Proserpina, Volume 2

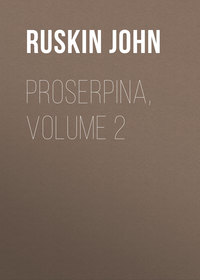

We have therefore, ourselves, finally then, twelve following species to study. I give them now all in their accepted names and proper order,—the reasons for occasional difference between the Latin and English name will be presently given.

25. We will try, presently, what is to be found out of useful, or pretty, concerning all these twelve violets; but must first find out how we are to know which are violets indeed, and which, pansies.

Yesterday, after finishing my list, I went out again to examine Viola Cornuta a little closer, and pulled up a full grip of it by the roots, and put it in water in a wash-hand basin, which it filled like a truss of green hay.

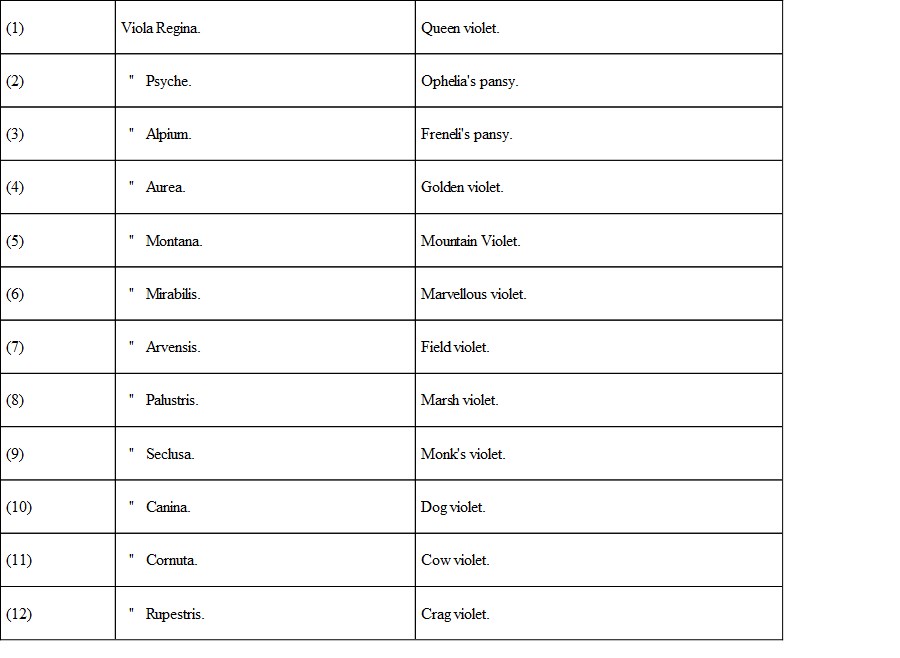

Pulling out two or three separate plants, I find each to consist mainly of a jointed stalk of a kind I have not yet described,—roughly, some two feet long altogether; (accurately, one 1 ft. 10½ in.; another, 1 ft. 10 in.; another, 1 ft. 9 in.—but all these measures taken without straightening, and therefore about an inch short of the truth), and divided into seven or eight lengths by clumsy joints where the mangled leafage is knotted on it; but broken a little out of the way at each joint, like a rheumatic elbow that won't come straight, or bend farther; and—which is the most curious point of all in it—it is thickest in the middle, like a viper, and gets quite thin to the root and thin towards the flower; also the lengths between the joints are longest in the middle: here I give them in inches, from the root upwards, in a stalk taken at random.

