The Evolution of Photography

In the Canadian City I did not find business very lively, so after viewing the fine Cathedral of Notre Dame, the mountain, and other places, I left Montreal and proceeded by rail to Boston. The difference between the two cities was immense. Montreal was dull and sleepy, Boston was all bustle and life, and the people were as unlike as the cities. On my arrival in Boston, I put up at the Quincy Adams Hotel, and spent the first few days in looking about the somewhat quaint and interesting old city, hunting up Franklin Associations, and revolutionary landmarks, Bunker Hill, and other places of interest. Having satisfied my appetite for these things, I began to look about me with an eye to business, and called upon the chief Daguerreans and photographers in Boston. Messrs. Southworth and Hawes possessed the largest Daguerreotype establishment, and did an excellent business. In their “Saloon” I saw the largest and finest revolving stereoscope that was ever exhibited. The pictures were all whole-plate Daguerreotypes, and set vertically on the perpendicular drum on which they revolved. The drum was turned by a handle attached to cog wheels, so that a person sitting before it could see the stereoscopic pictures with the utmost ease. It was an expensive instrument, but it was a splendid advertisement, for it drew crowds to their saloon to see it and to sit, and their enterprise met with its reward.

At Mr. Whipple’s gallery, in Washington Street, a dual photography was carried on, for he made both Daguerreotypes and what he called “crystallotypes,” which were simply plain silver prints obtained from collodion negatives. Mr. Whipple was the first American photographer who saw the great commercial advantages of the collodion process over the Daguerreotype, and he grafted it on the elder branch of photography almost as soon as it was introduced. Indeed, Mr. Whipple’s establishment may be considered the very cradle of American photography as far as collodion negatives and silver prints are concerned, for he was the very first to take hold of it with spirit, and as early as 1853 he was doing a large business in photographs, and teaching the art to others. Although I had taken collodion negatives in England with Mawson’s collodion in 1852, I paid Mr. Whipple fifty dollars to be shown how he made his collodion, silver bath, developer, printing, &c., &c., for which purpose he handed me over to his active and intelligent assistant and newly-made partner, Mr. Black. This gave me the run of the establishment, and I was somewhat surprised to find how vast and varied were his mechanical appliances for reducing labour and expediting work. The successful practice of the Daguerreotype art greatly depended on the cleanness and highly polished surface of the silvered plates, and to secure these necessary conditions, Mr. Whipple had, with characteristic and Yankee-like ingenuity, obtained the assistance of a steam engine which not only “drove” all the circular cleaning and buffing wheels, but an immense circular fan which kept the studio and sitters delightfully cool. Machinery and ingenuity did a great many things in Mr. Whipple’s establishment in the early days of photography. Long before the Ambrotype days, pictures were taken on glass and thrown upon canvas by means of the oxyhydrogen light for the use of artists. At that early period of the history of photography, Messrs. Whipple and Black did an immense “printing and publishing” trade, and their facilities were “something considerable.” Their toning, fixing, and washing baths were almost worthy the name of vats.

Messrs. Masury and Silsby were also early producers of photographs in Boston, and in 1854 employed a very clever operator, Mr. Turner, who obtained beautiful and brilliant negatives by iron development. On the whole, I think Boston was ahead of New York for enterprise and the use of mechanical appliances in connection with photography. I sold my colours to most of the Daguerreotypists, and entered into business relations with two of the dealers, Messrs. French and Cramer, to stock them, and then started for New York to make arrangements for my return to England.

When I returned to New York the season was over, and everyone was supposed to be away at Saratoga Springs, Niagara Falls, Rockaway, and other fashionable resorts; but I found the Daguerreotype galleries all open and doing a considerable stroke of business among the cotton planters and slave holders, who had left the sultry south for the cooler atmosphere of the more northern States. The Daguerreotype process was then in the zenith of its perfection and popularity, and largely patronised by gentlemen from the south, especially for large or double whole-plates, about 16 by 12 inches, for which they paid fifty dollars each. It was only the best houses that made a feature of these large pictures, for it was not many of the Daguerreans that possessed a “mammoth tube and box”—i.e., lens and camera—or the necessary machinery to “get up” such large surfaces, but all employed the best mechanical means for cleaning and polishing their plates, and it was this that enabled the Americans to produce more brilliant pictures than we did. Many people used to say it was the climate, but it was nothing of the kind. The superiority of the American Daguerreotype was entirely due to mechanical appliances. Having completed my business arrangements and left my colours on sale with the principal stock dealers, including the Scovill Manufacturing Company, Messrs. Anthony, and Levi Chapman.

