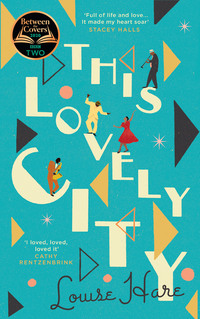

This Lovely City

‘Cary Grant, eh?’ She busied herself tidying the supplies away. ‘I don’t know about him but there’s quite a few chaps with dark hair round here.’

‘True,’ he agreed. ‘And you lot all look the same to me.’

She laughed. ‘Yes, well, I shall remember that when you walk past me in the street next week and don’t give me a second glance.’

‘As if that could happen!’ Was he flirting with her? He’d never been much good at it before but she was smiling. Maybe some of Aston’s charm was rubbing off on him.

‘Have you found anywhere to live? After you leave here, I mean?’

‘Not yet. I need to find a job first.’

‘What job did you have back home?’

‘Nothing. I mean, I was studying.’ He glanced up at her, wondering if she thought him just a child. He wasn’t sure how old she was. Probably older than his nineteen years if she was married. ‘My mother wanted me to go to university but money was tight so, you know, here I am. Come to London, seeking my fortune.’

Rose giggled. ‘You sound like Dick Whittington. And I’m sorry but these streets are more likely paved with rubble than gold.’

‘I noticed.’ He sighed. ‘Still, a few of the fellas think maybe we can actually get a band together and earn money from it. I play clarinet. My father always wished he’d become a professional musician instead of working in an office. I suppose I’d like to fulfil his dream now that he’s gone.’

‘You’re lucky,’ she told him, ‘to have something like that, something you love. I worked in a factory during the war, believe it or not, and I loved it. We had a right laugh and I felt like I was doing something proper, you know? Something useful. But Frank, that’s my husband, he wanted things to go back to normal when he came home. Married women don’t work, he says, not unless they need the money, it’d look bad on him. He doesn’t even like me doing this only I insisted. So long as his tea’s on the table when he gets home from work I reckon he can’t really complain, and he’s in the pub most nights anyway.’

‘You don’t look old enough to be married, you don’t mind me saying.’

She smiled. ‘No? I suppose not. We got married straight out of school. Frank was heading off to war and we knew there was a chance that…’ Her voice trailed off.

‘You were lucky,’ Lawrie said. ‘He came back.’

‘Yes.’ She took a step backwards, away from him. ‘Anyway, you’re all done. Pop up in ten minutes if you want feeding before you head out. And curfew is midnight so don’t be late back.’

‘Thank you.’ He held out a hand and she shook it.

‘D’you think you’ll stay long?’ she asked. ‘In England, I mean.’

‘I should think so,’ he replied. ‘Don’t you read the paper? This is our home now.’

‘Then welcome home,’ she said.

13th March 1950

Dear Aggie,

I do hope all is well? I just got your letter and I have to say you’ve got me worried about you, darling sister.

If you want my advice, and your letter implied that you did, I think it’s time to let Evie stand on her own two feet. She’s eighteen after all. We weren’t still living at home at her age, were we? And she won’t have it half as bad as you did! She’s got you and that young friend of hers – Delilah or whatever. That boy next door, when’s he going to come good and get down on one knee? You should have a word with him, like Ginny Leyton’s dad did to her young chap years ago. He was down that aisle faster than a whippet round the track at Wimbledon! Of course, nobody would be foolish enough to mess with old Leyton but I reckon you could give him a run for his money.

Besides Evie and all that, how are you? Is everything all right? We shouldn’t leave it so long between visits, you and me. I did love seeing you so last year, both of you, and it does get a bit lonely out here on my own. Who’d have thought I, city girl through and through, would end up living alone at the bottom edge of a Devonshire village? You should come down this summer, stay as long as you want, there’s plenty of room. Don Waters was asking after you when I saw him last. You remember him? Bought you a half a shandy that night we went to the pub?

Anyway, I look forward to hearing from you soon.

Gertie xx

4

Evie had left the kitchen door open so that she could feel the draught if her mother returned earlier than expected. Ma had run out to deliver a dress that she’d taken up for a woman over in Stockwell, so she wouldn’t be long. It wasn’t that Ma was against Lawrie as such; he was allowed to accompany Evie to the Astoria, and they were allowed to go out for a Sunday afternoon stroll in the park, but she’d never allow this, the pair of them huddled so close together that an ant would have struggled to find a path between their bodies.