But the thickness of the joints and length of terminal flower stalk bring the total to two feet and about an inch over. I dare not pull it straight, or should break it, but it overlaps my two-foot rule considerably, and there are two inches besides of root, which are merely underground stem, very thin and wretched, as the rest of it is merely root above ground, very thick and bloated. (I begin actually to be a little awed at it, as I should be by a green snake—only the snake would be prettier.) The flowers also, I perceive, have not their two horns regularly set in, but the five spiky calyx-ends stick out between the petals—sometimes three, sometimes four, it may be all five up and down—and produce variously fanged or forked effects, feebly ophidian or diabolic. On the whole, a plant entirely mismanaging itself,—reprehensible and awkward, with taints of worse than awkwardness; and clearly, no true 'species,' but only a link.2 And it really is, as you will find presently, a link in two directions; it is half violet, half pansy, a 'cur' among the Dogs, and a thoughtless thing among the thoughtful. And being so, it is also a link between the entire violet tribe and the Runners—pease, strawberries, and the like, whose glory is in their speed; but a violet has no business whatever to run anywhere, being appointed to stay where it was born, in extremely contented (if not secluded) places. "Half-hidden from the eye?"—no; but desiring attention, or extension, or corpulence, or connection with anybody else's family, still less.

FIG. II.

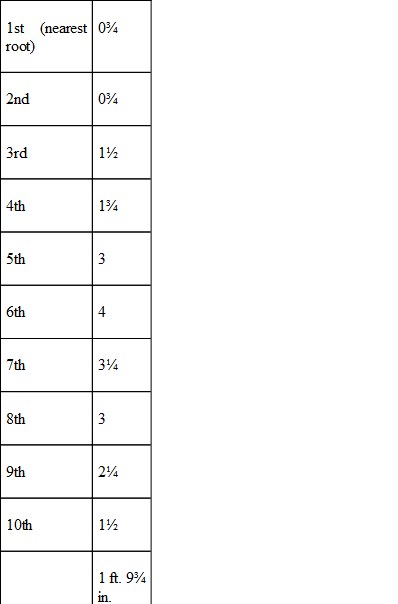

26. And if, at the time you read this, you can run out and gather a true violet, and its leaf, you will find that the flower grows from the very ground, out of a cluster of heart-shaped leaves, becoming here a little rounder, there a little sharper, but on the whole heart-shaped, and that is the proper and essential form of the violet leaf. You will find also that the flower has five petals; and being held down by the bent stalk, two of them bend back and up, as if resisting it; two expand at the sides; and one, the principal, grows downwards, with its attached spur behind. So that the front view of the flower must be some modification of this typical arrangement, Fig. M, (for middle form). Now the statement above quoted from Figuier, § 16, means, if he had been able to express himself, that the two lateral petals in the violet are directed downwards, Fig. II. A, and in the pansy upwards, Fig. II. C. And that, in the main, is true, and to be fixed well and clearly in your mind. But in the real orders, one flower passes into the other through all kinds of intermediate positions of petal, and the plurality of species are of the middle type. Fig. II. B.3

27. Next, if you will gather a real pansy leaf, you will find it—not heart-shape in the least, but sharp oval or spear-shape, with two deep cloven lateral flakes at its springing from the stalk, which, in ordinary aspect, give the plant the haggled and draggled look I have been vilifying it for. These, and such as these, "leaflets at the base of other leaves" (Balfour's Glossary), are called by botanists 'stipules.' I have not allowed the word yet, and am doubtful of allowing it, because it entirely confuses the student's sense of the Latin 'stipula' (see above, vol. i., chap. viii., § 27) doubly and trebly important in its connection with 'stipulor,' not noticed in that paragraph, but readable in your large Johnson; we shall have more to say of it when we come to 'straw' itself.

28. In the meantime, one may think of these things as stipulations for leaves, not fulfilled, or 'stumps' or 'sumphs' of leaves! But I think I can do better for them. We have already got the idea of crested leaves, (see vol. i., plate); now, on each side of a knight's crest, from earliest Etruscan times down to those of the Scalas, the fashion of armour held, among the nations who wished to make themselves terrible in aspect, of putting cut plates or 'bracts' of metal, like dragons' wings, on each side of the crest. I believe the custom never became Norman or English; it is essentially Greek, Etruscan, or Italian,—the Norman and Dane always wearing a practical cone (see the coins of Canute), and the Frank or English knights the severely plain beavered helmet; the Black Prince's at Canterbury, and Henry V.'s at Westminster, are kept hitherto by the great fates for us to see. But the Southern knights constantly wore these lateral dragon's wings; and if I can find their special name, it may perhaps be substituted with advantage for 'stipule'; but I have not wit enough by me just now to invent a term.

