will we see him?’

‘Hopefully.’

‘Okay,’ she says and already she’s looking for her shoes as I put on my coat. I try to ignore the doubt that’s pulling at me as she sits on the bottom stair to tie her laces.

‘Mum’ll kill you if she finds out you’ve taken me.’ Lilli’s spinning a bit from the excitement. This is a big deal for her as she never usually does anything she’s not meant to.

‘She’d kill me if I left you here.’

Lilli jumps up, grabs her coat and hooks her arm through mine. ‘Then you’re dead either way, aren’t you?’

As soon as we’re outside, I know it’s not a good idea. Our street seems strangely silent. One car drives past then turns the corner at the end. The lamplights are on even though it’s not completely dark.

‘Are you warm enough?’ I ask Lilli and she nods.

Most houses’ curtains are closed, but Bob Whittard’s are open and he’s sitting in his armchair, so I wave to him when he looks up. He doesn’t wave back. He doesn’t even smile. It feels like a hard line is being drawn down between those who support the government and those who are against it. Surely it’s something we can scrub out now, before it gets too deep?

As we get closer to the park there are more people about. They’re mostly as silent as we are as they scurry along towards Hebe Hill. There are soldiers too when I told Lilli there probably wouldn’t be any. One is standing at the end of Shaw Street, two more along Beck Avenue.

I hold Lilli’s hand tight as we take a shortcut through the alley. It’s darker in here and has a strange quiet, as though a lid has been put on the world. Ahead, there’s the entrance to the park and there are so many people, but I don’t know if seeing them all makes me feel safer, or more scared. I don’t recognise anyone, but the determination on their faces is all the same.

‘Have you texted Luke?’ Lilli asks.

‘I will when we’re in there.’ Although I’m not sure now how easy it’s going to be to find him.

We go through the park’s gate and have to follow everyone along the path. The flower beds either side are still filled with delphiniums, the first flowers Dad taught me to name. Seeing them makes me miss him, so I text to tell him that we’re here to protest against the Trads. I think he’ll be proud, but I know I won’t get a message back soon. I’ve learned the hard way not to wait for a reply.

From where we are we can see people covering the top of the hill. Someone is holding a megaphone, but their words aren’t clear enough yet. I feel better now that we’re here. I’m excited more than scared and I think Lilli is too, judging by her wide eyes and smile as she looks around.

‘Can you see Mum anywhere?’ I ask.

‘Shall we hide if we do?’

‘Perhaps.’ I know Mum would be angry, but maybe she’d be a little bit pleased that we’re protesting too.

There’s a crowd in front and behind us. I didn’t know there were so many Core supporters in our town. They’ve probably travelled in from a bit further away, but I’m surprised so many people want to show it. I wonder if some of them have come over to our side since the election? Since the government’s ideas have got crazier and crazier. I can’t imagine that everyone who voted for the Trads will be happy with restricted internet use and having their relationships monitored.

It’s almost single file again as we curve around the edge of the playground. I used to spend hours here, being pushed on the swing by Mum and Dad, then me pushing Lilli, then friends pushing each other and being told to leave. There’s no one there now. The swings aren’t moving, there are no shadows on the slide. Tomorrow there’ll be children laughing again, but for now we walk past with hardly a word.

There’s more space around us when we get to the hill. Hebe bushes are planted in random clumps for us to walk around. Their colour matches the purple of the Core symbol, so it seems that nature is on our side too. I reach out to touch the flowers. They look a bit like thistles, but they feel like feathers. If it was daytime there’d be tons of bees on them.

‘There are lots of people here,’ Lilli says, looking up at me.

‘How very perceptive of you, Chicken Bones,’ I say and she thumps me.

Three men are at the top and they must be standing on some sort of stage. They stick out above everyone. Two of them hold the purple Core Party flag, with its yellow steps going up the middle. The other has the loudspeaker and now we can hear his words. They rumble through the crowd in front of us and light a fire round my bones.

