Royal Edinburgh: Her Saints, Kings, Prophets and Poets

It would appear, however, that little could be done against the immediate head of that great house, and the two rulers, though they had made friends over this common object, had to await their opportunity, and in the meantime do their best to maintain order and to get each the chief power into his own hands. Crichton found means before very long to triumph over his adversaries in his turn by rekidnapping the little King, for whom he laid wait in the woods about Stirling, where James was permitted precociously to indulge the passion of his family for hunting. No doubt the crafty Chancellor had pleasant inducements to bring forward to persuade the boy to a renewed escape, for "the King smiled," say the chroniclers, probably delighted by the novelty and renewed adventure—the glorious gallop across country in the dewy morning, a more pleasant prospect than the previous conveyance in his mother's big chest. Thus in a few hours the balance was turned, and it was once more the Chancellor and not the Governor who could issue ordinances and make regulations in the name of the King.

Nothing, however, could be more tedious and trifling in the record than these struggles over the small person of the child-king. But the story quickens when the long-desired occasion arrived, and the two rulers, rivals yet partners in power, found opportunity to strike the blow upon which they had decided, and crush the great family which threatened to dominate Scotland, and which was so contemptuous of their own sway. The great Earl, Duke of Touraine, almost prince at home, the son of that Douglas whose valour had moved England, and indeed Christendom, to admiration, though he never won a battle—died in the midst of his years, leaving behind him two young sons much under age as the representatives of his name. It is extraordinary to us to realise the place held by youth in those times, when one would suppose a man's strength peculiarly necessary for the holding of an even nominal position. Mr. Church has just shown in his Life of Henry V how that prince at sixteen led armies and governed provinces; and it is clear that this was by no means exceptional, and that the right of boys to rule themselves and their possessions was universally acknowledged and permitted. The young William, Earl of Douglas, is said to have been only about fourteen at his father's death. He was but eighteen at the time of his execution, and between these dates he appears to have exercised all the rights of independent authority without tutor or guardian. The position into which he entered at this early age was unequalled in Scotland, in many respects superior to that of the nominal sovereign, who had so many to answer to for every step he took—counsellors and critics more plentiful than courtiers. The chronicles report all manner of vague arrogancies and presumptions on the part of the new Earl. He held a veritable court in his castle, very different from the semi-prison which, whether at Edinburgh or Stirling, was all that James of Scotland had for home and throne—and conferred fiefs and knighthood upon his followers as if he had been a reigning prince. "The Earl of Douglas," says Pitscottie, "being of tender age, was puffed up with new ambition and greater pride nor he was before, as the manner of youth is; and also prideful tyrants and flatterers that were about him through this occasion spurred him ever to greater tyranny and oppression." The lawless proceedings of the young potentate would seem to have stirred up all the disorderly elements in the kingdom. His own wild Border county grew wilder than ever, without control. Feuds broke out over all the country, in which revenge for injuries or traditionary quarrels were lit up of the strong hope in every man's breast not only of killing his neighbour, but taking possession of his neighbour's lands. The caterans swarmed down once more from the mountains and isles, and every petty tyrant of a robber laird threw off whatever bond of law had been forced upon him in King James's golden days. This sudden access of anarchy was made more terrible by a famine in the country, where not very long before it had been reported that there was fish and flesh for every man. "A great dearth of victualls, pairtly because the labourers of the ground might not sow nor win the corn through the tumults and cumbers of the country," spread everywhere, and the state of the kingdom called the conflicting authorities once more to consultation and some attempt at united action.