29. Whatever we call them, the things themselves are, throughout all the species of violets, developed in the running and weedy varieties, and much subdued in the beautiful ones; and generally the pansies have them, large, with spear-shaped central leaves; and the violets small, with heart-shaped leaves, for more effective decoration of the ground. I now note the characters of each species in their above given order.

30. I. VIOLA REGINA. Queen Violet. Sweet Violet. 'Viola Odorata,' L., Flora Danica, and Sowerby. The latter draws it with golden centre and white base of lower petal; the Flora Danica, all purple. It is sometimes altogether white. It is seen most perfectly for setting off its colour, in group with primrose,—and most luxuriantly, so far as I know, in hollows of the Savoy limestones, associated with the pervenche, which embroiders and illumines them all over. I believe it is the earliest of its race, sometimes called 'Martia,' March violet. In Greece and South Italy even a flower of the winter.

"The Spring is come, the violet's gone,The first-born child of the early sun.With us, she is but a winter's flower;The snow on the hills cannot blast her bower,And she lifts up her dewy eye of blueTo the youngest sky of the selfsame hue.And when the Spring comes, with her hostOf flowers, that flower beloved the mostShrinks from the crowd that may confuseHer heavenly odour, and virgin hues.Pluck the others, but still rememberTheir herald out of dim December,—The morning star of all the flowers,The pledge of daylight's lengthened hours,Nor, midst the roses, e'er forgetThe virgin, virgin violet."43. It is the queen, not only of the violet tribe, but of all low-growing flowers, in sweetness of scent—variously applicable and serviceable in domestic economy:—the scent of the lily of the valley seems less capable of preservation or use.

But, respecting these perpetual beneficences and benignities of the sacred, as opposed to the malignant, herbs, whose poisonous power is for the most part restrained in them, during their life, to their juices or dust, and not allowed sensibly to pollute the air, I should like the scholar to re-read pp. 251, 252 of vol. i., and then to consider with himself what a grotesquely warped and gnarled thing the modern scientific mind is, which fiercely busies itself in venomous chemistries that blast every leaf from the forests ten miles round; and yet cannot tell us, nor even think of telling us, nor does even one of its pupils think of asking it all the while, how a violet throws off her perfume!—far less, whether it might not be more wholesome to 'treat' the air which men are to breathe in masses, by administration of vale-lilies and violets, instead of charcoal and sulphur!

The closing sentence of the first volume just now referred to—p.254—should also be re-read; it was the sum of a chapter I had in hand at that time on the Substances and Essences of Plants—which never got finished;—and in trying to put it into small space, it has become obscure: the terms "logically inexplicable" meaning that no words or process of comparison will define scents, nor do any traceable modes of sequence or relation connect them; each is an independent power, and gives a separate impression to the senses. Above all, there is no logic of pleasure, nor any assignable reason for the difference, between loathsome and delightful scent, which makes the fungus foul and the vervain sacred: but one practical conclusion I (who am in all final ways the most prosaic and practical of human creatures) do very solemnly beg my readers to meditate; namely, that although not recognized by actual offensiveness of scent, there is no space of neglected land which is not in some way modifying the atmosphere of all the world,—it may be, beneficently, as heath and pine,—it may be, malignantly, as Pontine marsh or Brazilian jungle; but, in one way or another, for good and evil constantly, by day and night, the various powers of life and death in the plants of the desert are poured into the air, as vials of continual angels: and that no words, no thoughts can measure, nor imagination follow, the possible change for good which energetic and tender care of the wild herbs of the field and trees of the wood might bring, in time, to the bodily pleasure and mental power of Man.

32. II. VIOLA PSYCHE. Ophelia's Pansy.

The wild heart's-ease of Europe; its proper colour an exquisitely clear purple in the upper petals, gradated into deep blue in the lower ones; the centre, gold. Not larger than a violet, but perfectly formed, and firmly set in all its petals. Able to live in the driest ground; beautiful in the coast sand-hills of Cumberland, following the wild geranium and burnet rose: and distinguished thus by its power of life, in waste and dry places, from the violet, which needs kindly earth and shelter.

