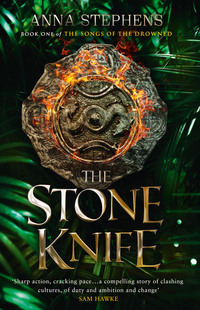

The Stone Knife

‘That said, a lot of our people take the test, myself included. I spent my childhood convinced Malel had put me in the world to walk the snake path. When I was old enough, a shaman gave me and the other candidates the spirit-magic. I was so excited at the prospect of the spirits deadening me to the Drowned’s call. And it worked – at first.’

Lilla fell silent and Tayan realised Xessa was watching the warrior. ‘Can you see his lips?’ he signed and she nodded.

‘What happened then?’ she asked, even though she knew the story. It was important the Xentib understood why the snake path was not stepped upon lightly. Tayan shifted on the bed so he could see the rest of the room’s occupants. Lilla gave him a wan smile. Ilandeh and Dakto were silent, rapt.

Lilla signed as he spoke. ‘I heard the spirits. A sort of high, ululating whine. It was all I could hear, just that, and I was so happy, because it was working. I was going to be eja.’ He paused and bitterness chased regret across a face too gentle to be a warrior’s. ‘But then it changed. I could see the spirits too, not just hear them, and they weren’t friendly. They were angry.’

‘What did they look like?’ Ilandeh asked and Tayan translated for Xessa.

Lilla shuddered and met the shaman’s eyes. ‘Awful,’ he whispered and Tayan nodded. While his journeys were mostly spent with ancestors and familiar guides, he’d encountered enough wild spirits in his time to have a healthy respect for both their abilities and the terror and awe they inspired.

‘What happened then?’ Dakto demanded, an ugly sort of fascination in his face.

‘The spirit-magic lasts most of a day, and I spent those hours screaming and fighting things that existed only in the spirit world instead of being able to think and fight and draw water or kill Drowned in this world. And that was the end of my dream.’

‘It takes some like that, love, and there is no shame in it,’ Tayan said and signed at the same time. ‘And now look at you, one of the finest Tokob warriors, your feet firm upon the jaguar path instead. Now the monsters you fight come from Pechacan and its dominions, and that is a fight of just as much importance.’

Lilla mustered a smile for them all, but Tayan knew him and knew it was an old pain and an old shame that he wouldn’t let go.

Xessa snapped her fingers, drawing their attention. ‘Besides, how would I have won any glory if you’d been eja?’ she signed and the Tokob laughed, the Xentib looking on in polite incomprehension.

‘So no,’ Lilla finished, ‘our warriors can’t also become ejab, even if just for the duration of a Wet. It’s too much to ask, even if not for the different fighting styles each employs. Stabbing a Pecha and defeating a Drowned … they’re completely different. We can’t – we won’t – ask our people to face a threat they’re not trained for, or to risk the spirit-magic failing or killing them or making them … different for the rest of their lives. And so we manage, as we have always done.’

‘And if we’re to continue managing, this eja needs her sleep,’ Tayan said, turning back and signing to Xessa. He bent to kiss her cheek.

‘But the Zellih?’ she signed.

‘I’ll come back tonight,’ he promised. ‘I’ll tell you everything then. Sleep now.’

Xessa scowled, but her eyelids were already drooping and Ossa was deeply asleep, paws twitching. Tayan stood and ushered the others out and they were silent until they were back under the open sky.

‘Forgive us,’ Ilandeh said with a grimace. ‘The Sky City … well, it’s beginning to feel like the first proper home we’ve had since Xentiban fell. We have friends here and … we’re afraid. Of the Drowned, of the Empire, of what’s going to happen. If we offended you, any of you, we are sorry.’

The Tokob exchanged looks, but what was there to say? They were all afraid.

‘What about your retired ejab?’ Dakto asked after a decent pause. ‘They couldn’t resume the duty?’

‘No,’ Tayan said and there was an edge in his voice. He was tired, he was worried, and the Xentib endless curiosity scraped at him. He was self-aware enough to know he had the same effect on others, but today he didn’t feel like being charitable.

‘For most, the magic eventually opens a permanent channel between the eja and the spirit world. They give up the duty only when the spirits force them to, when they can’t stand the magic any more and their hearts and thoughts are permanently changed. We honour them and care for them, for they are living testimonies to sacrifice – their lives for ours – but to welcome the spirits now would likely kill them before they even reached the Swift Water. After a lifetime of sacrifice, who would ask them to give even more?’

