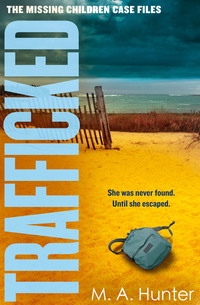

The Missing Children Case Files

I won’t allow my mind to consider how Anna would have coped with such terror. No body has ever been found, and I’m in two minds about which fate I’d rather have come her way. Surviving such abuse feels almost as cruel as having to go through it in the first place; and yet I desperately long for the day when I might be reunited with Anna.

A knock at the door is followed by Jack entering and resting a mug of water on the desk beside the file. There are light brown stains inside the mug where years of tea and coffee have left their mark. I don’t doubt that the water will provide the refreshment my overheated body is craving, but it’s less than appetising.

‘Sorry,’ Jack offers, ‘best I could find. Say, do you fancy getting out of here? Maybe grabbing a drink or a bite to eat somewhere? I know we have the video call with Jemima’s parents in a bit, but how is it going to look if they see us melting in here? There’s a café up the road, and I’m sure we’d both benefit from a breath of fresh air.’

He doesn’t have to ask me twice. Peeling myself off the plastic chair, I grab my satchel and follow him out of the door, before he locks it behind him.

Chapter Three

Now

Uxbridge, London

The fresh air has done wonders to wake my flagging mind, though I really wish we could just stay outside in the glorious sunshine. There is a slight breeze here in Uxbridge, and sitting outside the café has brought back memories of being a carefree student, and skipping lectures with my best friend Rachel so that we could head to the Student Union and spend our student loans on bottled drinks. Hardly appropriate for a writer with a mortgage, but the memory brings a much-needed dose of endorphins.

When we are buzzed back through the police station, even the corridor feels like an oven, and any refreshment the outside breeze had brought is swiftly swallowed up. At least for the duration of the video call with Jemima Hooper’s parents we won’t be trapped in the box room. Instead we’re in a purpose-built suite usually used for reviewing security camera footage during a live investigation. Jack has reserved the room, as it is soundproof and will enable the two of us to perch in front of the laptop’s digital camera.

We have to tread very carefully with Mr and Mrs Hooper, as they don’t know the reason for our call. Their local contact at Northumberland Constabulary has notified them that Jemima’s case notes have been requested by the Metropolitan Police as part of a wider investigation, but they know little more than that. They don’t know that we believe Jemima to be one of the victims in the footage found on Turgood’s hard drive; and I don’t know how they will react to such news.

‘Are you ready?’ Jack asks, straightening the tie he’s just put on to create more of a professional look. I do feel for him; I’m melting in this thin cotton dress, but he must be baking in the wool-blend trousers and buttoned polyester shirt.

I give him a muted nod. The truth is, I’m worried about what conclusions the Hoopers will jump to if they happen to recognise my face. Since the publication of Monsters Under the Bed – the non-fiction book that finally exposed Arthur Turgood, Geoffrey Arnsgill and Timothy MacDonald, as well as catapulting my writing career – I’ve struggled with being recognised by total strangers who assume they know who I am just because they’ve read and empathised with my words; but that isn’t who I am.

I’ve spent the last twenty-seven years of my life trying to find my place in the world, and understand who I am, but I don’t feel any closer to the answer. I wish I could be the confident and sophisticated extrovert my agent Maddie expects me to be. If the Hoopers do recognise me, their first thought is bound to be that I’m planning to write about their daughter’s situation, which couldn’t be further from the truth. At the same time, I don’t want to admit to them that my interest in their daughter is for my own selfish gain.

Jack logs onto the laptop, and fishes in his pocket for his notebook, in which he has scribbled Dave Hooper’s email address. I take the seat furthest from the screen, hoping that their focus remains more on Jack than me. He then sits and types in the address; the computer whirs, and beeps as the call is connected.

‘Good morning, Mr and Mrs Hooper,’ Jack begins, offering a sincere but dispassionate smile. ‘I trust you are both still comfortable with us talking this afternoon?’

‘Aye,’ Dave Hooper replies.