Quite one of the most lovely things that Heaven has made, and only degraded and distorted by any human interference; the swollen varieties of it produced by cultivation being all gross in outline and coarse in colour by comparison.

It is badly drawn even in the 'Flora Danica,' No. 623, considered there apparently as a species escaped from gardens; the description of it being as follows:—

"Viola tricolor hortensis repens, flore purpureo et cœruleo, C.B.P., 199." (I don't know what C.B.P. means.) "Passim, juxta villas."

"Viola tricolor, caule triquetro diffuso, foliis oblongis incisis, stipulis pinnatifidis," Linn. Systema Naturæ, 185.

33. "Near the country farms"—does the Danish botanist mean?—the more luxuriant weedy character probably acquired by it only in such neighbourhood; and, I suppose, various confusion and degeneration possible to it beyond other plants when once it leaves its wild home. It is given by Sibthorpe from the Trojan Olympus, with an exquisitely delicate leaf; the flower described as "triste et pallide violaceus," but coloured in his plate full purple; and as he does not say whether he went up Olympus to gather it himself, or only saw it brought down by the assistant whose lovely drawings are yet at Oxford, I take leave to doubt his epithets. That this should be the only Violet described in a 'Flora Græca' extending to ten folio volumes, is a fact in modern scientific history which I must leave the Professor of Botany and the Dean of Christ Church to explain.

34. The English varieties seem often to be yellow in the lower petals, (see Sowerby's plate, 1287 of the old edition), crossed, I imagine, with Viola Aurea, (but see under Viola Rupestris, No. 12); the names, also, varying between tricolor and bicolor—with no note anywhere of the three colours, or two colours, intended!

The old English names are many.—'Love in idleness,'—making Lysander, as Titania, much wandering in mind, and for a time mere 'Kits run the street' (or run the wood?)—"Call me to you" (Gerarde, ch. 299, Sowerby, No. 178), with 'Herb Trinity,' from its three colours, blue, purple, and gold, variously blended in different countries? 'Three faces under a hood' describes the English variety only. Said to be the ancestress of all the florists' pansies, but this I much doubt, the next following species being far nearer the forms most chiefly sought for.

35. III. VIOLA ALPINA. 'Freneli's Pansy'—my own name for it, from Gotthelf's Freneli, in 'Ulric the Farmer'; the entirely pure and noble type of the Bernese maid, wife, and mother.

The pansy of the Wengern Alp in specialty, and of the higher, but still rich, Alpine pastures. Full dark-purple; at least an inch across the expanded petals; I believe, the 'Mater Violarum' of Gerarde; and true black violet of Virgil, remaining in Italian 'Viola Mammola' (Gerarde, ch. 298).

36. IV. VIOLA AUREA. Golden Violet. Biflora usually; but its brilliant yellow is a much more definite characteristic; and needs insisting on, because there is a 'Viola lutea' which is not yellow at all; named so by the garden florists. My Viola aurea is the Rock-violet of the Alps; one of the bravest, brightest, and dearest of little flowers. The following notes upon it, with its summer companions, a little corrected from my diary of 1877, will enough characterize it.

"June 7th.—The cultivated meadows now grow only dandelions—in frightful quantity too; but, for wild ones, primula, bell gentian, golden pansy, and anemone,—Primula farinosa in mass, the pansy pointing and vivifying in a petulant sweet way, and the bell gentian here and there deepening all,—as if indeed the sound of a deep bell among lighter music.

"Counted in order, I find the effectively constant flowers are eight;5 namely,

"1. The golden anemone, with richly cut large leaf; primrose colour, and in masses like primrose, studded through them with bell gentian, and dark purple orchis.

"2. The dark purple orchis, with bell gentian in equal quantity, say six of each in square yard, broken by sparklings of the white orchis and the white grass-flower; the richest piece of colour I ever saw, touched with gold by the geum.

"3 and 4. These will be white orchis and the grass flower.6

"5. Geum—everywhere, in deep, but pure, gold, like pieces of Greek mosaic.