Tayan’s heart was hurting as they reached the breeze and sunlight and bustle of the upper market again. ‘It was nice to see you both,’ Lilla said, as ever reading his husband’s mood perfectly, ‘but I’m afraid we are both still tired from our travels.’

When the Xentib had said their farewells and vanished into the market, Lilla wrapped big arms around Tayan’s shoulders and pressed a kiss to his hair. ‘Let’s go back to bed,’ he murmured. ‘I just want to forget about the world for a while.’

‘Mm. Don’t forget my snake on a skewer, though,’ Tayan said into his neck.

‘What? You didn’t even ask her about Toxte,’ Lilla grumbled. ‘That bet is—’

‘You really think if they’d started fucking in the last few weeks that he’d be anywhere but at her sickbed? You’ve just propositioned your innocent, unworldly husband in the middle of the day, after all. Which is scandalous, by the way. I am shocked. Really very shocked.’

‘Yes, I can tell,’ Lilla muttered as Tayan’s hands stroked down his hips. Tayan smiled and stretched up for a kiss, and then took his hand and led him home through the market and past the food vendors until Lilla laughingly gave in and bought them both snake on a skewer.

They ate it in bed.

ENET

The source, Singing City, Pechacan, Empire of Songs

122 nd day of the Great Star at morning

The song was a brassy, contented rumble today, stroking along the nerves of every citizen who heard it, its ceaseless melody rippling through hearts and minds and bones and uniting them all in glory. Purpose. Triumph.

The song was their magic, their strength, never ending; it whispered its harmonies into the spirits of every person within the Empire’s bounds, from full-blood Pecha to the lowest slave. It was a sound that Enet had heard every day since her first breath, that made her not only who she was but part of a greater whole. For the song was eternal and soon would be heard across all Ixachipan to the Singer’s glory and the Empire’s triumph. And then, finally, they would have peace in which to attempt the great work – the waking of the world spirit.

Enet lay among pillows with the Singer, her smooth skin lightly sheened with sweat. Beside her, the faintly iridescent glow in the Singer’s own skin was fading as satiation took over from urgency. Enet smiled to herself, a small and secret smile, and trailed her fingers over his lower belly; he twitched and growled, and she laughed. Laughed, but stopped the caress. Best not to rouse his ire so soon after his lust.

‘Eleven years, holy lord, since the magic passed into you and raised you to greatness,’ she murmured. ‘How much you have accomplished in that time. And how your strength yet waxes. Surely you will be remembered as one of our mightiest Singers.’ The Singer didn’t respond. ‘The greatest,’ Enet whispered and caught the hitch in his breath. Ah.

‘Because of you, Tokoban and Yalotlan will be brought under the song. Because of you, Ixachipan will know peace.’ She leant forward to kiss his ear and breathed the next words. ‘Because of you, the world spirit will awaken.’

‘And I will be its eternal consort,’ the Singer murmured. He stared at the bright murals painted on the ceiling, seeming to speak only to himself. ‘The god at its side, the vessel for its will. Forever.’

‘Yes,’ Enet said. ‘Forever.’ Awe and fidelity filled her to the brim. She had a child with this man; her place, too, was guaranteed. She would make sure of it.

‘You are thinking,’ the Singer began, scowling at her. ‘I can’t quite … tell me your thoughts.’

She leant up on her elbow and gave him a lazy smile. ‘Holy lord, it is not easy to think of anything when you have brought me such pleasure.’ His scowl remained, but it was tempered with a smirk. Still, he waited for an answer. ‘I was thinking of the stories my body slave told me when I was a girl. She said the earliest Singers didn’t ascend to godhood, holy lord. She said that, before we truly understood the magic of the songstone and the world spirit’s will, they remained mortal and died as mortals. It saddened me, to think of their great sacrifices going unrewarded.’

‘Heresy,’ the Singer grunted. ‘We have always ascended. We always will. We become the highest expression of our nature. Instead of controlling the song, we go deeper, further, into it. We become song. To say otherwise is to court disaster.’

The Singer rolled towards her and examined her from beneath heavy lids. His eyes, though, were sharp. Sharper than most gave him credit for. He was tall and broad, heavy in the shoulders and arms and sculpted by the song-magic that suffused his ordinary features and strong jaw with divinity, until he was as far above mortals as the pyramid’s songstone cap was above the earth.

