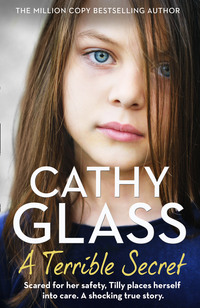

A Terrible Secret

‘I know it’s difficult, love, but it will get easier. I promise.’

‘Mum’s upset and it’s my fault. Perhaps I should just go home like she says.’

‘Do you really think that’s the right decision?’ I asked. ‘It didn’t work out last time.’

‘But I feel sorry for Mum. Who’s going to protect her now?’

‘Tilly, I know you love your mother, but it’s not your job to protect her from your stepfather. She is an adult. Isa will advise her where help is available for victims of domestic abuse.’

‘Is that what she is?’

‘It sounds like it to me.’ I paused. ‘Why does Dave pay for your mobile phone when your mother hasn’t even got one?’ I asked. It was bothering me.

‘He says she doesn’t need one. She doesn’t go out to work so she can use the landline.’

‘What about a computer? Does she have access to email, social media and so on?’

‘No. She doesn’t use the Internet. I don’t think she knows how to.’

‘Does she have friends she keeps in contact with?’

‘Not as far as I know. She doesn’t really go out alone; he’s always with her.’ Which was classic for a victim being coercively controlled by their abuser.

‘Do you have other relatives?’ I asked.

‘Only my gran.’

‘That’s your mother’s mother?’

‘Yes. Mum and I talk to her on the phone sometimes, but I haven’t seen her in ages.’

‘Why?’ I could almost guess the answer.

‘Dave doesn’t get on with her. He says she’s manipulative. Mum doesn’t drive and relies on him to take her, and he doesn’t.’

No surprise there, I thought, although the only one who was likely to be manipulative was Dave, isolating Heather further by keeping her from her mother. I’d been a volunteer in a refuge some years before and knew the signs of coercive control.

‘Try not to worry,’ I told Tilly. ‘Have you got something you can do while I start some dinner?’ It was 4.30 and Lucy, Adrian and Paula would be home later.

‘I’ll phone my friends – they keep texting to find out how I am – unless you want some help?’

‘No, that’s fine. Thank you, but you call your friends. I’ll be in the kitchen if you need me. I was going to make spaghetti bolognaise. Do you eat meat?’

‘Yes, although –’ she stopped.

‘What’s the matter? I can soon make you something else.’

‘No, it’s not that.’ A small, reflective smile crossed her face. It was the first time I had seen any sign of a smile since she’d arrived. ‘I was going to say Dave doesn’t like it, but I don’t have to worry about that any more.’

‘No, you don’t, love.’

‘He gets very angry if Mum makes him something he doesn’t like to eat.’

‘Have you told your social worker things like this?’

‘Some, but not all – not about the food.’

‘Mention it next time you talk to her. Call your friends now.’

I would make a note of this and any other disclosures Tilly made about her home life in my log and update her social worker. It might seem a small point now, but it could form part of a bigger picture. All foster carers in the UK are required to keep a daily record of the child or young person they are looking after. This includes appointments, the child’s health and wellbeing, education, significant events and any disclosures. As well as charting the child’s progress, it can act as an aide-mémoire and also be used as evidence in court. When the child leaves this record is placed on file at the social services.

I left Tilly in the living room about to call her friends while I went into the kitchen. Before I began cooking, I messaged my family’s WhatsApp group to let Paula, Lucy and Adrian know Tilly had arrived, so they didn’t just walk in and find her here. Then I set about making the bolognaise sauce for later.

As I worked, I could hear the rise and fall of Tilly’s voice through the open door of the living room as she talked to her friends. She said pretty much the same thing to all of them, recounting the horror of another fight between her mother and Dave, the police arriving, her mother refusing to press charges and defending Dave, being taken to the social services’ offices and then coming to me. One friend must have asked about me, for I heard her say, ‘Yes, she seems OK, and the house is nice. But I worry about Mum.’

I hoped Tilly would find the strength to stay with me for the time being at least, for if she returned home I felt the situation was likely to deteriorate, and there was no guarantee the social services would apply for a court order to remove her. Their resources are stretched to the limit, and with over 70,000 children in care, and more coming in each day, a baby or young child whose life was in danger would probably have priority over a fourteen-year-old who had removed herself from care.

