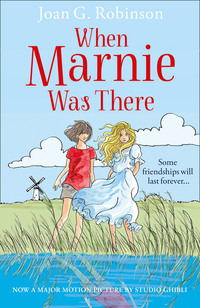

When Marnie Was There

There was a salty smell in the air, and from the marsh on the far side of the water came the cries of seabirds. Several small boats were lying at anchor, bumping gently as the tide turned. In that short distance she seemed to have come on another world. A remote, quiet world where there were only boats and birds and water, and an enormous sky.

She jumped at the sudden sound of children’s voices. There was laughter, and shouts of, “Come on! They’re waiting!” and a group of children appeared round the corner of the staithe. Five or six boys and girls of different ages in navy blue jeans and jerseys. Immediately Anna drew herself up stiffly and put on her ‘ordinary’ face.

But it was all right, they were not coming her way. They ran, shouting and jostling each other to a car drawn up at the end of the road, and climbed in. Then the doors slammed, the car reversed, and as it drove past her up to the crossroads she had a glimpse of a man at the wheel, a woman beside him, and the children all bobbing about in the back, talking excitedly.

It was very quiet when they had gone.

“I’m glad,” she said to herself. “I’m glad they’ve gone.

I’ve met enough new people for one day.” But the feeling of freedom had changed imperceptibly to one of loneliness. She knew that even if she had met them they would never have been friends. They were children who were ‘inside’ – anyone could see that. Anyway, I don’t want to meet any more people today, she repeated to herself-hardly realising that Mr and Mrs Pegg were the only people she had spoken to since she left London.

And that had been only this morning! Already the turmoil of Liverpool Street Station, the hurry, the confusion, the nearness of parting – against which she had only been able to protect herself with her wooden face – seemed a hundred years ago, she thought.

She listened to the water lapping against the sides of the boats with a gentle slap-slapping sound, and wondered who the boats belonged to. Lucky people, she supposed. Families who came to Little Overton for their holidays year after year and weren’t just sent here to be got out of the way, or because of not-even-trying, or because people “didn’t quite know what they were going to do with them”… Boys and girls in navy blue jeans and jerseys, like that family…

She walked down to the water’s edge, took off her shoes and socks, and stood with her feet in the water, staring out across the marsh. On the horizon lay a line of sandhills, golden where the sun just caught them, and on either side the blue line of the sea. A small bird flew over the creek, quite close to her head, uttering a short plaintive cry four or five times running, all on one note. It sounded like “Pity me! Oh, pity me!”

She stood there looking and listening and thinking about nothing, drinking in the great quiet emptiness of marsh and water and sky, which now seemed to match her own small emptiness inside. Then she turned quickly and looked behind her. She had an odd feeling suddenly that she was being watched.

But there was no-one to be seen. There was no-one on the staithe, nor on the high grassy bank that ran along to the corner of the road. The one or two cottages appeared to be empty, and the door of the boathouse was shut. To the right the village straggled away into fields, and in the distance a windmill stood alone, silhouetted against the sky.

She turned and looked away to the left. Beyond the few cottages a long brick wall ran along the grassy bank, ending in a clump of dark trees.

And then she saw the house…

As soon as she saw it Anna knew that this was what she had been looking for. The house, which faced straight on to the creek, was large and old and square, its many small windows framed in faded blue woodwork. No wonder she had felt she was being watched with all those windows staring at her!

This was no ordinary house, in a long road, like the one she lived in at home. This house stood alone, and had a quiet, mellow, everlasting look, as if it had been there so long, watching the tide rise and fall, and rise and fall again, that it had forgotten the busyness of life going on ashore behind it, and had sunk into a quiet dream. A dream of summer holidays, and sandshoes littered about the ground-floor rooms, dried strips of seaweed still flapping from an upper window where some child had hung them as a weather indicator, and shrimping nets in the hall, and small buckets, a dried starfish swept into a corner, an old sun hat…

All these things Anna sensed as she stood staring at the house. And yet none of them had she ever known. Or had she…? Once, when she was in the Home, she had been to the seaside with all the other children, but she hardly remembered that. And twice she and the Prestons had been to Bournemouth and walked along the promenade and sat in the flower gardens. They had bathed too, and sat in deck chairs, and been to the concert party at nights.

