Ecosociology Sources. Series: «Ecosociology»

This approach was enhanced by the fact that such socio-ecological methods as zoning and social mapping were successfully used for identifying and verifying the correlation between various social variables, which at first glance were not interrelated. Moreover, the use of these methods and conceptual approaches made possible generalized descriptions of various multi-variable cases, giving at least an understanding of functional, if not causal dependence.

An effective use of the socio-ecological method can be also explained by the level-based approach, which is similar to the principle used in system analysis when the phenomenon of a local community (social organism) being examined is analyzed in its interrelation with its higher (macro) and lower (micro) level. The lower level is the individual and the higher level is represented by social “compositions” consisting of various communities united into municipalities.

However, causal links of social organisms with their habitat and issues relating to optimal life support were not yet studied by ecosociology. Therefore, beginning with the mid-1930s, the abstract character of the ecosociology’s space-temporal functionalism came under criticism from representatives of the socio-cultural school, who emphasized the dependence of natural resource use on cultural traditions, values, symbols and norms.

Milla Aissa Alihan proposed a new vision of society and started working on a methodology for analyzing the social sphere within the framework of the already existing discipline – urban sociology. Three main variables – social standing (status), urbanization level (population density) and degree of segregation (multiplicity of social groups) – were identified. A city was described as a subsystem comprising greater territories and larger communities. In doing so, researchers were using data obtained from a census of urban population. On the one hand, this allowed analysis of cities rather than urban communities. On the other hand, this made possible, based on the statistical data received, a classification of subsystems (local communities). The result obtained could be rechecked some time later (sociological monitoring) to see social dynamics. This also enabled researchers to reasonably theorize on social organization as the main result of evolution19.

Amos Henry Hawley (1910—2009), further developing the socio-ecological concept, was of the opinion that a community is an ecosystem (a territorial local system of interrelations between its functionally differentiated parts). Ecosociology may view a community as a population united by the similarity of its component organisms (commensalism). Human population is included into the ecosystem due to a mutually useful interaction with dissimilar organisms (symbiosis).

The focus of attention of the researcher-sociologist now turns to the functional socio-ecological system that develops in the process of interaction with an abiotic environment and other biotic communities. During such interaction, a specific social organization with specific characteristics is formed20. Despite the fact that a civilized man prefers adapting nature to his needs rather than adapts to nature, and tries to irreversibly change nature’s characteristics and processes for his benefit, nature has resilience and is capable of influencing humans. It also can perform irreversible acts on humans.

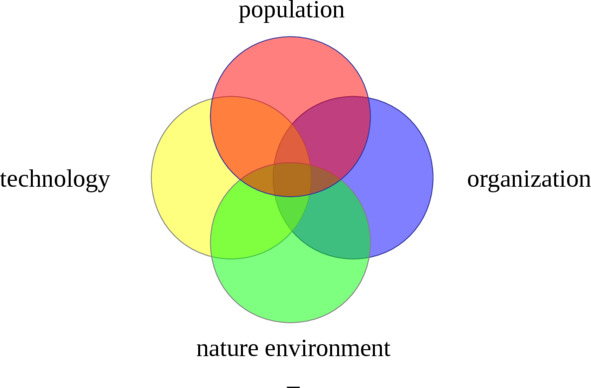

Finally, as the socio-ecological theories, approaches and methods are developed, social atomism is substituted with organizational functionalism; attention is focused more on the functioning of a social organization rather than on the driving forces and causes of this process or space-temporal forms of its manifestation. A description of this mechanism was made by Otis Dudley Duncan (1921—2004) and Leo Francis Schnore, who used the socio-ecological complex theory. The socio-ecological complex comprises four components:

1) Population (local human population);

2) Nature environment (abiota + biota + human populations);

3) Technology (things + means of production + culture of production);

4) Organization (social institutes and structures)21.

Schema: Social ecological complex

Park proposed an analogous structure of the socio-ecological process and studies of movement in time and space (communication and migration) as well as unique events (artefacts) determined by culture. Duncan and Schnore focused on the functioning of social organization, believing that this component was of most importance for their research. Making a social organization the subject of their analysis within the framework of ecosociology, they used quantitative methods and, based on the data obtained, proposed a thesis that it is a collective adaptation of the human population to the environment.

This approach was also different from that proposed by Park, where the population of a city, state, country and planet represented the macro level. A new understanding of the socio-ecological process as the functioning of a social organization allowed ecosociologists to conclude that samples of interactions that provide an ecological niche for the community, are the analytical unit. Therefore, society was viewed as a human population that was trying to use the environment’s resources to preserve itself (survive) through adaptation.