I heard the front door open and Paula return home. I left what I was doing to go into the hall to greet her. ‘So you had some success at the sales then,’ I said, pleased. She was carrying a number of store bags.

‘I’ve spent a fortune!’ she sighed.

I knew she wouldn’t have done. Paula was careful with her money and only bought what she needed after much deliberation. I knew whatever she’d purchased would be a good buy. We went into the living room and I introduced her to Tilly. Tilly finished on the phone and the two girls said a shy hello. It would be some time before we all relaxed around each other.

‘I’m going to get a drink,’ Paula said to Tilly. ‘Would you like one?’

‘Yes, please. I’ll come with you.’ She stood.

I left the two girls to go to the kitchen and I heard cupboard doors opening and closing as Paula showed Tilly where the juice and squashes were and told her to help herself. I’ve found before that the child or young person we foster often bonds with one of my children before they do with me. Presently both girls appeared carrying a glass of juice. ‘I’m going to my room,’ Paula told me.

‘Is it OK if I go to my room?’ Tilly asked.

‘Yes, of course, love. You do as you wish, make yourself at home.’

‘Thank you.’ She followed Paula upstairs and I heard them talking on the landing for a few moments and then go into their own rooms.

Ten minutes later Lucy arrived home, earlier than usual because the staff at the nursery were working shorter shifts in the week between Christmas and the New Year, as they didn’t have many children in. Most companies had closed for the whole week, but the nursery was open with reduced hours.

‘How are you?’ I asked Lucy, as I did every time I saw her. It was a question laden with hidden meaning now, given her condition.

‘OK. I feel fine.’

‘Good.’ She looked it. She hadn’t had any morning sickness so far; indeed, she seemed to be blossoming. ‘I’m going to get a drink of water,’ she said. I followed her into the kitchen.

‘How’s Darren?’ I asked as she ran a glass of water.

‘He wasn’t in work today. There were only three of us, as there are so few children in this week.’

‘But you spoke to him?’

‘He texted. We’re fine, Mum, don’t worry. Where’s Tilly?’

‘In her room.’

‘How is she?’

‘Finding it a bit difficult at present. I’m sure a few words from you would help.’

‘I’ll talk to her.’

‘Thank you, love, I’d appreciate that.’

Lucy went upstairs. Having been a foster child herself, she knew what it felt like to arrive in a stranger’s home and could usually say something to help. I tried not to think of the new life growing within her while she made the difficult decision of whether to go ahead with the pregnancy or not. Abortion is a highly contentious and emotional subject, but for me it has to be the couple’s right to choose. If Lucy decided to have the baby then I would start to think of it as her unborn child. If she didn’t then it would remain a foetus, not a viable life, harsh though that may sound. I love children and have dedicated my life to looking after them, but unwanted pregnancies ruin lives, and an unwanted child faces the ultimate rejection. Until there is a 100-per-cent effective means of contraception, safe and affordable to all, and available to men and women, then I believe termination has to be kept as an option. Also, it would be inhumane and barbaric to force a woman who’d been raped to go through an unwanted pregnancy and to give birth if they didn’t want to. That’s how I feel, at least, although I appreciate others feel differently.

Adrian returned home just before six o’clock and I introduced him to Tilly. I cooked the spaghetti and called everyone to dinner. We’d just sat down when the doorbell rang.

‘I’ll go,’ I said.

Leaving everyone eating, I went to answer the front door. It was Isa, with four large bin liners stuffed full. ‘There’s more in my car,’ she said.

‘Really? I didn’t think Tilly had asked for that much.’

‘She didn’t. Her stepfather was there and had packed the lot. He’s a nasty piece of work, and angry she’s gone.’

‘He sounds very controlling,’ I said, lowering my voice. ‘Tilly has been telling me things.’

‘Yes, she’s told me a few things too. Where is she now?’

‘Having some dinner.’

‘Leave her to eat until we’ve finished unloading, then I’ll have a chat with her. She’s better off away from him. Her mother was in tears, but don’t tell Tilly that.’