I sailed from New York in October 1854, and arrived in England in due time without any mishap, and visiting London again as soon as I could, I called at Mr. Mayall’s gallery in Regent Street to see Dr. Bushnell, whom I knew in Philadelphia, and who was then operating for Mr. Mayall. While there Mr. Mayall came in from the Guildhall, and announced the result of the famous trial, “Talbot versus Laroche,” a verbatim report of which is given in the Journal of the Photographic Society for December 21st, 1854. Mr. Mayall was quite jubilant, and well he might be, for the verdict for the defendant removed the trammels which Mr. Fox Talbot attempted to impose upon the practice of the collodion process, which was Frederick Scott Archer’s gift to photographers. That was the first time that I had met Mr. Mayall, though I had heard of him and followed him both at Philadelphia and New York, and even at Niagara Falls. At that time Mr. Mayall was relinquishing the Daguerreotype process, though one of the earliest practitioners, for he was in business as a Daguerreotypist in Philadelphia from 1842 to 1846, and I know that he made a Daguerreotype portrait of James Anderson, the tragedian, in Philadelphia, on Sunday, May 18th, 1845. During part of the time that he was in Philadelphia he was in partnership with Marcus Root, and the name of the firm was “Highschool and Root,” and about the end of 1846 Mr. Mayall opened a Daguerreotype studio in the Adelaide Gallery, King William Street, Strand, London, under the name of Professor Highschool, and soon after that he opened a Daguerreotype gallery in his own name in the Strand, which establishment he sold to Mr. Jabez Hughes in 1855. The best Daguerreotypists in London in 1854 were Mr. Beard, King William Street, London Bridge; Messrs. Kilburn, T. R. Williams and Claudet, in Regent Street; and W. H. Kent, in Oxford Street. The latter had just returned from America, and brought all the latest improvements with him. Messrs. Henneman and Malone were in Regent Street doing calotype portraits. Henneman had been a servant to Fox Talbot, and worked his process under favourable conditions. Mr. Lock was also in Regent Street, doing coloured photographs. He offered me a situation at once, if I could colour photographs as well as I could colour Daguerreotypes, but I could not, for the processes were totally different. M. Manson, an old Frenchman, was the chief Daguerreotype colourist in London, and worked for all the principal Daguerreotypists. I met the old gentleman first in 1851, and knew him for many years afterwards. He also made colours for sale. Not meeting with anything to suit me in London, I returned to the North, calling at Birmingham on my way, where I met Mr. Whitlock, the chief Daguerreotypist there, and a Mr. Monson, who professed to make Daguerreotypes and all other types. Paying a visit to Mr. Elisha Mander, the well-known photographic case maker, I learnt that Mr. Jabez Hughes, then in business in Glasgow, was in want of an assistant, a colourist especially. Having met Mr. Hughes in Glasgow in 1852, and knowing what kind of man he was, I wrote to him, and was engaged in a few days. I went to Glasgow in January, 1855, and then commenced business relations and friendship with Mr. Hughes that lasted unbroken until his death in 1884. My chief occupation was to colour the Daguerreotypes taken by Mr. Hughes, and occasionally take sitters, when Mr. Hughes was busy, in another studio. I had not, however, been long in Glasgow, when Mr. Hughes determined to return to London. At first he wished me to accompany him, but it was ultimately arranged that I should purchase the business, and remain in Glasgow, which I did, and took possession in June, Mr. Hughes going to Mr. Mayall’s old place in the Strand, London. Mr. Hughes had been in Glasgow for nearly seven years, and had done a very good business, going first as operator to Mr. Bernard, and succeeding to the business just as I was doing. While Mr. Hughes was in Glasgow he was very popular, not only as a Daguerreotypist, but as a lecturer. He delivered a lecture on photography at the Literary and Philosophical Society, became an active member of the Glasgow Photographic Society, and an enthusiastic member of the St. Mark’s Lodge of Freemasons. Only a day or two before he left Glasgow, he occupied the chair at a meeting of photographers, comprising Daguerreotypists and collodion workers, to consider what means could be adopted to check the downward tendency of prices even in those early days. I was present, and remember seeing a lady Daguerreotypist among the company, and she expressed her opinion quite decidedly. Efforts were made to enter into a compact to maintain good prices, but nothing came of it. Like all such bandings together, the band was quickly and easily broken.

