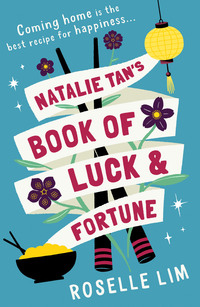

Natalie Tan’s Book of Luck and Fortune

“You left her alone for years. You knew she never went out. You knew this would happen! She raised you on her own and took care of you. This is how you repay her? You come back too late to be of use!”

I could say nothing to defend my actions. If I hadn’t left her, Mama would most likely still be alive. I’d have been there all along to ease the strain, or at the very least been able to call an ambulance for her this morning, when she passed. Maybe that would have made all the difference.

“You’re not welcome here. Get out of my restaurant.”

I lowered my spoon to the plate without making a sound and reached for the handle of my rolling suitcase. Eyes downcast, I pushed myself away from the table.

“Mr. Wu, please,” a familiar voice spoke, the same one from the phone earlier today. “Have some compassion. She just lost her mother.” Celia Deng stood beside me, her firm hand resting on my shoulder, resplendent in a navy frock with a white hibiscus pattern. She was five years younger than Ma-ma at forty-eight, yet despite their age difference, they were close friends. There was no trace of gray in her curled hair. Her subtle perfume smelled like cut gardenias. She continued in firm but gentle tones. “She must have arrived from the airport and wanted to get something good to eat. You can’t fault her for choosing your restaurant.”

Blood rushed to my face, bringing a welcome heat. Why was she defending me? Was this an act of pity? Old Wu’s harsh face softened. “If it was your idea, then I apologize.”

“I’ll take her home now. I’m sure she must be exhausted from her flight. I’ll pay the bill.” Celia squeezed my shoulder as a cue to leave. I reached for my suitcase and took my place beside her.

He cleared his throat. “No, it was my fault, Celia. Don’t worry about the bill.”

“No, no. Business is business, Mr. Wu. We all need to make a living.” She reached into her purse for her wallet.

“I refuse to allow you to pay for my error. Put your wallet away, Celia.”

“I’m one of your most loyal customers and I don’t want to lose my standing. Please, I insist.”

This was a familiar dance, and I’d have laughed if Old Wu were not involved. The tug-of-war to pay the bill was a common cultural occurrence involving everything from mad dashes to the till, to calling the restaurant or telling the server ahead of time who would be paying. In most cases, the end result required the server’s patience in waiting for the resolution. The performance of paying the bill demonstrated the traits of generosity and hospitality so prized by our culture.

Celia emerged victorious and left two crisp twenty-dollar bills on the table before she linked her arm with mine and escorted me out of the restaurant. Old Wu returned to his post without further comment. My heated cheeks remained the sole trace of the old man’s earlier tirade. The details of the incident might fade, but I would never forget the shame.

“I’m sorry about Mr. Wu,” Celia murmured. “He’s set in his ways and he doesn’t understand your relationship with Miranda. He’s probably still stinging from your laolao’s death decades ago.”

Old Wu was of the same generation as Laolao. Ma-ma had seldom spoken of her mother because their relationship had been complicated at best, but I’d always yearned to know more about my grandmother.

“He knew her?” I asked.

“Of course. Your grandmother’s restaurant was once the jewel of Chinatown.”

I unwound my arm from hers in surprise. Information about my grandmother had never flowed freely from my neighbors.

Celia smiled. “Qiao and Miranda loved each other, but both wanted very different things.” She paused. “Miranda asked us not to mention your laolao to you. I have honored her wishes until now.”

Ma-ma. I still couldn’t believe she was gone.

“How did it happen?” My voice dwindled to a whisper. If Celia weren’t in such close proximity, she might have missed it.

“It was the strangest thing. Anita Chiu found her outside your building, collapsed on the sidewalk. I still don’t know why Miranda stepped out.”

A sudden hope swelled inside me, mingling with the shame and guilt. Ma-ma’s agoraphobia had kept her confined upstairs. The building could have been on fire, and if she had to walk across the threshold for safety, she still wouldn’t have been able to. Had something changed over the years I was gone? “Was … She’d been able to leave the apartment?”

