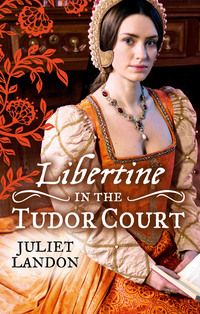

LIBERTINE in the Tudor Court

But before Adorna could comply, the curtain rattled to one side to reveal an unknown figure who stood swaying on the threshold, his face bloated and purple with drink, his eyes swivelling from one female figure to the other. ‘Eh?’ he said, thickly. ‘Two…two of you?’ He swept a hand over his face. ‘Can’t be. I’m seeing things again.’ He kept hold of the curtain for support while he fell into the cubicle with an outstretched hand ready to grab at Adorna’s bodice.

She lashed out, yanking at the man’s hair as he came within range while Seton, in the confined space, picked up the jug of ale to hit him over the head. The curtain and its flimsy pole came down with a splintering crash as the intruder was yanked firmly backwards by a dark green arm across his throat and, above the mesh of curtain and limbs, Adorna identified the green-and-red-paned breeches of Sir Nicholas. Standing astride the prostrate drunkard, his eyes switched from brother to sister and back again, his expression less than sympathetic.

‘Congratulations on your performance, Master Pickering. Are you hurt, mistress?’ he said to Adorna.

There had not been time for any injury except to her composure, which had suffered even before her meeting with Seton. ‘No, I’m not hurt, I thank you,’ she said. Curious faces had appeared behind Sir Nicholas, and a pair of stage-hands came to drag the man away by his feet, still parcelled. The curtain rail lay smashed across the passageway. ‘Who was he, Seton?’ she asked.

‘The usual kind of backstage caller with his congratulations. It’s quite a common occurrence, love.’

‘You mean they come here to…?’

Seton smiled and pulled off his wig, making himself look, in one swift movement, utterly bizarre. ‘Yes, all part of the business. You have to get the wig off first. That usually stops ’em.’ He took Adorna’s hand. ‘Now you must go. Let Sir Nicholas take you home. He appears to be more security-conscious than your Master Fowler. Sir…’ he turned to Sir Nicholas ‘…we were glad to have your assistance. I thank you. Could you see my sister safely home, please? She should never have been allowed to come backstage on her own.’ His voice wavered over an octave.

‘Your sister didn’t come here alone, Master Pickering. I was waiting at the other end of the passage for her. And you may rest assured, I intend to see that she gets home safely.’

On that issue, there seemed no more for Adorna to say except to hug Seton once again and assure him that she would give good reports of the play to their parents. Outside, however, in the emptying space of the shadowy theatre, she began her objections, suddenly realising how impossible it would be to follow Maybelle’s advice at a time like this. ‘Sir Nicholas,’ she said, slowing down, ‘I came with Master Fowler and Cousin Hester and our servants. We shall be quite safe enough, I assure you. I thank you, but—’

‘No need to thank me, mistress,’ he said, coldly formal with his use of her title. ‘You will be going home with Master Fowler, as you came. But I told your brother I would give you my personal protection, and that is what you’ll get, whether you want it or not.’

She stopped in her tracks. ‘You came here, sir, with your own friends and I came with mine. I prefer not to join you.’

Unmoved, he stopped ahead of her with a loud sigh, only half-turning to explain as if to a difficult child. ‘You are not joining me,’ he said, wearily. ‘I’m joining you. My friends have gone home. They are Londoners. Now, can we proceed? The horses will be getting restive and your cousin Hester will be worrying, I expect.’ Whether about Adorna or the horses he did not specify.

She could not explain why she preferred Peter’s company to his, nor why she felt embarrassed that he had seen her brother at less than his best and unable to shield her from harm, the way he had done. The afternoon had not lived up to her expectations, and her heart bled for Seton, whose discomforts had been far more acute than any of theirs.

Rather like the play itself, the journey home was long, uncomfortably hot, and tense with an act which, as far as some of the characters were concerned, made them relieved to reach the end. Whether she would admit it to herself or not, she had been further nettled by this latest display of Sir Nicholas in the company of women, though the thought no more than skirted the labyrinth of her mind that there was no good reason why he should not be at a playhouse with friends of either sex. New to jealousy, she still did not recognise its insidious tentacles.