Lawrie leaned on Evie’s shoulder, his head lolling against hers more out of exhaustion than any amorous intention. She’d never seen him like this, quiet and staring into the distance. Nothing she’d said so far seemed adequate and she felt as though she was just repeating the same inanities over and again.

‘They can’t honestly believe you had anything to do with it. I mean, they don’t have any evidence. Nothing links you to any baby, let alone that poor child. They’re just desperate. They need to look as if they’ve done something. Taken some action.’

‘He didn’t want to let me go,’ Lawrie reminded her. ‘If that other fella hadn’t come in, I reckon I’d still be there, sitting in one of those cells he told me about. It wasn’t his decision, you know. He wasn’t happy about it.’

Evie lit a cigarette and took a deep drag while she tried to think of something better to say.

‘Bad habit.’ Lawrie shook his head as she blew out smoke, though she was careful to angle her breath away from his face.

She grinned. ‘I never had a dad before and I don’t want one now, thank you very much.’

He put his arm around her shoulders and she leaned into him, pushing her nose into the wool of his coat. The wool held the scent of smoky bars and a faint hint of woody cologne that had belonged to a previous owner. He was a gentleman, was Lawrie Matthews. Too much so sometimes. He never made a move on her, was careful where he put his hands even when she could tell that he was holding himself back. ‘Sorry I don’t have much time tonight.’

‘Don’t worry about me. Only you shouldn’t be going out, not when you’ve had such a shock. You look exhausted. Like you could fall asleep standing up.’ She reached up and caressed his jawline; he hadn’t even shaved, which was most unlike Lawrie.

His chuckle was frail, the ghost of a laugh. ‘I wish I could tell Johnny that I’m staying home. If I could, I’d stay here with you. We never seem to get any time to ourselves these days.’

‘What about tomorrow?’ she asked hopefully. ‘Delia and I were talking and it seems ridiculous that we’ve never had a night out at the Lyceum. I know you’re playing, but you’ll have breaks, won’t you? I can come backstage and you can show me around.’

‘Your mother will let you?’

‘I don’t see why not.’ She sounded more confident than she felt.

‘And you’ll tell her that I’ll be there too? I don’t want her to think we’re going behind her back or she’ll not let you out again until we’re married.’

Evie’s heart almost stopped as he reached the end of his sentence. Was she reading too much into a single word? He squeezed her tighter and she threaded her fingers through his and tried not to show him what she was thinking.

‘I think Ma’s decided that she likes you, you know. She asked after you only this morning. I think she just likes to put on a show, making sure we don’t get ahead of ourselves.’

‘Conniving woman.’

‘Just be glad she hasn’t taken against you. If she had then she wouldn’t leave this house without locking me in my bedroom first.’ It was an exaggeration but not far off the truth. Evie had let her mother down before and it had taken months to earn back that trust.

‘She’s not so bad.’

‘She has her moments.’ Evie tilted her head towards his until he got the message and kissed her properly.

‘You think the baby’s mother is someone like yours?’ Lawrie pulled away first, his mind elsewhere. ‘I mean, a woman in a similar predicament, if you know what I mean.’

‘Left holding the baby after some chap’s done a runner? Only maybe she knew better than Ma did and got rid?’

‘Evie, I’m sorry, I didn’t mean…’ His face was stricken with remorse.

‘It’s all right.’ She waved his words away as if they didn’t bother her. ‘Everyone else will be thinking the same anyway. It makes sense.’

She’d picked up a Standard on the way home but Lawrie had been able to tell her more than the short, hurriedly filed report. The paper hadn’t divulged that the baby was coloured but they had given an age. Evie had assumed on first hearing that the baby must be a newborn but apparently she – the baby girl – was almost a year old. Someone had cared for her for months before her death, had kept her fed and clothed and probably even loved her. Evie couldn’t imagine what must have come over the person responsible, to suddenly do such a thing. A baby was a precious gift. Not everyone had a choice in the matter, Evie knew, but Ma had coped on her own. And, as Delia had pointed out, there were institutions for babies who couldn’t be cared for at home. None of it made sense.