But this was different. Here there was none of the gay life of Bournemouth. It was as if the old house had found itself one day on the staithe at Little Overton, looked across at the stretch of water with the marsh behind, and the sea beyond that, and had settled down on the bank, saying, “I like this place. I shall stay here for ever.” That was how it looked, Anna thought, gazing at it with a sort of longing. Safe and everlasting.

She paddled along in the water until she was directly opposite to it, and stood, looking and looking… The windows were dark and uncurtained. One of the upper ones was open but no-one was looking out. And yet it seemed to Anna almost as if the house had been expecting her, watching her, waiting for her to turn round and recognise it. And in some way she did.

As she stood there, half dreaming in the water a few feet from the shore, the strange feeling crept over her that this had all happened before. It would have been difficult to explain even what she meant by this, but it was almost as if she were now standing outside of herself, somewhere farther back, watching herself standing there in the water – a small figure in her best blue dress with her socks and shoes in her hand, looking across the staithe at the old house with many windows. She even noticed without concern that the water must have risen slightly, because she could see it lapping at the hem of her dress, making a dark stain round the very edge.

Then the little grey-brown bird flew overhead again, crying, “Pity me! Oh, pity me!” and Anna shook herself out of her dream… She looked down and saw that the water had come up to her knees while she had been standing there. It had even reached the hem of her dress…

“Who lives in the big house by the water?” she asked Mrs Pegg, as they sat drinking cocoa in the kitchen later.

“The big house by the water?” said Mrs Pegg vaguely. “Now which one would that be?”

“The one with blue windows.”

Mrs Pegg turned to Sam, who was eating bread and cheese, spearing pickled onions on the end of his knife and putting them whole into his mouth. “Who lives in the big house with the blue windows, Sam?”

Mr Pegg looked equally vague. He thought for a moment, then said, “Oh, ah, you mean The Marsh House? I don’t know as anyone lives there, do they, Susan?”

Mrs Pegg shook her head. “Not as I know of, but I never go down by the staithe so I wouldn’t know. Didn’t I hear it was going to be bought by a London gentleman? I think Miss Manders at Post Office said so. ‘That’ll need a fair lot of doing up,’ she said. ‘It’s been empty quite a while.’ But maybe that’s not the one.”

“And who are the children in navy blue jeans and jerseys?” asked Anna. “The big family?”

Again Mrs Pegg looked puzzled. “I don’t know of none,” she said. “In the summer holidays there’s lots of children, of course, in their holiday clothes like that. But I don’t know of none now, do you, Sam?”

Mr Pegg shook his head. “Maybe they was just down for the day,” he suggested helpfully.

“Yes, perhaps,” said Anna, remembering the car. But she was secretly disappointed. In her own mind she had already decided that the house by the water was theirs. They had looked the right sort of family to live in a house like that.

“Anything else you’d like to know?” asked Mr Pegg, smiling.

“Yes,” said Anna. “Which is the bird that says, ‘Pity me! Oh, pity me!’”

Mrs Pegg gave her an odd look. “Time you was in bed, my lass,” she said briskly. “It’s been a long day, what with the journey and all. Come you on up and I’ll get you settled in.” She pulled herself out of her chair and carried the cups into the scullery to put them in the sink.

Anna got up and stood looking down at Mr Pegg still eating his bread and cheese. “Goodnight, then,” she said.

“Ah, goodnight, my biddy!” he said abstractedly. “I’m thinking – might that be a sandpiper, do you think? That makes a lonesome little cry, that does. Though I can’t say I ever heared the words afore!” he added with a chuckle.

