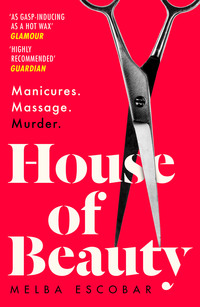

House of Beauty

Recalling it now makes me chuckle. The first one tasted awful, but the next ones were a riot. That’s the kind of thing that happens when I’m with Claire. It’s like, let’s see, we’re the same age – I think I might even be a little younger – but next to her I feel so straight-laced. In contrast, she’s independent, liberated. Youth is definitely a mindset. On top of that, she’s heading towards sixty and is still stunning, absolutely stunning.

So, getting back to Eduardo, I met him when I was twenty-five. According to him this meant that, as a woman, I was in the prime of my life. He was thirty-seven. Until then I’d been a bookworm. My mother died when I was eleven. I was always quite ugly. In any case, I was never a beauty. I didn’t know much about men, and what I knew about relationships came from books. I decided to become a psychoanalyst because I grew up listening to my father talk about his cases, so it seemed the most natural thing to do. I don’t believe I even considered other options, though now I think I should have studied biology.

And so I met Eduardo at a conference. He seemed relaxed. Later I’d think frivolous. He seemed sure of himself, as though he had no need to impress anyone, though with time I’d come to interpret this as narcissism. While narcissism is a natural part of the human make-up, whereby any discovery that refutes one’s self-image is rejected, Eduardo takes this to the limit. He verges on sociopathy, a diagnosis that has taken me almost thirty years to arrive at. At least I devoted myself to writing and not to my patients. It’s possible the poor things have had a terrible time with me, since it takes me years to arrive at a diagnosis. But anyway. Speed has never been my thing. I was struck by the fact that a fine-looking man like Eduardo would notice me. I’ve always been full-bosomed, maybe that’s what attracted him. That and the manuscript, or the fact that I was always very understanding and maternal with him. I still remember the time he called me ‘mami’. He was distracted, leafing through the newspaper; I asked him something – whether he’d booked an appointment with the urologist, something like that – and, not lifting his gaze, he said, ‘No, mami,’ and then went bright red with embarrassment. I burst out laughing.

We got married a year after we met. I’d only been with one man before him, in a relationship as strange as it was uncomfortable for the both of us. I was head over heels for Eduardo. I couldn’t believe such a dish had looked twice at a woman like me. And as well as being good-looking, he was fun, witty, self-assured, worldly, classy – in other words, everything I wasn’t. As something of a dowry, you could say, I offered him a manuscript, which he published to great success. It was a book about the kind of love that kills. He thought it was extraordinary and only proposed a few changes. He published it under his own name, and mine – Lucía Estrada – wasn’t mentioned anywhere. I must have been spellbound by Eduardo because it’s not that I didn’t care; it actually made me proud. All I could think was, He liked it so much he published it under his own name. I couldn’t believe it. And then I wrote another book, which he again published under his name, but this time I’d said, ‘Look, my love, truth is I’m no good at giving interviews, at responding to emails, at explaining the theories put forward here. So, if you want, you keep signing your name.’

And to my surprise he’d said he’d be happy to. I was sort of hoping he would say, ‘No, my love, you can do it, you deserve the recognition, how could you think I’d sign for you.’ But that’s not what happened. Three decades and sixteen books later, Eduardo is the second-most-prominent self-help author in South America. And we all know who the number one is.

At the start of our marriage, having a child was up for discussion. He hadn’t closed the door and I thought that he’d keep it open for me. But no. He didn’t want children. Nor did he want to live abroad, because here he had his fans and his business associates. I kept writing the books. That, at least, took me to all different places. He gave talks, I wrote. He signed books, I wrote. He went shopping, I wrote. He spent the weekend with a lover, I wrote. And that’s how it went for thirty-three years. It’s not like I’ve really suffered or anything. I’ve lived comfortably. I like books; I feel secure, calm around them. I’ve had a good life. Plus, I loved Eduardo so much that his happiness was also mine. And we had things in common, though in all honesty he didn’t much like talking about books. Actually, I’m not certain what bonded us, exactly – cooking, maybe, as he knew how to make three or four dishes, and when he cooked he talked to me about what he was doing. I’m not sure what we did together all those years, but I didn’t feel bitter, or unhappy. None of that. It was only when we separated that I came to a diagnosis: the neurotic patient, in this case Eduardo, fashions his world into a mirror, and expects a response that reflects his own expectations about himself. In other words, the patient sees his wife, his friends and his work as projections, his idealisations of what they should be. In this way, he doesn’t recognise the other as an independent being, because the other only exists as a reflection of his own unsatisfied needs. When the inevitable failure of an idealised expectation occurs, an irreversible frustration overcomes him, giving rise to the process that Freud, following Jung, calls ‘the regression of libido’. This is how I lived for three decades with a man who never knew me nor wanted to get to know me.