He’s much older than I was anticipating, given Jemima’s relatively young age when she disappeared. The man before us with strawberry blond hair that has all but faded to grey has tired eyes. Even though it’s been years since Jemima’s discovery in Tamworth, it’s clear grief still has a firm hold of him, as it does his wife. She looks a few years younger than her husband, her hair much darker, though it’s possibly dyed, and difficult to tell from the grainy image being projected onto the screen. Despite the obvious pained expression, I instantly see where Jemima inherited her freckles from.

‘Firstly, please accept my condolences on what I’m sure is still a very difficult series of events to process. My name is Police Constable Jack Serrovitz, and I’m the officer who requested access to your daughter’s case file. This is Miss Em—’

‘Have yous found the bastard who killed her at last?’ Dave Hooper interrupts, exhaling a sigh of pent-up frustration.

‘Not exactly, Mr Hooper. Our interest in Jemima’s case isn’t to directly investigate how she died, but to—’

‘So the bastard is still out there then, free to abduct and rape and murder other tots.’

I don’t like to assume that I can understand what they are going through. Every family that experiences a disappearance or an abduction deals with it in different ways, and just because the pain of Anna’s disappearance is still fresh in my mind, I cannot begin to imagine what the Hoopers have been through. But I can see how frustrated Dave Hooper is with the system he feels has failed him in the worst possible way. Not only did the authorities not manage to bring Jemima back, they have also failed to prosecute the person responsible for all their devastating pain.

Jack doesn’t respond to the challenge, instead allowing Dave Hooper to fill the silence with the anger and rebukes he’s kept bottled up. Jack doesn’t flinch once, accepting full responsibility even though he played no part in the failings the Hoopers experienced. Carol Hooper remains silent, but her lips tremble as she grinds her teeth, feeling every word her husband spits.

‘Ah, wha’s the point in any of it, like?’ Dave Hooper exclaims, waving a hand dismissively at the camera, before standing and disappearing off screen.

This certainly wasn’t how either of us had thought the call would go, and we haven’t even broached the topic of what was found on Turgood’s hard drive.

Carol Hooper has remained where she is, and has made no effort to end the call.

‘I am truly sorry for your loss, Mrs Hooper,’ Jack tries again. ‘Please know that nobody here takes your feelings for granted, nor feels anything but the purest sympathy for your loss. I have a young daughter myself, and I cannot even begin to imagine how I would deal with things if anything bad ever happened to her. I truly am sorry.’

She nods for him to continue, but lights a cigarette in the process.

Jack takes a deep breath. ‘There’s no easy way for me to say this, Mrs Hooper. We believe we have found a video of Jemima produced while she was missing. The video is of a sordid nature, and would perhaps account for some of the injuries Jemima sustained prior to her death.’ He takes a deliberate pause to allow the gravity of the statement to sink in.

Carol Hooper’s expression doesn’t change. I had expected shock, anger or for her to lash out at the cruel world, but she remains silent, the only sound coming through the tinny speakers on the laptop that of her inhaling and exhaling the cigarette smoke. For a moment I’m wondering whether she even heard what Jack said, or whether her mind has refused to hear any more negative news about her daughter.

‘Figures,’ she finally says, when Jack isn’t forthcoming.

‘The video is one of several recovered from the hard drive of a suspect in a different case, but we do not believe that that suspect was responsible for the production of the video, or involved in any aspect of Jemima’s abduction or murder.’

‘What d’you wanna know from us, like?’ Carol asks, blowing smoke at the camera.

‘I know you were probably asked lots of different questions at the time Jemima was taken, and I promise you we have reviewed every report linked to the original investigation, but what we are trying to establish is whether Jemima was targeted by the people responsible for the video.’

I desperately wish we’d made the journey to Gateshead to visit the Hoopers in person. Conducting such a sensitive and personal interview by video call feels so intrusive and clinical. I want to reach out and hug Carol Hooper and assure her that we will do whatever we can to bring her daughter’s abusers to justice, but those kinds of platitudes sound so false when delivered via digital means.

‘Yous think she was chosen.’ It’s a statement rather than a question, but the truth is Jack and I have no idea; it’s a theory we’re developing.

