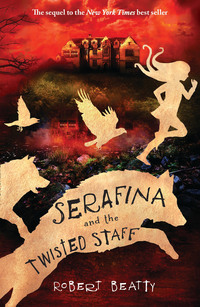

The Serafina Series

When she didn’t hear anyone shout, Hey, there’s a peculiar girl in the grass over there! she crawled over to the base of a nearby tree and peeked out.

A tall girl about fourteen years old with long, curly red hair stood waiting for Braeden to adjust the stirrup on her horse’s sidesaddle. She wore a fitted emerald-green velvet riding jacket with an upturned collar, triangular lapels and turned-back cuffs. The jacket’s gold buttons glinted in the sunlight whenever she turned her body or lifted her wrist. Her trim green-and-white-striped waistcoat and long skirt matched her jacket in every detail.

Serafina frowned in irritation. Braeden normally rode alone. His aunt and uncle must have asked him to entertain this young guest. But what should she do now? Should she brush off her ripped, dirtied, bloodstained, fang-shredded dress, and walk over to Braeden and the girl and introduce herself ? She imagined an exaggerated, backwoods version of herself coming out of the brush towards them. ‘Mornin’, y’all. I’m just back from catchin’ some wood rats and nearly gettin’ eaten up by a pack of wolfhounds. How you two doin’ this mornin’?’

She thought about approaching them, but maybe interrupting Braeden and the girl would be a rude, unwelcome imposition.

She had no idea.

Out of instinct more than anything else, she stayed hidden where she was and watched.

The girl allowed Braeden to help her up into the saddle, then rearranged her legs and the long folds of her riding skirt to drape over the left side of the horse. That was when Serafina noticed that she was wearing beautiful dove-grey suede, laced-up, flower-embroidered ankle boots. They were completely ridiculous for horseback riding, and Serafina couldn’t even imagine running through the forest in such delicate things, but they sure were pretty.

Along with her fancy attire, the girl carried a finely made riding cane with a silver topper and a leather whip end. Serafina smirked a little. It seemed like all the fancy folk liked to carry some sort of cane or walking stick or other accoutrement whenever they went outside, but she preferred to have her hands free at all times.

Seeing the whip, Braeden said, ‘You won’t need anything like that.’

‘But it goes with my outfit!’ the girl insisted.

‘If you say so,’ Braeden said. ‘But please don’t touch the horse with it.’

‘Very well,’ the girl agreed. She spoke in a grand and mannerly tone, as if she’d been raised in the way of a proper lady and she wanted people to know it. And Serafina noticed that she had an accent like Mrs King, Biltmore’s head housekeeper, who was from England.

‘So, do tell,’ the girl said. ‘How do I stop this beast if it runs away with me?’

Serafina chuckled at the thought of the horse bolting with the screaming, frilly-dressed girl, jumping a few fences in wild abandon and then landing in a mud pit with a glorious splat.

‘You just need to pull back on the reins a little bit,’ Braeden said politely. It was clear that he didn’t know this girl too well, which further reinforced Serafina’s theory that Braeden’s aunt and uncle were putting him up to this.

Beyond all the girl’s fanciness and airs, there was something that bothered Serafina about her. A highfalutin fashion plate like her would certainly know how to ride a horse, but she seemed to be pretending that she didn’t. Why would she do that? Why would she feign helplessness? Was that what a girl did to attract a boy’s attention?

Seemingly unmoved by the girl’s ploy, Braeden walked over to his horse without further comment. He slipped effortlessly onto his horse’s bare back. A week ago, he had explained to Serafina that he didn’t use a bridle and reins to control his horse but signalled the speed and direction he wanted to go by adjusting the pressure and angle of his legs.

‘Now, we mustn’t go too fast,’ the girl said daintily as the two young riders rode their horses at a walk out onto the grounds of the estate. Serafina could tell she wasn’t scared of the horse but simply pretending to be a delicate soul.

‘Actually, I thought we might do a bit of high-speed racing,’ Braeden said facetiously.

Seeming to realise that Braeden wasn’t falling for her precious-princess routine, the English girl changed her tone as fast as a rattlesnake changes the direction of its coiling path.

‘I would race you,’ she replied haughtily, ‘but I might get a speck of mud on my skirt from my horse kicking up dirt into your face as I passed you.’