“No. It was so unlike Miranda. I saw her two nights before when I came for a visit. She looked fine then. A little pale but within the normal range for your mother.”

Why had my mother stepped outside?

I was thirteen, on my way to the bus stop, when I tripped over a crack in the sidewalk across the street, opening a deep gash in my shin. Ma-ma had seen the whole thing, her face plastered against the glass of the window, but she wasn’t able to come down and help me. The combination of sheer panic, anguish, and helplessness on her face was forever burned into my memory.

Why did you go outside, Ma-ma?

“It is a mystery to all of us. But the important thing is that you’re here now.” Celia paused to gather her breath before continuing. “Her body is at the morgue. I can go with you in the morning, and if you want me to, I can help you plan the funeral. Miranda wanted a traditional Buddhist ceremony. We can do a private one and rebuild your family shrine.”

“Family shrine?”

“You had one. I saw it once, but Miranda put it away after your grandmother died.”

Laolao died long before I was born. Ma-ma had only spoken of her as one would a favorite fable, presenting merely the morals of the tale and leaving the details vague on purpose. Guilt gnawed at me for wanting more than what my mother had given, but now that she was gone, the opportunity to know anything about my grandmother was lost. Regret flooded me: I should have pushed harder. Laolao was a part of me too.

“With your mother the way she was, I know you’ve never been to a Chinese funeral. Do you know what to do? Let me help you. It’s the least I can do.”

Celia’s kindness crept in to surprise me. Such was the vulnerability of grief: every act of concern was felt more deeply, for the path to the heart was clear. It mattered not who was offering, this was what I needed now, and I was grateful.

“Thank you,” I said. “I don’t know what to do or how to even begin arranging this.”

She patted my arm. “After having arranged the funerals for my parents five years ago, I know the ins and outs. I’ll be your guide.”

We stopped at the door to Ma-ma’s apartment. Celia gave me a tight embrace. “I’m really sorry about Miranda. Would you like me to come in with you?”

I shook my head. “I need to do this alone, but thank you.”

“I understand.” She nodded. “Oh! And before I forget, beware of the cat.”

“The cat?”

“I’ve been feeding the little piranha for Miranda. She picked it out a month ago. I was both delighted and supportive of her decision until Meimei drew blood. The kitten is very cute and only likes—liked—your mother. Don’t be insulted if she hates you.”

Meimei. Little sister. Ma-ma chose the name well. The idea of my mother having a companion made me smile. She should have done it years ago. My gaze drifted to the faded scratches on Celia’s forearms, which I hadn’t noticed until now. “Thank you for the warning and for everything else.”

“You have my number. Call me when you’re ready.”

Celia returned to her building and left me standing alone by the door to the apartment.

By the time I turned the key, climbed up the stairs, and stepped into my mother’s apartment, I was crying. A trail of sorrow followed me. When sadness made an appearance in my life, it always brought the weight of the ocean with it.

I locked the door behind me and set down my luggage in the foyer.

It was like traveling back in time—nothing had changed. From the bird figurines my mother collected to the small cracks in the pale lemon walls she had so carefully painted, it was exactly as I remembered. The layout of the apartment was modest by San Franciscan standards but generous compared to the closets I had lived in the last few years. Two bedrooms, one bathroom, a combined kitchen and living area, and access to a seldom-used rooftop patio. Three windows overlooked Grant Avenue and provided a clear view of the green tiles of the paifang, the ornate arch marking the edge of Chinatown at Bush Street.

I closed my eyes and breathed in the familiar scents of the apartment: oolong, jasmine, and tieguanyin teas held in vintage tins in the pantry; pungent star anises and red Sichuan peppercorns mingled with pickled ginger and dried chili peppers in the collection of spices above the stove; the musty scent of newsprint from the stacks of Chinese newspapers Ma-ma subscribed to; and the subtle perfume of phalaenopsis on the windowsills.

Home, but empty in a way I’d never experienced.