The magic didn’t glow in him now that his desires, as ever heightened by the song itself, were sated. Still, Enet allowed herself to be overcome by the power of him lying beside her, by her proximity to glory. ‘To wonder such things as a child is barely acceptable,’ he said, bringing her thoughts back to the conversation. ‘To raise them now is blasphemy, and to do so here, in the very source of the song itself, in my presence … Should I have you punished, Enet, Spear of the City?’

Enet smiled wickedly. ‘As the great Singer desires,’ she murmured. ‘And such desires he has. Of course, I but make idle conversation. Our son asked me for some old tales this morning and those sprang to mind. I think I first heard them when I was about his age. But of course, holy lord, I shall accept your punishment with due humility.’ There was another layer to the story she’d been told as a child, but she didn’t so much as acknowledge it in the depths of her mind, let alone speak it aloud.

Singer Xac grunted again. ‘You’ve never been humble in your life,’ he said, but there was the tiniest smile at the corner of his mouth. Enet let out a silent breath that her gamble had paid off. The Singer’s moods changed faster than a hawk’s stoop and there’d been a chance, just a breath of a chance, that he would have ordered her punished for her arrogance. Despite the truth of it. ‘I hope you at least killed the slave.’

‘Not quite,’ Enet said and pointed to the old woman who knelt at the far wall in the shadow of Nara, leader of the Singer’s personal bodyguards – the Chorus. ‘We removed her tongue though, so that she could not repeat such foulness.’ She made a noose from the Singer’s long hair and looped it around her own throat; then she leant in for a lingering kiss that would stir his song-given desires again.

‘They are strange stories though, are they not?’ she breathed against his mouth as his hand grabbed her shoulder with bruising force.

‘Enough,’ the Singer snarled. ‘Enough talk. It is impossible. Singers are gods and ascend as gods. Those they take with them become divine, too.’

‘Impossible,’ Enet agreed, the word blurred against her mouth as the Singer kissed her again, intent once more upon her body.

‘Perhaps I will put a child in you this time,’ he muttered against her throat.

Enet’s insides clenched. ‘We already have Pikte, holy lord. A finer son you could not hope for. And your first song-born.’ He had other children, at least four that she knew of from before he became Singer, and more since, but Pikte occupied that special, sacred space of the first born from his divinity.

The Singer paused, leaning over her. His expression was hard now. Disappointed. ‘One child. One.’

Enet affected a careless laugh and put her hands on his hips, coaxing him forwards. He resisted. ‘I am Spear of the City, holy lord. I administrate your councils, run the Choosers and the flesh markets and oversee the provision of songstone and erection of new pyramids. My days are full of work on the Empire’s behalf and for your glory. You have fifty other courtesans, great Singer,’ she added when he seemed unmoved. ‘Any of the women among them can and do give you children, and I know of at least five of the men who are actively seeking promising youngsters you might wish to adopt with them. Our time here together is for pleasure, not for—’

‘You are a courtesan,’ the Singer interrupted. ‘My courtesan.’

‘Spear of the City,’ Enet corrected him with a smile. ‘And so much more than a mere vessel for your seed.’

The Singer went very still and too late the words echoed in Enet’s head, the tone of them misjudged and faintly repulsed, curdling with the choir singing softly in another room. Their teasing, faintly barbed banter was a spice to their relationship, but she knew that this time she’d gone too far.

Singer Xac reared up, lurching off her as if she were a week-dead corpse. ‘What?’ His tone was deadly.

Enet scrambled onto her knees and put her forehead to the mats. The quick patter of feet behind her and then the cold, lethal point of Nara’s spear was pressed against the side of her neck. Heartbeats later the soft weight of her body slave crashed onto her back, shielding her from harm.

‘Holy lord?’ Nara’s voice was colder than the obsidian. Just as deadly. The Singer was quiet for far too long and Enet began to sweat again. The slave was little more than wrinkled skin stretched over bird-hollow bones, but her elbow was jammed in the crook of Enet’s neck and shoulder as she sought to protect her, though the absurdity of their tangle was more painful than the pressure. It was also deeply humiliating.