However, understanding the importance of the space-temporal linking of the social organization’s interactions being described and analyzed, ecosociologists were yet unwilling to use physical characteristics of the natural environment for their analysis. This was due to an observation that the physical environment in cities is much technologized and designed to suit the needs of humans rather than the biota.

Accordingly, in cities, the main impact on human population is made by the social environment, which replaces the natural environment. Ecosociologists then described and interpreted social phenomena using biological terms as “predatory”, “parasitic”, “dominating” and “symbiotic” relationships. This method was to socialize and defend the independence of their discipline.

The approach taken by Duncan and Schnore was perceived as oppositional to other approaches to studying the social organization, namely, the culturological and behaviorist approaches. However, this was an opposition to the constructivist approach that used new but already proven tools and methods of research that were getting closer to an explanation of social reality.

Sociologists-culturologists tended to make descriptions or analyses, starting and ending with social sphere, without any space-temporal linkage. Sometimes, they did use the word “nature”, not in the sense of nature proper but intending to emphasize an unconditional, inborn, natural quality of a social objects or subject.

For ecosociology, explanations offered by behaviorists were considered unacceptable at the macro level because no individual and collective human behavior existed at this level. At the macro level, interaction was limited to social institutes and structures (consisting of organizations) in the context of climatic zones, continents and other major space-temporal natural formations.

There was no way of determining social organization via neither existing cultural conditions nor social-psychological behavior-related affirmations. The new methodology proposed by ecosociologists enabled a breakthrough in studying the phenomena of human behavior and culture. The principle of functional interaction of the environment and social organization, as well as the well-developed conceptual framework of biology made ecosociology popular but could not be used for getting closer to explaining many causes of human interactions.

However, sociology and other humanitarian disciplines recognized that the physical environment can and does influence society and human behavior. Therefore, sociology branched out into the old “traditional” sociology, which maintained that social facts could be explained only with other social facts, and a new environmental (ecological) sociology.

Traditional sociology, using a sociologism-based approach, developed an attitude to inter-disciplinarity, which looked more as a ban on mentioning physical and biological environment. There also existed a disciplinary ban on status accounting for ecosystems and the consequences of their impact on humans and human communities. Violators, labeled as naturalists, were shunned by sociologists, who refused to quote or even notice them. Despite this, in the first half of the 20th century, several sociological works, linking human activity to the environment, were published.

Radha Kamal Mukherjee (1889—1968) was one of the first to conduct inter-disciplinary studies in the field of regional ecology within the framework of the sociology of labor. This research was done in India, a country different from the United States in many specific aspects22.

Pitirim Aleksandrovich Sorokin (1889—1968) in his book “Man and society in calamity” summarizes almost 25 years of observations of social catastrophes, ranking epidemics and hunger together with revolutions and wars23. He links social degradation and crises to natural calamities and catastrophes, which always go hand in hand.

Paul Henry Landis (1901—1985), within the framework of rural sociology studied miner’s communities and their social structure, linking cultural change in these communities to accessibility and richness of natural resources and other factors of the natural environment24.

Fred Cottrell, in his studies of industrial sociology, analyzed interrelations between cultural forms of society and forms of energy. He concluded that the human civilization directly depends on technology and kinds of energy being used, showing the path of evolution from antiquity to the nuclear age, progress made by society and the resulting influence of economic, moral and social aspects. The issues relating to generation, transformation, distribution and consumption of energy remain one of the most serious issues over the entire history of civilization25.

In the late 1960s – early 1970s, this gave rise to the following three organizational changes, which made possible further strengthening of ecosociology as a sub-discipline of sociology:

1) An informal group of sociologists, studying interactions as related to natural resources and natural resource use, splintered from the Society for Studies of Rural Problems;

2) The Society for Studies of Social Issues established a division for research of environmental issues;

3) The American Sociological Association established a committee for ecosociology. The main subjects of ecosociological research were natural resource management, recreation in wild nature, ecological movement and public opinion on ecological problems.

Ecosociology saw its practical tasks as being elaboration of models and programs for restoring the quality of the natural environment. This pragmatism ensured strong financial support for the research from interested business and the authorities. This allowed expanding the scope of socio-ecological approach, provided new explanations of causes behind typical interactions of society with the natural environment, including erroneous interactions fraught with adverse consequences for humanity and nature.

New environmental paradigm

Social situation changed in the early 1970s. Environmental awareness became the cause and source of more active ecological ideas not only in sociology but also in the international community. The discourse comprised with such notions as “environmental pollution”, “deficit of natural resources”, “overpopulation”, “negative consequences of urbanization”, “extinction of species”, “degradation of landscapes and desert advancing”, “dangerous climate changes leading to natural catastrophes” and so on. All these phenomena are now recognized as being socially significant due to their influence on the development of not only local communities but also the international community. As a result, they acquire a trans-local parameter.