On the kitchen counter, a long envelope stuck out from one of the slots of the unplugged toaster. Ma-ma had never eaten toast in her entire life. She had bought the appliance for me because I’d loved peanut butter and jelly sandwiches on toast for lunch. The paleness of the crisp paper matched the shade of sliced bread. Ma-ma’s elegant script spelled out my name. The pristine corners betrayed its age: this had been placed there recently.

Goose bumps rose on my skin.

I picked up the envelope and ripped it open. My fingertips skimmed the rippled surface where the pressure of Ma-ma’s pen had marked the paper. My heart clenched, squeezing inside my rib cage like a captured bird. Written on sheets of onionskin were my mother’s last words to me.

Dearest Natalie,

I had imagined your homecoming to be full of joy, sugared fritters, and late nights listening to the tales of your travels. I wanted to hear your stories and all about the new dishes you’ve tried.

I attempted to write you this letter every year, and until now, I could never finish it. At first, it was because of pride: I wanted you to come to your senses and come home because you knew I was right. Then as the years grew longer, I didn’t care anymore about who was right or wrong. I shouldn’t have allowed the silence between us to stretch on for so long. I never reached out because I was afraid that you didn’t love me anymore.

I love you so much.

I’m sorry.

I’m sorry for not understanding your wishes.

I’m sorry I tried to impose my will on you.

I’m sorry for all the hurtful things I said, that you would never cook like your grandmother, words uttered in desperation and spite.

These were my fears. I pinned them onto you, hoping you’d claim them as your own and abandon your dream. I wanted you to stay close to me. Instead, I lost the very person I loved most in this world.

I will always love you, dear heart.

Your presence in my life helped me forget its fractured state: my heart has been broken since before you were born. I fear it will be my undoing, but I have accepted this. It’s my burden and mine alone to bear.

Before you came into this world, your grandmother and I quarreled, just as you and I have done.

She wanted me to be someone I’m not, just as I tried to do the same to you.

You should have the freedom to choose your own way. I understand this now. You are more like your grandmother than I was willing to admit. And that isn’t a terrible thing by any means.

Your grandmother helped build this community. She came from China with nothing but her mother’s wok and the cooking skills she had learned from her own mother. All by herself, she opened a restaurant, and her dishes brought people together: strangers, bickering relatives, newcomers, and old-timers alike. Her establishment welcomed all and was the jewel of Chinatown.

But I refused to honor my mother’s legacy.

Because of this, I have watched the street die. The neighbors are struggling to keep their businesses afloat. They will lose everything they have worked so hard for. If your laolao’s restaurant were still open, this would never have happened. People came from miles around to eat there. She kept the neighborhood alive.

I lied to you about the restaurant. I told you that it was in a horrible state of disrepair. I did this to dispel any illusions you might have had about running it. But I was wrong to turn you away from what you sought.

If you want to reopen the restaurant, you have my blessing. It is dirty and dusty but still operable. Perhaps it is your destiny to follow your grandmother and save the neighborhood once more. Follow your dreams, beloved daughter.

Love,

Ma-ma

The letter was dated yesterday. It fluttered to the floor as I braced my palms against the counter.

I wished her written words could have taken to the air and shattered the long years of silence between us. What she said about my cooking, all those years ago, had left lingering scars. I’d wanted to prove her wrong, and yet I still hadn’t accomplished my goal. I’d been so angry that I allowed myself the luxury of reticence until it became a habit.

If only my pride hadn’t kept me away from her while waiting for an apology that never came. If only I had treated her as if she were the fickle clouds dispersed by the winds, instead of the eternal mountains. Clouds were mutable, mountains immovable. If only.

I wandered into the living room and sank into the faded sofa.

You are more like your grandmother than I was willing to admit. My mother had seldom spoken of Qiao. For years, I’d yearned for any memory Ma-ma could afford to give. But I’d never begged, for thinking of her seemed to bring my mother pain, and I’d loved her too much to press.

Ma-ma had also seldom mentioned my father, but I never wanted anything to do with him. My mother’s anger toward him had become my own, an inheritance I welcomed as a reaction to his abandonment.

