Mr Atkinson’s Rum Contract

So I did something I’d never thought of doing – I stayed a night at the hotel. Arriving at Temple Sowerby around teatime, I parked near the maypole, beside the large stone from which John Wesley was said to have preached in 1782. It was a crisp November day. Across the road, the curtains of the hotel had not yet been drawn, and its brightly lit reception rooms radiated hospitality. Before checking in, I went for a short stroll, as far as the old tannery buildings at the other end of the village. Walking round the green, I found myself appraising Temple Sowerby as if visiting for the first time; with its handsome Georgian houses, coaching inn and red sandstone church, it seemed a delightful place. Much more peaceful than I remembered, too, since a new bypass had diverted all the lorries which had once rumbled through the village.

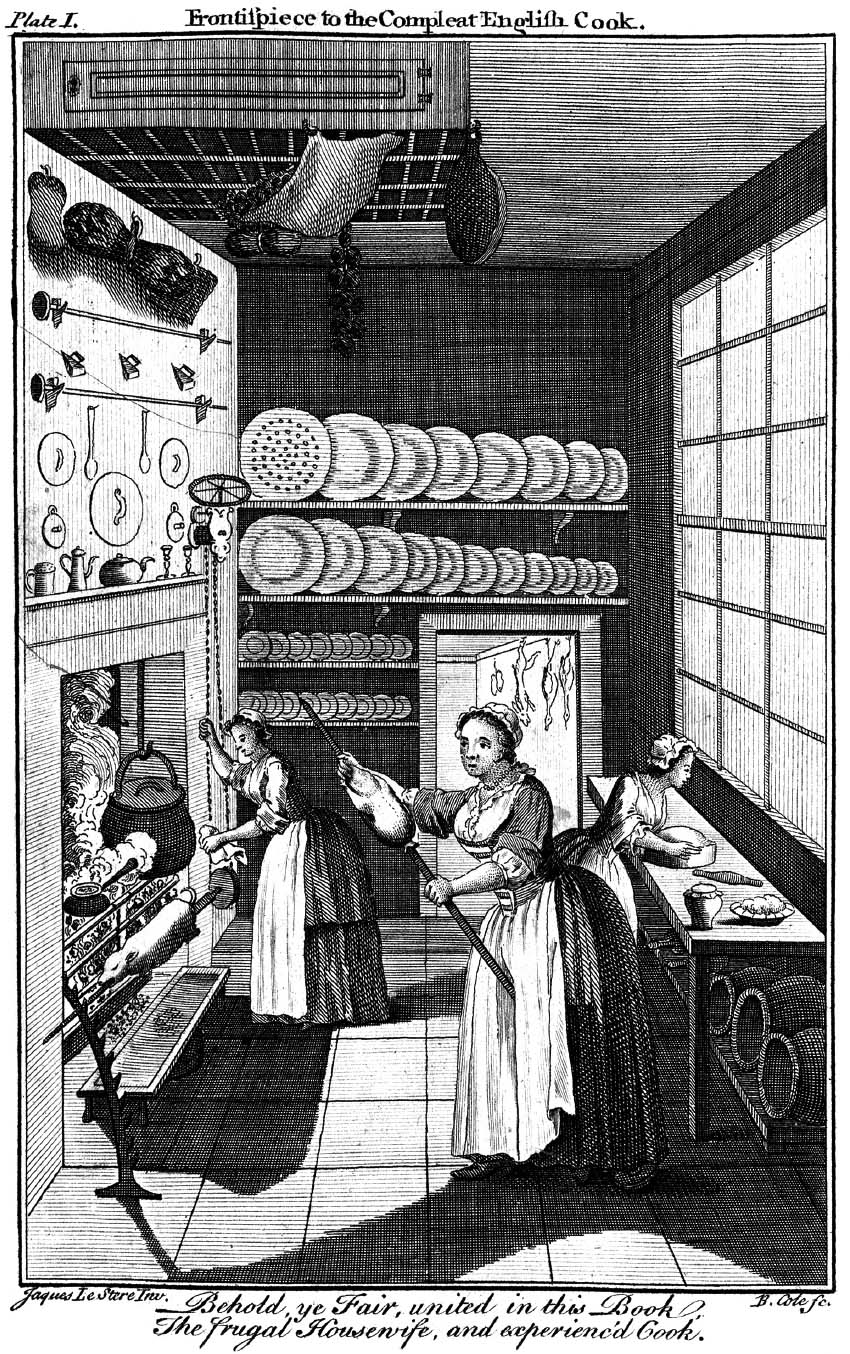

The frontispiece of Bridget’s copy of The British Housewife.