I had the good fortune to retain the best of Mr. Hughes’s customers, and make new ones of my own, as well as many staunch and valuable friends, both among what I may term laymen and brother Masons, while I resided in Glasgow. Most of my sitters were of the professional classes, and the elite of the city, among whom were Sir Archibald Alison, the historian, Col. (now General) Sir Archibald Alison, Dr. Arnott, Professor Ramsey, and many of the princely merchants and manufacturers. Some of my other patrons—for I did all kinds of photographic work—were the late Norman Macbeth, Daniel McNee (afterwards Sir Daniel), and President of the Scottish Academy of Art, and also Her Majesty the Queen, for she bought two of my photographs of Glasgow Cathedral, and a copy of my illustration of Hood’s “Song of the Shirt,” copies of which I possess now, and doubtless so does Her Majesty. One of the most interesting portraits I remember taking while I was in Glasgow was that of John Robertson, who constructed the first marine steam engine. He was associated with Henry Bell, and fitted the “Comet” with her engine. Mr. Napier senr., the celebrated engineer on the Clyde, brought Robertson to sit to me, and ordered a great many copies. I also took a portrait of Harry Clasper, of rowing and boat-building notoriety, which was engraved and published in the Illustrated London News. Several of my portraits were engraved both on wood and steel, and published. At the photographic exhibition in connection with the meeting of the British Association held in Glasgow, in 1855, I saw the largest collodion positive on glass that ever was made to my knowledge. The picture was thirty-six inches long, a view of Gourock, or some such place down the Clyde, taken by Mr. Kibble. The glass was British plate, and cost about £1. I thought it a great evidence of British pluck to attempt such a size. When I saw Mr. Kibble I told him so, and expressed an opinion that I thought it a waste of time, labour, and money not to have made a negative when he was at such work. He took the hint, and at the next photographic exhibition he showed a silver print the same size. Mr. Kibble was an undoubted enthusiast, and kept a donkey to drag his huge camera from place to place. My pictures frequently appeared at the Glasgow exhibition, but at one, which was burnt down, I lost all my Daguerreotype views of Niagara Falls, Whipple’s views of the moon, and many other valuable pictures, portraits, and views, which could never be replaced.

THIRD PERIOD. COLLODION

FREDERICK SCOTT ARCHER.

From Glass Positive by R. Cade, Ipswich. 1855.

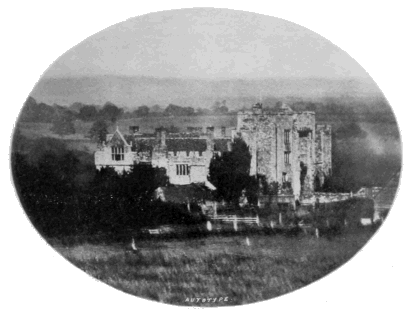

HEVER CASTLE, KENT.

Copy of Glass Positive taken by F. Scott Archer in 1849.

THIRD PERIOD

COLLODION TRIUMPHANT

In 1857 I abandoned the Daguerreotype process entirely, and took to collodion solely; and, strangely enough, that was the year that Frederick Scott Archer, the inventor, died. Like Daguerre, he did not long survive the publication and popularity of his invention, nor did he live long enough to see his process superseded by another. In years, honours, and emoluments, he fell far short of Daguerre, but his process had a much longer existence, was of far more commercial value, benefitting private individuals and public bodies, and creating an industry that expanded rapidly, and gave employment to thousands all over the world; yet he profited little by his invention, and when he died, a widow and three children were left destitute. Fortunately a few influential friends bestirred themselves in their interest, and when the appeal was made to photographers and the public to the Archer Testimonial, the following is what appeared in the pages of Punch, June 13th, 1857:—

“To the Sons of the Sun“The inventor of collodion has died, leaving his invention unpatented, to enrich thousands, and his family unportioned to the battle of life. Now, one expects a photographer to be almost as sensitive as the collodion to which Mr. Scott Archer helped him. A deposit of silver is wanted (gold will do), and certain faces, now in the dark chamber, will light up wonderfully, with an effect never before equalled by photography. A respectable ancient writes that the statue of Fortitude was the only one admitted to the Temple of the Sun. Instead whereof, do you, photographers, set up Gratitude in your little glass temples of the sun, and sacrifice, according to your means, in memory of the benefactor who gave you the deity for a household god. Now, answers must not be negatives.”