Braeden laughed, and Serafina couldn’t help but smile as well. The girl had a bit of spunk in her after all!

As Braeden and the girl rode away down the path, Serafina could hear them talking pleasantly to each other, Braeden telling her about his horses and his dog, Gidean, and the girl listing the particulars of the gown she’d be wearing to dinner that evening.

Serafina noticed that as Braeden and the girl entered the trees, the girl looked warily around her. The wilds of North Carolina must seem a dark and foreboding place to a civilised girl like her. She urged her horse forward to move closer to Braeden.

Braeden looked at the girl as she came up alongside him. Serafina could no longer tell if Braeden was simply being polite or if he actually wanted to be this girl’s friend, but as they rode out into the trees she felt a strange queasiness in her stomach that she’d never felt before.

Serafina could have easily followed them without their knowing it, but she didn’t. She had a job to do.

Last night she’d seen the man in the forest send the carriage to Biltmore. She reckoned that the sensible place to look for signs that the intruder had arrived was the stables.

She crept in through the back door, wary of Mr Rinaldi, the fiery-tempered Italian stable boss who didn’t take kindly to sneakers-about who might spook his horses. It was easy for her to move quietly on the perfectly clean redbrick floor, and even in the daytime there were plenty of shadows in the stables to take advantage of. The horse stalls consisted of lacquered oak boards trimmed in black railing with curving black grilles along the top. She began checking each of the stalls. Along with the Vanderbilts’ several dozen horses, she found a dozen others that belonged to the guests.

Ga-bang!

Serafina hit the floor. Her heart pounded. It sounded like a sledgehammer had hit the side of a stall. Having no idea what she was going to see, she peered down the stable’s central aisle. Disturbed dust floated from the ceiling down towards the floor, as if the earth itself had shaken, but otherwise the aisle was empty. She could see that four of the stalls at the end had been boarded up all the way to the ceiling. They were completely closed in, as if to make sure that whatever they held had no possibility of escape.

She gathered herself up onto her feet and moved slowly down the aisle towards the boarded stalls. She could feel the sweat on her palms.

The oak boards blocked her view of what was inside the stalls, so she crept up close, put her face to the wood and peered through the cracks.

A massive beast hurled itself at the boards of the stall. The flexing wood struck Serafina in the head. The surprise of it sent her tripping backwards in fear. The creature inside kicked the stall boards and slammed them with its shoulders, snorting and thrashing. The boards bent and creaked under the pressure of the pounding animal.

When she heard the stable boss and a gang of stablemen running towards the disturbance she’d caused, she scrambled into an empty stall, ducked down and hid in a shadow.

She gasped for breath, trying to figure out what she’d just seen – a massive dark shape, black eyes, flaring nostrils and pounding hooves.

A storm of questions flooded her mind as Mr Rinaldi and his men came charging down the aisle. The beast continued its terrible pounding and thrashing. The stable boss shouted instructions to his men to reinforce the boards. Serafina quickly climbed out of the back of the stall and darted from the stables before they caught sight of her.

Those were the stallions! There was no question now. Whoever it was, the second occupant of the carriage was here.

She scurried along the stone foundation at the rear of the house, pushed her body through the airshaft, crawled through the passage, pushed aside the wire mesh and entered the basement. Her presence at the estate had become known to the Vanderbilts a few weeks before, so she could theoretically use the doors like normal people, but she seldom did.

She went down the basement corridor, through a door and then down another passageway. As she stepped into the workshop, her pa turned towards her.

‘Good mornin’,’ he began to say in a pleased, casual fashion, but when he got a look at her bedraggled state, he lurched back in surprise. ‘Eh, law! What happened to you, child?’ His hands guided her gently to a stool for her to sit on. ‘Aw, Sera,’ he said as he looked at her wounds. ‘I said you could go out into the forest at night to spend time with your mother, but you’re breakin’ my heart, comin’ home lookin’ like this. What’ve you been doin’ out there in them woods?’

Her pa had found her in the forest the night she was born, so she reckoned he must have had an inkling of what she was, but he didn’t like dark talk of demons and shifters and things that go bump in the night. It was as if he thought that as long as they didn’t talk about those things they would not be real or come into their lives. She had told herself many times that she wouldn’t bother her pa with the details of what happened at night when she went out, and normally she kept that promise, but the moment her pa asked it all just started gushing out of her before she could stop it.