Over at the hotel, Julie Evans, one of the owners, greeted me warmly. She already knew about my connection to the house, and had reserved a room for me at the back, with a view down the garden. It was nice and cosy, in a chintzy kind of way, and the ensuite bathroom, with its Jacuzzi tub, was a definite upgrade from the spartan facilities of the Atkinson era. Even so, a small, churlish part of me resented the fitted carpets and double glazing, and yearned for the house of my grandparents. As a child, my favourite place had been the gallery, with its clattery floorboards and oak furniture, some of which now dominated my living room in south London. But it seemed that when Temple Sowerby House was turned into a hotel, in the late 1970s, the gallery had been carved up to make bedrooms, including the one I would be sleeping in. To describe my emotions as agitated would be an understatement; as I sat down to dinner, the only guest that night, I had never felt more lonely.

I had almost finished eating when Julie appeared, clutching a scrap of paper. ‘I’ve just remembered something,’ she said. ‘A few years ago, this person came to stay, and she told me her ancestors used to live here. Perhaps you should get in touch?’ She handed me the slip, on which was written an unfamiliar name – Phillipa Scott – along with a telephone number. I was intrigued.

Julie took pity on me after my solitary meal, and we chatted in the parlour. She and her husband Paul had owned the hotel for ten years, and she was clearly so fond of the place that I found myself letting go of the last of my proprietorial feelings. I’d brought a shoebox full of old family papers up from London with me, and we leafed through them together. Then I asked Julie the question I’d been burning to put to her since arriving – what could she tell me about this ‘receipt book’ that was mentioned on the hotel website? She left the room and returned a couple of minutes later, cradling an old quarter-bound book. She handed it to me; I opened it cautiously, not knowing what might be inside, and was amazed to find almost eight hundred recipes, handwritten in highly legible script.

It was evident from the sheer variety of meat, fish and game dishes in her repertoire that Bridget Atkinson had kept an excellent table. Many of her recipes included spices and flavourings that to this day carry a whiff of the exotic, such as cinnamon, ginger, nutmeg, curry powder, candied lemons and orange flower water. Although the instructions she gave were cursory at best, and her methods on the antiquated side – she was, after all, cooking over an open fire – many of the recipes, especially the puddings and preserves, seemed perfectly relatable to the present. I could imagine trying to make them at home.

Not so the recipes in the last third of the book, where Bridget offered remedies for every conceivable domestic situation or ailment: ‘For Berry Bushes infested with Caterpillers’; ‘To distroy Moths’; ‘To prevent Milk from having a taste of Turneps’; ‘A Pomatum for the Face after the Small Pox’; ‘To draw away a Humor from the Eyes’; ‘For worms in Children’; ‘Against Spitting of Blood’; ‘To prevent bad effects of a Fall from a high place’; ‘To cure the Bite of a Mad Dog’; ‘For Insanity’. Some of her preparations sounded downright lethal. On a loose piece of paper tucked into the book I found ‘Mrs. Atkinson’s Receipt’, a concoction of rhubarb, laudanum and gin, all mixed into a pint of milk; it was not clear what condition it was intended for, but it seemed as though it may have been a case of kill or cure.

Bridget would have been in her seventies when she started compiling this volume for her daughter – it was odd to think she might well have written it in the same room in which I was at that moment sitting. For so long, I had associated Temple Sowerby House with death and decay; only now could I sense it as a bustling family home. In all my life, I had never coveted a single object so much as this wondrous book – so I felt crushed when Julie explained that it belonged to a private collector from Newcastle, and would soon have to be returned. I must have looked so downcast that Julie insisted I should immediately write to the owner, Miss Dunn, to ask whether I might buy the book; indeed, she thrust pen, paper and envelope at me, and promised to post my letter.

