The Element Encyclopedia of Secret Signs and Symbols

CHESS

Chess originated in India. The checkerboard that chess is played on is, in itself, a secret symbol. It is symbolic of the world that we understand, that is composed of opposing forces. Also, the black and white colors of the symmetrically arranged squares stand for male/female, light/dark, positive/negative, good/evil in much the same way as the yin-yang sign does. It is no accident that the floor of the Freemason temple has the same construction as the chessboard, a constant reminder of both the harmony and tension between opposites. The pieces, too, are black and white, reinforcing this idea.

The chessboard has a further mystery that can be revealed in the number of the squares. Each side has eight squares. Eight is the number of infinity and of completion, and eight times eight makes 64, the number of cosmic unity. This is the magical number that, in sacred geometry, is the basis of temple construction.

The square shape of the board symbolizes the stability of the Earth and its four corners, the directions and the elements.

Superficially, chess might seem to be a relatively straightforward game, a simple series of different moves ascribed to each of the pieces. However, its complexities are only really revealed when the player is so familiar with the rules that he or she can carry them out automatically. Chess is plainly connected to war strategy and the ability to surprise the opponent. A good player will understand the need to sacrifice pieces in order to gain a greater advantage. Although the pawn may appear to be valueless, it is arguably one of the most important pieces on the board, and certainly the most prolific. We even use the word “pawn” to describe a person that we think is insignificant.

In Ingmar Bergman’s film The Seventh Seal, the knight, Antonius Block, invites the hooded figure of Death to join him in a game, despite the fact that Death warns him that he cannot win. Effectively, chess owes as much to chance as choice, and further underlines the dilemma between the concepts of fate versus free will. The knight knows that he will die, yet he persists in playing the game. Stanley Kubrick, too, believed that his skill as a chess player gave him the discipline to think rationally and to see the bigger picture, an invaluable skill for a film director. The detachment and lack of emotion required by the talented player is synonymous, for many, with an idealized, Zen approach to life.

For the Celts, the game of chess was called “intelligence of the wood.” It was the game of kings and the stakes were high. The game therefore symbolizes the intellect of the king, despite the fact that the most versatile piece on the board is the queen.

CHI ROH

See Labarum.

CHNOUBIS

The Chnoubis is a hybrid creature, with the head of a lion and the tail of a serpent. It was carved onto

stones for use as an amulet, providing protection against poisons in particular. Amulets featuring the Chnoubis date back to the first century and it is supposed that this odd-looking creature may be related to Abraxas, whose image was used in a similar way.

CHOKU REI

A symbol of Reiki healers, the Choku Rei is comprised of a spiral that culminates in a hooked stick. It looks a little like the treble clef used in musical notation. The symbol is used by Reiki healers to increase the power available to them, and to help focus this energy. The meaning of Choku Rei is “place the power of the Universe here.” Healers draw the sign mentally in the air as a form of meditation, generally before and after giving a treatment.

CICATRIX

A cicatrix is a scar, but not just any scar. It refers to a very specific incision that is scored onto the body and carries secret symbols pertaining to the person’s religious or magical beliefs. A very painful process called scarification leaves these raised marks on the skin. Until the end of the nineteenth century, Maori men had ritual scarring all over their faces in order that they might look more frightening to the enemy. A cicatrix acts as a permanent amulet that is an inherent part of the person. Its purpose is similar to that of the tattoo; the pain involved in the process is an important rite of passage. Ritual scarring is popular among dark-skinned people because a tattoo is not particularly visible against the skin.

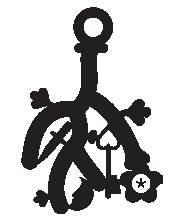

CIMARUTA

In Italian, this means the “sprig of rue.” It is an amulet, made of silver in honor of female energy in the form of the Goddess, comprising a

model of a sprig of rue with various charms in its three branches. The Cimaruta is a very old charm, which evolved from an Etruscan magical amulet. It dates back as far as 4500 BC, although there are more contemporary versions such as the stylized one illustrated here. The charms featured generally include a crescent Moon, a key, stars, daggers, and flowers; different regions of Italy produced their own specific symbols. Also known as the Witch Charm, the Cimaruta is favored by witches, and to see one in someone’s home might indicate the spiritual persuasion of the owner. It is worn either as a pendant or might be hung over a doorway, a possible reason for the Cimaruta being double-sided. When used in this way as an ornament the Cimaruta is usually quite large in size.

The three silver branches of the Cimaruta relate to the notion of the Triple Goddess. The charm itself takes on all the significance of the rue plant as being both protective and a tool of witches, used to cast spells and throw hexes.

CIRCLE

See First signs: Circle.