And then the Singer began to laugh. ‘I do love Chitenecah slaves,’ he said. ‘Loyalty is bred so deep in their bones they can’t help themselves. Either that or she wants to fuck you, eh, Enet?’

Enet blushed but was silent. The Singer waved and Nara stepped away and hauled the slave off her back. She still didn’t move. Around them, the song grumbled and then settled, and the Singer’s emotions were palpable, swirling through the source like the breeze through the colonnaded wall out to the gardens.

The slave scurried away and Nara retreated to the wall, slow and wary. Enet still didn’t move.

‘Dancers,’ the Singer called and she heard the slap of bare feet running into the room. A drum began, and then a reed flute. The Singer settled back in the pillows. Enet still didn’t move.

The Spear of the City let none of the scalding humiliation she felt show on her face or in her manners. She refused to think of it, of how the Singer had left her kneeling there through seven dances, before finally dismissing her like a whore, not a courtesan. Like a no-blood slave.

Her own slave had a red handprint slapped into the side of her face and a bead of blood at the corner of her mouth. It was deserved; Enet’s humiliation was not. With ruthless precision, she excised that thought from her mind.

She’d ordered the litter’s curtains left open so that she could be seen as her slaves bore her and Pikte back towards her estate. The old woman laboured behind them where Enet didn’t have to look at her. She let the Pechaqueh awe and excitement at seeing their Spear soothe her until the memory of what the Singer had done … She did not complete the thought, bending her mind to adoration of the holy lord. If Singer Xac or one of his Listeners was reading her through the song, they would find nothing in her heart and mind but love.

The slaves trotted across the plaza in front of the great pyramid which held the source, the Singer’s temple-home and the heart of his power. They moved onto the Way of Prayer, travelling past temples to the holy Setatmeh and former Singers, and out into the city. The wide roads here were built of limestone and swept daily to keep them bright. They contrasted with darker stone of the temples and the councillors’ great palaces. Enet had a palace here herself, owing to her position as Spear, but she preferred her family estate on the outskirts of the city. The air was sweeter, and there were fewer beggars.

Her bearers were swift and smooth, and soon enough they passed from the temple district into the markets. This close to the great pyramid and palaces, only the finest pottery and textiles and carvings were sold, only the freshest and sweetest fruits and meats. Choosers patrolled in pairs, armed with stone-headed clubs, their presence scaring off the cast-out and abandoned who tried to steal from the shops and stalls. There were few enough about this afternoon; the monthly offering to the holy Setatmeh was only a few days away, and those with no status or protection knew better than to fall beneath the gazes of the Choosers so close to new moon.

It both pleased and irritated Enet. Pleased, because she did not have to smell their stench or see their filth. Irritated, because the Choosers would have to hunt them down, searching the whole city and the surrounding fields for offerings.

The Spear put it from her mind and instead allowed Pikte to climb into her lap so that he could point out the market’s finer items. The boy had seen one Star cycle since his birth – eight sun-years – and was as lively and clever as she had prayed for. She revelled in the simple joy of his presence, of his warm wriggling in her lap. She had no need of more children – another thought she cut off before it could form.

Pikte’s status as offspring of the Singer made him both someone for the ambitious to befriend, particularly as he grew older, and a target for disaffected councillors or those ruined by the latest purge. In addition to the four litter-bearers, four warriors surrounded them, clearing the way and ensuring no one came too close.

Everywhere in this district, Pechaqueh in brightly dyed and woven kilts and tunics hurried, glancing up at the darkening sky and the coming rain. Among them were slaves in undyed maguey cloth, holding purchases or carrying messages, their eyes down and brands visible on their upper arms.

‘Look!’ Pikte exclaimed, pointing. ‘Axib.’

Enet gave him an indulgent smile. ‘And how do you know that?’

‘Because they shave one side of their heads. See? And they’re free, too.’

‘So they are,’ Enet murmured, distracted. Free Axib in the most exclusive market in the Singing City. It was … unusual. ‘Guard,’ she called and the warrior leading them looked back. ‘Tell the next Chooser you see to find out what those free are doing in here and move them on. They’re unsightly.’

‘As the Spear commands,’ the man said.

‘They weren’t born free, though,’ Pikte added as they passed the trio. He pointed again. ‘Look, their slave brands have been cut through.’ He was quiet for a while, craning his neck to keep them in view as the litter passed. ‘How horrible to be a slave.’