WHEN I OPENED the curtains the next morning, the sky was a brilliant blue; overnight had seen a heavy frost. After breakfast I walked across the road to the churchyard, crunching through glittery grass in search of Atkinson graves; then I set off for Northumberland, to spend a couple of nights with my godmother near Corbridge. My route over the Pennines took me on a zigzag road up the steep side of the Eden valley, through the ancient lead-mining town of Alston and across an ocean of bronze heather, dropping down alongside the South Tyne – a spectacular drive. That afternoon I had a couple of hours to spare, so I visited Chesters Fort, one of several Roman garrisons along Hadrian’s Wall, now maintained by English Heritage. I knew from my family research that some cousins, the Claytons, had once lived in the big house near the ruins, and had been responsible for their excavation – Bridget’s daughter, Dorothy, had married Nathaniel Clayton, the Newcastle lawyer who purchased the property.

Wandering around the neat stone footings, I struggled to imagine five hundred Roman cavalry ever having occupied such a peaceful spot. As drizzle hardened into rain, I took refuge in the small museum attached to the site. Near the entrance was a glass case devoted to the life of John Clayton, owner of Chesters for much of the nineteenth century. Among the objects on display was an old book which had belonged to his grandmother, Bridget Atkinson – as usual, her name was inscribed on the title page. Then something even more extraordinary caught my eye. It was the facsimile of a letter written by Bridget in January 1758, when she would have been in her mid-twenties, in which she was begging her sister to placate their mother, who was furious that she’d got married the previous Saturday without telling anyone. My heart pounded as I processed this – did it mean Bridget had eloped? And how had the museum come by this letter?

On my return to London, I wasted no time chasing up my leads – within minutes of arriving home, I had dug out the family tree and unfurled it on the kitchen table. First of all, I needed to locate Phillipa Scott, the mysterious woman whose details Julie Evans had given me. There she was, my fourth cousin – our last mutual ancestor was Bridget’s son Matthew Atkinson, the one who died in 1830. I googled her, and soon landed on the website of a needlework expert living in Appleby, six miles from Temple Sowerby – with the same distinctive spelling of her first name, this was surely the right person. It was almost midnight on a Sunday, but the urge to make contact with this complete stranger was too powerful to resist. In a short email, I explained who I was and where I’d just been. About three minutes later, Phillipa’s reply announced itself in my inbox. Hello! And, yes, she had stayed at Temple Sowerby House some years earlier, but also remembered visiting in the 1960s, as a child. ‘Is it my imagination,’ she wrote, ‘or was there a crocodile on the top landing?’

Phillipa and I spoke on the telephone the following day, and for me it was a cathartic experience. We hit it off immediately, and discovered how much we had in common; although we belonged to different branches of the tree, we shared the same deep roots. We chatted for an hour, and afterwards I felt so overwhelmed with joy that I burst into tears. A few weeks later, Phillipa put me in touch with David Atkinson, her first cousin – my fourth cousin – who invited me to stay at his house in Cheshire so that I could search through his collection of family papers. He was trusting enough to let me carry away a suitcase full of them.

I also made contact with the curator of the museum at Chesters, Georgina Plowright, who delivered a surprising piece of news. She had recently unearthed a treasure trove of correspondence between the Atkinson and Clayton families, six large boxes spanning the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, in the Northumberland Archives, buried among the papers of another family, the Allgoods of Nunwick Hall. (Apparently one of Bridget Atkinson’s great-great-granddaughters, Isabella Clayton, had married an Allgood.)

And then there was Bridget’s ‘receipt book’, the scent of which had lured me north in the first place. Two days after my return, I received a call from Irene Dunn in response to the letter I had written from Temple Sowerby. She told me she was a retired librarian with a special interest in books about food; she had found Bridget’s manuscript at an antiquarian bookseller’s in Bath about fifteen years earlier. It so happened that I had approached Irene at the perfect moment. She was now looking to downsize, and was tickled by the thought of selling the book to me, a descendant of Bridget. One bright Saturday in January I travelled by train up to Newcastle to meet Irene for lunch in a restaurant on the Quayside, and to carry my prize home.