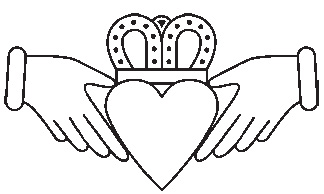

CLADDAGH

The Claddagh is a popular symbol, often incorporated into the design of rings, and worn by people as an attractive piece of ornamentation although they may not know what it symbolizes.

Traditionally used as a wedding ring, the Claddagh is so-called because it was originally made in a Galway fishing village of the same name in seventeenth-century Ireland. However, the elements of the design are much older, stretching back into pre-Christian Celtic history. The Romans had a popular ring design, the Fede, which featured clasped hands. “Fede” means “fidelity.”

CLOTHING

Of all the animal kingdom, man is unique in that he wears clothes. In the Bible, Adam and Eve don fig leaves to cover the newly discovered sexual parts that are a reminder of the lower animal nature. Once we had managed to protect our modesty and keep ourselves warm, our attention turned to the use of clothes as an outward sign of status or of certain religious observances. As secret symbols, clothes have an elaborate history, especially when they are connected to religious beliefs; sacred texts from all religions are full of instructions as to the nature of certain clothes and how they should be worn. This section doesn’t claim to be an extensive analysis of these ideas, but serves merely to point out the meanings of some of the most common items of apparel.

CAPE

The cape has a simple design. At its most basic, it is a piece of cloth with a hole in the middle. Often worn by members of the clergy, when it is called a “chasuble,” the cape shares the same symbolism as the arc or dome that it represents; the vault of the Heavens. This suggests the idea of ascendance. The wearer of the cape becomes a living representation of the Axis Mundi.

CLOAK

As well as being a symbol of religious asceticism, the cloak is the garment of kings. In addition, the word “cloak” has become synonymous with the notion of hiding something; the invisibility cloak is a very ancient idea. The God, Lugh, had such a cloak that enabled him to pass unnoticed through the entire Irish army in order to rescue his son. Effectively, though, the cloak makes the wearer invisible without any need for magical intervention. A cloak, especially a hooded one, is a mask for the body, covering the wearer from head to foot. A cloak can help someone change his or her identity while at the same time confirming it. In the Bible, St. Martin gives half his cloak to the beggar. This is not only a material gesture but also a symbol of his charitable nature.

The Khirka, a specific type of cloak, originally meant a scrap of torn material. However, its unworldly nature made it an appropriate garment for the Sufi mystic.

It was originally blue, signifying a vow of poverty, in the same way that brown and gray have the same meaning to Christian believers. The Sufi receives the Khirka after three years of training, a sign that he is worthy of initiation. To wear the Khirka, the Sufi must understand the three levels of the mystic life. These are the Truth, the Law, and the Path.

FOOTWEAR

When you put your foot upon the ground, this gesture is synonymous with taking possession of the Earth beneath it.

Because the holy ground at churches and temples is not, effectively, a territory that belongs to man, the jumble of shoes, sandals, and boots outside the doors of holy places all over the world may certainly be a sign of respect. However, the owners may not be aware that they are, literally, following in the footsteps of a more ancient idea, that they have no claim to this sacred territory. The footwear is significant because it is removed.

The Children of Israel sealed agreements between two parties by swapping one sandal each. In addition, in Northern China the word for “slipper” and “mutual agreement” is the same. This is why slippers are given as wedding presents.

Shoes also symbolize travel, a meaning that precedes the time of motorized transport. In certain Northern European territories, children leave their shoes out for Father Christmas to fill with gifts; not only is Santa himself making an arduous journey, but his gifts help in the “journey” of the coming year.

Shoes are also a status symbol. Slaves generally went barefoot; hence, the wearing of shoes was the sign of the free man.

The slipper that Cinderella lost, that later proved her identity to the Prince, is an example of the shoe as a sexual symbol. In common interpretations of this tale these “slippers” sound uncomfortable, since they are apparently made of glass. However, it was an old European tradition that a potential suitor would show his sincerity by making his intended bride a pair of fur boots. It is likely that the word for fur, vair, was confused with the word for glass, verre. The sexual symbolism continues with these kinky boots; the old word for fur shares its roots with a word meaning “sheath.”

BELT/GIRDLE

Often the very first piece of clothing to be worn, especially in Asian countries, the girdle or belt is circular, and so it represents the union of spirit and matter, and of eternity. It also symbolizes the binding aspect; the girdle is a synonym for the soul that is bound to the body. Although the girdle is tied around the waist of a baby at birth in some countries, it appears in various other forms. The belts of the martial arts exponent range through the color spectrum from white to black to signify levels of expertise.

The girdle also protects; it acts as a symbolic “wall” through which evil entities cannot penetrate. It’s a sort of spiritual utility belt. The girdle, too, represents the idea of chastity. The belt worn around robes of monks and others who are called to a spiritual life carries the greater significance of the girdle. Notably, in the Middle Ages prostitutes were allowed to wear neither belt nor veil.

