Formosa. Country of success

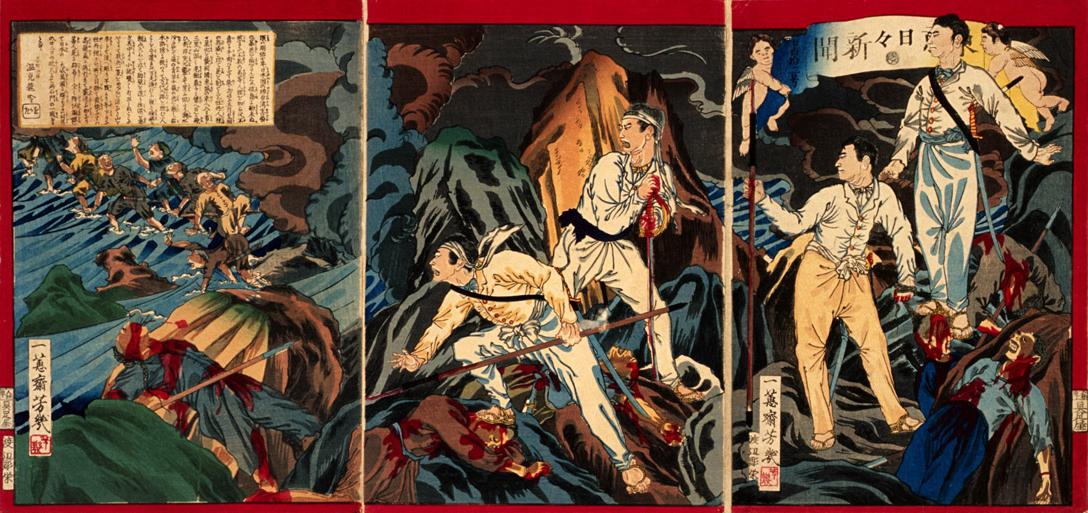

The fishermen were accidentally washed ashore by a wave to the southeastern coast of Taiwan.

The main instigators of the massacre were natives from the Kuarut and Bo-otang tribes.

The 12 surviving crew members were rescued by the Chinese and taken to Taiwan, from where they were handed over to Fujian officials. Later, by agreement, they were sent home.

Ryukyu Archipelago Governor Oyama Tsunayoshi, deputy head of Kagoshima Province, reported to the Japanese central government, calling for revenge. Prudently perhaps, any decision on the issue was postponed.

In 1873, a second similar incident occurred when Taiwanese natives attacked a Japanese ship from the village of Kashiwa, Okayama Prefecture. The ship was wrecked in Taiwanese waters and four crew members were beaten to death.

This event infuriated the Japanese public, which actively demanded the most decisive measures from the authorities. Foreign Minister Soejima Taeomi, sent to the court of Emperor Qing, received an audience with Emperor Tongzhi and appealed to the Chinese side with a demand to compensate for the losses.

Responding, the Qing Dynasty Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated that although Taiwan belongs to China, the Taiwanese aborigines are southern barbarians who do not recognize the Qing emperor's supreme power.

Therefore, the latter is not responsible for their actions.

We should note, that until 1895, that is before the transfer of the island to Japan under the Shimonoseki Treaty, the island was divided into two zones:

– the western plains, where the main population was made up of migrants from mainland China; here also lived the indigenous agricultural population – “plain settlers” (pinbu);

– the eastern mountainous zone, where since the 17th century there were restrictions on Chinese migration (the so-called fenshanming – a decree on the closure of the mountains). There was no Chinese administration there, and the local population (Shenfan or Gaoshan – "highlanders") was ruled by elders.

Meanwhile, in Japan, public discontent was growing fuelled by political crisis, unpopular reforms and the outbreak of the Saga uprising.

Encouraged by the Americans, the Japanese government decided to use the recent incidents as an excuse to relieve social tension within the country and carry out a punitive expedition.

In April 1874, the Imperial Adviser Okumu Shigenobu, was appointed head of the Taiwan appanage office, and Lieutenant General Tsugumichi Saigo was appointed the commander of the troops of this office. In addition to the ground forces, impressive naval forces were also involved, including the armoured corvette Ryujo, built in England not long before these events. But at the last moment, the government halted preparations due to protests from the British and US ambassadors, who said the invasion of Taiwan "would destabilize peace in the Far East."

Despite international pressure, in mid-May 1874, the 3,000-strong contingent of the Imperial Japanese Army under the command of Tsugumichi Saigo unauthorizedly set off to Taiwan. A little later, the Japanese authorities were forced to recognize the legitimacy of the campaign. On 22 May 1874, the Japanese gathered their troops in the Taiwanese port of Sheliao and began punitive action against the Paivan aborigines.

The natives reacted to the Japanese in a quite unfriendly manner, and they gave rise to the opening of hostilities by killing several Japanese soldiers, who carelessly went for a walk away from the camp. The next day, General Saigo sent a detachment of troops into the mountains, which, having destroyed the village and massacred most of the male population of the village, returned to the camp with very few casualties. After that, many tribes laid down their arms and voluntarily surrendered to the Japanese. Just a few mountain villages remained hostile.

The desire to weaken the enemy with a decisive blow prompted Saigo to direct his power against them, as the most powerful and stubborn of all his opponents. On June 13, the Japanese army, divided into three groups, entered the hostile territory from different directions. The Japanese moved without encountering strong resistance. But their situation was not easy. Natural conditions seriously complicated their path: torrential rain, typical for this time of year, flooding of rivers and their rapid flow, lack of roads and unfamiliar area entailed many hardships and difficulties.

And the health of the members of the expedition was adversely affected by constant dampness, intense heat and exhausting work. Many fell ill with fever.

The highlanders avoided open combat, which was unequal for them, while firing at the Japanese with impunity from behind the inaccessible rocks, and disturbing them with unexpected attacks. The combat losses of the Japanese were rather small – only 12 men. But 561 Japanese soldiers died of malaria. The Qing dynasty demanded the immediate withdrawal of Japanese troops from Taiwan.

Terashima, who succeeded Soejima as foreign minister, fearing diplomatic complications, sent Japanese Ambassador Okubo Toshimichi to Nagasaki to suspend the expedition.

In August 1874, Okubo arrived in China, where he began negotiations with Zongliyamen (Foreign Ministry).

The parties were irreconcilable, and these negotiations came to an impasse. Eventually, a compromise was agreed upon with the mediation of the British ambassador to China, Thomas Wade.

China was preoccupied with preparations for war with Yettishar (a Muslim state in Xinjiang that emerged following the Dungan uprising).

On October 31, Japan and Qing concluded a truce, under which Japan had to withdraw its troops from Taiwan, and the Chinese had to pay compensation to injured Japanese sailors and relatives of the victims. It was the first international treaty to recognize Japan's sovereignty over the Ryukyu archipelago. The inhabitants of Ryukyu were now subjects of Japan.

They had to pay approximately 18.7 tons of silver to Japan as an indemnity plus twice as much again to compensate the families of the dead sailors.

In addition to this, they had to pay 75 tons of silver for expenses incurred by the Japanese government for laying roads and erecting buildings on the island.

From that time, the Qing authorities were responsible for policing all cases of sea robbery both on the island and in Chinese waters.

Japan provided Formosa to the Chinese and had to leave the island by December 20, 1874.

One day after the departure of the Japanese expedition, the camp was reduced to ashes, the Chinese burning everything they had bought, considering it to be humiliating to use.

In 1875, Taipei became the capital of northern Taiwan. In 1886 Taiwan was singled out as a separate province of China. The defeat in the war with the Japanese forced the Qing government to cede Taiwan to Japan in 1895.

Under the terms of the Shimonoseki Peace Treaty, Taiwan came under the control of the Japanese administration. Having settled on the island, the Japanese first began to study the local tribes.

They call these tribes "takasago" (as the Japanese read "gaoshan"). The Japanese conduct scientific research and classifications and took control of the island.

Following the outbreak of World War II, some villages were converted into paramilitary camps by the Japanese.

Thus, they prepared the local population for service in the Japanese army. Two raid companies were formed from the Aborigines under the command of Japanese commanders, who took part in the battles in the Pacific Ocean, New Guinea, and the Philippines.

They also took part in raids on the American airfield at Browen. During this raid, a Taiwanese suicide squad named "Kaoru Group" was supposed to blow up American planes. The task was only partially completed.

Generally, these Takasago units were distinguished by their good training and excellent fighting qualities.

Local patriots tried to organize Taiwan, as an independent state, “the Republic of Taiwan ". However, this attempt failed. The new Qing government was defeated in the war with the Japanese and ceded Taiwan to Japan in 1895.

The intention of the Chinese to keep Taiwan for themselves by establishing the independent state " the Republic of Taiwan " was quickly suppressed by the Japanese. Taiwan, aka Formosa, was seized by the Japanese. For some time they were heroically resisted by both the Chinese and the aborigines, but modern firearms did their job. Rumour has it that the Japanese made an action movie on this event. Taiwan fit well with the Japanese concept of accretion by islands.

They tried to do everything to make the locals feel like subjects of the Empire of the Rising Sun. Some even believed in this, for example, Teruo Nakamura, one of those who had been hiding out in the jungle for many years after the war.

When he was discovered and captured, it turned out that nobody knew what to do with him. The Japanese patriot spoke neither Japanese nor Chinese. Eventually, he was granted a Japanese pension but was sent to Taiwan to live out his days.

From 1895 to 1945, there was a special period in the life of Taiwan.

At this time, the island was part of the Japanese Empire and was divided into several prefectures: Taihoku, Shinchiku, Tainan, Takao, Taichu, Hoko, Taito, Tarenko.

Where does the name of Taiwan come from?

As for the name itself of the island of Taiwan, there are 2 versions of the origin of the word. Near the first Dutch settlement of Zealand (now – Anping District, Tainan City) there was a settlement of the Siraiya tribe. In their language, this place was called Tayoan. Later, it became more convenient for the Chinese colonists to call the island in their own way – "Da yuan", which means "Big circleTaioan and Dayuan, as well as some other variants were recorded. Gradually, the name of the most developed area had been transferred to the entire island. And since in the area that the Dutch liked so much, there was a bay, convenient for entry of ships and featuring a sandbank, which protected them from the sea waves in the strait, we can trace the borrowing.

Until the end of the 17th century, the island was still better known as "Formosa" to many Europeans. On western maps, it appears as Formosa and until the first half of the 20th century, it often appears under both names.

In historical documents, the name Formosa is used to define Taiwan until the end of Japanese colonial rule in 1945.

The Austronesian Aborigines of the island are sometimes still called "Formosians". And old sailors always called the island Formosa. They also used this name for the strait that separates the mainland and the island.

Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945)

In 1937, Japan launched a large-scale operation against China and Chiang Kai-shek was appointed Generalissimo of the Republic of China in August of the same year. Stalin and Chiang Kai-shek later signed a mutual non-aggression agreement. The USSR then became the only state that provided the Republic of China with very significant military and financial assistance.

In 1938, the largest battle of the Sino-Japanese War took place near the city of Wuhan in central China. The Chinese army numbering over a million held back the Japanese troops for four months. The mobile and well-armed Japanese army used hundreds of gas attacks and eventually forced the Chinese to leave Wuhan. The Japanese lost over 100,000 soldiers in the battle. The damage was so significant that it stopped their advance inland for years.

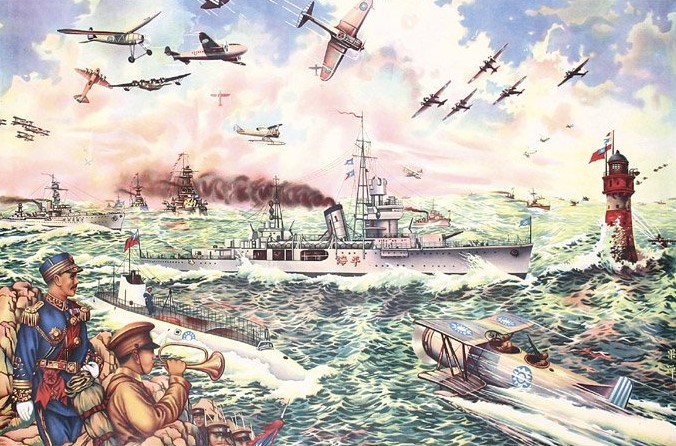

On 23 February 1938, a daring raid of Soviet bombers took place on the Japanese airbase on the island of Taiwan, considered to be outside the zone of action of the enemy air force. On this day, after a 7-hour flight, twenty-eight bombers under the command of pilot Fyodor Polynin bombed the airfield, destroying 40 Japanese aircraft, hangars and a long-term fuel supply. The raid was so unexpected that none of the Japanese fighters even had time to take off. Soviet pilots on the TB-3 bombers were actively fighting against the Japanese invaders. Enraged by the bombing of their airbase in Taiwan, the Japanese decided to take revenge, and on 29 April 1938, just on the birthday of their emperor, attempted to raid the Chinese city of Wuhan.

The raid involved 18 G3M2s bombers protected by 27 Mitsubishi A5Ms fighters, a fierce battle taking place in the sky between Japanese, Soviet and Chinese pilots. Nineteen I-15 and forty-five I-16 Soviet-made fighters shot down ten Japanese bombers and eleven fighters within half an hour, losing twelve of their aircraft.

Within a month of this battle, the Japanese air force stopped flights in the region.

With the support of Soviet military units, the Kuomintang regiments sought to liberate the island from the Japanese. The regiment commander, 27-year-old Ma Chihan, led his troops in the mountains of the southern part of the island. The regiment’s mission was to detain and, if possible, destroy the enemy troops advancing eastward. A Japanese detachment of 2,000 soldiers encircled the men led by Ma Chihan. Ma Chihan positioned his troops up on a hill in an advantageous position and fought off repeated enemy attacks for two days. Then Ma Chihan rallied his troops and overthrew the Japanese in hand-to-hand combat. The Japanese retreated with losses. Tse-yun, at the head of his troops, repulsed the Japanese offensive in the central part of the island. Despite heavy artillery fire, the wounded commander himself led his battalion into a counterattack.

Xin Tse-yun perished, but the offensive was repulsed.The grenade thrower Li Fusheng can deservedly be called the "Hero of the Island's Defence".

This young soldier, a former peasant, became a tank-eliminating specialist. With several grenades suspended on him, he fearlessly rushed towards the Japanese tank and threw a bundle of grenades under its tracks.

During the last Japanese offensive in the southern part of the island, Li Fusheng was wounded six times. The front command awarded the brave grenade thrower and promoted him to Junior Commander.

Machine gunner Wang Pinglu became famous in battles in the central part of the island. Armed with a light machine gun, he crawled up to the enemy battery and killed its crew. The gun battery thus eliminated allowed the liberation troops to launch a swift attack. His heroic deed is still honoured. The feat of another hero fighter, Tszyu Shiyun, was simply amazing. He and his detachment set up an ambush on the enemy, with a task so important, that should his platoon be revealed, it would entail the failure of the entire operation. They

After winning the protracted fifteen-year war with Japan, which claimed the lives of millions of Chinese, Chiang Kai-shek decided not to detain prisoners in China. One million, three hundred thousand Japanese soldiers and officers were repatriated. He also did not take reparations from Japan. But most importantly, he strove to eliminate the reasons that divided the two nations – Chinese and Japanese.

After the communists came to power in 1949, patriotic films about the struggle of the Chinese guerrillas in the Japanese-occupied territories flooded the screens of China. And of course, this struggle was led by the communist revolutionaries.

In reality, the Communist Party had been gradually penetrating the regions where there was no military force and order. Japanese troops were stationed unevenly and only partially controlled the territory they had conquered from the Kuomintang. These areas became ideal environments for the expanding communist movement. The US assisted the government in military matters, though cooperation was complicated by mutual mistrust and disputes between Chiang Kai-shek and the American general Joseph Stilwell. After winning the protracted fifteen-year war with Japan, which claimed the lives of millions of Chinese, Chiang Kai-shek decided not to detain prisoners in China. One million, three hundred thousand Japanese soldiers and officers were repatriated. He also did not take reparations from Japan. But most importantly, he strove to eliminate the reasons that divided the two nations – Chinese and Japanese.

After the communists came to power in 1949, patriotic films about the struggle of the Chinese guerrillas in the Japanese-occupied territories flooded the screens of China. And of course, this struggle was led by the communist revolutionaries.

In reality, the Communist Party had been gradually penetrating the regions where there was no military force and order. Japanese troops were stationed unevenly and only partially controlled the territory they had conquered from the Kuomintang.

These areas became ideal environments for the expanding communist movement.

The US assisted the government in military matters, though cooperation was complicated by mutual mistrust and disputes between Chiang Kai-shek and the American general Joseph Stilwell.

At the beginning of the war, the Communist Party managed to recruit a combat-ready army very rapidly however a Soviet diplomat who visited the base of Chinese communists noted that Chairman Mao did not send his fighters to fight the Japanese.