SO THIS IS THE STORY of how I found my eighteenth-century family. It was as though Bridget’s cookbook was the key I had been searching for, since doors immediately began to open. The thousands of old letters that fell into my lap as a result of my miraculous trip to Temple Sowerby – they were just the start. Within a few months I had located significant quantities of Atkinson correspondence in more than a dozen public archives and private collections on both sides of the Atlantic. My ancestors, it emerged, had occupied ringside seats at some of the most momentous episodes in British imperial history, most notably the loss of the American colonies, then the economic collapse of the West Indies. When they first sailed to Jamaica, in the 1780s, it was the most valuable possession in the empire; when they left, in the 1850s, it was a neglected backwater. Moreover, through the copious correspondence they left behind, I learnt the intimate details of their lives. Richard ‘Rum’ Atkinson, in particular, emerged as a brilliant but flawed man who amassed a fabled fortune as well as considerable power, but would have given it up in a heartbeat for the woman he loved.

It became obvious that I had stumbled upon the material for a book. Although I had edited a great many books written by other people, I had never planned to inflict one of my own on the world, being more than happy to remain on the other side of the publishing fence. But I found I couldn’t ignore this story which kept me awake at night, so I started rising at six, to spend a couple of hours writing before leaving for the office. It was hard going, and on dark winter mornings it took every ounce of willpower to drag myself out of bed. I soon discovered – perhaps surprisingly, given my professional background – that I had little idea how to go about actually writing a book. So I signed up for an evening class in ‘Writing Family History’, and it was here that I had another stroke of luck – for the teacher turned out to be the acclaimed biographer Andrea Stuart, who was then at work on Sugar in the Blood, the story of her ancestors in Barbados, black and white. One Saturday morning, she took us on a tour of the National Archives at Kew, a vast concrete behemoth where we were inducted into the practicalities of archival research; it was time well spent, for I would become a frequent visitor over the next few years. Andrea encouraged me, at a stage when I really needed it, to pursue my own embryonic Jamaican story.

I look back on this as a strange, transitional period in my life; I felt like a kind of time-travelling commuter, secretly shuttling back and forth between the present day and the world of my eighteenth-century family. It was exciting, certainly, but also emotionally challenging, as I struggled to reconcile my inborn sympathy for these people, my ancestors, with their activities in Jamaica. I was never so naive as to imagine that those activities might be unconnected with slavery, but nor was I fully prepared for the degree to which they were involved. It was not a pleasant discovery.

My eyes were opened, too, to the nature of Britain’s culpability. I learned that there were thousands of well-to-do Georgian families, like mine, whose wealth and prestige had derived from the blood, sweat and lives of enslaved Africans. Moreover, individuals from every rank of society had played their part in propping up slavery, from the royal personages who sanctioned the slave trade with West Africa in the first place, to the sailors who crewed the slave ships – even the ordinary working people who consumed the tainted sugar. Here in Britain, we have tended to keep this disturbing aspect of our national story at arm’s length; unlike the United States, where its divisive consequences are plain to see, slavery was not commonplace on these shores. We proudly celebrate our great abolitionists, of course, but we would rather not know too much about what they were campaigning to abolish.

Sometimes, after yet another grim discovery in the archives, I wondered what kind of fool would knowingly implicate his own family by writing them into this shocking chapter of history. Yet my instinct told me to press on; in fact, I felt a powerful responsibility to do so. Clearly I could make no amends for my ancestors’ misdeeds – but I could certainly attempt to make something positive out of what they had left behind. Since this mostly consisted of old letters, to tell their story made perfect sense to me. But it was essential that I should write it warts-and-all. ‘Do not try and make all the ancestors goody two shoes when some were plainly not,’ advised David Atkinson, whose messages were a tonic for my sometimes flagging spirits. ‘Detach yourself – you have every right to portray some as villains, some as “not sures”, some as feckless and some as the heroes. I suspect you might be torn on this – don’t be. You have my blessing to treat some of them hard.’