The meeting this time was held in St. Giles's, the metropolitan church, then, perhaps, scarcely less new and shining in its decoration than now, though with altars glowing in all the shadowy aisles and the breath of incense mounting to the lofty roof. There would not seem to have been any prejudice as to using a sacred place for such a council, though it might be in the chapter-house or some adjacent building that the barons met. It is to be hoped that they did not go so far as to put into words within the consecrated walls the full force of their intention, even if it had come to be an intention so soon. There was but a small following on either side, that neither party might be alarmed, and many fine speeches were made upon the necessity of concord and mutual aid to repress the common enemy. The Chancellor, having restolen the King, would no doubt be most confident in tone; but on both sides there were equal professions of devotion to the country, and so many admirable sentiments expressed, that "all their friends on both sides that stood about began to extol and love them both, with great thanksgiving that they both regarded the commonwealth so mickle and preferred the same to all private quarrels and debates." The decision to which they came was to call a Parliament, at which aggrieved persons throughout the country might appear and make their complaints. The result was a crowd of woeful complainants, "such as had never been seen before. There were so many widows, bairns, and infants seeking redress for their husbands, kin, and friends that were cruelly slain by wicked murderers, and many for hireling theft and murder, that it would have pitied any man to have heard the same." This clamorous and woeful crowd filled the courts and narrow square of the castle before the old parliament-hall with a murmur of misery and wrath, the plaint of kin and personal injury more sharp than a mere public grief. The two rulers and their counsellors no doubt listened with grim satisfaction, feeling their enemy delivered into their hands, and finding a dreadful advantage in the youth and recklessness of the victims, who had taken no precaution, and of whom it was so easy to conclude that they were "the principal cause of these enormities." Whether their determination to sacrifice the young Douglas, and so crush his house, was formed at once, it is impossible to say. Perhaps some hope of moulding his youth to their own purpose may have at first softened the intention of the plotters. At all events they sent him complimentary letters, "full of coloured and pointed words," inviting him to Edinburgh in their joint names with all the respect that became his rank and importance. The youth, unthinking in his boyish exaltation of any possibility of harm to him, accepted the invitation sent to him to visit the King at Edinburgh, and accompanied by his brother David, the only other male of his immediate family, set out magnificently and with full confidence with his gay train of knights and followers—among whom, no doubt, the youthful element predominated—towards the capital. He was met on the way by Crichton—evidently an accomplished courtier, and full of all the habits and ways of diplomacy—who invited the cavalcade to turn aside and rest for a day or two in Crichton Castle, where everything had been prepared for their reception. Here amid all the feastings and delights the great official discoursed to the young noble about the duties of his rank and the necessity of supporting the King's government and establishing the authority of law over the distracted country, sweetening his sermon with protestations of his high regard for the Douglas name, whose house, kin, and friends were more dear to him than any in Scotland, and of affection to the young Earl himself. Perhaps this was the turning-point, though the young gallant in his heyday of power and self-confidence was all unconscious of it; perhaps he received the advice too lightly, or laughed at the seriousness of his counsellor. At all events, when the gay band took horse again and proceeded towards Edinburgh, suspicion began to steal among the Earl's companions. Several of them made efforts to restrain their young leader, begging him at least to send back his young brother David if he would not himself turn homeward. "But," says the chronicler, "the nearer that a man be to peril or mischief he runs more headlong thereto, and has no grace to hear them that gives him any counsel to eschew the peril."