‘I had a terrible run-in with a pack of dogs, Pa!’ she said, choking up.

‘It’s all right, Sera – you’re safe here,’ her pa said as he took her into his thick arms and huge chest and held her. ‘But what dogs are you talking about? It wasn’t the young master’s dog, was it?’

‘No, Pa. Gidean would never hurt me. There was a strange man in the forest with a pack of wolfhounds. He sicced ’em on me somethin’ fierce!’

‘But where did he come from?’ her pa asked. ‘Was he a bear hunter?’

She shook her head. ‘I don’t know. After he got out of the carriage, he sent the carriage on towards Biltmore. I think I saw the horses in the stables. And I saw a strange man with Mr Vanderbilt this morning. Did anyone unusual arrive at the house last night?’

‘The servants have been jabbering on about all the folk comin’ in for Christmastime, but I doubt the man you saw was one of the Vanderbilts’ guests. I’ll wager it was one of those poachers from Mills Gap that we ran off the estate two years ago.’

Serafina could hear the anger seething in her pa’s voice. He was riled up that someone had done his little girl harm. He kept talking as he examined the crusted blood on her head. ‘I’ll go speak with Superintendent McNamee first thing. We’ll take a party out there to confront this fella, whoever he is. But, first off, let’s get you patched up. Then you rest a spell. Your lesson can wait.’

‘My lesson?’ she asked, confused.

‘For them table manners of yourn.’

‘Not again, Pa, please. I’ve got to figure out who’s come to Biltmore.’

‘I told ya. We’re fixing to hammer that nail till it’s sunk in deep.’

‘Sunk in my head, you mean.’

‘Yeah, in your head. Where else do ya learn things? Now that you and the young master are gettin’ on, you need to behave proper.’

‘I know how to behave just fine, Pa.’

‘You’re ’bout as civilised as a weasel, girl. I shoulda been schoolin’ ya more about the folk upstairs and how they go ’bout things, ’cause it hain’t like us.’

‘Braeden is my friend, Pa. He likes me just fine the way I am, if that’s what you’re pokin’ at,’ she said. Although, as she heard herself defending Braeden’s opinion of her, it felt suspiciously like she was lying not just to her pa but to herself. Truth was, she didn’t know if she was or wasn’t Braeden’s friend any more, and she was becoming increasingly less certain of it every day.

‘It’s not directly the young master I’m concerned about,’ her pa continued as he got a clean, wet cloth and started looking after her wounds. ‘It’s the master and the mistress, and especially their guests come city way. You can’t sit at their table if you don’t know the difference between the napkin and the tablecloth.’

‘Why would I need to know the difference between –’

‘The butler told me that Mr Vanderbilt was going to be looking for you upstairs later today. And everyone in the kitchen is fixin’ for a big supper tonight.’

‘A supper? What kind of supper? Is the stranger going to be there? Is that what this is all about? And what about Braeden – is he going to be there?’

‘That’s a bushel more questions than I got answers for,’ her pa said. ‘I don’t know anything about it, truth be told. But, other than the young master, I can’t figure any other reason why the Vanderbilts would be a-looking for you. I just know there’s a big shindig tonight, and the master sent word, and it didn’t sound so much like an invitation as an instruction, if ya get my meaning.’

‘Did they say it was a supper or a shindig, Pa?’ Serafina said, getting confused, and realising as she said it that the Vanderbilts didn’t have events by either of those names.

‘It’s all the same up there, hain’t it?’ her pa said.

Serafina knew that she had to go to the event her pa was telling her about. For one thing, it’d be the best way to see all the new people who had arrived at the house. But the obstacles immediately sprang into her mind. ‘How can I go up there, Pa?’ she said in alarm, looking at the bite marks and scratches all over her arms and legs. They didn’t hurt too badly, but they looked something awful.

‘We’ll clean the mud off ya, get the sticks and blood outten your hair, and you’ll be fine. Your dress will cover them there scratches.’

‘My dress has more holes in it than me,’ she protested as she examined the bloodstained, tattered pieces of the dress Mrs V. had given her. She couldn’t show up in that.

‘Them toothy mongrels sure did a number on you,’ he said as he examined the tear in her lower ear. ‘Don’t that hurt?’

‘Naw, not no more,’ she said, her mind on other things. ‘Where’s that old work shirt of yours that I used to wear?’