‘Do you think it could have been an accident? We’re assuming the worst but the baby could just have been ill. Maybe the mother panicked and didn’t know what to do. You said the blanket looked hand-embroidered.’

‘With flowers,’ he confirmed.

‘So somebody cared. Sometimes babies just die and it’s not anybody’s fault.’ Evie’s hand shook a little as she lifted the cigarette to her mouth.

‘What if it was someone we know?’

For so long the only other coloured person Evie had ever known was an intensely serious engineering student from Nigeria who had lived on the next street over when she was fourteen. He’d spoken to her sometimes if they’d been waiting at the bus stop, just chit chat, but she could sense within him the same loneliness she felt, knowing that she didn’t quite fit in. She’d never told him that her father had also been a student, just like he was. She worried that he’d ask her questions and she’d have to admit that her mother refused to talk about him at all.

‘How dark was her skin?’ Evie asked. ‘Darker than mine?’

‘I don’t know. It’s all mixed up in my head. If it weren’t for that Rathbone fella telling me that she was coloured I’d think I’d imagined it. I can’t believe that anyone we know would have done this, can you?’

‘’Course not.’ Evie ground out her cigarette on the step. She’d have to remember to take that in later and hide it in the bin, else Ma would have words. ‘You know, there are plenty of local women who’ve had a little secret flirtation. I mean, look at Aston. How many women have you seen leave on his arm at the end of a night?’

‘Aston? That’d be even worse. An awful lot of fellas round here would not like the idea of one of their women being with one of us darkies.’ His mouth twisted into a grimace as he spat out the slur.

And if anyone knew about that it was Lawrie, Evie thought, suddenly sour. ‘You think there’d be trouble?’

‘Let’s just hope that it turns out like you said and the baby died of measles or some such illness.’ His lips brushed her forehead and she knew he didn’t want to talk about it any longer.

Evie’s grandfather had been in the police, not that she’d ever known him. Ma had gone alone to his funeral and afterwards they’d moved into this house – his house – which had been the Coleridge family home when Ma was a child, before she’d been thrown out for getting pregnant and bringing disgrace upon the family name. Evie had never really understood how a man could choose so easily to cut off his own flesh and blood, but she’d learned to give up asking questions after Ma had told her that if she brought the subject up again, she’d take her down to the graveyard and leave her there by his headstone until she got her answers. Ma did keep one photograph of the man on the mantelpiece, dressed in his full police uniform. His stern expression made her glad she’d not had to meet him. The thought of a man like that going after Lawrie made her feel sick.

She checked her watch. ‘Ma’ll be home soon. Are we just going to sit here talking?’ She placed a hand on his thigh and felt him jump as though burned by her touch. ‘You don’t want to…?’

‘I just – I don’t want you to feel like you have to is all. Not on my account.’

‘Will you ever stop thinking of me as a little girl?’ she snapped, her tone sharper than she intended.

‘I don’t.’

She refused to look at him until he reached over and turned her head gently with his fingertips.

‘I just want to do right by you, Evie, that’s all.’

‘Then stop treating me like I’m made of glass. I won’t break if you touch me. Properly I mean, instead of all this careful patting and stroking. Why do you have to be such a gentleman all the time?’

He kissed her hand and laughed as she rolled her eyes. ‘Why you want to rush everything?’ She kept her mouth shut, forcing him to go on. ‘I just don’t want you to think that I’m only interested in one thing. I messed up before, I know that. I don’t want to lose you again.’ He paused for a moment. ‘I love you, all right? And if we’re going to be together for the rest of our lives then why do we need to hurry?’

‘You love me?’ Her first reaction was to smile, then to laugh. ‘I love you too.’

‘You do?’ Now he was all smiles, leaning forward to kiss her.

There was enough light from next door to see Lawrie’s eyes blacken as he came closer, the hand on her back pulling her into his body as his left hand slipped between the unbuttoned lapels of her wool coat. She opened her mouth to his as his palm brushed against her breast and she began to feel a little light-headed.