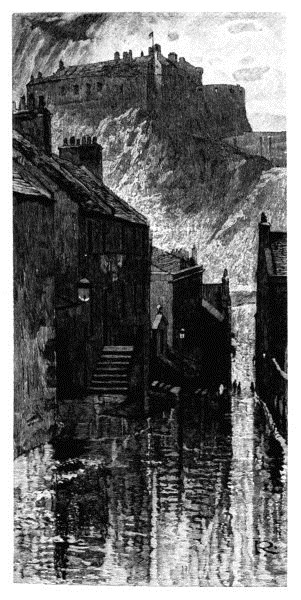

EDINBURGH CASTLE FROM THE VENNEL

The only result of these attempts was that the party of boys spurred on, more gaily, more confidently than ever, with the deceiver at their side, who had spoken in so wise and fatherly a tone, giving so much good advice to the heedless lads. They were welcomed into Edinburgh within the fatal walls of the Castle with every demonstration of respect and delight. How long the interval was before all this enthusiasm turned into the stern preparations of murder it seems impossible to say—it might have been on the first night that the catastrophe happened, for anything the chroniclers tell us. The followers of Douglas were carefully got away, "skailled out of the town," sent for lodging outside the castle walls, while the two young brothers were marshalled, as became their rank, to table to dine with the King. Whether they suspected anything, or whether the little James in his helpless innocence had any knowledge of what was going to happen, it is impossible to tell. The feast proceeded, a royal banquet with "all delicatis that could be procured." According to a persistent tradition, the signal of fate was given by the bringing in of a bull's head, which was placed before the young Earl. Mr. Burton considers this incident as so picturesque as to be merely a romantic addition; but no symbol was too boldly picturesque for the time. When this fatal dish appeared the two young Douglases seem at once to have perceived their danger. They started from the table, and for one despairing moment looked wildly round them for some way of escape. The stir and commotion as that tragic company started to their feet, the vain shout for help, the clash of arms as the fierce attendants rushed in and seized the victims, the deadly calm of the two successful conspirators who had planned the whole, and the pale terrified face of the boy-king, but ten years old, who "grat verie sore," and vainly appealed to the Chancellor for God's sake to let them go, make one of the most impressive of historical pictures. The two hapless boys were dragged out to the Castle Hill, which amid all its associations has none more cruel, and there beheaded with the show of a public execution, which made the treachery of the crime still more apparent; for it had been only at most a day or two, perhaps only a few hours, since the Earl and his brother in all their bravery had been received with every gratulation at these same gates, the welcome visitors, the chosen guests, of the King. The populace would do little but stare in startled incapacity to interfere at such a scene; some of them, perhaps, sternly satisfied at the cutting off of the tyrant stock; some who must have felt the pity of it, and had compunction for the young lives cut off so suddenly. A more cruel vengeance could not be on the sins of the fathers, for it is impossible to believe that the Regents did not take advantage of the youth of these representatives of the famous Douglas race. Older and more experienced men would not have fallen into the snare, or at all events would have retained the power to sell their lives dear.

If the motives of Livingstone and Crichton were purely patriotic, it is evident that they committed a blunder as well as a crime: for instead of two boys rash and ill-advised and undeveloped they found themselves in face of a resolute man who, like the young king of Israel, substituted scorpions for whips, persecuting both of them without mercy, and finally bringing Livingstone at least to destruction. The first to succeed to William Douglas was his uncle, a man of no particular account, who kept matters quiet enough for a few years; but when his son, another William, succeeded, the Regents soon became aware that an implacable and powerful enemy, the avenger of his two young kinsmen, but an avenger who showed no rash eagerness and could await time and opportunity, was in their way. The new Earl married without much ceremony, though with a papal dispensation in consequence of their relationship, the little Maid of Galloway, to whom a great part of the Douglas lands had gone on the death of her brothers, and thus united once more the power and possessions of his name. He was himself a young man, but of full age, no longer a boy, and he would seem to have combined with much of the steady determination to aggrandise and elevate his race which was characteristic of the Douglases, and their indifference to commonplace laws and other people's rights, an impulsiveness of character, and temptation towards ostentation and display, which led him at once to submission and to defiance at unexpected moments, and gave an element of uncertainty to his career. Soon after his succession it would seem to have occurred to him, after some specially unseemly disputes among some of his own followers, that to get himself into harmony with the laws of the realm and gain the friendship of the young King would be a good thing to do. He came accordingly to Stirling where James was, very sick of his governors and their wiles and struggles, and throwing himself at the boy's feet offered himself, his goods and castles, and life itself, for the King's service, "that he might have the licence to wait upon His Majesty but as the soberest courtier in the King's company," and proclaimed himself ready to take any oath that might be offered to him, and to be "as serviceable as any man within the realm." James, it would seem, was charmed by the noble suitor, and all the glamour of youth and impulse which was in the splendid young cavalier, far more great and magnificent than all the Livingstones and Crichtons, who yet came with such abandon to the foot of the throne to devote himself to its service. He not only forgave Douglas all his offences, but placed him at the head of his government, "used him most familiar of any man," and looked up to him with the half-adoring admiration which a generous boy so often feels towards the first man who becomes his hero.