To have my newfound cousins cheering me on was just what I needed as I embarked on a long voyage into our ancestors’ past – one that took me all the way from London to the abandoned sugar plantations of Jamaica. But all roads ultimately led to Temple Sowerby, where so many Atkinsons were born and so many are buried. Their tangled inheritance may have scattered them around the world, but the evidence made its way back to that weather-beaten house in the shadow of the Pennines and, eventually, in the form of the curious miscellany of relics and papers that were my inheritance, into my hands.

TWO

The Tanner’s Wife

THE RIVER EDEN carves a sinuous line down the valley that bears its name, past ruined castles and ruminating cows, swelling from the countless becks that drain off steep fells; by the time it flows under the red sandstone bridge at Temple Sowerby, it has completed almost half its ninety-mile journey. Cross Fell, highest of the Pennine hills, dominates the skyline at this point; it enjoys the rare distinction of harbouring a breeze with so much bluster that it has its own name. ‘A violent roaring hurricane comes tumbling down the mountain, ready to tear up all before it,’ was how one eighteenth-century traveller described the ‘Helm’ wind.[1]

From the summit of Cross Fell – assuming the absence of its usual cloud cap – you can see the hills of Galloway in southern Scotland. Two thousand years ago, the Romans built a wall to keep out the Caledonian people to the north, and legions of soldiers marched through Temple Sowerby on their way to forts along its route; a Roman milestone can be found in a layby just outside the village, although its inscription weathered away aeons ago. Scandinavian immigrants settled in the area during the ninth century. These hardy people left their linguistic imprint across northern England, not just in the words that evoke its landscape – beck and fell are of Norse origin – but also in its place names. Sauerbi is old Norse for ‘farmstead on sour ground’. Even the Vikings, it seems, saw Temple Sowerby as a hardship post.

The first tangible evidence of the Atkinsons of Temple Sowerby can be found in the basement of the county offices at Kendal – this is where the records are kept for the historic county of Westmorland, which was absorbed into Cumbria in 1974. William Atkinson – my nine-times great-grandfather – was one of seventeen yeomen who in 1577 were granted thousand-year leases on their land in the village, along with ‘reasonable common for the pasturing of their cattle’, by the lord of the manor, Christopher Dalston.[2] It feels only fitting that I should examine the legal document in which my ancestors’ earliest property rights were enshrined, but the large sheet of vellum is a brute to unfold, so defiantly springy that it resists my attempts to flatten it out. I must be firm with it, I realize, but not too firm, since the archivist is watching me like a hawk.

Eventually, after wrestling with it for a minute or two, I have it spreadeagled on the desk, its corners pinned down with iron weights. I now appreciate why calfskin has always been the material upon which parliamentary laws are recorded, for the document remains in superb condition, apart from two holes caused either by rodents or fire – it’s hard to tell which. Next comes a still greater challenge – deciphering the script. At first I hold out little hope of being able to read the spiky Elizabethan handwriting. But soon I find that if I stare at them in an abstract way, shapes start to turn into words.

This lease marks the culmination of a conflict that simmered in Temple Sowerby for twenty years. Until the dissolution of the monasteries in the 1530s, the manor was held by the religious orders of the Knights Templar (who gave it their name), and then by the Knights Hospitaller, both of whom interfered little in the lives of the villagers. That all changed in 1543 when the Dalston family acquired the manor from the Crown. It was inevitable the tenants of Temple Sowerby would resent their first resident landlords in nearly four centuries, especially given that both Thomas Dalston and his son, Christopher, made it plain that they intended to claim the common land for themselves. William Atkinson was one of eight villagers who filed a writ against Christopher Dalston in 1559. Their case was rejected by the Lord President of the North at York; next, they took it to Court of Chancery in London.