He was a man for whom the important thing was feeling loved, admired and respected by an anonymous but irrefutable mass. My existence was important to him only in that it continued to validate his sense of self.

The fact is, in my own way, I was happy. I suppose that my happiness consisted in the ‘negation of my own desires’, in ‘renouncing myself’ and even in ‘self-punishment’: Claire’s words. I served him well, in all senses of the word. The ironic thing is, I still serve him. Before finalising a divorce settlement, I moved to a small apartment in La Soledad, where I still write books for Eduardo, in exchange for a monthly allowance and the occasional furtive encounter, almost always infelicitous. He still seems to me drop-dead gorgeous, and funny, and so refined; he’s as adorable as they come. Though, as I said, I haven’t felt desire for a long time. The point is that Eduardo suffered a lot as a child. His father mistreated him, and he had to learn to put up defences, to protect himself. We shouldn’t be so quick to judge others. And that’s what I told Claire. No one is as good or bad as he or she seems. Eduardo was never a bad man. Although, there’s some truth to the idea that I became more and more a mother figure. Yes, a mother figure. I brought him his slippers. Made him coffee. Ran his bath. And he turned to me for comfort, for reassurance. My poor Edu.

The last time we saw each other, he tried to kiss me. We’d been to dinner at a new restaurant. He brought me home and asked if he might have a drink before he left.

‘I’m tired,’ I said, trying to get out of it.

‘Just one glass, my Lu-chia.’

One glass turned into the five or six that were in the bottle and a never-ending monologue. I nodded off at the other end of the sofa. Eduardo wanted to talk about his impotence, then leaned over to kiss me, and I pushed him away.

‘I can’t, my love, I’m sorry,’ I mustered the energy to tell him.

‘You can’t or you can’t be bothered?’ he asked, lighting a cigarette, not looking at me.

In the cold early hours of 23 July, he woke on the couch. I had settled a blanket over him before going to bed. I fell asleep at almost three in the morning and two hours later heard him. But what was he doing? I wondered this in a half-awake state, because I could hear him tripping and moving about in the little living room while murmuring into his phone. A loud thud got me out of bed. I went out to see what was happening. Eduardo was searching for his shoes in a rush. The living room was still in semi-darkness. He had knocked over the bottle of whisky and the little that remained had spilled onto the parquetry floor.

‘What’s wrong?’ I asked, alarmed.

‘I’m sorry, Lucía, I have to go.’

‘So early?’

‘A friend’s in trouble, he needs my help, I’ll tell you about it later.’

Eduardo left. Right away I emptied the ashtray of my ex-husband’s butts. I wondered how it was that someone over sixty could have a friend in trouble at this time of the morning. It could happen in adolescence, but at this age? It reminded me why I left him. Eduardo was selfish and, forgive me, thought more with his willy than his head. How I hated the smell of cigarettes. One of the good things about my new place was that no one smoked here. That, and the silence, the peace. I bought a yoga book for beginners, a special mat and a few candles. Eduardo made fun of me. He thought it ridiculous that at this stage of my life I wanted to learn something new. Every afternoon I dedicated an hour to it, and bit by bit improved. The simple fact that I didn’t have to accompany Eduardo on his trips any more gave me lots of freedom. One or two afternoons a week, I went to the cinema, sometimes for long walks down Park Way. I even thought about getting a dog.

I got out a slice of bread and slotted it into the toaster. Mopped the parquetry floor. The smell of whisky nauseated me. I opened the windows. Prepared a coffee, watered the plants and brought the laptop to the dining table to go over what I’d written the day before. I served up the toast and coffee, put my glasses on and started to read: ‘This is how infidelity becomes the most common reason behind divorce and marital maltreatment. It can cause depression, anxiety, loss of self-love and many other psychological disturbances, representing the dark side of love.’ I read it twice. It made me laugh. I couldn’t read it again. The Dark Side of Love could be describing the two of us. I felt listless. What would happen if I didn’t write the book? The royalties from the others would be enough for us to live off. True, there was an existing contract for The Dark Side of Love and it was scheduled for release next year. But Eduardo could always find another ghost writer: nowadays there were a lot of decent young writers around, and some of them had studied psychology.