"6. Soldanella, in the lower meadows, delicate, but not here in masses.

"7. Primula Alpina, divine in the rock clefts, and on the ledges changing the grey to purple,—set in the dripping caves with

"8. Viola (pertinax—pert); I want a Latin word for various studies—failures all—to express its saucy little stuck-up way, and exquisitely trim peltate leaf. I never saw such a lovely perspective line as the pure front leaf profile. Impossible also to get the least of the spirit of its lovely dark brown fibre markings. Intensely golden these dark fibres, just browning the petal a little between them."

And again in the defile of Gondo, I find "Viola (saxatilis?) name yet wanted;—in the most delicate studding of its round leaves, like a small fern more than violet, and bright sparkle of small flowers in the dark dripping hollows. Assuredly delights in shade and distilling moisture of rocks."

I found afterwards a much larger yellow pansy on the Yorkshire high limestones; with vigorously black crowfoot marking on the lateral petals.

37. V. VIOLA MONTANA. Mountain Violet.

Flora Danica, 1329. Linnæus, No. 13, "Caulibus erectis, foliis cordato-lanceolatis, floribus serioribus apetalis," i.e., on erect stems, with leaves long heart-shape, and its later flowers without petals—not a word said of its earlier flowers which have got those unimportant appendages! In the plate of the Flora it is a very perfect transitional form between violet and pansy, with beautifully firm and well-curved leaves, but the colour of blossom very pale. "In subalpinis Norvegiæ passim," all that we are told of it, means I suppose, in the lower Alpine pastures of Norway; in the Flora Suecica, p. 306, habitat in Lapponica, juxta Alpes.

38. VI. VIOLA MIRABILIS. Flora Danica, 1045. A small and exquisitely formed flower in the balanced cinquefoil intermediate between violet and pansy, but with large and superbly curved and pointed leaves. It is a mountain violet, but belonging rather to the mountain woods than meadows. "In sylvaticis in Toten, Norvegiæ."

Loudon, 3056, "Broad-leaved: Germany."

Linnæus, Flora Suecica, 789, says that the flowers of it which have perfect corolla and full scent often bear no seed, but that the later 'cauline' blossoms, without petals, are fertile. "Caulini vero apetali fertiles sunt, et seriores. Habitat passim Upsaliæ."

I find this, and a plurality of other species, indicated by Linnæus as having triangular stalks, "caule triquetro," meaning, I suppose, the kind sketched in Figure 1 above.

39. VII. VIOLA ARVENSIS. Field Violet. Flora Danica, 1748. A coarse running weed; nearly like Viola Cornuta, but feebly lilac and yellow in colour. In dry fields, and with corn.

Flora Suecica, 791; under titles of Viola 'tricolor' and 'bicolor arvensis,' and Herba Trinitatis. Habitat ubique in sterilibus arvis: "Planta vix datur in qua evidentius perspicitur generationis opus, quam in hujus cavo apertoque stigmate."

It is quite undeterminable, among present botanical instructors, how far this plant is only a rampant and over-indulged condition of the true pansy (Viola Psyche); but my own scholars are to remember that the true pansy is full purple and blue with golden centre; and that the disorderly field varieties of it, if indeed not scientifically distinguishable, are entirely separate from the wild flower by their scattered form and faded or altered colour. I follow the Flora Danica in giving them as a distinct species.

40. VIII. VIOLA PALUSTRIS. Marsh Violet. Flora Danica, 83. As there drawn, the most finished and delicate in form of all the violet tribe; warm white, streaked with red; and as pure in outline as an oxalis, both in flower and leaf: it is like a violet imitating oxalis and anagallis.

In the Flora Suecica, the petal-markings are said to be black; in 'Viola lactea' a connected species, (Sowerby, 45,) purple. Sowerby's plate of it under the name 'palustris' is pale purple veined with darker; and the spur is said to be 'honey-bearing,' which is the first mention I find of honey in the violet. The habitat given, sandy and turfy heaths. It is said to grow plentifully near Croydon.