I took my coat from the hall stand, then went out into the cold dark night to Isa’s car. We began unloading the bin liners and stacking them in the hall and front room. Her car was full. Once we’d finished, I counted thirteen in all, each one filled to bursting. I guessed this was most, if not all, of Tilly’s belongings. Her stepfather was giving her a clear message: You’re gone for good. There is no coming back. You’re not welcome here any more.

As I shut the front door Tilly came into the hall and stared at all the bags. ‘Are they all mine?’ she asked, clearly shocked.

‘Yes,’ Isa said. ‘I need to have a chat with you. Is there somewhere private we can go?’

‘In the living room,’ I said. ‘Where you were this afternoon.’

‘Thank you.’

Tilly and Isa went down the hall into the living room and Isa closed the door behind them. As a foster carer you have to accept that sometimes you are excluded from meetings in your own home. Isa had a right to talk to Tilly in private and she should tell me what I needed to know when they’d finished.

I returned to the kitchen-diner where Adrian, Lucy and Paula had finished eating but were still at the table talking.

‘What’s the matter?’ Lucy asked, worried, aware that Isa hadn’t simply dropped off Tilly’s belongings and the two of them were now in the living room.

‘Her stepfather is being quite nasty,’ I said. ‘Isa’s having a chat with Tilly.’

‘Tilly hates him,’ Lucy said vehemently.

‘Did she tell you that?’ Paula asked.

‘Yes, and she’s angry with her mother for putting up with him and choosing him over her.’

‘I know,’ I said. ‘He’s sent most of her belongings. It’s all in the hall and front room. Could someone help me take the bags upstairs? We’ll stack them along the landing so Tilly and I can sort them out slowly in her own time.’

‘Sure,’ Adrian said, and they all stood ready to help.

‘Not you, Lucy, you’re excused,’ I said.

‘Mum, I have to lift toddlers at work who are heavier than a bag of clothes.’

‘Have you pulled a muscle?’ Adrian innocently asked.

‘No, I’m fine,’ Lucy said, while Paula looked at me questioningly.

I avoided her gaze. I hated having secrets in our family – I encourage openness and discussion – but I respected Lucy’s wish not to say anything at present, difficult though it was.

Chapter Three

A Call for Help

Adrian, Paula and Lucy helped me carry all the bin liners containing Tilly’s belongings upstairs and stack them along one side of the landing out of the way, then they went into their rooms for some me time. I returned downstairs to the front room where I took my fostering folder from the drawer. While Tilly was with her social worker and I had the chance, I would read the essential information contained in the placement forms Isa had given to me earlier.

I sat in a chair in the front room and flipped through the half-dozen printed pages. As well as the child’s full name, address and date of birth, it gave a few details of the parents. I saw that Tilly’s mother was forty-nine and her stepfather fifty-two. Tilly was Heather’s only child, but Dave had two other children – Tilly’s stepbrother and stepsister, although she didn’t see them. Neither did she see her natural father, and there were no details about him. Her ethnicity was given as British and her first language English. The box on the form for religion showed none, and her legal status showed she was in care voluntarily under a Section 20, which I knew. She had no special dietary requirements or known allergies. In the section on challenging behaviour it stated that Tilly could become angry sometimes. The name and address of her school came next, and the box for special educational needs was empty. The box for contact arrangements stated that Tilly could visit her mother at home by prior arrangement. I heard the door to the living room open and, setting aside the folder, I went into the hall. It was nearly seven o’clock.

‘Tilly wants to visit her mother tomorrow,’ Isa said. Tilly was standing just behind her social worker. ‘I’ve told her I think she should meet her away from the family home for the time being, in case her stepfather returns.’ This was slightly different from the contact information on the placement form and I assumed it was because of what had happened today. ‘Tilly is concerned that her mother won’t be able to leave the house to meet her because Dave won’t let her,’ Isa continued. ‘But I’ll speak to Heather tomorrow and see what can be arranged.’

‘So we’ll wait until you’ve spoken to her mother before Tilly sees her?’ I clarified.

‘Yes, please. I’ll call you tomorrow.’ And saying goodbye to us both, she left.

I turned to Tilly, who was looking anxious and overwhelmed. I wasn’t surprised, given everything that had happened in the last twenty-four hours. Best keep her occupied, I thought.