The result of that appeal, and the labours of the gentlemen who so generously interested themselves on behalf of the widow and orphans, was highly creditable to photographers, the Photographic Society, Her Majesty’s Ministers, and Her Majesty the Queen. What those labours were, few now can have any conception; but I think the very best way to convey an idea of those labours and their successful results will be to reprint a copy of the final report of the committee.

The Report of the Committee of the Archer Testimonial“The Committee of the Archer Testimonial, considering it necessary to furnish a statement of the course pursued towards the attainment of their object, desire to lay before the subscribers and the public generally a full report of their proceedings.

“Shortly after the death of Mr. F. Scott Archer, a preliminary meeting of a few friends was held, and it was determined that a printed address should be issued to the photographic world.

“Sir William Newton, cordially co-operating in the movement, at once made application to Her Most Gracious Majesty. The Queen, with her usual promptitude and kindness of heart, forwarded a donation of £20 towards the Testimonial. The Photographic Society of London, at the same time, proposed a grant of £50, and this liberality on the part of the Society was followed by an announcement of a list of donations from individual members, which induced your Committee to believe that if an appeal were made to the public, and those practising the photographic art, a sum might be raised sufficiently large, not only to relieve the immediate wants of the widow and children, but to purchase a small annuity, and thus in a slight degree compensate for the heavy loss they had sustained by the premature death of one to whom the photographic art had already become deeply indebted.

“To aid in the accomplishment of this design, Mr. Mayall placed the use of his rooms at the service of a committee then about to be formed. Sir William Newton and Mr. Roger Fenton consented to act as treasurers to the fund, and the Union, and London and Westminster Banks kindly undertook to receive subscriptions.

“Your Committee first met on the 8th day of June, 1857, Mr. Digby Wyatt being called to the chair, when it was resolved to ask the consent of Professors Delamotte and Goodeve to become joint secretaries. These duties were willingly accepted, and subscription lists opened in various localities in furtherance of the Testimonial.

“Your Committee met on the 8th day of July, and again on the 4th day of September, when, on each occasion, receipts were announced and paid into the bankers.

“The Society of Arts having kindly offered, through their Secretary, the use of apartments in the house of the Society for any further meetings, your Committee deemed it expedient to accept the same, and passed a vote of thanks to Mr. Mayall for the accommodation previously afforded by that gentleman.

“Your Committee, believing that the interests of the fund would be better served by a short delay in their proceedings, resolved on deferring their next meeting until the month of November, or until the Photographic Society should resume its meetings, when a full attendance of members might be anticipated; it being apparent that individually and collectively persons in the provinces had withheld their subscriptions until the grant of the Photographic Society of London had been formally sanctioned at a special meeting convened for the purpose, and that their object—the purchase of an annuity for Mrs. Archer and her children—could only be effected by the most active co-operation among all classes.

“Your Committee again met on the 26th of November, when it was resolved to report progress to the general body of subscribers, and that a public meeting be called for the purpose, at which the Lord Chief Baron Pollock should be requested to preside. To this request the Lord Chief Baron most kindly and promptly acceded; and your Committee determined to seek the co-operation of their photographic friends and the public to enable them to carry out in its fullest integrity the immediate object of securing some small acknowledgment for the eminent services rendered to photography by the late Mr. Archer.

“At this meeting it was stated that an impression existed, which to some extent still exists, that Mr. Archer was not the originator of the Collodion Process; your Committee, therefore, think it their duty to state emphatically that they are fully satisfied of the great importance of the services rendered by him, as an original inventor, to the art of photography.

“Professor Hunt, having studied during twenty years the beautiful art of photography in all its details, submitted to the Committee the following explanation of Mr. Archer’s just right:—

“‘As there appears to be some misconception of the real claim of Mr. Archer to be considered as a discoverer, it is thought desirable to state briefly and distinctly what we owe to him. There can be no doubt that much of the uncertainty which has been thought by some persons to surround the introduction of collodion, has arisen from the unobtrusive character of Mr. Archer himself, who deferred for a considerable period the publication of the process of which he was the discoverer.

“‘When Professor Schönbein, of Basle, introduced gun-cotton at the meeting of the British Association at Southampton in 1846, the solubility of this curious substance in ether was alluded to. Within a short time collodion was employed in our hospitals for the purposes of covering with a film impervious to air abraded surfaces on the body; its peculiar electrical condition was also known and exhibited by Mr. Hall, of Dartford, and others.

“‘The beautiful character of the collodion film speedily led to the idea of using it as a medium for receiving photographic agents, and experiments were made by spreading the collodion on paper and on glass, to form with it sensitive tablets. These experiments were all failures, owing to the circumstance that the collodion was regarded merely as a sheet upon which the photographic materials were to be spread; the dry collodion film being in all cases employed.

“‘To Mr. Archer, who spent freely both time and money in experimental research, it first occurred to dissolve in the collodion itself the iodide of potassium. By this means he removed every difficulty, and became the inventor of the collodion process. The pictures thus obtained were exhibited, and some of the details of the process communicated by Mr. Scott Archer in confidence to friends before he published his process. This led, very unfortunately, to experiments by others in the same direction, and hence there have arisen claims in opposition to those of this lamented photographer. Everyone, however, acquainted with the early history of the collodion process freely admits that Mr. Archer was the sole inventor of iodized collodion, and of those manipulatory details which still, with very slight modifications, constitute the collodion process, and he was the first person who published any account of the application of this remarkable accelerating agent, by which the most important movement has been given to the art of photography.’

“Your committee, in May last, heard with deep regret of the sudden death of the widow, Mrs. Archer, which melancholy event caused a postponement of the general meeting resolved upon in November last. Sir Wm. Newton thereupon resolved to make another effort to obtain a pension for the three orphan children, now more destitute than ever, and so earnestly did he urge their claim upon the Minister, Lord Derby, that a reply came the same day from his lordship’s private secretary, saying, ‘The Queen has been pleased to approve of a pension of fifty pounds per annum being paid from the Civil List to the children of the late Mr. Frederick Scott Archer, in consideration of the scientific discoveries of their father,’ his lordship adding his regrets ‘that the means at his disposal have not enabled him to do more in this case.’ Your committee, to mark their sense of the value of the services rendered to the cause by Sir William Newton, thereupon passed a vote of thanks to him. In conclusion, your committee have to state that a trust deed has been prepared, free of charge, by Henry White, Esq., of 7, Southampton Street, which conveys the fund collected to trustees, to be by them invested in the public securities for the sole benefit of the orphan children. The sum in the Union Bank now amounts to £549 11s. 4d., exclusive of interest, and the various sums—in all about £68—paid over to Mrs. Archer last year. Thus far, the result is a subject for congratulation to the subscribers and your committee, whose labours have hitherto not been in vain. Your committee are, nevertheless, of opinion that an appeal to Parliament might be productive of a larger recognition of the claim of these orphan children—a claim not undeserving the recognition of the Legislature, when the inestimable boon bestowed upon the country is duly considered. Since March 1851, when Mr. Archer described his process in the pages of the Chemist, how many thousands must in some way or other have been made acquainted with the immense advantages it offers over all other processes in the arts, and how many instances could be adduced in testimony of its usefulness? For instance, its value to the Government during the last war, in the engineering department, the construction of field works, and in recording observations of historical and scientific interest. Your committee noticed that an attractive feature of the Photographic Society’s last exhibition was a series of drawings and plans, executed by the Royal Engineers, in reduction of various ordnance maps, at a saving estimated at £30,000 to the country. The non-commissioned officers of this corps are now trained in this art, and sent to different foreign stations, so that in a few years there will be a network of photographic stations spread over the world, and having their results recorded in the War Department, and, in a short time, all the world will be brought under the subjugation of art.