‘I threw that thing out as soon as I saw that Mrs Vanderbilt gave you something nice to wear.’

‘Aw, Pa, now I ain’t got nothin’ at all!’

‘Don’t fuss. I’ll make ya somethin’ outta what we got up in here.’

Serafina shook her head in dismay. ‘What we got around here is mostly sackcloth and sandpaper!’

‘Look,’ her pa said, taking her by the shoulders and looking into her eyes. ‘You’re alive, ain’t ya? So toughen up. Bless the Lord and get on with things. In your entire life, has the master of the house ever demanded your presence upstairs? No, he has not. So, yes, ma’am, if the master wants you there, you’re gonna be there. With bells on.’

‘Bells?’ she asked in horror. ‘Why do I have to wear bells?’

How could she sneak and hide if she was wearing noisy bells round her neck? Or did they go on her feet?

‘It’s just an expression, girl,’ her pa said, shaking his head. Then, after a moment, he muttered to himself, ‘At least I think it is.’

Serafina sat, mad and miserable, on the cot while her pa did his level best to clean and bandage her wounds. As usual, she and her pa were surrounded by the workshop’s supply shelves, tool racks and workbenches. But her pa seemed to have forgotten the work he was supposed to be doing that morning. His mind had become consumed with her.

Some of the copper piping and brass fittings from the kitchen’s cold box sat in a twisted clump on the bench. The previous day, her pa had explained something about an ammonia-gas brine system, intake pipes and cooling coils, but none of it took. He’d raised her in his workshop, but she had no talent with machines. She couldn’t remember anything about the contraption other than it was complicated, kept food cold and was one of the few refrigeration systems in the country. The mountain folk kept their food cold by sticking it in a cold spring tumbling down into a creek, which seemed far more sensible to her.

As soon as her pa was done fussing with her, she slipped off the bed, hoping he’d forget his threat to make her rest. ‘I’ve gotta go, Pa,’ she said. ‘I’m gonna sneak upstairs and see if I can spot the intruder.’

‘Now, listen here,’ he said, holding her arm. ‘I don’t want you confrontin’ anybody up there.’

She nodded. ‘I’m with ya, Pa. No confrontin’. I just want to see who’s up there and make sure everyone is all right. No one will ever see me.’

‘I’m needin’ your word on this,’ he said.

‘You got my word, Pa.’

Off she went to the main floor. She spotted a few guests strolling this way and that or lounging in the parlours, but nobody suspicious. She moved up to the second floor next, but she didn’t see anything out of the ordinary there, either. She scoured the house from top to bottom, but there was no sign of the stranger she’d seen with Mr Vanderbilt or anyone else who seemed like they might have been the second passenger in the carriage. She listened for scuttlebutt from the servants as they prepared for the event in the Banquet Hall that evening, but she didn’t pick up anything other than how many cucumbers the cook wanted the scullery maid to fetch and how many silver platters the butler needed for his footmen.

She tried to think through everything she had seen the night before, wondering if she’d missed any clues. What had she actually seen when the bearded man threw his walking stick up into the air towards the owl? And who was the second passenger who’d remained in the shadows of the carriage? Was it the stranger she’d seen walking with Mr Vanderbilt? And who was the feral boy who had helped her? Was he still alive? How could she find him again?

Another bushel of questions I don’t have answers to, she thought in frustration, remembering her pa’s words.

Later that afternoon, when she walked back into the workshop, her pa asked, ‘What did you find out?’

‘A whole lot of nothin’,’ she grumbled. ‘No sign of anyone suspicious at all.’

‘I spoke to Superintendent McNamee. He’s sendin’ out a group of his best horsemen to hunt down the poachers.’ As he spoke, her pa wiped his grease-smeared hands with a rag.

‘Elevator actin’ up again, Pa?’ she asked.

Her pa had often boasted that Biltmore had the first and finest electric elevator in the South, but he seemed a mite less keen on the machine today.

‘The gears in the basement keep gettin’ all gaumed up when it hits the fourth floor,’ he said. ‘Everwho installed the thing got them shafts all sigogglin’, this way and that. I swear it ain’t gonna work proper till I tear out the whole thing and start again.’ He waved her over to him. ‘But take a look at this. This is interestin’.’ He showed her a thin piece of sheet metal that looked like it hadn’t just broken but had been torn. It was odd to see metal ripped like that. She didn’t even know how that was possible.