‘Your bags are upstairs,’ I said. ‘Let’s start unpacking and sort out what you need for tonight.’

Tilly gave a small nod and, still looking lost and bewildered, came with me upstairs. When she saw the long row of dustbin liners full of her belongings snaking its way around the landing she began to cry. ‘I hate him! I don’t feel like I’ve got a home any more.’ I thought that Dave’s actions had had the desired result and Tilly had got his message.

‘This is your home now,’ I said, putting my arm around her.

‘He’s such a bastard,’ she said, weeping as I held her. ‘I don’t know why Mum stays with him.’

‘I know.’ I soothed and comforted her as best I could.

Lucy’s bedroom door opened and she came out. ‘What’s the matter?’ she asked Tilly, very concerned.

Tilly straightened and rubbed her hand over her eyes.

‘I’ll fetch some tissues,’ I said, and went to the bathroom.

As I did, I heard Lucy tell Tilly: ‘Your stepfather is a creep, but at least you won’t have to do your own packing. I used to hate packing when I moved. I found it really upsetting.’

Lucy rarely talked about those times now, of when she had to move from one home to another – it was all so long ago – but clearly some memories remained. I passed Tilly the box of tissues and she wiped her eyes. Lucy’s phone sounded from her room. ‘Got to get that,’ she said. ‘I’ll catch up with you guys later. It will get better,’ she told Tilly.

‘Yes, thanks,’ Tilly replied, and looked a bit brighter.

A few words from Lucy acknowledging she knew how Tilly felt had helped.

‘I’ve no idea what each bag contains,’ I said to Tilly. ‘We’ll have to open them so you can decide what you need.’ I went to the bathroom for the scissors, at the same time returning the tissues. I then snipped through the tape binding the top of each bag and Tilly began looking in them.

‘This one,’ she said, after a few moments. ‘It’s got my night things and underwear.’ She heaved the bag into her bedroom and came out again. ‘I’ll need the one with my laptop.’

‘That shouldn’t be too difficult to find,’ I said. A few moments later I’d identified the bag containing the laptop and dragged it into Tilly’s room. She took out the laptop and set it on the small table, which acted as a desk.

As she began to unpack I saw that all her belongings had just been stuffed in, not folded or rolled, as though they had been grabbed in anger and shoved in. There was rubbish in the bags too, like sweet wrappers and empty cartons of juice, which you’d normally throw away when packing, not include. It was disrespectful of Dave and I wondered where Tilly’s mother had been and what she’d said – if anything – when he’d been throwing all her daughter’s belongings into these bin liners.

‘I think he just tipped in the whole drawer,’ Tilly said in dismay, and I agreed.

Halfway down the third bag was an open box of sanitary towels. ‘I hate the thought of his hands on my personal things,’ she said, disgusted.

‘I know. Did you have any privacy at home?’ I asked as we worked.

‘Some. I could lock the bathroom door. He wasn’t supposed to go in my bedroom, although I think he did when I wasn’t there.’

‘What makes you say that?’

‘He wears a strong deodorant and I could smell it sometimes when I went in. I told Mum, but she stuck up for him as usual and said I must be mistaken.’

‘Here we all respect each other’s privacy,’ I said, thinking it was a good time to explain a household rule. ‘We don’t go into each other’s bedrooms. This is your space. If any of us wants you, me included, we will knock on your door and wait until you call “come in”. I expect you to do the same to all of us.’

‘Yes, of course.’

I helped Tilly unpack another two bin bags and at the bottom of one was a heap of ornaments. Like everything else, they had just been thrown in and some were chipped and broken. ‘These were my gran’s,’ she said, and looked close to tears again. ‘She gave them to me the last time I saw her.’ At that point I loathed Dave for what he had done, unprofessional though that might have been.

We carefully took out the broken pieces and set them on the table. ‘I should be able to glue some of these,’ I said optimistically.

There was also a framed photograph, which thankfully hadn’t been broken. ‘That’s my gran,’ Tilly said.

I admired the photo of a white-haired lady sitting in a garden on a summer’s day. ‘Would you like to see your gran again if possible?’

‘More than anything in the world,’ Tilly said.

‘I’ll speak to Isa and see what can be arranged, although I’m not promising anything.’