Probably, therefore, a violet belonging to the chalk, on which nearly all herbs that grow wild—from the grass to the bluebell—are singularly sweet and pure. I hope some of my botanical scholars will take up this question of the effect of different rocks on vegetation, not so much in bearing different species of plants, as different characters of each species.7

41. IX. VIOLA SECLUSA. Monk's Violet. "Hirta," Flora Danica, 618, "In fruticetis raro." A true wood violet, full but dim in purple. Sowerby, 894, makes it paler. The leaves very pure and severe in the Danish one;—longer in the English. "Clothed on both sides with short, dense, hoary hairs."

Also belongs to chalk or limestone only (Sowerby).

X. VIOLA CANINA. Dog Violet. I have taken it for analysis in my two plates, because its grace of form is too much despised, and we owe much more of the beauty of spring to it, in English mountain ground, than to the Regina.

XI. VIOLA CORNUTA. Cow Violet. Enough described already.

XII. VIOLA RUPESTRIS. Crag Violet. On the high limestone moors of Yorkshire, perhaps only an English form of Viola Aurea, but so much larger, and so different in habit—growing on dry breezy downs, instead of in dripping caves—that I allow it, for the present, separate name and number.8

42. 'For the present,' I say all this work in 'Proserpina' being merely tentative, much to be modified by future students, and therefore quite different from that of 'Deucalion,' which is authoritative as far as it reaches, and will stand out like a quartz dyke, as the sandy speculations of modern gossiping geologists get washed away.

But in the meantime, I must again solemnly warn my girl-readers against all study of floral genesis and digestion. How far flowers invite, or require, flies to interfere in their family affairs—which of them are carnivorous—and what forms of pestilence or infection are most favourable to some vegetable and animal growths,—let them leave the people to settle who like, as Toinette says of the Doctor in the 'Malade Imaginaire'—"y mettre le nez." I observe a paper in the last 'Contemporary Review,' announcing for a discovery patent to all mankind that the colours of flowers were made "to attract insects"!9 They will next hear that the rose was made for the canker, and the body of man for the worm.

43. What the colours of flowers, or of birds, or of precious stones, or of the sea and air, and the blue mountains, and the evening and the morning, and the clouds of Heaven, were given for—they only know who can see them and can feel, and who pray that the sight and the love of them may be prolonged, where cheeks will not fade, nor sunsets die.

44. And now, to close, let me give you some fuller account of the reasons for the naming of the order to which the violet belongs, 'Cytherides.'

You see that the Uranides, are, as far as I could so gather them, of the pure blue of the sky; but the Cytherides of altered blue;—the first, Viola, typically purple; the second, Veronica, pale blue with a peculiar light; the third, Giulietta, deep blue, passing strangely into a subdued green before and after the full life of the flower.

All these three flowers have great strangenesses in them, and weaknesses; the Veronica most wonderful in its connection with the poisonous tribe of the foxgloves; the Giulietta, alone among flowers in the action of the shielding leaves; and the Viola, grotesque and inexplicable in its hidden structure, but the most sacred of all flowers to earthly and daily Love, both in its scent and glow.

Now, therefore, let us look completely for the meaning of the two leading lines,—

"Sweeter than the lids of Juno's eyes,Or Cytherea's breath."45. Since, in my present writings, I hope to bring into one focus the pieces of study fragmentarily given during past life, I may refer my readers to the first chapter of the 'Queen of the Air' for the explanation of the way in which all great myths are founded, partly on physical, partly on moral fact,—so that it is not possible for persons who neither know the aspect of nature, nor the constitution of the human soul, to understand a word of them. Naming the Greek gods, therefore, you have first to think of the physical power they represent. When Horace calls Vulcan 'Avidus,' he thinks of him as the power of Fire; when he speaks of Jupiter's red right hand, he thinks of him as the power of rain with lightning; and when Homer speaks of Juno's dark eyes, you have to remember that she is the softer form of the rain power, and to think of the fringes of the rain-cloud across the light of the horizon. Gradually the idea becomes personal and human in the "Dove's eyes within thy locks,"10

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.