‘What is that, Pa?’ she asked.

‘This here little bracket was supposed to be a-holdin’ the main gear in place, but whenever the elevator ran it kept flexing back and forth, you see?’ As he spoke, he showed her the flexing motion by bending the sheet metal with his fingers. ‘The metal is plenty strong at first. Seems unbreakable, don’t it? But when ya bend it back and forth over and over again like this, watch what happens. It gets weaker and weaker, these little cracks start, and then it finally breaks.’ Just as he said the words, the metal snapped in his fingers. ‘You see that?’

Serafina looked up at her pa and smiled. Some days, he had a special kind of magic about him.

Then she looked over at the other workbench. Somewhere between mending the elevator, fixing the cold box and tending to his other duties, her pa had cobbled together a dress for her made out of a burlap tow sack and discarded scraps of leather.

‘Pa . . .’ she said, horrified by the sight of it.

‘Try it on,’ he said. He seemed rather proud of the stitching he’d done with fibrous twine and the leather-working needle he sometimes used to patch holes in the leather apron he wore. Her pa liked the idea that he could make or mend just about anything.

Serafina walked glumly behind the supply racks, took off her tattered green dress, and put on the thing her pa had made.

‘Looks as fine as a Sunday mornin’,’ her pa said cheerfully as she stepped out from behind the racks, but she could tell he was lying through his teeth. Even he knew it was the most god-awful, ugly thing that ever done walked the earth. But it worked. And to her pa that’s what counted. It was functional. It clothed her body. The dress had longish sleeves that covered most of the punctures and scratches on her arms, and a close-fitting collar that hid at least part of the gruesome cut on her throat. So at least the fancy ladies at the shindig or the supper, or whatever it was, wouldn’t swoon at the corpsy sight of her.

‘Now, sit down here,’ her pa said. ‘I’ll show you how to behave proper at the table.’

She sat reluctantly on the stool he placed in front of an old work board that was meant to represent the forty-foot-long formal dining table in Mr and Mrs Vanderbilt’s grand Banquet Hall.

‘Sit up straight, girl, not all curvy-spined like that,’ her pa said.

Serafina straightened her back.

‘Get your head up, not hunched all over your food like you gotta fight for it.’

Serafina leaned back in the way he instructed.

‘Get them elbows offen the table,’ he said.

‘I ain’t no banjo, Pa, so quit pickin’ on me.’

‘I ain’t pickin’ on you. I’m tryin’ to teach ya somethin’, but you’re too stubborn-born to learn it.’

‘Ain’t as stubborn as you,’ she grumbled.

‘Don’t get briggity with the sass, girl. Now, listen. When you eat your supper, you need to use your forks. You see here? These screwdrivers are your forks. The mortar trowel there is your spoon. And my whittlin’ blade is your dinner knife. From what I’ve heard, you gotta use the right fork for the job.’

‘What job?’ she asked in confusion.

‘For what you’re eatin’. Understand?’

‘No, I don’t understand,’ she admitted.

‘Now, look straight ahead,’ he said, ‘not all shifty-eyed like you’re gonna pounce on somethin’ and kill it at any second. The salad fork here is on the outside. The dinner fork is on the inside. Sera, you hearin’ me?’

She didn’t normally enjoy her pa’s etiquette lessons, but it felt kind of good to be home, safe and sound, suffering through yet another one.

‘You got it?’ he asked when he’d finished explaining about the various utensils.

‘Got it. Dinner fork on the inside. Salad fork on the outside. I just have one question.’

‘Yes?’

‘What’s a salad?’

‘Botheration, Serafina!’

‘I’m askin’ a question!’

‘It’s a bowl of, ya know . . . greenery. Lettuce, cabbage, carrots, that sort of thing.’

‘So it’s rabbit food.’

‘No, ma’am, it is not,’ her pa said firmly.

‘It’s poke sallet.’

‘No, it ain’t.’

‘It’s food that prey eats.’

‘I don’t want to hear no talk like that, and you know it.’

As her pa schooled her in the fineries of supper etiquette, she got the notion that he’d never actually sat at the table with the Vanderbilts. She could see that he was going more on what he imagined than live experience, and she was particularly suspicious of his understanding of salads.