Chapter Four

THE OLD HOUSE

ANNA THOUGHT OF the house as soon as she awoke next morning. In fact she must have been thinking about it even before she awoke, because by the time she opened her eyes and saw the white, sloping ceiling of her little room, and smelt the old, sweet, warm smell of the cottage, she was saying to herself – still half asleep – “I must hurry It’s waiting for me.” Then she realised where she was.

Thank goodness the journey to Norfolk was over! She must have been dreading it more than she had realised. It had been an unknown adventure looming up ahead, and all her life at home during the past few weeks had been a preparation for it. Now it was over. She was here. And as soon as she could she would go down to the creek again and see the house.

At breakfast Mrs Pegg said, “How about coming into Barnham with me on the bus? I usually goes once a week to the shops, and it would make something for you, wouldn’t it, lass?”

Anna looked doubtful.

“Or maybe you’d like to play with young Sandra-up-at-the-Corner?” Mrs Pegg suggested. “She’s a well behaved, nicely-spoken little lass. I know her mum and I could take you up there.”

Anna looked more doubtful still.

Had she noticed the windmill yesterday, Sam asked. It was a fair way off, and not much to look at when you got there, but that might make something too.

Mrs Pegg rounded on him. That would do nothing of the sort, she said. It was too far for the lass on her own and all along the main road into the bargain.

“Oh, ah, so it is!” said Sam. “Never mind, my biddy. Maybe I’ll take you there myself one day.”

Anna said she did not mind at all, she was quite all right doing nothing. “Really I like doing nothing better than anything else,” she explained earnestly. They both laughed at this, but Anna, determined to be taken seriously, stared hard at the tablecloth, looking as ordinary as she knew how.

“I don’t know that I can do with you sitting around in the kitchen all day, my duck,” Mrs Pegg said doubtfully. “What with the cleaning and the cooking and the washing and Sam being under my feet half the time as it is—”

Anna interrupted. “Oh, no! I meant outside. Can I go down to the creek?”

Mrs Pegg looked relieved. She had been afraid Anna might have wanted to spend the day in the front room, the door of which was always kept closed except on special occasions. Yes, of course Anna could go down to the creek. Or if the tide was out she could walk over the marsh to the beach, and if it was high she could always go down in Wuntermenny’s boat. “As long as you don’t mind not having no company,” she said. Anna assured her she did not mind.

“And just as well, if you go down in the boat with Wuntermenny West,” said Sam. “He can’t abide having to talk.” He stirred his tea ponderously with the handle of his fork and looked hopefully across the table at her. “No doubt you’re thinking that’s a queer name, eh?” he said, smiling.

Anna had not thought about it but said, “Yes,” politely.

“Ah! I’ll tell you how it was, then, since you’re asking,” said Sam. “Wuntermenny’s ma – old Mrs West, that was – she had ten already when he was born. ‘What’re you going to call him, mam?’ they all says, and she says, tired-like, ‘Lord knows! He’m one-too-many and that’s a fact.’ So that’s how it was!” he said, laughing and spluttering into his mug of tea. “And Wuntermenny West he’s been ever since.”

As soon as she could get away, Anna ran down to the staithe. The tide was out and the creek had dwindled to a mere stream. At first she was disappointed when she saw the old house again. It seemed to have lost some of its magic, now that it only looked out on to a littered foreshore instead of a wide stretch of water. But even as she looked, she saw that it was still the same quiet, friendly-faced house. She felt rather as if she had come to visit an old friend, and found that friend asleep.

She scrambled up the bank, clinging on to tufts of grass, and walked slowly along the footpath in front of the house, looking sideways into the windows. She was not sure if she was trespassing, and it was difficult to see clearly without stopping and pressing her face up close against the glass. Suppose someone should be watching, from inside! More than ever now she had the feeling she was spying on someone who was asleep. She moved nearer and saw only her own face staring back at her, pale and wide-eyed.

The Peggs were right, she thought. No-one was living in the house. Nevertheless, it still had a faintly lived-in look, more as if it were waiting for its people to return, than having been deserted. She grew bolder and looked through the narrow side windows on either side of the front door. There was a lamp on a windowsill, and a torn shrimping net was leaning up against the wall. She saw that a wide central staircase went up from the middle of the hall.