Just as bad was the small howling voice of reason that reminded her, at every glance, of the prejudice he had pleaded with her not to hold. A dozen times on that journey from London to Richmond, she watched him and listened to his deep voice as he talked easily with both Peter and Hester, and she wondered whether this unpredictable return to his original abruptness signalled an end to his efforts to win her interest and, if it did, then why had he followed her when she went to see Seton? She recalled her father’s persistence, his four times of asking, and wondered how her mother’s nerves had stood up to the uncertainty.

On reflection, it could only have been by design that, as they entered the courtyard of Sheen House in the early evening, Sir Nicholas manoeuvred his horse near enough to hers for him to be the one to lift her down from the saddle, leaving Peter to assist Hester. As her feet touched the ground, she would have removed her hands from his shoulders as quickly as she could, but he caught them tightly and held her back, unsmiling.

After miles of contemplation, Adorna would have pulled away, angrily, her hurts being multiple and confused and not to be easily soothed. Certainly not in the temporary shelter of her horse in a crowded courtyard. But she was surprised enough to wait as he touched both her knuckles with his lips, sending her at the same time the quickest whispered message she had ever heard. ‘At bedtime. In the banqueting house.’ Then he released her, turning away so fast that she might even have imagined it.

Her first reaction was of an overwhelming relief that, like her father, he had not given up too soon. Hard on its heels came the heady thrill of fear and promise; already she could feel his arms, his mouth on hers. Then, what if she refused to meet him, to show him once and for all that she had no intention of being added to his list, whether at the bottom or the top? How that would teach him a lesson more swiftly than Maybelle’s version, though it would leave her longing for something she had tasted and would never taste again? Was she experienced enough to deal with that?

As she had half-expected, Peter and Sir Nicholas were both invited to supper and, since it was already an hour later than suppertime, they readily accepted. Hester, exhausted by the three-day effort of being sociable, left the conversation to the others and retired to her bed soon after the meal. Adorna, however, was compelled by the circumstances and by her own confusion to maintain a pretence of indifference towards Sir Nicholas, which, she believed, would give him no hope that she would accept his invitation. At times she came close to being sure that she would never do so, for that would be to walk into his trap like a drugged hare. Her resolution veered by the hour.

Peter and Sir Nicholas took their leave of the Pickerings together, the duties of Her Majesty’s Chamber coming before pleasure and, whether for friendship or to make sure of the competition, Sir Nicholas rode with him back to the palace, presumably to return later, unseen.

‘I do wish you would try to unbend to Sir Nicholas a little, Adorna,’ Sir Thomas said as they watched the guests depart. ‘He’s a most pleasing and competent chap. Knows his job, too, by all accounts.’

‘You’ve been making enquiries, Father?’

‘Yes,’ he said, taking her arm. ‘Of course I have. He’s Lord Elyot’s son and he’s gleaned most of his horse skills from Samuel Manning, Hester’s uncle. Good connections.’

‘And what about his connections with Lord Traverson, Father? Do you know anything of those?’

‘Traverson? No, nothing at all. All I know about Traverson, the old fool, is that he’s sent his eldest daughter off to Spain to marry some duke or other. That’s as near to being a royal as he’ll ever get, for all his efforts. What do you know about him, then?’

‘Nothing at all, except that he’s one of the Roman Catholics that Her Majesty objects to.’

‘So that’s why he’s sent his wife and daughters off to Spain, I expect, to get them to safety. No Protestant would risk the Queen’s anger by taking the daughters on, her views being what they are, and nor would Traverson allow it, either. So much for religious tolerance. Come on in, love. Time for bed. You’ve had a busy day.’

‘Yes, Father. I’ll go and lock up the banqueting house.’

‘Eh?’ he frowned. ‘Lock up the—?’

His arm was caught, quite firmly, by his wife’s hand; she pulled him back and closed his mouth at the same time.

Chapter Five

R eciting her opening lines, Adorna opened the door and went inside, sure in the pit of her stomach that this was not a sensible thing to do, and certainly not the way to show a man how consistently unaffected she could be. It was not so much that a well-bred young woman would not have done this kind of thing; she would, there being few enough places where one could be private, let alone with a lover. Every nook and cranny had to be made use of. But having acted the hard-to-get with such force, this would seem to him like a remarkably sudden capitulation after so little effort on his part. Even her mother had put up more resistance than this, apparently.

On the other hand, the invitation may have been no more than a cruel jest. The thought sent shivers of fear across her like an icy draught.