My fingers dug into the cushion, squeezing the thinning foam underneath. And the restaurant. It had been boarded up on the first floor, forbidden to me because it was too dangerous to enter. But now I knew: my mother had lied when she told me it was ruined beyond all repair. My dream had been right beneath her all these years.

She wanted me to follow my dreams.

I broke into sobs, my chest heaving, gasping for breath from the pain of loss. My teardrops formed tiny crystals and fell hard against the linoleum. The ache within my rib cage swelled with every gulp of air.

As I cried, my gaze fell upon the wooden lotus-shaped bowl on the coffee table. Bought at a flea market, the bowl’s subtle wood grain reminded me of melted chocolate. It served as a replacement for the ceramic bowl I had accidentally broken before leaving. I traced its rounded petals before dipping my fingers inside it, into a small sea of teardrop crystals. Ma-ma had collected my tears since birth: first saving them in silk pouches, then graduating to bowls. I hadn’t understood why she’d wanted to keep them. She told me that she always wished to keep a part of me with her, and that there was beauty to be found everywhere—even in sadness. When Ma-ma cried, her tears took days to dry, leaving salt trails in their wake. The fragile salt disintegrated into nothingness.

Where was the piece of her I got to keep with me? Everywhere I looked I saw reminders of her presence, but nothing rivaled the power of her last letter lying discarded on the kitchen floor. I rushed to pick it up, pressing it tight against my broken heart. There was nothing I could do to bring her back.

When I finally stopped crying, I gathered the tiny crystals into my hands, pouring them into the bowl on the coffee table to join the others. A stray sunbeam struck the center, illuminating the ceiling with dancing prisms. I marveled at the display. Ma-ma always found the beauty in unlikely objects.

A soft meow interrupted my thoughts. A powder-puff-shaped creature emerged from the hallway. A pink rhinestone collar sparkled around her neck, complementing her glacial blue eyes. Meimei? I had almost forgotten about Ma-ma’s kitten.

She approached me without hesitation and rubbed herself against my calves, weaving in and out of my legs until I bent down to scoop her into my arms. Her snowy fur was softer than I imagined. I carried her to the high-backed chair. Sitting down, I lifted her to my face so our eyes could meet. She batted my nose in defiance.

“Hello, Meimei. You and I loved her the most, and now we have to start grieving her.” Sorrow swelled in my throat, cutting off my words. I held the cat against my chest and sighed. Purrs emanated from her tiny body, waves of vibrations that washed across my skin like the most comforting of massages. I held her closer and smiled when I noticed she had dozed off.

“Oh, little one. You have me now.”

Perhaps a part of my mother remained after all.

Chapter Four

My mother had given me her blessing, which meant I’d left in search of a dream that was right here at home the whole time. The restaurant. I needed to investigate. The cat batted my ankles as if she concurred with my sense of adventure. I bent down to pick her up and take her with me.

The door to the restaurant was at the base of the stairs leading up to the apartment. I pushed the door open and fumbled for the switch. Light flooded the narrow galley, which was flanked by cupboards and counter space on one side and the stove, oven, and fridge on the other. Just as my mother had said, it looked to be in perfect working order, with enough room for one person—the cook. It was in many ways comparable to the cha chaan teng—tiny counter service restaurants—I’d worked at in Hong Kong.

This was where Laolao had cooked for her neighbors all those years ago. She’d spent most of her life walking up and down this galley kitchen. She was here.

She’d learned how to cook from her own mother and hadn’t gone to a fancy culinary school. If she could do it, perhaps I could too.

This was what I’d always wanted. This could be mine.

The realization settled in between my shoulder blades, in a spot I couldn’t reach or ignore. I’d thought that as long as I kept moving, working in kitchens, and traveling, I had a goal. But Laolao had had true purpose. She had known she wanted to cook, and she’d achieved great things. Ma-ma had had purpose too. She had embraced motherhood and become the sole parent I had needed and wanted.

I had always wanted to cook. What better way to pursue my dreams than to literally follow in Laolao’s footsteps? Could my purpose be right here at home after all? Ma-ma had not only denied me this—she had concealed the restaurant’s condition from me all along. But there was no point in being angry at ghosts.