‘We won’t be forced into silence!’ the man shouts. ‘We won’t be ruled by bigots who love only to hate.’ The people around us are even louder now and I start to cheer with them. ‘We will champion your rights because each and every one of you has a right to free speech, a right to freedom of movement. A right to freedom!’

I’m glad we came here. It’s good to feel a part of this, to feel we might finally make a difference. That things really might change.

‘Our rights should be at the core of our society.’ His words thunder from him as people cheer again.

I look up into the sky. It’s a clear night and stars are beginning to reach out. Thousands and thousands of them watching, looking back at us. It makes me feel part of something even bigger.

‘We want to live in a tolerant country!’ The man’s words jump among us, landing on our hands, our ears, our skin. They skim up to the leaves and I imagine the wind picking them up and taking them to whisper in strangers’ ears. To let them see. Let them believe too. ‘A country that does not judge. Does not turn away those who cry for our help. We champion the rights of everyone, regardless of your class, your faith, your sexuality, your roots.’ The roar from the crowd is thick enough to touch. My arm stays in the air like everyone else’s. ‘It’s not a solution to cut down those who cry for help. Instead, we will listen. We will care. And we will rebuild our society from the foundation up. We won’t cease in our fight to champion the rights for everyone.’

‘Champions! Champions!’ My voice joins in with the chant, but Lilli stays silent, her arms by her side.

We’re getting pushed forwards. More people must be coming from the back.

‘Core Party for peace!’ the man with the loudspeaker calls above us all.

Suddenly we’re pushed so far forward that Lilli stumbles and I only just manage to pull her upright again. The crush is instant and people start to scream.

‘It’s okay,’ I tell Lilli. ‘They’ll make space.’ But it’s getting difficult to speak.

People scramble on to the stage and the man with the megaphone falls and disappears. And I see now, through gaps in the shoulders, that there are soldiers with plastic shields and they’re driving themselves into the protesters, forcing us together.

‘I can’t breathe,’ Lilli says, as more bodies press into us.

There’s yelling and it seems so distant as I lose my grip on Lilli’s hand. Everyone is pushing us, pushing everywhere, trying to run, but there’s nowhere to move. We’re all stuck and more people keep pounding into us and there’s nowhere for us to go.

My breath is being squeezed from me.

‘Get back,’ someone shouts. A woman beside me falls and I try to reach for her, but she’s sucked under and trampled on.

‘Lilli,’ I say, but the word is only a pinch of letters.

Mum. Luke.

My sister has tears in her eyes, but I can’t hear her crying.

We’re heaved forwards, my feet barely on the ground. My lungs are being crushed and there’s not enough air.

I see Lilli lifted, pulled up. A man grabbing her with one arm, pushing her over the heads of others.

‘Ruby!’ she screams, but I can’t see her. My eyes hurt. How can there be so much air above us, just out of reach?

We move forwards. I trip over something soft, but the pressure of the bodies around me keeps me upright. People are shouting, desperate. Get back. Make space.

We move as a dying animal, down the side of the playground as people pile over the fence, stumbling and falling. There’s screaming as we spill forwards until there’s space, enough air now.

‘Lilli.’ My voice is too quiet. Yet my breathing is easier, just splinters in my lungs now. ‘Lilli!’ I don’t want to be crying, but everywhere there are people shouting and none of them are my sister. The man lifted her up and she’s gone.

I’m being pushed further along and I look up as a soldier raises his baton and he brings it down on a man. I hear him hit him, a deadening thump on bones and I know I have to get away from here. But I can’t get through, because people are fighting back, charging into the soldiers. I’m stumbling over crushed banners and there’s nowhere to hide. And everywhere there are the distorted faces of the soldiers behind their transparent shields. Just their eyes through their helmets and they raise batons and they strike out and I’m too close as panic burns my chest.

Someone in front of me falls, clutching his eyes. A soldier has a spray and I see him grab a woman by her coat and she begs as he holds the can close to her skin. And so I run. Past stumbling bodies, through a cloud of terror, wading through cries I’ve never heard. I’m at the fence with others and we’re clambering over it, someone helping me so I don’t fall.