The place had been swept and tidied with the sun’s warmth still locked inside, the first deep shadows of night clothing the painted walls and blackening the windows. She waited, straining her ears towards every sound, picking up the distant hoot of an owl and wondering vaguely how she could be at such odds with herself that she could do the exact opposite of what she had planned to do. Could she be in love against her will? Was that what love did?

From the palace courtyard a clock chimed the hour, then the half-hour. She sat, stood, and sat again, starting at every sound, watching the lights go down in the house, one by one. Another hour chimed. Numb with anger and cold, she closed the doors behind her, quietly, this time. One last look towards the wall where the door led from the paradise into the palace garden, then she picked up her skirts and went into the house with a painful knot burning in her throat, knowing that this must be the snub she had predicted, though not quite so soon. That, and the coolness since his appearance at the theatre, would be his way of teaching her that it was he who had the upper hand.

There was one thing, however, that this fiasco had taught her; that she would never be caught like this again, that it had mercifully prevented her from continuing from where they left off and that, in effect, she had had a narrow escape. She should be thankful. This time, she would not weep or admit that her pride had taken a fall. She could act, as Maybelle had reminded her. Let them see how well she could perform.

Yet in her dark bed, the act was abandoned and the mask of nonchalance removed, and she gave way to the surge of uncontrollable longing that his kisses had awakened in her. After that, she fumed with anger at the man’s arrogance, his sureness that she would come willingly to his hand. Never again. Never! She would die rather than become one of his discarded lovers.

The timing of it could not have been better even if Dr John Dee, the Queen’s astrologer, had looked into his scrying-glass and forecast the best day for forgetting, this being the day of the masque in the royal palace for which she and her father’s men had put in weeks of preparation. To have every prop ready on time, they would have to work nonstop.

Hester went with Adorna to the Revels Office, insisting that, although neither of them would be taking part in the masque, she could assist with the embroidery. ‘Is this the bodice?’ she whispered to Adorna, her eyes widening at a mere handful of tissue. ‘This bit here?’

‘Yes, that’s it.’ Adorna smiled. ‘Many of the Court ladies show their breasts nowadays at this kind of event. This is modest compared to some.’

‘You designed it?’

‘Yes, four like this and four with a silk lining. This one’s for Lady Mary Allsop. She likes to be seen.’

‘But you can see through it!’ Hester didn’t know whether to laugh or to appear shocked. ‘What does Her Majesty say to this?’

‘Her Majesty is very careful not to let anyone outshine her,’ Adorna whispered, laughing. ‘She bares almost as much herself, occasionally.’

Only a few days ago, the idea of Cousin Hester sewing spangles on semi-transparent masque-costumes for ladies of the Court would have been unthinkable. But there she was, beavering away with her shining brown head bent over a heap of sparkling sea-green sarcenet at five shillings the yard, actually enjoying the experience. Even the apparent contradiction of women taking part in a masque while not being allowed to act on stage had been accepted by Hester without question. Adorna had also noticed how the men made any small excuse to attract Hester’s attention and how she was now able to speak to an occasional stranger without blushing. Cousin Hester was taking them all by surprise.

Sir Thomas smiled at his daughter, lifting an eyebrow knowingly.

By evening his smiles had become strained as he supervised the magnificent costumes being packed into crates for their short journey across several courtyards to the Royal Apartments at the front of the palace, along corridors, up stairs, through antechambers and into a far-too-small tiring-chamber. As the one who knew how the costumes were to be fitted, Adorna went with them to assist the tiring-women amidst a jostle of bodies, clothes, maids, yapping pets, crates and wig-stands.

‘Here’s the wig-box, Belle,’ Adorna called above the din. ‘Keep that safe, for heaven’s sake.’ The wigs were precious golden affairs of long silken tresses weighing over two pounds each, obligatory for female masquers.

She checked her lists, ticking off each item as it was passed to the wearer’s maid, waiting with suppressed impatience for the inevitable late arrival. ‘Where’s Lady Mary?’ she asked one of the ladies.

The woman wriggled out of her whalebone bodice with some regret. ‘Don’t know how I’ll stay together now,’ she giggled, happy with her pun. ‘Lady Mary? She wasn’t feeling well earlier, mistress. Anne!’ she called to the back of the room. ‘Anne! Where’s Mary?’