‘Can you remember anyone at the time taking a particular interest in Jemima?’ Jack continues. ‘Anyone you can now remember watching you when you’d collect Jemima from school; maybe someone who didn’t look quite right when you took her to the park?’

Carol Hooper shakes her head, stubbing out the cigarette in an ashtray off screen. ‘We went through all that at the time. I didn’t see anything out of the ordinary, like; but we was so busy back then – so stressed out with the business folding – that it was always like we was chasing our tails.’

The Hoopers’ local IT company was in financial straits at the time of Jemima’s abduction, and at one point questions were raised about whether the abduction had been staged for monetary gain. The accusations were levelled during the onslaught of abuse that the Hoopers experienced on social media, but it soon became apparent to the Senior Investigating Officer and his team that the parents weren’t involved.

‘What about clubs and things, Mrs Hooper? Did Jemima attend any after-school activities?’

‘She had swimming lessons at the local pool every Wednesday at five, but that was it, like.’

Swimming pools are notorious for perverts looking to cop an eyeful of barely clothed children, but swimming lessons are generally delivered when pools are closed to the public; at least they are where I’m from. I haven’t seen any mention in the case file of security footage at the swimming pool being viewed to see if anyone matched the description of the person in the baseball cap, but I’d be surprised if that angle wasn’t covered. I make a mental note to speak to Jack about it after the call; at the very least we should follow up with someone on the original investigation team to double-check they considered the possibility.

‘This video with our Jem on it,’ Mrs Hooper begins, lighting a second cigarette, ‘you’re certain it’s her?’

‘Honestly, not one hundred per cent, but there is a strong possibility. We are in the process of trying to identify as many of the victims as we can in order to establish if any kind of pattern exists that might help lead us to those involved. It’s going to take time to piece together, but I do appreciate you making the time to speak to us this morning.’

I don’t know whether it’s Jack’s reference to us, but Carol Hooper is suddenly staring at me. ‘You look really familiar. Did we meet when our Jem was taken?’

I shake my head. ‘My name is Emma Hunter; I’m providing civilian support and oversight to the investigation,’ I say evenly.

Her expression remains blank; either her mind hasn’t made the connection with my name, or the world of celebrity has no place in her life.

‘Have you got kids?’ she asks.

‘No,’ I say with another shake of my head.

‘Aye, yous probably too young yet. Don’t let our misery put you off though. In spite of all that happened, I wouldn’t hesitate to do it all again; I think I’d just make more of an effort to appreciate what we had before it was snatched away.’

I doubt there’s a single person alive who wouldn’t echo that sentiment in some way. None of us realise what we have until it’s gone.

Chapter Four

Then

Poole, Dorset

Waking to the sound of beeping and whirring, she couldn’t believe she’d managed to sleep through such a cacophony until that point. She hadn’t woken to anything but silence for as long as she could remember, and that was the first indication that something wasn’t right. Her entire body ached, as she tried to shuffle her legs in bed, and as her other senses started to sharpen, she suddenly became aware of the strong chemical aroma of cleaning products, but not the fruit-scented varieties she had become accustomed to. These lacked any kind of sweetness.

Her throat felt so dry, and as her memory tried to kick into gear and recall whatever her last action was, she suddenly felt a bubble of bile building in the back of her throat, and before she could prevent it, she knew what was coming. With no time to push the sheets back and race to the toilet, she leaned as far out of the bed as she could and retched; only with nothing in her stomach, it was dry and painful.

‘Whoa, whoa, whoa,’ a voice said from somewhere in the darkness, and was followed by a pair of cool, smooth hands supporting her arms.

Her shoulders tensed with the contact and, fearing a backhanded strike, she promptly finished retching and shuffled back into her pillow, her throat raw from the exertion.

‘There, there,’ the voice said again, but the tones were softer than she was expecting. It wasn’t him.

Her eyelids felt as though they were glued shut, and she had to strain to get them to part even slightly, and when she did, the explosion of light forced her to clamp them shut again. Why was it so bright in her room? And who was this woman with soft hands and kind words?

Finally, her short-term memory engaged, and was suddenly filled with recollections of her finding the door unlocked, and making a break for it through the dark forest, until she found that road, and eventually, just when she’d thought she couldn’t go any further, she’d stumbled into the hospital, and collapsed into a janitor’s arms.