To talk of “girding the loins” means to prepare oneself, whether for a journey or something else. The ankh is called the Girdle of Isis or the Buckle of Isis, and carries the same notions of the circle and the knot as binding forces.

A sash is also a kind of girdle, used in Freemasonry, for example, as a symbol of office. The knot itself is often used as a reminder, and the knot in the girdle or belt is a reminder of the promise made when the girdle was donned.

Another form of a girdle is the Sacred Thread, or Poonal (in Tamil) that is worn by male Hindus, particularly those from the Brahmin caste. The Sacred Thread ceremony can happen any time after the boy’s seventh birthday. The thread is handwoven from three sets of three strands, although extra strands are added to represent marriage and children. It measures about 96 times the breadth of a man’s four fingers; this is roughly the same as his height. Resting on the left shoulder, the thread is wrapped around the body, ending under the right arm. It is knotted only once. Once the Sacred Thread ceremony has been carried out, the thread is never taken off although it is replaced once a year. The single knot represents the concept of Brahman, the unity of all things. The numbers of strands in the thread signify various tenets of the Hindu faith.

GLOVE

Freemasons sometimes wear white gloves, not only as a symbol of work to be done, but also to show purity of thought. White gloves are worn for the same reasons in the Catholic Church. They are given to bishops and kings after their investiture, and here they are a reminder of newborn purity. Gloves—especially the highly ornamented kind—are a relatively luxurious item of clothing, emblems of the nobility who used gauntlets as part of the equipment associated with falconry. Gloves on heraldic shields usually indicate some connection with hunting birds.

To “throw down the gauntlet” is still used as a synonym for a challenge, dating back to the days of chivalry, where it was a politer version of a slap but hardly any less shocking.

HEADGEAR

Headgear immediately identifies the status of the owner. The crown, for example, is an immediate recognition of royalty. People in authority wear peaked hats. The beggar goes “cap in hand.” Additionally, headgear itself indicates a relationship with the divine, since the top of the head is effectively the first point of contact with the spirit that descends from above. The symbolic nature of headgear is altogether different from its practical usage. In temples, churches, and other holy places, the feet might be bare but the head is covered as a sign of modesty.

THE CROWN

The open crown, coronet, tiara, or diadem has no practical secular purpose; indeed, the heavier crowns that belong to the sovereignty can be headachingly heavy. The crown is a circle, symbolizing the idea of immortality and eternity, but with the added dimension of a connection between the spiritual and material that is cemented by the ritual of coronation itself, which signifies a blessing, benediction, or union with the divine power that comes from above. Crowns traditionally feature jeweled “rays” signifying Sun beams, an allusion to illumination in all senses of the word.

For the Ancient Egyptians, only pharaohs and deities were permitted to wear the crown. The double crowns of the Pharaohs consisted of the white conical miter that represented Upper Egypt, surrounded by the red encasement of Lower Egypt. The serpent symbol called the Uraeus, again worn only by pharaohs, was incorporated into this sacred crown.

The pope wears a triple crown, or Triregnum (see Papal symbols). The three parts symbolize different aspects of the Catholic faith and of the papal role.

The crown is not always made of princely materials. The crown of laurels is still given as a sign of victory, and for Romans, the highest accolade for a soldier was to be given a crown made of lowly grass. The Corona Graminea signified the ownership of the territory, the right to the land on which the victory had taken place.

The feathered headdresses of Native Americans not only signify the status of the wearer, but the feathers themselves signify the different qualities of the birds they belong to. The most valued of all is the eagle feather. These headdresses epitomize the crown as a Sun symbol.

THE HAT

Which single factor is shared by the old-fashioned policeman’s helmet from the UK, medieval Jewish hats, the papal Triregnum, and the traditional witch’s hat? They all have a tall, conical shape. This has the effect of making the wearer taller than anyone else, more noticeable, and therefore more authoritative. This kind of hat is also a phallic symbol. In addition, the hat of the witch or wizard contains the essence of her magical power in the form of a spiral of energy.

SKULLCAP

Orthodox Jews wear the skullcap (also known as yarmulke or kippah) at all times; it is stated in the Torah that no man should walk more than four paces without the head being covered. This is because of the belief that the head should always be covered in the presence of God, and since God is omnipotent, then it makes sense that the yarmulke is worn at all times.

The yarmulke is not only a recognizable symbol of the faith, but covering the head is in itself a sign of respect for, and fear of, God. Many men also cover their heads for the same reasons.

Covering the head as a sign of respect for God is not restricted to the Jewish faith, although many people tend to restrict this practice to the times that they are actually in the place of worship.

HOOD

The wearing of a hood is sometimes viewed with suspicion, because it masks the face of the wearer. Therefore, the hood is a symbol of invisibility, of disguise, of secrecy, and tends to have negative connotations because we assume that the wearer has reason to conceal him- or herself. The figure of Death, with its scythe, often wears a hood, alluding to the fact that no one knows what form death will take.