‘Which Mary?’ came the muffled reply.

‘Mary Allsop!’

‘Not coming. Indisposed.’

Adorna’s heart sank. ‘What?’ she said. ‘She can’t—’

‘Indisposed my foot,’ the courtier simpered. ‘I expect she’s chickened out at the last minute.’ She glanced at the costume Adorna held.

‘As usual,’ someone else chimed in.

‘But we can’t have seven,’ Adorna said. ‘There have to be eight Water Maidens in four pairs. There are eight men expecting to partner you.’

The courtier held her breasts while her maid pulled a silky kirtle upwards to cover her nakedness, fastening it at the waist. ‘This is like wearing a cobweb,’ she grinned. ‘Well then, Mistress Pickering, you’ll have to take her part. You’ll fit that thing better than anyone, I imagine.’

Adorna was not going to imagine any such thing. ‘Er…no. Look, one of your maids can do it. Now, who is the nearest in height to…?’

There was a sudden surge of protest as Adorna’s suggestion was rejected out of hand. ‘Oh, no! Not a maid. No, mistress.’

‘The masquers must be from noble families.’

‘Or Her Majesty would be insulted, in her own Court.’

‘Adorna, come on, you can do it.’

‘Yes, you’re the obvious stand-in, and you won’t need to wear the wig, either. Come on, mistress.’

‘I cannot. I’ve never worn…well…no, I can’t!’ Even as she refused she knew the battle to be lost, that there had to be eight and that she would have to take the place of the inconsiderate absconder. At the same time, she could still remember what pleasure she had derived from designing each costume which, although slightly different in colour, style and decoration, had made up the eight Water Maidens. She had imagined herself wearing each costume, floating in a semi-transparent froth that swirled like water a few daring inches above the ankle. She had tried some of them on when only herself and Maybelle had seen, sure that no one would ever see as much of her as they would of the Queen’s ladies.

The masks had been adjusted to hide the wearers’ identities from all but the most astute observer. No one would know it was her except, perhaps, by her hair.

‘Wear the wig,’ said Maybelle, ‘then they’ll not know till later that you’re not Lady Mary.’

But Adorna knew how unbearably hot the wigs were. ‘Not if I can avoid it,’ she said. ‘I’ll risk my own hair. I’m only one of eight, after all.’

‘Then you’ll do it?’

‘I think I’ll have to, Belle. But…oh, no!’

‘What?’

‘This is the one with the…oh, lord! What would Cousin Hester say?’

‘She’s not going to know unless someone tells her. It’s what Sir Nicholas will say that’s more interesting,’ she said, cheekily. ‘Think of that, mistress. This’ll show him what he’s missed better than anything could.’

‘I had thought of that, Belle.’

‘Well then, step out of this lot. Stand still and let me undo you.’ She spoke with a mouthful of pins as she detached the sleeves, bodice and skirts while Adorna still ticked off her list and handed out silver kid slippers, silk stockings, tridents and masks to the ladies’ maids.

There was only the smallest mirror available for her to see the effect of her disguise as it was assembled, piece by piece, upon her slender figure. But both maid and mistress noticed the women’s admiration as the silver-blue tissue was girdled beneath her breasts, neither fully exposing nor hiding the perfect roundness that strained against the fabric at each movement. Others were more daringly exposed, but not one was more beautiful than Adorna, so Maybelle told her as she placed the silver mask over her face and teased the pale hair over her shoulders.

‘There now,’ Maybelle said, placing the papier-mâché conch-shell on Adorna’s head. ‘It’ll take ’em a while to recognise you in that.’ Not for a moment did she believe her words, for there was dancing to be got through before the masquers could be revealed, and Adorna’s shimmering pale gold waves were far lovelier than the wigs.

‘So this,’ Adorna muttered, ‘is what Seton means by stage fright.’

With the last checks in place and the head-dresses imposing an unnatural silence upon the eight Water Maidens, they waited for the trumpet-call to herald the entry of the masquers. Then the door was opened, assailing them at once with a blaze of light and jewels, colourful and glittering clothes, eager faces and the dying hum of laughter. Blinkered by the small openings in the masks, they saw little except the immediate foreground, but now Adorna realised how this hid their blushes as well as so many leering eyes that strained to examine every detail.