That had to be where she was now: hospital. And that would, therefore, make this woman a nurse of some kind.

The woman’s voice spoke again, but the unfamiliar words flowed too quickly for her to interpret what they meant, so she remained silent, and tried to open her eyes for a second time. Lifting her right hand, she tried to shield her eyes from the light, but as the arm came out from beneath the sheet, it felt heavy, as if weighed down.

‘Easy, easy,’ the nurse’s voice came again, as she took control of the right arm, and rested it back on the bed.

She tried to lift her left arm instead, but something pulled at it, as she did.

‘Easy, easy,’ the nurse said again, followed by the words, ‘hospital… broken… doctor.’

It was no good, she would have to open her eyes, and so bowing her head slightly she focused all of her energy on opening just her left eye, blinking several times to allow it to adjust to the large white light coming from somewhere to the right side of whatever room she was in.

Her vision blurred and focused as fluid filled and cleaned her eye, and there was a slight crackle as her sleep-covered eyelashes fluttered open and closed. She was in some kind of private, very white room. She was lying in a bed, with a metal frame around the sides, and as her eye fell on her right arm, where the nurse’s gloved hands held it in place, she realised it was the thick plaster-cast bandage that had been weighing it down. A flash of her falling to the ground as the car had sped towards her filled her mind.

Focusing her attention on her left arm, she saw a thin plastic tube poking out of the crook in her arm, behind her elbow. The tube led off the bed to a metallic stand and into a blue box, which was whirring and occasionally beeping with bright LED numbers.

Finally, she looked into the face of the nurse; such a pretty and angelic face that for a moment she questioned whether she’d actually died in that janitor’s arms, and this was some form of purgatory she’d been thrown into until she could justify her life to St Peter. Not much hope of being able to justify anything, she silently chastised herself.

The nurse tilted her head, and said something else, ending with, ‘…feeling?’

She tried to say she was thirsty, but the words wouldn’t make it past the burning in her throat, and so she pointed at her neck, and mimed drinking from a glass.

The nurse nodded, and moved around to the other side of the bed, reaching for a transparent plastic jug on the stand just behind it, and proceeded to fill a beaker of water, before dropping a paper straw into it. The nurse held it out for her to drink from, but it was difficult to swallow the lukewarm liquid.

‘Sip,’ the nurse instructed, but it was lost on her.

She eventually spat out the straw, and waved for the nurse to return the beaker to the stand. Looking back at the tube in her arm, she tried to determine what cool and clear liquid was being pumped into her arm, but as she tried to move it closer to her eyes, the nurse prevented her from doing so, shaking her head, and saying something else she couldn’t understand.

The woman in the bed pointed at the large square window off to the right and then at her eyes, grateful when the nurse seemed to pick up on the subtlety of the mime, moving across to the window and drawing the blinds, casting a shadow where the brilliant light had once been. With the room suitably dim, the woman prised her right eye open, the dried goop crackling as it broke apart.

The room was larger than the space she was used to sleeping in. Back at home, the inflatable mattress she slept on was built into a narrow coffin-like recess in the wall, and she felt overwhelmed by all the space around her now. Her room beneath the ground had comprised little more than the bed and a distance of twenty heel-to-toe steps by fifteen heel-to-toe steps. She could no longer recall the sheer panic she’d felt the first day he’d forced her into the room; in fact she could remember little of any life prior to the hole. The occasional shard of memory would penetrate – usually while she slept: images of wide, open beaches; of the sea; of a long boat crossing the sea; of a mother’s hand holding hers. Yet whenever she tried to recall anything about her parents, her mind’s eye would lose focus, and the memory would fracture into a thousand shards.

The nurse was speaking again, but the woman didn’t even attempt to decipher what was being instructed or asked. It was clear she must have broken her arm or wrist, and that was why the plaster cast had been fitted around her right arm; but she had no idea why there was a tube in her arm.