Was it wrong to want this? She knew what her mother would say: that she should know better, amongst other choice phrases. But Lawrie was different from other young men; different to anyone else she’d met. He wouldn’t do anything she didn’t want him to. He had asked permission to hold her hand the first time, for goodness’ sake.

The front door banged suddenly, breaking them apart, Lawrie on his feet in seconds. Evie smiled as she watched him leap in one clean motion, his arms pushing him up easily as he vaulted the wall. He allowed a second’s pause as he reached the summit and blew her a kiss. Then he was gone and she heard the creak of Mrs Ryan’s kitchen door as it opened then closed.

‘You been smoking again?’

Evie had to catch herself from falling backwards as her mother whipped the back door open.

‘Sorry, Ma.’ She picked up the butt and stood to throw it in the bin.

‘You will be when you catch a cold. You shouldn’t be sitting out there in this weather.’

A solid woman, thick through the middle and short enough to be called stout, Ma was the very definition of no nonsense. She never bothered with make-up these days and always sniffed whenever Evie wore a little herself, though she did hold her tongue now that Evie was bringing in her own wages. Ma had never married, which was Evie’s fault. She called herself Mrs Coleridge to avoid receiving that look that people, especially women, liked to give her. Of course, once they found out about Evie she did still get that look, but there was nothing to be done about that. Back in their Camberwell days, when she occasionally stepped out with a chap who hadn’t yet found out about her daughter, Agnes Coleridge’s hair had been her crowning glory, thick and curly. Now she kept a shorter, more practical hairstyle, the locks falling no further than her second chin, the ebony losing its battle with the salt.

‘I take it Lawrie was round?’ Ma filled the kettle from the tap.

Evie stared at her mother’s back, not sure if she was in trouble or not. ‘Is that all right? We were only talking.’

‘I do remember what it’s like to be young, you know, and I wasn’t born yesterday. He’s not quite as quick as he thinks he is when it comes to jumping that wall. And you should take a look in the mirror.’ Her mother raised her hand to her chin.

Evie mimicked her action, her cheeks flushing as she felt the irritated skin. Damn Lawrie for not shaving. ‘Sorry, Ma,’ she confessed.

‘I’m sure you know better than to do anything foolish. Nóirín next door seems to think he’s a sensible chap. Got his head screwed on right.’

‘He wouldn’t take advantage if that’s what you mean,’ Evie confirmed. ‘In fact,’ she said, taking a deep fortifying breath, ‘I was wondering if you minded me going to see him play in his band tomorrow night. At the Lyceum. There’ll be lots of people there, and Delia. She’ll be my chaperone, if you like.’

Her mother snorted a laugh. ‘If I was going to choose a chaperone for you then Delia Marson would be at the bottom of that list.’

‘Please, Ma?’

‘Do what you want. You’re old enough. For pity’s sake, Evie, take some responsibility for yourself, won’t you, you’re a grown woman.’

‘Yes. Fine then, so that’s where I’ll be tomorrow night.’

‘Good. Well, since you’ve nothing better to do you can help put away those dishes and then bring me a cup of tea. I’m off to put my feet up.’

Some things didn’t change.

The Friday morning papers shouted of the macabre discovery in the pond, their articles more floridly written now that their intrepid journalists had had time to pry information from the local community – including Gladys Barnett, whose dog had made the initial find. Evie checked three different newspapers on her way to work but she was relieved to find that they hadn’t printed Lawrie’s name.

They had given the baby a name: Ophelia. It was mentioned in more than one paper, as if there’d been a committee meeting held between all the journalists the night before and this was what had been agreed upon. The girl in the pond; the body in the rushes. Only it sounded wrong to Evie’s ears. They must have taken the name from Millais’ work. She’d seen the painting on a school outing to the Tate Gallery, but Hamlet’s Ophelia had been a grown woman, making a choice. This was an innocent baby.

‘You gonna pay for one of them?’ The newsagent had spied her. She chose one at random and handed over the coins.

She was just on time for work, slipping off her coat and hanging it up quickly before grabbing her notepad and pencil and following Delia downstairs. Every morning they headed to the floor below to receive any special instructions from Mrs Jones, their supervisor.