My skin itched from the stale mustiness clinging to the air. A thin veil of dust covered every surface, reflecting ages of neglect; much like the patina on Ma-ma’s bronze birds. Dust caked my fingertips when I skimmed them across the counter.

My initial excitement was soon replaced by doubts. Most new restaurants struggled to survive their first year. Even with the humble beginnings I envisioned, reopening the restaurant would still cost money I didn’t have. I strolled toward the front of the restaurant, flipping the switches, turning on the pendant lamps. The lights continued to work after all these years, proving there was definitely more than a flicker of life left in this place. The dining area, annexed in part by the stairs to the apartment above, included four wooden bar stools and two square tables.

The space was bigger than I’d thought it would be: I had expected only counter service. I walked to the picture windows, covered by plywood, shuttered as if prepared for a hurricane. A chalkboard hung on the far wall where swirls of white marred its green surface, remnants from the damp rag used to wipe it clean.

Oh, to have been here to see what this place was like in its glory: to smell the aromas from the kitchen, to hear the roar of the hot oil and the hiss of the steamer against the chatter of the customers, and the sounds of the street in the bells of the cable cars and traffic zipping by.

If my regrets and wishes were fireflies, the brilliance of their dance would turn night into day.

I walked to the main door and removed the coverings from the glass.

The cat’s meow drew my attention to the counter. She was batting a heavily draped object about two feet tall, sitting on the counter near the wall. I walked closer and unwrapped the woven striped runner rug that was tucked around this mysterious item. My fingers searched for the edge of the fabric, tugging to pry it loose without disturbing what lay underneath. The rough textile chafed my skin as I unraveled the rug.

It was a statue, dark with the discoloration that had set in over time. Unlike bronze figures whose tarnish only enhanced their beauty, this taint created a darkening cancer. Craters pitted the surface like the scars of the moon, pockmarks rendered in metal. The sculpture’s sadness, and uneven features, were familiar. Guanyin: the goddess of mercy and compassion. A revered goddess shouldn’t be treated this way.

It was odd that Ma-ma, governed by her superstitions, had done nothing about this.

Of course, I didn’t believe my mother’s fears or the many demons that rode on the back of them. Demons weren’t real. They were ghost stories meant to frighten children. It was very sad that my mother hadn’t been able to understand this.

Still, in her honor, I would make this right. I touched the gouged surface of the statue, my fingers tripping over the pits. Maybe one day I could see her restored.

Meimei meowed, hopping off the counter to stand by the door, where someone was waiting. It was nine in the evening and no one, aside from Celia and Old Wu, knew I had returned. An ash blond woman in her late forties rapped her knuckles against the glass door. She was too well dressed to be a burglar and too professional in her powder blue suit to be a lost tourist.

“Not open,” I said in a loud voice, over-enunciating the words in case she failed to hear me.

She held something white against the glass with her palm. A business card.

I walked toward her to get a closer look. Melody Minnows, realtor. The picture on the card matched the woman at the door, right down to the shade of mauve lipstick and diamond hoop earrings. I repeated that we were closed.

She dove into her oversize purse, retrieved a sticky notepad and a pen, jotted something down, and pressed the note against the glass. I’m sorry about Miranda. How is Meimei doing?

This woman knew my mother. I let her in.

Chapter Five

Melody smiled and murmured her thanks.

“You knew my mother?”

“Yes, we spoke a few times. She invited me upstairs for a cup of coffee. That’s where I met the cat.” Melody crouched down and held her hand out to Meimei. The cat hissed before running into the kitchen. “When is the funeral?”

“Soon. I still have to figure out the details.”

“Ah, of course.” Her perfect smile never faltered. I wondered if she had trained herself in front of a mirror. “It’s a lot bigger than I thought in here—the blueprints don’t do it justice! The last time we talked, Miranda was contemplating selling. I told her the market was perfect, and I have several buyers already interested. I know I can sell it over asking. Everyone is looking for office space, and this is a hot location. We’ll have to move fast before the planning committee changes the bylaws. This is prime commercial space.”

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.