HELMET

Like the hood, the helmet is a symbol of invisibility. It also denotes power and invulnerability. The Greek King of Hell, Hades, wears a helmet, and epitomizes all these powers. The covered-face helmet shares many of the same qualities as the mask.

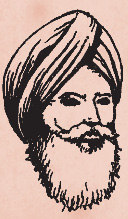

KHALSAS

The five Khalsas are the dress rituals of adherents to the Sikh faith, and signs by which they can be recognized. The five Khalsas are:

1 Kesa—this is uncut hair. The hair remains uncut as a reminder that harm must not be inflicted upon the body. Male Sikhs wear the turban as an article of faith, and it also makes a practical garment to cover and contain the hair.

2 Kacha—this is a particular kind of undergarment as a symbol of marital chastity. Men and women wear similar garments.

3 Kanga—a wooden comb, symbolizing tidiness and cleanliness.

4 Kara—a steel bangle, which serves as a reminder of the truth and of God.

5 Kirpan—a dagger, for ceremonial use only, and a reminder to protect those who need it.

The Khalsas are sometimes referred to as the Five Ks.

ROBES

Nuns, monks, and priests of all persuasions wear the plain robes called “habits”. As well as acting as a kind of uniform, the habit also symbolizes the rejection of material values in favor of spiritual virtues. Generally colored gray or brown, the wearer no longer has to worry about a choice of clothes since external appearances do not matter. Effectively, the habit removes the individual personality. The sackcloth robes worn by ascetics are an extreme statement of the renunciation of worldly appearance, often worn as a penance.

Robes in general signify the rank of the wearer, and because they are distinctly different from everyday dress, they tend to be the preferred dress of spiritual or religious people. In China, the Imperial Robes were very ornate and carried specific symbolism as a part of their design. The round collar was the Heaven, the square hem, the Earth; the wearer of this robe was therefore an intermediary between the two. Latter-day druids of some orders wear green robes to signify the bardic grade, blue for the ovate grade, and the fully initiated druid wears white robes. Indeed, pilgrims of all faiths, including Buddhist, Muslim, and Shinto, wear white robes. Buddhist monks and followers of Hare Krishna wear robes of the sacred saffron color.

The robes of a shaman, like those of the wizard, are covered in magical signs. They are also decorated with feathers (symbolic of transcendence) and the pelt of the animal whose spirit they wish to connect with.

SHIRT

A shirt is a symbol of protection. To “lose one’s shirt” means to relinquish the last vestige of dignity as well as material wealth. However, to give “the shirt off your back” is a gesture of great generosity, indicating a willingness to give away the last of your material possessions. The “hair shirt” is an uncomfortable garment worn by penitents who want to self-inflict punishment.

The tunic is an earlier form of the shirt. The Cathars used it as an analogy for the human body. When they said that fallen angels wore tunics, they meant that they were made of flesh.

VEIL

The veil symbolizes a distinct separation between two states of being, physical objects, or concepts. However, the object effecting this separation is apparently flimsy. It must be remembered that this is a two-way separation; the nun that “takes the veil” to become a Bride of Christ separates herself from the world, but also removes the worldly from her relationship with the spiritual.

The Greek word for veil is “hymen.” The veil that is lifted to reveal the face of the bride at her wedding not only symbolizes her new status, but also alludes to the tearing of the hymen which is the physical outcome of a marriage. The word “revelation” comes from the Latin revelatio, to draw back the veil.

Penetrating a veil, therefore, is symbolic of initiation; hidden knowledge is often described as “veiled.” This veil protects us too; in the same way that the light from the Sun can illuminate, it can also dazzle or even blind us if it comes too close.

The Qu’ran says that women should be addressed from behind a veil. The hijab is the physical manifestation of this idea. Although the hijab has been interpreted by some as a sign of oppression, devout followers of Islam would argue that not only is the wearing of this veil instructed by the Prophet, but also gives the woman a great level of freedom. Here, a veil of misunderstanding separates two ideas and cultures.

According to Buddhists, Maya is the symbolic veil that separates pure reality from the illusory nature of the world in which we live.

COLOR

Despite the fact that colors have an essential part to play in symbolism and the understanding of it, they are, nevertheless, frequently overlooked. Colors are proven to have a profound effect on the human psyche and on our moods. They resonate with the elements, the directions, the seasons, the planets, and astrological signs, as well as holding huge significance in their own right, for example, in the Tarot. Colors, and particular shades of them, confer an immediate identity and make a strong statement. For example, in the green, purple, and white of the Suffragettes (green for hope, purple for dignity, and white for purity), or in the red and white stripes of the old-fashioned barber’s pole (where the white represented the color of flesh and the red was the blood sometimes drawn by the cut-throat razor).