That was all there was to see. She slid down the bank again, waded across the creek, and sat for a long time with her chin in her hands, staring across at the house, and thinking about nothing. If Mrs Preston had known she would have been even more worried than she had been, but at the moment she was more than a hundred miles away, pushing a wire trolley round the supermarket. She had forgotten that in a place like Little Overton you can think about nothing all day long without anyone noticing.

Anna did go down to the beach in Wuntermenny’s boat. She found him as unsociable as the Peggs had promised. He was small and bent, with a thin, lined face, and eyes which seemed to be permanently screwed up against the light, looking into the far distance. After the first grunt of recognition he hardly noticed her, so she was able to sit up in the bow of the boat, looking ahead, and ignore him too. This suited her well, but it made her feel lonelier, and she was a little frightened that first afternoon. There seemed such a huge expanse of water and sky, and so little of herself.

Sitting alone on the shore, while Wuntermenny in the far distance was digging for bait, she looked back at the long, low line of the village and tried to pick out The Marsh House. But it was not there! She could see the boathouse, and the white cottage at the corner, and farther away still she could see the windmill. But along where The Marsh House should have been there was only a bluish-grey smudge of trees.

Alarmed, she stood up. It had to be there. If it was not, then nothing seemed safe any more… nothing made sense… She blinked, opened her eyes wider, and looked again. Still it was not there. She sat down then – with the most ordinary face in the world, to show she was quite independent and not frightened at all – and with her knees up to her chin, and her arms round her knees, made herself into as small and tight a parcel as she could, until Wuntermenny came trudging up the beach with his fork and his bucket of bait.

“Cold?” he grunted, when he saw her.

“No.”

She followed him down to the boat, and those were the only two words that passed between them all the afternoon. But as they rounded a bend in the creek and she saw the old house gradually emerge from its dark background of trees, she felt so hot and happy with relief that she nearly said, “There it is!” out loud. She realised now that it had been there all the time. In the distance the old brick and blue-painted woodwork had merely merged into the blue-green of the thick garden trees. She realised something else, too. As they passed close under the windows, on the high tide, she saw that the house was no longer asleep. Again it had a watching, waiting look, and again she had the feeling it had recognised her and was glad she was coming back.

“Enjoy yourself?” asked Mrs Pegg, who was frying sausages and onions in the scullery when Anna returned.

Anna nodded.

“That’s right, my duck. You do what you like. Just suit yourself and follow your fancy.”

“And maybe I’ll take you along to the windmill one day if you’re a good lass,” said Sam.

Chapter Five

ANNA FOLLOWS HER FANCY

SO THAT WAS how it was. Anna suited herself and went where she liked. In a way, now, she had three different worlds in Little Overton. The world of the Peggs’ cottage, small and warm and cosy. The world of the staithe, where the boats swung at anchor in the creek and The Marsh House watched for her out of its many windows. And the world of the beach, where great gulls swooped overhead and she sometimes found rabbit burrows in the sand dunes, and the bones of porpoises lying in the fine, white sand. Three separate worlds… but in her own mind the important one was the staithe with the old house by the water.

Gradually, instead of thinking about nothing, she thought about The Marsh House nearly all the time; imagining the family who would live there, what it was like inside, and how it would look in the evenings, in autumn, with the curtains drawn and a big fire blazing in the hearth.

Trudging home across the marsh at sunset one evening she saw the windows all lit up and ran, thinking they must have arrived while she was down at the beach. Perhaps if she hurried she might catch sight of them – the family of children in navy blue jeans and jerseys – before the curtains were pulled. But as she drew nearer she saw that she was wrong. There were no lights in the house. It had only been the reflection of the sunset in the windows.

On another day she saw – or thought she saw – a face pressed close to the window; a girl’s face with long, fair hair hanging down on either side – watching. Then it disappeared. Even when there was clearly no-one there, she still had this curious feeling of being watched. She grew used to it.