This happened in 1443, when James was but thirteen. It would be as easy to say that Douglas displaced with a rush the two more successful governors of the kingdom, and took their places by storm—and perhaps it would be equally true: yet it would be vain to ignore James as an actor in national affairs because of his extreme youth. In an age when a boy of sixteen leads armies and quells insurrections, a boy of thirteen, trained amid all the exciting circumstances which surrounded James Stewart, might well have made a definite choice and acted with full royal intention, perhaps not strong enough to be carried out by its own impulse, yet giving a real sanction and force to the power which an elder and stronger man was in a position to wield. We have no such means of forming an idea of the character and personality of the second James as we have of his father. No voice of his sounds in immortal accents to commemorate his loves or his sadness. He appears first passively in the hands of conspirators who played him in his childhood one against the other, a poor little royal pawn in the big game which was so bloody and so tortuous. His young memory must have been full of scares and of guileful expedients, each party and individual about him trying to circumvent the other. Never was child brought up among wilder chances. The bewildering horror of his father's death, the sudden melancholy coronation, and all the nobles in their sounding steel kneeling at his baby feet, which would be followed in his experience by no expansion or indulgence, but by the confinement of the castle; the terrible loneliness of an imprisoned child, broken after a while by the sudden appearance of his mother, and that merry but alarming jest of his conveyance in the great chest, half stifled in the folds of her embroideries and cloth of gold. Then another flight, and renewed stately confinement among his old surroundings, monotony broken by sudden excitements and the babble in his ears of uncomprehended politics, from which, however, his mind, sharpened by the royal sense that these mysterious affairs were really his own, would no doubt come to find meaning at a far earlier age than could be possible under other circumstances. And then that terrible scene, most appalling of all, when he had to look on and see the two lads, not so much older than himself, young gallants, so brave and fine, to whom the boy's heart would draw in spite of all he might have heard against them, so much nearer to himself than either governor or chancellor, those two noble Douglases, suddenly changed under his eyes from gay and welcome guests to horrified victims, with all the tragic passion of the betrayed and lost in their young eyes. Such a scene above all must have done much to mature the intelligence of a boy full like all his race of spirit and independence, and compelled to look on at so much which he could not stop or remedy. Thus passive and helpless, yet with the fiction of supremacy in his name, we see the boy only by glimpses through the tumultuous crowd about him with all their struggles for power, until suddenly he flashes forth into the foreground, the chief figure in a scene more violent and terrible still than any that had preceded it, taking up in his own person the perpetual and unending struggle, and striking for himself the decisive blow. There is no act so well known in James's life as that of the second Douglas murder, which gives a sinister repetition, always doubly impressive, to the previous tragedy. And yet between the two what fluctuations of feeling, what changes of policy, how many long exasperations, ineffectual pardons, convictions unwillingly formed, must have been gone through. That he was both just and gentle we have every possible proof, not only from the unanimous consent of the chronicles, but from the manner in which, over and over again, he forgives and condones the oft-repeated offences of his friend. And there could be few more interesting psychological studies than to trace how, from the sentiments of love and admiration he once entertained for Douglas, he was wrought to such indignation and wrath as to yield to the weird fascination of that precedent which must have been so burnt in upon his childish memory, and to repeat the tragedy which within the recollection of all men had marked the Castle of Edinburgh with so unfavourable a stain.

We are still far from that, however, in the bright days when Douglas was Lieutenant-Governor of the kingdom, and the men who had murdered his kinsmen were making what struggle they could against his enmity, which pursued them to the destruction of one family and the frequent hurt and injury of the other. How Livingstone and his household escaped from time to time but were finally brought to ruin, how Crichton wriggled back into favour after every overthrow, sometimes besieged in his castle for months together, sometimes entrusted with the highest and most honourable missions, it would be vain to tell in detail. James would seem to have yielded to the inspiration of his new prime minister for a period of years, until his mind had fully developed, and he became conscious, as his father had been, of the dangers which arose to the common weal from the lawless sway of the great nobles, their continual feuds among themselves, and the reckless independence of each great man's following, whose only care was to please their lord, with little regard either for the King and Parliament or the laws they made. During this period his mother died, though there is little reason to suppose that she had any power or influence in his council, or that her loss was material to him. She had married a second time, another James Stewart called the Black Knight of Lorne, and had taken a considerable part in the political struggles of the time always with a little surrounding of her own, and a natural hope in every change that it might bring her son back to her. It is grievous that with so fair a beginning, in all the glow of poetry and love, this lady should have dropped into the position of a foiled conspirator, undergoing even the indignity of imprisonment at the hands of the Regents whom she sometimes aided and sometimes crossed in their arrangements. But a royal widow fallen from her high estate, a queen-mother whose influence was feared and discouraged and every attempt at interference sternly repressed, would need to have been of a more powerful character than appears in any of her actions to make head against her antagonists. She died in Dunbar in 1446, of grief, it is said, for the death of her husband, who had been banished from the kingdom in consequence of some hasty words against the power of the Douglas, of whom however, even while he was still in disgrace, Sir James Stewart had been a supporter. Thus ended in grief and humiliation the life which first came into sight of the world in the garden of the great donjon at Windsor some quarter of a century before, amid all the splendour of English wealth and greatness, and all the sweet surroundings of an English May.