And he seemed to be doing very nicely from the business he had going with his associate. It wouldn’t matter in the least if we didn’t publish a book; it wasn’t as though we would starve. Though Eduardo was becoming increasingly ambitious. Greedy, you could say. In fact, that had been another catalyst for our separation. His plans to buy a place in New Hope, on top of the Gloria incident, were the last straw. It didn’t matter how much I criticised New Hope’s flashy Miami look, with all its showy pride at being the most expensive postcode in Bogotá. He’d insisted that we would be comfortable living among ‘people like us’.

‘People like us? And at what point did you become a prototypical, snobbish Colombian?’

‘Don’t start with me, Lucía,’ he’d said. ‘Anyone would think you were penniless.’

The conversation hadn’t lasted much longer. He argued that there was nothing wrong with wanting the best.

‘We deserve it, my Piccolina,’ he’d said.

He’d pulled out a green folder from his leather briefcase then opened it slowly and pulled out some papers.

‘Piccolina, the matter is already settled. All you need to do is sign here, and we’ll have made the best investment of our life.’

Eduardo leafed through the papers and started reading out loud and telling me about the property. ‘You have to see the vertical garden on the rocks out the back. There are 350 car spaces, a security room, 48 security cameras.’

He kept reading. ‘You’ll love the function room, my love, it has its own kitchen. And amazing furniture – all designer, very tasteful. But the best part is the clubhouse. You like swimming, you’ll love it. There’s a climatised semi-Olympic pool, with a swimming instructor, sauna, steam room, Pilates room …’

The phrase ‘you like swimming’ had echoed in my ears. The truth was, I did. I had liked swimming as an adolescent, and I had at university, too. Why had I stopped swimming? ‘You like swimming’ echoed in my head again and again until I felt like I was drowning.

I also liked Joan Baez and Simon and Garfunkel, I liked heading to the mountains on weekends, I liked preparing ajiaco soup – but Eduardo didn’t eat ajiaco, didn’t like my music, and if he left Bogotá it had to be by plane. So, I’d adapted my preferences to suit his, and I’d adapted so much I’d become blurry. He finished talking and, not noticing my red eyes or my silence, he put the papers back into his briefcase, changed his jacket and dabbed on some cologne.

‘Goodbye, my love,’ I said with a smile from the bed.

‘Don’t eat too much,’ he said.

I got into bed with a bag of potato chips and a box of chocolates. By midnight I’d watched an episode of CSI and two of Mad Men, and I was tired. The women in those series are heroines, I thought, but, in the end, it never does them any good. Eduardo still hadn’t come home. My eyes were swollen from crying.

When I turned off the TV I imagined sleeping in another bed. A smaller one, but my own. I fell asleep thinking about a window overlooking the street, hopefully alongside a park, an open-plan kitchen, a few plants, a round dining table and a little lamp hanging above it. Eduardo came back when dawn was breaking. I was up and sitting in front of the computer, looking for apartments in La Soledad.

‘Up working so early?’ he’d said.

‘What do you think?’ I’d said, determined to find the perfect place for myself, the room of my own where there would be no space for him.

And now I was in that place of my own, collecting his cigarette butts. When I finished cleaning, I decided to ask Claire if we could make a habit of catching up once a week. I decided not to let him smoke at my place again. I raised the calendar and marked the date: 23 July. From this day forward, no one smokes in here, I said to myself, circling the date with the same red pen that I used to correct drafts of his books.

5.

Sabrina was in her uniform. That’s why they didn’t let her into the hotel bar where she was meant to be going on her date with Luis Armando. She would have liked to go for a drink, or for him to take her to a restaurant, or at least to go for a walk. But he insisted on seeing her in his room.

‘I can’t wait to cover you in kisses,’ he said.

And that phrase was enough for Sabrina to feel her heartbeat quicken.

‘Do you love me?’ he asked in the voice that often murmured over the telephone how much he wanted her.

‘A lot,’ Sabrina said, turning red. It was the first time a man other than her father had asked.

When she went up to his room, she saw that Luis Armando was drunk. She was drunk, too, from the brandies she tossed back earlier so that she could bear the pain of the waxing. If she’d been sober, perhaps she would have reacted faster. But she wasn’t. She realised that coming here hadn’t been a good idea. Nevertheless, instead of leaving, she stared into his eyes, searching for the spark of love she thought she’d detected in them once. She was ready to become a woman.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Полная версия книги