Surrounded by her favourite courtiers, tall and handsome men, the Queen was seated on a large cushioned chair at the far end of the imposingly decorated chamber that glowed warmly with tapestries from ceiling to floor. The latter, clear of rushes, had been polished for dancing and now reflected the colours like a lake through which the eight glamorous masquers glided in pairs, each pair led by a semi-naked child torch-bearer with wings.

One child, mounted on a wheeled seahorse, asked the Queen to approve of the masque, but Adorna’s eyes had rarely been so busy in trying to seek out, without moving her head, someone she recognised. Her father would be otherwise engaged with the props behind the scenes, the organisation and mechanics of the clouds, the little Water Droplets, the noise of the thunder and the giant sun’s face that smiled and winked. While she paraded and danced a graceful pavane she could not help wondering what he would say when he knew.

The doubt about his approval nagged at her, blunting the pleasure of seeing Sir Nicholas’s reaction to what she intended to deny him. The pleasure waned even further as she became quite certain that Sir Nicholas was not present. Some of the other masquers were having no such qualms, for they had already made some minor adjustments to reveal more than had originally been intended, but it was after the pavane that a shriek and a sudden parting of the crowd indicated that there had been an invasion of sorts. A group of tall silver-clad men, glittering in satin-beaded doublets and silver-paned breeches, strode fiercely through the open door, yelling and whirling white fishing-nets about their half-masked heads.

‘Ho-ho!’ they called. ‘What treasures do these fair Water Maidens bring? Yield them up, Maidens! Yield up, we say!’

This was the part of the masque about which Adorna had been kept in the dark, being concerned only with the women’s department, but now she recognised at a glance both the Earl of Leicester and Sir Christopher Hatton by the shape and colour of their beards. They threw their nets about with gusto, making the women guests yelp with excitement, but it was the Water Maidens who had to be netted, and it was they who fled furthest.

There were some, naturally, who did not make it too difficult for the fabulously dressed Fishermen with the white ostrich-plumed caps, but Adorna was not one of them, suspecting that Sir Nicholas was probably a Fisherman with his sights on one of the others. This was her perfect chance to be netted by someone else, to let him see, as Maybelle had said, what he was missing.

‘Here, my lady,’ she laughed, removing her conch-shell head-piece and handing it to a courtier old enough to be her mother. ‘You could be netted, if you wish it.’

Willingly, the lady held it above her head, drawing the Fishermen’s attention while Adorna skipped aside to find one of the eight who looked least like Sir Nicholas, a ploy that misfired when, as she dodged Sir Christopher’s net, she whirled round to find that the man she had hoped to evade had spotted her. His wide shoulders, proud bearing and dark hair could not be concealed by the silver half-mask any more than she was by her complete one.

Across the long room they surveyed each other, one with legs apart, menacing and determined, the other equally adamant that any man would be preferable to this one, at this moment. She slipped away to where guests shoaled like fish, but it was too late to mingle with them before his net flew through the air towards her.

She threw up a hand to ward it off, catching it and hurling it aside scornfully, feeling a surge of triumph as she planted both feet firmly on it, glaring at the Fisherman. The guests, unused to anything but a token show of resistance, roared their approval of her clever ruse and turned to watch what would happen next while, at the far end of the room, the Queen’s head appeared above all the others to see what was going on.

Ready to sprint off again at the first hint of approach, Adorna was not prepared for the sudden shift under her feet as Sir Nicholas yanked hard at the net, pulling it on the slippery floor to unbalance her and bring her down on to her side with a sharp slap. Then, laughing softly, he hauled his net back and shook it out unhurriedly, his voice challenging and strong. ‘Come on, Water Maiden!’ he called. ‘You should be as used to this performance as I am by now. Come, let’s have a look at your bounty, eh?’

The men yelled and clapped, but Adorna’s expression was well hidden behind her mask, though her voice betrayed enough to suggest that this was not all an act. ‘I’m a cloud, Sir Fisherman! A mist. A waterfall. I have no fish, no bounty. You’ll get nothing from me. Go and seek your bounty elsewhere.’ Quickly, she scrambled to her feet, vexed that her flimsy bodice had not been designed for this kind of activity and that her legs, usually concealed, were now perfectly outlined for all to see. Hoping once more to hide in the arms of the guests, she turned towards them. But they were far too occupied in cheering her bravado and in ogling her charms to move aside and, before she could think of an alternative, the net came swinging towards her once more to fall neatly over her head and shoulders.