James was married in 1450, when he had attained his twentieth year, to Mary of Gueldres, about whom during her married life the historians find nothing to say except that the King awarded pardon to various delinquents at the request of the Queen—an entirely appropriate and becoming office. No doubt his marriage, so distinct as a mark of maturity and independence, did something towards emancipating James from the Douglas influence; and it is quite probable that the selection of Sir William Crichton to negotiate the marriage and bring home the bride may indicate a lessening supremacy of favour towards Douglas in the mind of his young sovereign. Pitscottie records a speech made to the Earl and his brothers by the King, when he received and feasted them after their return from a successful passage of arms with the English on the Border, in which James points out the advantage of a settled rule and lawful authority, and impresses upon them the necessity of punishing robbers and reivers among their own followers, and seeing justice done to the poor, as well as distinguishing themselves by feats of war. By this time the Douglases had once more become a most formidable faction. The head of the house had so successfully worked for his family that he was on many occasions surrounded by a band of earls and barons of his own blood, his brothers having in succession, by means of rich marriages or other means of aggrandisement, attained the same rank as himself, and, though not invariably, acting as his lieutenants and supporters, while his faction was indefinitely increased by the followers of these cadets of his house, all of them now important personages in the kingdom. It was perhaps the swelling pride and exaltation of a man who had all Scotland at his command, and felt himself to have reached the very pinnacle of greatness, which suggested the singular expedition to France and Rome upon which Douglas set forth, in the mere wantonness of ostentation and pride, according to the opinion of all the chroniclers, to spread his own fame throughout the world, and show the noble train and bravery of every kind with which a Scottish lord could travel. It was an incautious step for such a man to take, leaving behind him so many enemies; but he would seem to have been too confident in his own power over the King, and in his greatness and good fortune, to fear anything. No sooner was he gone, however, than all the pent-up grievances, the complaints of years during which he had wielded almost supreme power in Scotland, burst forth. The King, left for the first time to himself and to the many directors who were glad to school him upon this subject, was startled out of his youthful ease by the tale of wrong and oppression which was set before him. No doubt Sir William Crichton would not be far from James's ear, nor the representatives of his colleague, whom Douglas had pursued to the death. The state of affairs disclosed was so alarming that John Douglas, Lord Balvenie, the brother of the Earl, who was left his procurator and representative in his absence, was hastily summoned to Court to answer for his chief. Balvenie, very unwilling to risk any inquisition, held back, until he was seized and brought before the King. His explanations were so little satisfactory, that he was ordered at once to put order in the matter, and to "restore to every man his own:" a command which he received respectfully, but as soon as he got free ignored altogether, keeping fast hold of the ill-gotten possessions, and hoping, no doubt, that the momentary indignation would blow over, and all go on as before. James, however, was too much roused to be trifled with. When he saw that no effect was given to his orders he took the matter into his own hands. The Earl of Orkney with a small following was first sent with the King's commission to do justice and redress wrongs: but when James found his ambassador insulted and repulsed, he took the field himself, first making proclamation to all the retainers of the Douglas to yield to authority on pain of being declared rebels. Arrived in Galloway, he rode through the whole district, seizing all the fortified places, the narrow peel-houses of the Border, every nest of robbers that lay in his way, and, according to one account, razed to the ground the Castle of Douglas itself, and placed a garrison of royal troops in that of Lochmaben, the two chief strongholds of the house. But James's mission was not only to destroy but to restore. He divided the lands thus taken from the House of Douglas, according to Pitscottie, "among their creditors and complainers, till they were satisfied of all things taen from them, whereof the misdoers were convict." This, however, must only have applied, one would suppose, to the small losses of the populace, the lifted cows and harried lands of one small proprietor and another. "The King," adds the same authority, "notwithstanding of this rebellion, was not the more cruel in punishing thereof nor he was at the beginning:" while Buchanan tells us that his clemency and moderation were applauded even by his enemies.