They joined the other partners’ secretaries at the back of the room, Evie noticing more than one of the typing pool girls look her way, whispering amongst themselves. They were talking about the baby – ‘pond’, ‘Clapham Common’, ‘murder’. Did they know more than the papers had printed? Maybe the rumours had begun regardless. What would they be saying once they knew that Lawrie had found the baby? She’d have to tell Delia when they got back up to their own office, safe from the malicious gossipers.

‘I don’t know why anyone’s surprised,’ Mildred said, raising her voice. There was no doubting the target of her attack, not when she was looking right at Evie. ‘My dad says this country’s going to the dogs. If we let in all sorts then we’ve got to expect that things change, and not for the better.’

‘You seem to know a lot about it, Mildred.’ Evie’s voice came out weak and she cleared her throat. Mildred must have been letting her views known before she’d arrived; that was why those girls were staring at her like that.

‘I went to the church service last night and the woman who found her was there.’ Mildred’s face shone with glee. ‘She was telling everyone that they’d arrested one of you lot. A darkie.’

Evie opened her mouth but she didn’t know what she could say without giving Lawrie away. She gripped the edge of the table behind her as her body weakened, panic taking over.

‘So what?’ Delia butted in. ‘They’d’ve questioned anyone who was there, whether they did it or not. It might not have anything to do with him.’

‘Girls!’ Mrs Jones marched in and everyone turned to face the front. ‘Some hush, please.’

Delia put a hand on Evie’s, squeezing it briefly.

Extract from the Evening Standard – Friday 17th March 1950

GRUESOME DISCOVERY ON CLAPHAM COMMON AS BABY FOUND DEAD

More details have emerged regarding the body of a baby that was found yesterday, hidden in the shallows of Eagle Pond, Clapham Common.

The discovery was made by a local woman, whilst walking her dog in the vicinity of the pond. Police have confirmed that the woman is unrelated to the case, and that they are already questioning a person of interest, a man who was discovered close to the scene.

The child has yet to be identified but we are able to disclose that the baby was female, 10-12 months old, and well cared for. It is still unknown whether her death was a consequence of foul play or accident. She was found wrapped in a white woollen blanket with a floral decoration so it is likely that she had a mother who cared for her.

Police ask that anyone who has any information call in at their local police station as soon as possible. If anyone knows of a baby of the right age who hasn’t been seen in a while, or was in the area on the evening of Wednesday 15th March, or the early hours of Thursday 16th, please think carefully – you may have seen something which at the time seemed unimportant but may be vital to the police investigation.

There will be special prayers said for the deceased at both St Mary’s and St Barnabas’s churches again this evening for local parishioners who wish to pay their respects following a generous turn-out yesterday.

5

There were far better ways of spending a Friday evening than waiting on a cold station platform for an unreliable friend. But here he was, freezing his arse off at Waterloo as legions of buttoned-up office workers marched past him on their way home to the suburbs. They all looked the same: harassed and hunched over, their grey overcoats and hats giving the appearance of a national uniform. The shoes were the only clue; the most reliable way to tell boss from employee, the tenant from the landlord. Lawrie’s own dress shoes were polished to a high shine but the soles were not original and the leather was cracked along the throat line.

Aston had rung him up on the telephone on Tuesday. A lifetime ago, it felt like. Few more days and I’m a free man! Thing is, I need somewhere to stay… And how could Lawrie say no? Aston had served in the RAF since 1942, side by side with Lawrie’s brother until that last fatal mission, just weeks before the war ended. But of course, Aston was late. He hadn’t been on the train he should have been on which meant that he’d missed it, probably ’cause he’d got chatting to some pretty girl on his way to the station, and they’d both have to wait for the next. As usual. Lawrie checked his watch; he still had time.

He felt a debt to Aston, not least because it was one of Aston’s RAF contacts who had finally managed to get Lawrie his Post Office job. It had been Aston who had come down to Kingston two years earlier and talked Lawrie on to that boat, convinced Mrs Matthews that it was a wise idea to send her remaining son overseas where he could seek his fortune. She’d cried as she waved her surviving son off but she had a new husband to look after her now. Lawrie had only been in the way, Mr Herbert from the grocery store leaping at the chance to comfort the handsome widow as she grieved for her eldest son. How well it all worked out in the end, the new Mrs Herbert wrote to her son months later, taking his good news missives at their word.