Holding out her hand, the woman cut off the nurse mid-sentence and lifted her left hand, flattening it palm up against the sheet over her legs, before using the fingers of her right hand to mime a pen, and the action of writing. The nurse reached into a pocket at the front of her tabard, pulled out a small notebook and biro, and passed them over. The woman dropped the notebook to the bed, and tried to hold the pen in her right hand, but the plaster between her thumb and index finger made gripping the pen impossible.

The nurse proffered a hand, but the woman shook her head, instead picking up the pen with her left hand and attempting to write, but the letters were jumbled in her mind, and she quickly tore up her first attempt, opting to draw what she wanted to say. The pen was unwieldy, and slipped from her grasp several times, but she finally finished, and handed the notebook back.

The nurse’s eyes widened as they focused on the picture, and she hurried from the room, returning with a tall, thin bespectacled man in a white coat.

‘Bonjour,’ he said, the words echoing in her mind.

She tried to return the greeting, but her throat was still too scratchy.

‘Comment vous-appellez vous?’ the man asked.

Her name? Why was that important? Hadn’t the nurse shown him the drawing? Didn’t he realise why she needed to speak with him?

The man in the white coat continued to consider her, exchanging silent glances with the nurse.

Pressing a hand to his chest, he spoke again. ‘Je m’appelle Monsieur Truffaut. Je suis médecin.’

So, he was a doctor; that made sense given his white coat and presence in the hospital. His eyes were still waiting for her to answer his initial question, and she tried to speak, but her throat was so hoarse. She coughed before raising the four fingers of her left hand.

He frowned as he studied the gesture. ‘Quatre? Four? No, what is your name?’

She extended her hand further, gently waggling the four fingers. ‘Four,’ she croaked.

‘Four what?’ the nurse tried.

‘Four,’ she croaked again.

‘Wait, your name is Four?’ the doctor tried. ‘Vous appelez vous Quatre? Four?’

The woman nodded.

That was what he had called her for as long as she could remember; whenever he wanted something, he would call her ‘Four’; whenever he was angry he would shout ‘Four’; whenever he was sorry, he’d whimper ‘Four’. Why were they struggling to understand?

‘Your name is Four?’ the nurse asked.

She nodded.

Another silent exchange between nurse and doctor, followed by mumbled words that they needn’t have spoken so quietly, as Four could not have understood anyway.

‘Ou habitez-vous, Four? Where do you live?’

Another pointless question! Even if she’d wanted to tell him where he’d kept her, she had no way of providing an address, and her memory of last night’s trawl through the forest and along the road was quickly fading into the recesses of her mind. She had to have been walking for at least an hour but that was merely an estimate. It could have been less than an hour, but certainly felt far longer.

They weren’t getting the message. Four pointed at the notepad that was still being clutched by the anxious-looking nurse.

‘This?’ the nurse asked, passing the pad back.

Four snatched the pad, and gesticulated at the picture of the monster she’d drawn. It was a crude sketch of a large figure chasing a stick version of herself, but surely they could see what she was trying to tell them?

‘Man,’ she croaked. ‘Bad man… coming.’

Chapter Five

Now

Ealing, London

‘Did you see her face when you mentioned the video?’ I ask Jack when the call is over, and he’s driving me back to Rachel’s flat in Ealing where I’m currently sleeping on her sofa bed.

‘She didn’t look surprised,’ he comments, pulling out at the roundabout.

‘I know, right? I swear there was no change in her expression at all. Not shock, not anger, not even denial. Just acceptance. Can you imagine what they must have been through to reach such a place devoid of emotion?’

‘It’s every parent’s worst nightmare,’ Jack concludes. ‘I meant what I said to Carol Hooper on the phone: I don’t know what I’d do if anything ever happened to Mila. I never expected I could ever feel so strongly about another human being, but I swear I would literally lay down my life for that girl.’

I try to meet his gaze, but he’s too focused on the road ahead. Traffic from Uxbridge to the entrance of the A40 is nose-to-tail, as mums and dads and nannies battle through rush-hour traffic to collect and return children to the safety of their homes; most probably oblivious to the pain the likes of Carol and Dave Hooper are going through every second of every day. There’s no school pick-up for them; not any more. I bet they never thought they’d see the day when they would miss this daily circus. So many take it all for granted.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.