‘And yet now they are happy and productive members of the Empire,’ Enet said, making him look at her. ‘Why?’

‘Because they have embraced the song and become Pechaqueh in their hearts,’ the boy said obediently. Enet smiled at him and he grinned back, delighted at her approval. ‘Have you ever been outside the Empire? Have you ever not heard the song?’

She shifted him in her lap again. ‘I have, yes.’ His eyes were round. ‘Many years ago. The silence is … unpleasant.’ The Spear changed what she’d been about to say at the last moment. She had no desire to terrify her son. ‘You may hear it too, one day, when you are older. If you join the Melody and become a great warrior, it may be your destiny to travel outside of the Empire and hear the quiet.’

The awful, clanging, emptiness in the blood and body. The disconnection from people and duty and honour. The violent absence of purpose.

Pikte was watching her and she pushed away the memories and found another smile for him. ‘There now, it is not so terrible. All our warriors have done it at least once, even the lowliest dog warriors. But before you are old enough, all Ixachipan will have been brought under the song. We are already close, are we not?’

‘Yes, Mother. And my father the holy lord will wake the world spirit and put an end to hunger and disease and death.’

The Spear smiled. ‘Almost,’ she said indulgently, but the boy was no longer listening. He gave an excited squeal.

‘Oh, look, look at it!’ He scrambled out of her lap and slid off the litter; the slaves stopped immediately and the nearest slave warrior wrapped a long arm around him to hold him close and safe. Pikte didn’t struggle; he peered around the guard’s waist into the shade beneath a bright awning. In a cage of thin bamboo slats sat a spider monkey, young and small and depressed, one tiny paw curled around a bar. ‘I’m going to look closer,’ he said, with the unconscious authority of someone who had never been refused a request by a slave and never would be. The guard looked to Enet and she flicked her fingers at them. Pikte wriggled with impatience, and the warrior released him, following closely as the boy scampered into the shade.

The merchant approached, a Pecha of course, and well enough dressed. ‘Under the song, high one.’

‘Under the song,’ Enet said. ‘My son likes the monkey.’

‘Ah, a fine specimen, brought from the forests in Quitoban only a moon ago. Young enough to tame. Healthy too – a young male. They make good pets, high one.’

‘It comes with the cage?’

‘Of course, and a fine deerskin collar and tether. Already I have trained him to sit on my shoulder. May I demonstrate for the honoured child?’

‘If it bites my son, I will take everything you own and cast you onto the streets for the Choosers and flesh-merchants to fight over.’

The vendor blanched but managed a low, bobbing bow. He sweated as he eased open the cage. The monkey came to him readily enough and he threaded a thin cord through its collar and then coaxed it onto his shoulder. From there it leapt to Pikte’s head and Enet’s guards tensed, fingering weapons, but the boy laughed in delight, standing immobile and rolling his eyes up as if to see through the top of his own skull. He glanced at Enet; she said nothing. Waiting. Testing.

‘He is a fine little beast,’ Pikte said eventually, nearly masking his regret, ‘but we must go. Thank you for letting me look at him.’

Enet’s heart swelled with pleasure. He’d been polite and courteous and restrained, honouring the Pechaqueh status without forgetting his own. ‘We’ll take him,’ she said and the merchant jumped. Pikte gasped and whirled to face her and the monkey screeched, paws clinging to his hair and its long tail tightening around his throat. ‘My slave back there will pay you. I am sure the price will be fair. You, carry the cage. And you, boy, will keep it under control on the journey home, do you hear me?’

‘Truly?’ Pikte breathed, and his joy wiped away the dregs of sourness arising from Enet’s humiliation. She nodded and the vendor passed the tether to him and this time his thanks were effusive and accompanied by a blinding smile he shared equally between the Pecha and his mother. Enet gave Pikte the long, slow cat-blink of affection that was their secret expression of love and he would have run to her if the monkey hadn’t been tangling them both in its tether.

They hadn’t even cleared the markets before Enet began to regret her decision; the monkey stank and, despite his promises, Pikte couldn’t keep it from climbing all over the litter and himself, or from chattering and screaming and tugging at the collar on its neck. Eventually, she made him put the animal back in the small cage the slave woman carried at the rear of their little procession. Pikte knew better than to sulk, though he flirted with the idea for a few moments before subsiding into polite silence. He was learning.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.