The 1577 lease was the upshot of this litigation. Dalston gained exclusive use of half the common, and was ordered to grant his tenants possession of the other half. For their part, the villagers undertook to use Dalston’s mill at Acorn Bank to grind their flour, and to pay for half of any necessary repairs. Although it was technically a compromise, they nonetheless saw the agreement as a victory against their overbearing lord. Christopher Dalston only conceded to these terms ‘because he would be of quietness with the plaintiffs and no further be molested as he by a long time hath been’.[3] He never forgave his tenants their insolence; and they in turn fully reciprocated his ill feelings.

The first mention of the leather-tanning business that kept the Atkinson family busy for at least five generations is found in the will of William Atkinson, second son of William who signed the 1577 agreement. This William never married, and on his death in 1645 he left his elder brother John ‘all my leather tubbes and barke and my apparel the bedstead I lye in and one feather bed and one nagge’.[4]

Temple Sowerby was well positioned for the trade in animal skins, being on a major cattle-droving route. Every year, between April and October, thousands of black cows funnelled through the village on their way from the breeding grounds of south-west Scotland to Smithfield market in London; plenty failed to last the distance, falling by the wayside due to lameness or sickness. The ‘drovers’ who herded cattle were tough individuals, and Westmorland was the harshest terrain they would cross – Daniel Defoe in 1724 described the county as ‘eminent only for being the wildest, most barren, and frightful of any that I have passed over in England, or in Wales’.[5] At Temple Sowerby the drovers found a range of services, including a farrier for shoeing horses and cows, two inns and ample pasturage.

Two tanyards lay at a slight remove from the centre of the village – necessarily so, given the stench arising from the tanning process. First, any decaying flesh was cleaned off the raw hides, and any hair removed; next came the stage known as bating, during which the skins were softened in an ammoniac brew of watered-down pigeon shit shovelled from a large dovecote on site. They were then immersed in a succession of clay-lined pits filled with tanning liquor of increasing strength, the active ingredient being the tannin released by ground-up dried oak bark steeped in water. The overall length of the soak determined the toughness of the finished product, but generally lasted a year or more. Finally the cured skins were trimmed, shaved, greased, dyed, rolled, buffed and prepared for market. So many of life’s necessities – belts, boots, buckets, harnesses, pouches, saddles, straps and trunks – were fashioned from leather. Its manufacture was by no means a noble activity; but it was a vital one.

THE HEARTH TAX return of my seven-times great-grandfather John Atkinson for 1670 declares just one fireplace – compared to Squire Dalston’s nine at Acorn Bank.[6] John died in 1680, and what little I know of him comes from his will, a document noteworthy as the first (but by no means the last) record of friction within the Atkinson family.

The declarative language of John’s will suggests it was dictated on his deathbed, the rather melodramatic custom of the day. So close to his final breath, you would hope that John might be making his peace with the world, but it seems he felt the need to mediate between his squabbling offspring. Thus, having apportioned his earthly possessions – he left forty shillings a year to his daughter Barbara, and the bulk of any ‘goods and lands moveable and unmoveable’ to his son George – John went on to specify some conditions. As long as she remained unmarried, Barbara was to be housed by her brother. ‘If the sayd Barbry and Geordge cannot agre,’ John went on, ‘Geordge is to builde hir a chimley in the backe chamber and she is to live theire and if the sade chamber doe fall to decay then Geordge is to repare the same of his owne cost.’[7] Barbara never did marry, and I haven’t been able to discover whether that extra chimney was ever needed. But when George died more than forty years later he left his sister £5 – so perhaps they managed to agree after all.

As I write, George’s Latin textbook sits on the desk before me – it’s the oldest object I own. Bound in scuffed calfskin, it contains almost five hundred handwritten pages of Latin grammar and syntax. Like the thousand-year lease, the script is in a distinctively Elizabethan hand, which is confirmed by the date: ‘anno domini 1595’. For George, too, the book was a hand-me-down, as it predates his schooldays by several generations. Born in 1657, he was a pupil in the early 1670s, by which time the writing style had become rounder and, to modern eyes, much more legible. So how do I know that the book once belonged to him? The impulse to deface textbooks is hard-wired into every small boy’s brain. George was no exception, and he wrote his name a few times on the flyleaf, along with this enjoyable doggerel: