Sun at Midnight

SUN AT MIDNIGHT

Rosie Thomas

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2004

Copyright © Rosie Thomas 2004

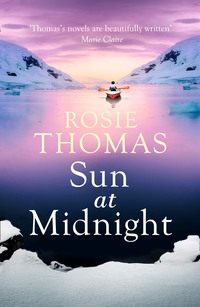

Cover layout design Caroline Young © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2020

Jacket photographs © Singhaphan AIIB/Getty Images (background), Till Findl/Eye Em/Getty Images (kayaker)

Rosie Thomas asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007173525

Ebook Edition © October 2020 ISBN: 9780007389568

Version: 2020-09-25

Praise for Rosie Thomas:

‘Rosie Thomas writes with beautiful, effortless prose, and shows a rare compassion and a real understanding of the nature of love’

The Times

‘Honest and absorbing, Rosie Thomas mixes the bitter and the hopeful with the knowledge that the human heart is far more complicated than any rule suggests’

Mail on Sunday

‘A master storyteller’

Cosmopolitan

‘Thomas’s novels are beautifully written. This one is a treat’

Marie Claire

‘A lush and sweeping voyage of self-discovery’

Eithne Farry, Daily Mail

‘Prepare to be dazzled … an epic tale of sisterhood and betrayal’

Company

‘Heart-rending and beautifully written … I read it in one delicious go, tears pouring down my face. You cannot fail to be moved’

Emma Lee-Potter, Express

‘A terrific book, beautifully written … questions about identity, belonging, infidelity, dying and forgiveness make this a very moving study of the human heart’

Australian Women’s Weekly

Dedication

For the members of the XIth Bulgaria Antarctic Expedition – Christo, Dimo, Dany, Elmira, Koko, Milcho, Murphy, Niki, Roumi, Stanko and Valentin – with love and grateful thanks.

‘always on our team’

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Praise for Rosie Thomas

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Acknowledgements

Keep Reading …

About the Author

Also by Rosie Thomas

About the Publisher

CHAPTER ONE

The wind blew straight off the frozen bay. It was thickened with sleet but the man working on the skeleton roof didn’t seem to notice the cold, or the way the flecks of ice drove into his eyes. He had climbed the raw wood truss at one end of the building and now he straddled the main beam high above the mud- and snow-smeared mess of the site. The hotel had been due to open at the beginning of the short summer season, but the weather had been bad even by local standards, and the work had been slow and dogged with problems. Now the job was way behind schedule. The first fix wasn’t even finished, a month before the completion date. The site crew were mostly Mexican, the main contractor was from Buenos Aires and they all hated the cold. The architect worked for a big commercial practice in Portland, Oregon, and he flew into town and found fault for a couple of days before flying right out again. The hotel company was German-owned, with an aggressive development programme and a policy of cutting construction costs right to the bone.

All of this was routine, however. It was work, life’s usual shit. James Rooker didn’t even bother to think about it.

He vaulted along the beam, squinting against the wind and snow, checking the bolts that secured the plates that held the trusses in place. The wood was split and some of the bolts were missing. This was Juan’s and Pepito’s work, of course.

Down below, the whistle sounded for the end of the day. Instantly a trail of men straggled across the site to deposit their tools and pick up their coats.

Rooker looked across to the bay and the snow slopes lining the Beagle Channel. It was September and the only ship in the harbour was an ugly Russian ice breaker waiting to head south, but in a few more weeks it would be summer and the cruise ships would be moored up on either side of the main jetty. The town would be full of tourists in fleeces and hiking boots, coming and going from their sea voyages and their glacier hikes and waterfall sightseeing trips and treks in the National Park. There would be a little blue-painted funfair train running through the streets, and an employee of the tourist company dressed in a giant penguin suit would spend five hours of every day posing for photographs and using his flipper to shake hands. It would soon be time to be somewhere else. As this occurred to him, Rooker noticed that the snow had stopped. A slice of sky showed through the clouds and an oblique shaft of silver light fell across the sea ice.

He swung down from his beam and clambered down a series of ladders to the ground. The finished hotel would have sympathetic wood cladding, but as yet it was a grey breeze-block slab with holes poked in it for windows. A pair of men had started work today on the ground-floor door and window frames.

He caught sight of Juan in a group making tracks towards the site gate through the skim of wet snow.

‘Hey!’ Rooker yelled. ‘You, Juan, I want you.’

The man stopped and waited. He was small, dark-skinned and hopeless. ‘Sí?’

Rooker towered over him. He jerked a thumb towards the roof timbers. ‘What’s that crap up there?’

The carpenter shrugged. He was used to the foreman’s ways. ‘Weather bad,’ he muttered routinely.

‘Then let’s get the fucking roof on straight, Mex, so we can all have some shelter. Okay?’

‘Sí.’

‘Bad work, no pesos. Comprende?’ Rooker rubbed his thumb and forefinger together.

The man nodded and hitched his canvas bag over his shoulder. It was Wednesday and the crew got paid on Thursdays, so there would be no drinking tonight. Juan just wanted to get back to his lodgings for some food and warmth and a night’s sleep.

‘Get on, then,’ Rooker said, losing patience. Everyone else was already gone, Pepito presumably amongst them. The grey light was fading fast. The roof and its correct fixing would have to wait for tomorrow, yet another day. Juan trudged away and Rooker locked up the metal cabin that served as the site hut and tool store. By the time he was padlocking the gate in the metal fencing it was fully dark. Night fell swiftly at this latitude.

He walked quickly down the hill towards the centre of town. Up here, on the outskirts, the roads that bisected the main streets were still unmade. There were mounds of filthy snow beside the steps up to narrow front doors. The houses were corrugated metal boxes not much more elaborate than the site hut, but they were brightly painted and the curtains were already snugly pulled at most of the windows. A couple of dogs reared and snarled at the end of their chains as he passed. It was bitterly cold now. As he turned right under the dirty orange glare of a street lamp he saw the lights of a plane low in the sky. It was the evening flight from Buenos Aires, coming in to land at the new airport.

The bar he was heading for wasn’t one of the brightly lit ones in the main street parallel to the harbour wall. Those places had check tablecloths and pictures on the walls, and they served fancy-priced beer or coffee or even cocktails to tourists on their way to beef barbecue restaurants. Rooker’s destination was in a side street, down three steps from sidewalk level and behind an unmarked door.

Half a dozen people looked up from their drinks when he came in and a couple of them nodded to him. He stood at the bar and the big barmaid poured him three fingers of whisky without asking what he wanted.

‘Hola,’ she muttered as she slid the tumbler across the bar. She had stopped hoping that Rooker might pay her some attention.

He drank his whisky in silence. There was nothing decorative or homely about the place, only wooden stools and bare floorboards. It was dry and fairly warm and the drink was cheap, and no one who came here was looking for more than that. It was a bar for itinerant workers, fishermen, sailors and foreign kitchen hands, a dingy place in a frontier town at the furthermost end of the world. Or almost the furthermost end.

Rooker was finishing his drink and wondering about another when the fight started. It erupted without warning, for no discernible reason, as fights often did in this place. Suddenly a table was overturned and playing cards fluttered over the floor. Two men growled and wrestled each other like drunken bears. One of them took the other by the throat and shook him, the other crooked his arm and his fist connected with his assailant’s jaw with a sharp crack. They staggered, locked together, and fell over another table. Glasses fell and smashed, and black spatters of drink marked the floor. The other drinkers stood up or shouted and the barmaid wearily reached for the telephone behind the bar.

He sidestepped away from the fracas, his face expressionless. Rooker had seen too many bar fights; this one was monotonously the same as all the others. He reached the door and walked out into the darkness without looking back. He reckoned that he might as well go home, without thinking of the place in this context as home. It was ten minutes away, back up the hill, but in the opposite direction from the new hotel. He moved unhurriedly, his hands in the pockets of his storm coat, not noticing the cold or that it had started snowing again.

The house was a two-storey building, older than most of its neighbours, with protruding eaves and a little loggia at the front. For the few precious weeks of summer there would be flowers in the blue-painted oil drums that stood under wrought-metal lanterns on either side of the front door, but for now there were only crusts of snow, clinging to dead twigs, and a scatter of cigarette butts. Officially Marta didn’t allow smoking in the house.

Rooker let himself in. In the hallway there was a smell of frying meat, an ornate carved-wood coat-stand and about a hundred framed pictures. Marta loved bric-a-brac. He had had to do battle, when he first rented his room, to get her to remove half the stuff that cluttered it up.

As he put his foot on the first stair, Marta stuck her head out of the door that led to her domain at the back of the house.

‘Qué tal, Rook?’

Marta was enormously fat, but she had a lovely face, with smooth pale skin and sad dark eyes. Her husband had left her and she was on the lookout for a replacement. Rooker greeted her without checking his progress up the stairs.

He rented the upper back half of the house. The windows faced straight out on to a steep rocky slope so there wasn’t much light, but in wintertime there wasn’t much light anywhere so this hardly mattered. He didn’t know where he would be when the summer finally did come, but it was unlikely to be here.

He hung up his coat and unlaced his boots. There was an armchair beside a small wood-burning stove, a bookcase, a table and a couple of chairs, and an alcove with a sink and a basic kitchen. In another alcove was a bed and a cupboard. The bathroom was out on the landing and Rooker shared it with the chef from one of the tourist restaurants, who rented the upstairs front.

‘It’s fine,’ he told Marta when she showed the place to him. And it was fine, once he had made her cart away all the religious pictures and lace tablecloths and wool-work cushions that filled it up. He wasn’t fussy about where he lived, so long as it didn’t take up too much of his attention.

He began to make a meal. There was the remainder of a bean and beef casserole that Marta had pressed on him, so he put the pan on an electric ring to heat it up. There was bread, and a block of strong cheese, and some smoked sausage. Rooker was just putting a plate on the table when he heard the unusual sound of someone ringing the downstairs bell. It would be a friend of Guillermo the chef’s, he thought. Guillermo did have the occasional night off work. Or maybe Marta had found a new boyfriend.

There were voices in the hallway, Marta’s and another. The caller was a woman.

Marta came puffing up the stairs and rapped on his door.

‘Rook? You got visitor,’ she called.

He looked around his room, instinctively checking for anything that might give away something of himself. But the place was almost bare, apart from clothes and food, and a few books on the shelves.

‘Rook?’ Marta repeated. Through the thin wood panels of the door he could hear her breathing, but no sound from the other woman, whoever she might be.

He opened the door. Marta’s bulk almost blocked the aperture.

‘Come up, honey,’ she called over her shoulder in her heavily accented American English. His caller wasn’t local, then.

Light, quick footsteps came up the stairs. Marta squeezed herself to one side and he saw that it was Edith.

‘Ede? Christ. What’re you doing here?’

She brought the smell of cold in with her. There was snow on her shoulders and her hair glittered with moisture. She tipped her head and her eyebrows lifted. ‘What kind of a welcome is that?’

‘What kind of arrival is this?’

Edith didn’t let her smile fade. He remembered how white her teeth always looked against her tawny skin. ‘A surprise.’

‘Damn right it is.’

She was carrying a bag. She let it drop now with a thump. Marta looked inquisitively from Rooker to Edith and back again.

Rooker sighed. ‘Okay. Come on in. Gracias, Marta.’

‘De nada.’ She was offended not to be introduced and further included in the unusual event of her back lodger having a visitor.

Edith hoisted her bag, skipped past her and nudged the door shut with her shoulder. She looked around the room, not missing a detail. ‘So this is home? It’s not all that homely, is it?’

‘It’s not home. It’s just where I live.’

After only two minutes Edith knew they had already got off on the wrong footing. Rooker felt her checking herself and trying a different approach.

‘It’s good to see you, Rook.’

She stroked her hair and settled it so it lay back over one shoulder. He took note, as she intended him to do, of how pretty she was and how small and fragile-seeming. Her feet and hands were as tiny as a child’s.

‘What are you doing in Ushuaia?’

She was still smiling at him. Her eyes danced. ‘You know what I’m doing here. And now that I am here, aren’t you going to offer me a drink?’

He was trapped. He looked at the door and at his pan of stew on the electric ring. It was smoking, so he lifted it off. ‘All right, Edith. There’s whisky. Will that do?’

‘Sure.’ She unbuttoned her coat and hung it over the back of a chair, and kicked off her snowboots. She stood in front of the stove, rubbing her hands, then took the tumbler of scotch he handed to her. He poured himself a measure and that was the end of the bottle.

‘Here’s to you and me,’ she said softly and drank. He ignored the toast.

‘How did you get here?’

‘From Buenos Aires, how else? On this evening’s flight.’ The one he had seen coming in to land.

‘Edith, I don’t know why you’re here. I don’t know how you found me…’

‘Frankie told me.’

‘She had no right to do that.’ Frankie was an old friend of Rooker’s. She was younger than he was and although he had known her for fifteen years they had never slept together. He liked that, it made her different. Sometimes he e-mailed her from the locutorio off the main street. Frances was married to a chiropractor she had met at a Jerry Garcia memorial concert, and now lived in New York State with him and their three children. It still surprised Rooker to think of Frances with children, but all the evidence was that she had put her wild days behind her and settled down to being a wife and mother. He liked getting her e-mails about what the kids were up to and the latest funny thing the baby had said. Ross, her husband, was dull but decent.

‘Well, she did.’

He kept his anger in check. Frankie had always liked Edith, out of all Rooker’s girlfriends. And Frankie had his postal address, because she had sent him a book on his birthday. It was The Worst Journey in the World by Apsley Cherry-Garrard. It stood on the shelf behind him now. He had read some of it.

‘Rook?’ Edith breathed. She put her glass on the table and came to him, holding out her hands. When he didn’t take them she grasped the front of his shirt and lifted herself on tiptoe so she could kiss him on the mouth. She tasted of whisky.

‘Don’t do that,’ he ordered. He disentangled himself from her grasp and turned away. The room was too small, there was nowhere to get away from this.

‘I love you,’ Edith said, in a new jagged voice that was raw with accusation.

‘No, you don’t. You’ve just forgotten.’

He hadn’t forgotten. The last time he saw her was in Dallas. He had arrived in Dallas as a pilot for an air charter company but that job had stopped working even before it had started, so he was filling in on yet another building site. Edith had found work as a dancer. They had been living together, an arrangement that only lasted a few weeks this time, and they had gone out drinking one night.

Edith always set out to attract attention, particularly from men in bars, and that night was no exception. She was wearing a tiny skirt that showed her toffee-coloured thighs and a stretchy top that exposed most of her breasts. Before they left the apartment she was shimmying around in front of him, laughing too much and darting hard little glances at him from under her eyelashes. Rooker knew that even if he had loved her, even if he smothered her with enough admiration and affection to suffocate them both, it wouldn’t be enough to satisfy Edith. She was born to be dissatisfied and doomed always to want more than she could get. If she had him, she wanted other men as well, for reassurance. If she didn’t have him she wouldn’t stop wheedling and threatening and seducing until he gave way to her. They had already split up twice before the night in Dallas. But Edith always knew which buttons to press.

That night she had been wild, fuelled by her anger with him and her contempt for the rest of the world. She had barely tasted her first drink before she had her tongue in some guy’s mouth. The man’s hands went straight down inside the little stretchy top and Rooker had hauled him backwards and pinned him against the bar. Even as he did it he was wondering why. He didn’t care who Edith rubbed herself up against. He didn’t want to be here with her, but he couldn’t think of anywhere else that he wanted to be.

‘Don’t do that,’ Rooker had said quietly to Edith’s new friend.

The man tried to smile. ‘Hey, I’m real sorry. I just thought…’ There were beads of sweat in the bristles above his top lip.

Rooker felt as though he was standing beside himself, watching his own actions in boredom and disgust. His hands dropped back to his sides.

‘Come on,’ he said to Edith.

Outside, she moved up against him. She was lithe and taut, like a cat. ‘Hey,’ she breathed in his ear. As always, his aggression excited her.

The evening that had begun badly grew steadily more evil. There were more bars, much more drinking. They found themselves in a place where there was lap dancing and the next thing that happened was that Edith was dancing too, out of her mind and out of her stretchy top and tiny skirt. There was a man whose thick red arms were matted with coarse gingery hair, and Rook saw one of these arms slide between Edith’s thighs. With a weight of sadness on him Rook grabbed her by the back of the neck, just as if she really were a cat, and pushed her out of reach. Then he squared up to the red man, seeing out of the corner of his eye the bar’s security staff heading towards them.

‘Fag,’ the red man sneered.

‘Outside,’ Rook answered.

The night was thick and hot. At first Rook could hardly move against the pressure of ennui and disgust, but when the man’s fist smashed almost casually into the corner of his eye the pain lit a phosphor-white blaze in his head. He hit out, and hit again. The man went down instantly and when Rook looked at him he saw that his face was split wide open. There were teeth and bone in a mess of blood, and Rook was certain that he had killed him. Sick horror and a wash of memories rose up in him and he staggered backwards, hands up in a vain effort to shut out the sight.

He left the man lying on the ground. He left Edith still inside the bar somewhere and he made his way home in painful and blurred slow motion. On the floor of the bathroom were the prints of Edith’s feet outlined in talcum powder. He rubbed them out with the side of his fist as the floor seemed to tilt sideways and the man’s smashed face stared out at him from the mirror on the wall.

When Rooker woke up again he was lying fully dressed on the bed with Edith asleep beside him. He squinted at her, because he could only open one eye. There were black pools of mascara darkening her eye sockets and her breath bubbled through her slack lips. The light in the room was dirty grey and the air was hot to breathe. He sat up very slowly, wincing with pain. There was dried blood on the pillow where his head had rested. Sour-tasting saliva flooded his mouth.

I have to get away from here, from this, he thought.

Before he could move again, Edith stirred. She blinked at him and briefly focused. ‘Dear Jesus,’ she muttered.

Rooker stood up and slowly turned his head to the mirror on her dresser. His left eye was puffed up, the skin crimson and shiny. His eyelashes were crusted black spikes embedded in the bruised tissue. A ragged cut with oozing margins ran from the centre point of his cheekbone to the corner of his eye. The man must have been wearing a heavy ring. He put his fingers up to touch the place, memories of the night before coming back to him in small unwelcome fragments. Edith lay motionless.