Ecosociologists never missed the chance to highlight the existence of two main problems of the sociological disciplinary tradition, namely, the Durkheim sociologism and the Weber tradition of studying a single act and its significance for the individual. However, sociologists-traditionalists completely ignored the space-temporal, physiological, psychological and biological characteristics.

William Robert Catton (1926—2015) and Riley E. Dunlap proposed a “new environmenta0l paradigm”. It constituted a new stage of socio-ecological research and theorizing characterized by an interdisciplinary approach26. The new environmental paradigm identifies two periods in the development of the sociological theory27. The first one encompasses everything corresponding to the “paradigm of human exceptionalism”, which preceded the second period. The first one encompasses everything corresponding to the “human exceptionalism paradigm”, which preceded the second period. The second period relates to the emergence of the new environmental paradigm – the paradigm of human emancipation.

Referring to the preceding theories, environmentalists characterize them as anthropocentrism, social optimism and anti-ecologism. They emphasize that these are more than just theories but a way of thinking and a “modus vivendi”. Adverse socio-ecological consequences of the preceding period could be dealt with if the environmental (ecological) initiative becomes a mass movement and switches from anthropocentric consciousness to ecological one.

Older theories maintain that the socio-cultural factors are the main determinants of human activity, and culture makes the difference between a human and an animal. With the socio-cultural environment being the determinant context of interaction, the biophysical environment became somewhat alienated. Bearing in mind the cumulativeness of culture, social and technological progress may continue indefinitely. This is followed by an optimistic conclusion that all social problems can be resolved. The new environmental paradigm proclaims a new social reality:

– Humans are not the dominant species on the planet;

– Biologism of humans is no radically different from the other living creatures also being part of the global ecosystem;

– Humans are not free to choose their fate as they please, as it depends on many socio-natural variables;

– Human history is not a history of progress, which to a certain extent enhances adaptive capability, but a history of fatal errors, crises and catastrophes resulting from unknown causes and scarcity of natural resources.

The new environmental paradigm does show an understanding that humans are not exclusive specie but specie with exclusive qualities – culture, technology, language and social organization. In general, the new environmental paradigm is based on the postulate that, in addition to genetic inheritance, humans also have a cultural heritage and are hence different from the other animal species. In this, the new paradigm continues the tradition of the old paradigm of human exceptionalism.

Besides, even those sociologists, who did not subscribe to the new environmental paradigm, pointed out a traditional omission: society is not really exploiting ecosystems in order to survive but is rather trying to overexploit the natural resources for the sake of its prosperity, thus undermining the ecosystem’s stability, and may eventually destroy the natural base that makes human existence possible. This dilemma, initially posed within the framework of the new environmental paradigm, turned out to be so serious that representatives of other social sciences joined the debate.

Herman Edward Daly, within the framework of the economic sciences, presented the theory of a steady state economy, thus making a scientific contribution to the sustainable development concept, and participated in establishing the “International Society for Environmental Economics”28.

William Ophuls, in his political studies, called for a new ecological policy while denying the very possibility of sustainable development. This assumption was based on forecasts of quick depletion of the planetary reserves of fossil fuel. In the end, under the laws of thermodynamics and due to inexorable biological and geological constraints, civilization is doomed. In his opinion, this was already obvious, given the rising tide of socio-ecological, cultural and political problems29.

Donald L. Hardesty, who specialized in ecological anthropology, a subject area of the anthropological science, studied miner’s communities, the history of their cultural change, public living conditions, gender strategies and so on. He monitored how these communities were transforming the natural landscape into a cultural one, pointing out the accompanying process of toxic waste generation30.

Allan Schnaiberg (1939—2009), within the framework of the sociology of labor, opined that social inequality and production race (“the treadmill of production” theory) were the main causes of anthropogenic environmental issues. From the Neo-Marxist positions, he criticized all “bourgeois” authors who were showing at least some optimism regarding the possibility of peaceful resolution of the socio-ecological problems (other than through class struggle and a change in the social relations of production)31.

John Zeisel, within the framework of the sociological theories of architecture, paid attention to important hands-on aspects relating to interaction of humans with the natural environment, believing that psychic, physical and psychosomatic peculiarities of people of different age require different architectural solutions32.