I make it to the alleyway, but I’ve left my sister behind and my phone is ringing and it’s my hands that take it from my pocket and my mum’s voice is shouting and I tell her that I don’t know where Lilli is. Terror seeps from me into the wall at my back.

‘Lilli’s here,’ I hear my mum say.

She’s at home.

I run, the phone in my hand, through the streets I thought I knew, past houses with doors closed to me. I see someone running towards me and I know it’s Darren and he reaches me and hugs me so tight.

‘You’re safe,’ he says and I don’t know whether it’s my lungs, my heart, or my head that hurts as he pulls me towards our home. Where my mum is standing in the doorway and she holds me before I’m even inside and when our front door shuts behind us the relief to be safe is bright.

‘Jesus, Ruby,’ Darren is shouting.

‘You said the protest would be okay.’ I can’t make sense of the words I want to say.

‘I never said that.’

‘This isn’t helping,’ Mum says. ‘They’re back now.’

‘Where’s Lilli?’ I ask.

‘In the sitting room,’ Mum tells me.

‘She thought she was going to die, Ruby,’ Darren says.

‘But they’re both safe,’ Mum glares at him. ‘That’s the most important thing.’

‘We could have lost them.’ Darren’s voice is still too loud. ‘You saw it there, Kelly. You saw what those Trads did. They took a peaceful protest and they turned it into a deathtrap.’

‘I’m not going to have this discussion now.’ Mum goes into the sitting room and I’m left with Darren in front of me, his anger sharp.

‘The soldiers were hitting people,’ I tell him. ‘But we hadn’t done anything wrong.’ He steps forward to hug me, but I won’t let him. Sirens call in the distance. ‘Why did they do it?’

‘I don’t know,’ is all he answers.

CHAPTER THREE

‘You told us that you’d had enough and we listened. Enough of broken families. Enough of soaring crime rates blighting our country. Enough of our people hungering for jobs.’ – John Andrews, leader of the Traditional Party

I’m awake before my alarm clock and watch the sun start as a square of light in the corner of my ceiling, until it spreads across my room. I hold out my hands and stretch my fingers as far as they can go and then count them, slowly, feeling the sound of each number on my tongue.

I breathe in until I can’t any more. Hold my breath. Hold it. Hold it. And imagine what it’d be like to not be able to let it out. My lungs would be crushed until I close my eyes and drift away.

The door opens and I gasp for air.

‘Darren doesn’t want us to go to school,’ Lilli says. She walks across my room, lifts the corner of the duvet and gets into bed. I shuffle closer to the wall, but still her feet are cold against my legs. She sleeps with them outside her duvet. She likes to face the bogeyman straight on. ‘But Mum says we have to go.’

I lean over her to turn on my phone.

‘What do you want to do?’ I ask her.

‘Stay here. But Mum says we can’t.’

On cue, the door opens and Mum comes in, the purple band clear on her arm.

‘Up you get,’ she says, opening the curtains so roughly I’m surprised she doesn’t pull them down. ‘You can’t be late.’ As though everything is normal. That life hasn’t just spun away into a black hole.

‘Lilli doesn’t want to go,’ I say.

‘There are a lot of things none of us want to do,’ Mum says. ‘But we have to.’ She’s sorting through the pile of clothes on my chair, finding my school clothes. ‘This could’ve done with a wash.’ She holds up my sweatshirt.

‘Are you going to work?’ I ask. Lilli and I don’t move from the comfort of my bed.

‘Of course. It’s an ordinary day, Ruby.’

‘How can it be?’

‘It has to be,’ she tells me.

My phone beeps, but Mum grabs it before I have a chance.

‘I’ll take this downstairs. You can have it when you’re dressed,’ she says and she’s out of the room before I can challenge her.

‘Just for the record,’ Darren says. ‘I don’t think any of you should go.’ He’s standing next to the fridge, both hands round his mug of coffee.

‘You’re not helping,’ Mum says, as she grabs her car keys from the side.

‘And you’re not thinking straight, Kelly,’ Darren tells her. Mum stops and stares at him.

‘The only people not thinking straight are those bloody Trads, Darren. If you want to take out your frustration on anyone, take it out on them.’

‘And get a bullet through my head for my trouble?’ Darren’s words snap out of him and make everything go still.

‘So we just crawl into our holes like they want us to?’ Mum says. ‘Don’t go to work, don’t go to school, just stay in our homes and wither away until they completely destroy our country? Is that what we should do?’

‘I don’t know any more,’ Darren says.

‘Well, I do,’ Mum says, wrapping her scarf round her neck. ‘School is the safest place for them.’

‘How do you figure that out?’ I haven’t seen Darren look this furious in ages.

‘The Trads are going to be on their best behaviour after last night,’ Mum says. ‘They may have managed to twist the truth about the protest, but they’ll be hard pushed to keep people on their side if they hurt kids in a school.’

Darren visibly winces.

‘What do you want to do, Ruby?’ he asks me.

I look at them both standing there and memories of the protest whittle dread into me. But I know I’ll be frightened anywhere.

‘I want to go,’ I say. Maybe Mum’s right and we’ll be safer there. Or perhaps I’ve just conditioned myself to say the opposite to Darren.

‘That’s sorted then,’ Mum says, as she storms out of the room and I follow her. Darren comes into the hallway.

‘At least let me drive you and Lilli there,’ he says to me.

‘If you have to,’ I say.

Mum grabs her bag from the hall table before she opens the front door. Something makes her stop still.

‘What is it?’ Darren pulls the door wide open. Someone has painted a giant C across the wood, going from the top all the way to the bottom.

‘Who’s done that?’ Lilli asks.

Mum shakes her head in that way she does when she’s trying to be strong.

‘I’d hazard a guess it’ll be the Traditionals,’ she says.

‘Why on our door?’

‘I bet it’ll be on the door of every Core household,’ Darren says.

‘I don’t want to go to school,’ Lilli says quietly.

‘You don’t have to,’ Darren says before Mum can speak. ‘I’ll stay here with you.’

Mum nods. ‘Okay,’ she says, less determined now.

‘Ruby?’ Darren looks at me. Part of me wants to stay here with Lilli, to stay safe behind the walls of our home where no one can touch us, where I don’t have to wear this stupid purple band for everyone to see. But Mum is going to work. And I want to see Luke.

‘I’m still going to school.’ I need something to distract me from the nightmare our country seems to have stumbled into.

‘Could we clean the paint away later?’ Lilli asks Darren.

‘I doubt they’ve made it that easy for us,’ Mum says as she steps outside.

I’ve never known our school to feel like this, as though even the walls are watching and judging. And there’s a strange link between all of us wearing Core bands. People I’ve never spoken to before smile and nod at me in the corridor. And people who I thought were vague friends look away.

Never before in my life has it been awkward between Sara and me. But now a strange, invisible wall has been stacked up between us.

‘Hey,’ I say.

‘Hey.’

And that’s it. The scariest thing in my life happened to me yesterday, but I can’t even talk to her about it. She should be the first person I want to tell about the protest. She’d be able to put it right somehow, find a way to even laugh today, but she seems distant. I can’t tell if it’s because she doesn’t want to know, or is scared to ask if I was there.

‘Did your parents tell you not to talk to me?’ I ask, attempting a smile.

‘No.’ She shakes her head.

Mr Hart comes in late, his purple band strapped to the outside of his jacket. He doesn’t have to tell us to be quiet. We already are. He’s halfway through the register when James puts up his arm, a green band clear to see.

‘Sir,’ he says. ‘Doesn’t what happened last night prove something?’

‘And what exactly is that, James?’ Mr Hart’s expression is cold. If he wasn’t a teacher I think he might thump him.

‘That the Cores are out of control and violent. That if they came into power it’d be a joke.’

Violent? It was a peaceful protest until the Trad soldiers waded in.

‘I don’t find anything to laugh about,’ Mr Hart says, ‘when people have ended up seriously injured.’

‘All through faults of their own,’ James says.

We weren’t at fault. We were only there protesting – doing nothing else.

‘So you believe everything you read on the internet, do you?’ Mr Hart says.

‘Those riots were real. There’s no way they were staged by the Trads.’

‘From what I understand, they doctored the footage,’ Mr Hart says.

‘Doctored?’ Ashwar asks.

‘Edited it,’ Mr Hart tells her. ‘The news only showed a half truth. Probably not even that.’

‘They’re not going to broadcast a blatant lie,’ Ashwar says.

‘Aren’t they?’ Mr Hart glares at her. ‘You’ve all heard enough about fake news.’

‘I know what happened,’ I say. ‘Because I was there.’ I feel every single person in the classroom turn to look at me. My skin blazes red.

‘The Cores faked those images,’ someone shouts from the back.

‘They didn’t.’ My voice is shaking. I don’t want to remember, I don’t want to ever be there again, but I have to let them know the truth. ‘Everyone was calm, but then the soldiers started attacking us.’

‘You provoked them,’ James says.

‘We didn’t,’ I say, feeling stronger now. ‘There wasn’t a riot or anything. The Trads started it and we were crushed.’

James claps his hands slowly. ‘Nice one, Westy. You’re pretty good at twisting real events.’

‘That’s enough,’ Mr Hart says.

‘Oh, so now you’re trying to silence the truth?’ James says. ‘I’m simply pointing out the lies, but you won’t let me have my say?’

‘What I won’t let,’ Mr Hart says, anger spinning around him, ‘is a bully stay in my class.’

‘Are you sending me out for voicing an opinion?’ James smirks. ‘An opinion that is, in fact, the truth?’

‘I’m simply giving you a warning.’

‘I wonder what the Trads would think if they found out a teacher was calling them liars, sir,’ James continues. ‘That you’re accusing them of editing footage of the protests. I reckon they’d be quite interested to know.’

‘This conversation is ending right now,’ Mr Hart tells him. ‘I’ve a register to finish.’ He’s trying to stay calm, but his jaw is tense. I think his hands are shaking too. ‘Jermain,’ he says, glancing up.

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Lucy.’

‘Yes.’

Sara nudges my arm. ‘Were you really there?’ she whispers.

‘Yes.’

‘Was it frightening?’

‘Yes.’ I can see the real Sara in her eyes. The worry for me, the confusion. ‘Can we hang out at break?’ I ask. ‘We could go to the oak tree?’

She doesn’t smile, but at least she nods.

‘I think what James has forgotten to point out, sir,’ Ashwar says, as soon as the register is finished. ‘Is that the Core supporters started riots this morning too and they got completely out of control.’

‘They were a direct response,’ Mr Hart says, ‘to the unprovoked attack of citizens last night.’

‘It was self protection,’ Ashwar says.

‘The Trads weren’t under any threat,’ I say. But it’s barely loud enough for anyone to hear.

‘What I don’t understand, Ashwar,’ Conor says. ‘Is how come your family vote for them?’ He’s swinging back on his chair, but Mr Hart doesn’t pick him up on it. ‘You’re Muslim, right?’

‘None of this is about religion.’ Ashwar’s eyes are steel on him.

‘No. But some of it’s about race,’ Conor says. ‘By tightening the borders, they’re basically saying they only want Brits living here. If they’d done that before your parents or grandparents or whoever arrived here you wouldn’t have been allowed in.’ Conor lands the front legs of his chair heavily on the ground. ‘How can that be okay?’

‘I don’t have to agree with everything they stand for,’ Ashwar says.

‘But it’s a pretty major thing,’ Conor carries on. Mr Hart watches from the front of the classroom. His arms are crossed, but his Core band is still showing.