This is evidenced by the only offensive undertaken by the communists being the Battle of One Hundred Regiments in 1940 led by General Peng Dehuai. Mao criticized Peng for revealing the military strength of the Communist Party. During the "Cultural Revolution" (1966-1976), Peng fell victim to the purge of Mao recalling the General's "betrayal." The issue of the USSR's entry into the war with Japan was significant, and its discussion became the reason for the Soviet side to put forward demands to which the allies were forced to agree. Among them was the expansion of Soviet influence in China and the transfer of the southern part of Sakhalin and all the Kuril Islands. It cannot be ruled out that, by persuading the Soviet Union to start a war with Japan and agreeing to the demands voiced in Yalta by the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, the Allies hoped that the Soviet troops would get bogged down in battles with the Japanese, as the Allied forces. On the other hand, it was calculated that the preparation of the USSR for the beginning of military operations in the Far East would force the Japanese command to stop the transfer of the most combat-ready units from there, which began in 1944 and significantly influenced the course of battles in the Pacific Ocean. Already after the Soviet troops reached the coast of the Yellow Sea, it became clear that the Allied command did not expect such a speed of movement from them.

For example, American ships which were supposed to bring landing troops to the cities of Dalian and Lushun (founded by Russian sailors in the 19th century Dalny and Port Arthur) arrived there after the Soviet landing party had already completely broken the Japanese defences.

The Soviets had their plans for the war with Japan and most importantly, there was an understanding of how to defeat the Kwantung Army with the least losses. First of all, it was necessary to supply the troops of the Trans-Baikal Front with the latest military equipment and weapons, which was achieved by sending part of new tanks, guns and aircraft from the Urals to the east.

Their flow gradually increased as the date for the start of hostilities approached.

When the fighting in Europe ended, a colossal grouping of Soviet troops including 36 rifle, artillery and anti-aircraft artillery divisions, 53 brigades, 5 air divisions, 3 air defence corps and a bomber aviation corps with vast combat experience was then transferred to the Far East in the shortest possible time.

As a result, by August 8, 1945, eleven combined arms, one tank and three air armies were concentrated as part of the Transbaikal and the 1st and 2nd Far Eastern fronts, numbering: 80 rifle divisions, four tank and mechanized corps, six rifle and 40 tank and mechanized brigades.

There were also the Pacific Fleet and the Amur Flotilla. The total number of Soviet troops in the Far East was about 1.6 million people, armed with 26,137 guns and mortars, 5,556 tanks and self-propelled guns, and almost 5,000 aircraft. With an overwhelming advantage in manpower and equipment, the Soviet troops were able to break the resistance of the Kwantung Army in the shortest possible time and in just ten days to reach the designated lines on the shores of the Yellow Sea, completing the defeat of the Japanese.

Formation of the armed forces

Initially, from 1942 to 1943, the Japanese command planned to use only auxiliary supply and transportation units formed from indigenous Taiwanese. However, the changing nature of warfare with the deteriorating situation and the transition from offensive to defence forced the Japanese army command to use these units under the name "Takasago Volunteers" already in 1942.

The initiators of using non-Japanese military personnel were members of military intelligence, whose officers had completed training courses in Nakano. Thanks to their initiative, the concerns of Japanese army officers regarding the ability of native Taiwanese to carry out specialist tasks, were overcome.

Valuable qualities of the jungle inhabitants, particularly their ability to survive in the wild and belligerence, found their application in combat operations behind Allied lines. The practice of bounty hunting and collective hunting, as well as torture and the infliction of intra-vital mutilation on the enemy with cold weapons, re-emerged.

Bounty hunting was a common practice of Taiwanese aborigines in almost all tribes: as part of military rites, to intimidate Chinese settlers, medical magic (heads brought to their native village were supposed to protect residents from diseases and epidemics), as a means of resolving a dispute or as an act of blood feud. Also, the number of heads of killed enemies increased the status of their owners in the tribe and simplified marriage.

The hill tribes believed that the absence of a head prevented the soul from returning to the body or being reborn. The ritual depersonalization of an enemy, dead or alive, with the severance of limbs, castration and blinding, also did not allow the enemy to be reborn and take revenge in a new incarnation. Blood was considered to be the life force of man, the ceremonial shedding of blood on the ground weakened the enemy's soul.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.