Ecosociology now included the notions of an ecological complex and an ecosystem, considering the natural environment as a factor influencing the behavior of humans and society. One might say that ecosociology analyzes interaction between the physical (natural) environment and society. To perceive all forms of interaction between humans / society and the natural environment, it was proposed that organizational forms of human collectives, their cultural values and composition had to be taken into account.

Therefore, the natural environment influences all stages of Park’s social evolution and elements of the ecological complex proposed by Duncan and Schnore – population, technology, culture, social system, and the individual. In this context, the basic questions posed by ecosociology were: How can different combinations of all the above elements influence the natural environment? And how can one ensure effective change in the natural environment when these elements are modified?

Foreign authors of environmental theories

An important issue in ecosociology related to rethinking of the notion “environment”. By this, traditional sociology meant the social environment while ecosociology primarily meant the natural or biophysical environment. This division took some time to be accepted by all sociologists.

In addition, ecosociology made an attempt to go beyond the vision of a symbolic or cognitive interaction between the man and the environment. Ecosociologists were trying to prove that the surrounding natural conditions – such as air and water pollution, waste generation, erosion and depletion of soil, spillages of oil and so on – in addition to a symbolic effect, have a direct, non-symbolic impact on human life and social processes. This meant that, besides the impact made by polluted air and urbanized landscape on people’s perception of the same, one had to take into account the influence of this factor on physical human health when studying social mobility, and mental health – when studying deviant behavior.

In the 1970s, according Franklin D. Wilson, the focus of attention of social ecology and ecosociology shifted to the following issues: interaction of humans and the artificial (“built”) environment; organizational, industrial, state responsibility for environmental issues; natural perils and catastrophes; assessment of environmental impact; impact from scarcity of natural resources; issues relating to deployment of scarce natural resources and carrying capacity of natural environment33.

Ecosociologists also noted the increasing influence of that part of public movement, which was showing concern over the state of natural environment and propagated such values as an environmentally friendly lifestyle and shaping a new ecological awareness, on social processes and institutes. These people were somewhat different from the environmental movement due to a greater emphasis on developing an ecological behavior and inner human potential (deep ecology). This difference is explained by the fact that these people were participants of other public movements and adherents of new religions rather than of the ecological movement per se.

Murray Bookchin (1921—2006), the main ideologist of ecoanarchism, studied social ecology-related issues, criticizing biocentric theories of deep ecologists and sociobiologists, as well as the followers of post-industrial ideas about the new epoch34. He and other authors believed that a socio-ecological crisis was inevitable wherever state authority existed. All forms of governance are violence of man against man and nature.

In the opinion of ecoanarchists, a global ecological crisis could be prevented via decentralization of society and abandonment of large-scale industrial production. All people were to stop working for transnational corporations, move from metropolitan cities to small towns, rural municipalities, small communes and communities. Social relationships were to be regulated by methods of direct democracy and governed by direct right to life and natural resource use.

In the late 1990s, Bookchin refused to call himself an ecoanarchist, probably after seeing the implementation of his ideas in rural ecoanarchist communities and assuring himself that these ideas were inviable due to the impossibility of collective action and self-sufficiency, breakup and reverse migration to the cities caused by inequality and violence.

David Pepper, the ideologist of ecosocialism, and other authors were positive that the main causes of the socio-ecological crisis were the capitalist mode of production where society only exploited natural resources without producing them. In contrast with ecoanarchists, they suggested centralization of management (in the form of a state-controlled socialist economy), which was to help preserve nature as a universal human value35.

In the 1980s, these ideas were still popular but radical socio-ecological reforms were no longer associated with major social change. Instead, they were associated with internal change in the individual and society, a change in the system of values and attitude to nature. They proposed to renounce anthropocentrism and replace it with biocentrism.

Arne Dekke Eide Naess (1912—2009) and other authors promoted the idea of deep ecology, suggested distinctions between social and natural, holism instead of dualism, i.e., the unity of man and nature, society and the environment. Homo economicus was to make way for homo ecologicus, a bearer of ecological consciousness, which, in the transitional era of ecological crises and catastrophes, was to be cultivated and developed. After that, all artificial boundaries (ideological, state, religious, race, cultural, gender, biological) were expected to collapse, and a New Age would begin36.

As already mentioned above, ecosociologists also responded to the ongoing social change, proposing the new ecological paradigm, under which the paradigm of human exceptionalism would be replaced by that of human emancipation. These ideas were extremely popular among younger people and public movements addressing the issues relating to the quality of life. The power, industrial and financial elites could propose no viable alternative. Children saw no future in the activities of their parents. Society was afraid that it was edging towards a catastrophe and extinction. This situation could not last for a sufficiently long time and an intellectual breakthrough was needed.