‘Thank you, Cathy. You are kind.’ I could have wept.

Having unpacked four bags, Tilly had what she needed for tonight and tomorrow and said she was going to do some work on her laptop. I carefully gathered up the ornaments and took them downstairs where I glued them back together as best I could and left them to set overnight. I then went into the living room and wrote up my log notes. At nine o’clock Tilly came down and said she was going to have a shower and an early night and could she have a glass of water. I poured it for her, checked she had everything she needed and told her to call me in the night if she was upset. I knew from experience that the first few nights could be very difficult for a looked-after child, regardless of how old they were – alone in a strange room. Tilly promised she’d call if she needed me and, thanking me again, went upstairs.

Later I heard the shower running and then her cross the landing and return to her bedroom. It went quiet and I assumed she was asleep. However, when I went up to check if she was all right I heard her talking on her phone, so I didn’t disturb her.

She was still on the phone when I went up to bed. I got ready, hoping she’d wind up the call before long, but half an hour later, at 10.45, when Lucy, Adrian and Paula were asleep or going off to sleep, I decided it was time to explain another household rule. Although I felt sorry for Tilly and what she’d been through, it was important I established our rules, as I do for all the children and young people I look after.

With my dressing gown on, I went round the landing and knocked lightly on her bedroom door. There was no reply. ‘Tilly, can I come in?’ I asked quietly.

‘Yes,’ came her small reply.

I opened the door. She was lying in bed, her phone in her hand.

‘I think you should get some sleep now, love. It’s late and I like all phones to be switched off for the night or left downstairs. It’s a rule that applies to everyone in the house so we don’t disturb each other and we all get enough sleep.’

‘It’s my friend,’ Tilly said, as if that made a difference.

‘But I’d still like you to say goodbye and then speak to her tomorrow. When school starts again you won’t be up this late.’

‘OK,’ she said.

I returned to bed, her phone went silent and eventually I fell asleep. I never sleep well when there is a new child or young person in the house. I’m half listening out in case they wake, frightened, not knowing where they are and in need of reassurance. It didn’t matter that Tilly was fourteen and had assured me she’d call out if she needed me; I was still worried about her, and when I wasn’t, I was worrying about Lucy.

However, Tilly did sleep well and as far as I knew was still asleep the following morning. I was up first, as usual, followed by Lucy and Adrian, who had to go to work. At 8.30 Tilly came downstairs, dressed. The graze on her cheek looked much less angry. ‘I don’t think you’ll need to see a doctor about that, do you?’

‘No, and I’ve got to go out now.’

‘Why?’

‘Mum’s just phoned me. She’s upset. Dave’s not there, he’s gone to work.’ One of the downsides of mobile phones for young people in care is that this type of contact cannot be controlled. I had concerns.

‘Your social worker said she wanted you to meet your mother away from your home, and to wait until after she’d spoken to her.’

‘I can’t. Mum needs me now,’ Tilly said, with an edge of desperation.

‘Is she in danger?’ I asked.

‘No, but she’s very upset.’

‘I think you should wait until you’ve spoken to Isa. What if Dave comes home and finds you there?’

‘He won’t, he’s at work. Mum needs me,’ she said again. ‘Don’t worry, I can take care of myself.’

I wish I had a pound coin for every young person who’d told me that! I’d be very rich indeed.

‘She really does need me,’ Tilly persisted. ‘Sorry, I need to go.’ She turned and headed for the front door.

It was clear I wasn’t going to be able to dissuade her and she was too big for me to stop, so reluctantly I had no choice but to watch her go. Foster carers are not allowed to lock doors to stop a child from leaving, but I was concerned that Dave might suddenly appear, and this type of contact was against her social worker’s wishes. It also crossed my mind that this could be a trap to entice Tilly home. Her mother was in Dave’s control and he was angry. I wouldn’t have excluded any possibility. Years of fostering has taught me to expect the unexpected.

I now needed to report what had happened. As it was close to nine o’clock, I decided not to phone the emergency out-of-hours duty social worker, who probably wouldn’t be familiar with Tilly’s case, but to call Isa’s work mobile, which would be on during normal office hours. It wasn’t an emergency as such, as it is when a child goes missing. I knew where Tilly was going.