The Peggs were glad she had settled down so well. It was good for the lass to be out of doors so much, and provided she came in to meals at reasonable hours, and ate heartily, they saw nothing to worry about. She was, in fact, “no trouble at all,” as Mrs Pegg assured Miss Manders at the Post Office.

A letter came from Mrs Preston in answer to Anna’s card. She was glad Anna was happy, and yes she could wear the shorts every day as long as Mrs Pegg didn’t mind. We’re looking forward so much to hearing all the interesting things you’re doing, she wrote, but if you haven’t time for a long letter, a card will do. Enclosed was a small folded note with “Burn this” written across the outside, and inside, Does the house really smell, dear? Tell me what sort of smell.

Anna, who had quite forgotten her remark about the cottage smelling different from home, wondered vaguely what it meant, burnt the note obediently, and forgot about it. She bought a postcard with a picture of a kitten in a flower pot on it, and wrote on the back, I’m sorry I didn’t write before but I forgot, and on Thursday the Post Office was shut so I couldn’t buy this card. I hope you like it. There was only room for one more line, so she put, I went to the beach. Love from Anna. She added two Xs for good measure, and posted it, well satisfied, never dreaming Mrs Preston might be disappointed at having so little news.

One day Sandra-up-at-the-Corner came to the cottage with her mother. Dinner was late that day, so Anna was caught before she had time to slip out of the scullery door.

Sandra was fair and solid. Her dress was too short and her knees were too fat, and she had nothing to say. Anna spent a wretched afternoon playing cards with her at the kitchen table, while Mrs Pegg and Sandra’s mother sat and talked in the front room. Sandra and Anna knew different versions of every game, Sandra cheated, and they had nothing to talk about.

In the end Anna pushed all her cards over to Sandra’s side and said, “Here you are. Keep them all, then you’ll be sure to win.”

Sandra said, “Ooh, that I never!” went bright pink and relapsed into sulks in the rocking chair. She spent the rest of the afternoon examining the lace edge of her nylon petticoat, and trying to twist her straight, straw-coloured hair into ringlets. Anna read Mrs Pegg’s Home Words in a corner and was thankful when they went.

After that she was less trouble than ever, and stayed out all day in case she might ever have to play with Sandra again.

One afternoon, coming back from the beach where Wuntermenny had been collecting driftwood, and she had been looking for shells, Wuntermenny astonished her by saying his first complete sentence. They were coming up towards the staithe when he suddenly jerked his head over his shoulder and said in a gruff, casual voice, “Reckon they’ll be down soon.”

Anna sat up in surprise. “Who will?”

Wuntermenny jerked his head again, over towards the shore. “Them as’ve took The Marsh House.”

“Will they? When? Who are they?”

Wuntermenny gave her a look of deep, pitying scorn and shut his mouth tightly. Too late she realised her mistake. She had been too eager, asked too many questions. If she had just looked sleepily uninterested he would probably have told her all she wanted to know. Never mind, she would soon find out. She might even ask the Peggs.

But on second thoughts she decided not. They might think she wanted to make friends with the people, and that was not what she wanted at all. She wanted to know about them, not to know them. She wanted to discover, gradually, what their names were, choose which one she thought she might like best, guess what sort of games they played, even what they had for supper and what time they went to bed.

If she really got to know them, and they her, all that would be spoiled. They would be like all the others then – only half friendly. They, from inside, looking curiously at her, outside – expecting her to like what they liked, have what they had, do what they did. And when they found she didn’t, hadn’t, couldn’t – or what ever it was that always cut her off from the rest – they would lose interest. If they then hated her it would have been better. But nobody did. They just lost interest, quite politely. So then she had to hate them. Not furiously, but coldly – looking ordinary all the time.

But this family would be different. For one thing they would be living in ‘her’ house. That in itself set them apart. They would be like her family, almost – so long as she was careful never to get to know them.