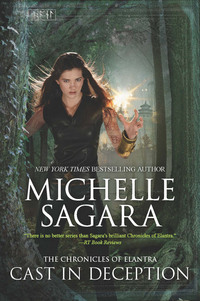

Cast In Deception

“Yes.” As she spoke, some of that color shifted, becoming less of a flat, moving splash against stone as it did. Kaylin was suddenly reminded of Annarion in Castle Nightshade and was glad that she hadn’t bothered to eat much.

“Guys,” she said, raising her voice to be heard. There wasn’t much sound in the room if she stopped to think about it, but something about the kaleidoscope of color implied shrieking. “There is no way you are going to the High Halls like this! There’s no way you could even enter a Hallionne in this shape or form!”

The slowest of the racing colors recombined; they came together in a way that resembled Annarion, had he been sculpted by someone who wanted to suggest his form artistically, rather than render it realistically. Even his eyes—which were very blue—did not look solid or whole.

“Your brother is coming to visit,” she told him. “And I’d really appreciate it if you’d give Teela back—Tain is about to explode.”

* * *

It took another five minutes before Annarion resembled his usual, breakfast-room self. Teela emerged more quickly, but her color was off. Kaylin would have been gray or green; Teela was simply pale. Her eyes were the same shade of midnight that Annarion’s were. Mandoran did not coalesce.

Tain was at Teela’s side the minute her feet were solid—and it was her feet that took shape last. In all, it was disturbing; it was not something that Kaylin had seen Teela do before, and she had a very strong desire never to see it again.

“Look, I appreciate that you guys had to learn how to talk to, and live in, a Hallionne. But Teela didn’t and she is not cut out for this. You’re guests here. I’m happy to have you. Mostly. But this has got to stop.”

Mandoran lacked a mouth to reply.

“No, he doesn’t, dear, but I don’t think I’ll repeat his answer.”

Kaylin folded her arms. To Annarion she said, “Your brother will be here soon. Anything you can do to become more solid would probably be good.”

“Oh great,” Mandoran said, speaking for the first time. “Tell him we don’t want visitors.”

Kaylin’s arms tightened. “If this is what you do when you’re upset or worried, you’re never going to become Lords of the High Court. I doubt they can actually kill you—but they can make you all outcaste if you push it.”

Bellusdeo dropped a hand on Kaylin’s left shoulder. Small and squawky curled his tail around her neck. He didn’t lift a wing to bat her face, and he didn’t press it over her eyes, either. If he could see Mandoran as he was, he didn’t feel it was necessary for Kaylin to see him, too.

“If you’re all outcaste, you’ll never take that Test. You won’t make it past the front doors.”

“They can try to stop us.” Mandoran’s disembodied voice again. The splashes of flat color across the room’s walls moved as he spoke. It was not comforting.

“Kaylin,” Helen began.

“They will try. But you’re not the people they’ll put pressure on first. Maybe you’ve got no friends and no living family. Maybe you’ve got family, and they don’t want to give your stuff back. But Teela has friends. She has allies. They’ll start there first, because they don’t have a choice. They’ve already started.

“Teela may be part of your cohort, but she’s lived in the High Halls for centuries, on and off. She’s the wedge in the door. She went to the green, and she returned. She fought Dragons. She did it well enough that she has one of the three damn swords.

“If they can kill her, they’re free to shut you all out.”

Tain cleared his throat. Teela locked her hands behind her back, which was unusual. She really did look terrible.

“This is the only place you can afford to do this—and it’s hard on Helen. If you could please pull yourself together, we can have the rest of this discussion.”

“What rest?” Mandoran demanded, not really budging. Or not really staying still; the colors were practically vibrating.

“Your cohort,” Kaylin snapped back.

The rest of the colors bled from the walls back into the center of the room, as if they were liquid and someone had just pulled a plug. Mandoran stood three feet from Annarion, his arms folded in almost exactly the same way Kaylin’s were. His expression was grim, his eyes narrowed slits. “...Fine,” he said. “I’m listening.”

It was Teela who turned to Kaylin. “We are not in contact with our...cohort, as you call them. Helen says the lack of communication is not by her choice; she doesn’t interfere with us.”

“I contain the unintentional noise,” Helen added.

“You can stop communication between people who are bound by True Names,” Kaylin pointed out, more for Teela’s benefit than Helen’s, since Helen already knew this.

“Yes. But again, I do not interfere with the cohort in that fashion. I interfere—on occasion—on your behalf. You are not entirely guarded, and I believe there is some information that you have deliberately chosen not to divulge. I merely maintain some privacy of thought while you are within my boundaries. Teela is capable of doing so on her own.”

“I notice you haven’t mentioned Mandoran or Annarion.”

There was a small pause. “They are not, as you imagine, terribly private in their communications with their cohort. I don’t think they’re capable of it, but it is not necessary. For all intents and purposes, all of the cohort except Teela are like a much smaller Tha’alaan.”

The Tha’alaan was not small. It was a living repository of the thoughts of an entire race, dating back—if dating was the right word—to its creation.

“So...the cohort sent one message and they’re gone?”

“Yes.”

“Are they still alive?”

Mandoran was looking slightly stretched. Annarion, however, was looking entirely like his usual self.

Again, it was Teela who answered. “Yes. If Nightshade died, you would know. We know they are still alive. But that’s all we know.” She let the silence stretch again before she said, “I’ve lived most of my life without contact with my cohort.”

“But...you knew they were alive.”

“I knew they were not dead. But I knew, as well, that they were beyond my reach. I could not hear them. They could not hear me. I assume this was the Hallionne’s decision, but have never asked. I am not Tha’alani. I am Barrani. My life, my existence and my sanity are not predicated on my connection to the thoughts of others. There is a natural expectation of silence.

“Annarion and Mandoran don’t have that. The centuries I spent in the natural silence of my interior thoughts, they spent in constant communication.” She hesitated, glanced at Annarion and Mandoran, and then continued. “I am not sure they would have remained sane, otherwise. Terrano was the most...adventurous...of all of us. I haven’t heard his thoughts since their return to us—but neither have they.”

Terrano was the lone member of that long ago cohort who had had no desire to return to his kin. He had not reclaimed the name that had been his from just after his birth, and the names themselves were the binding that held the cohort together.

“Are you afraid that he came back for them?”

Mandoran snorted. “No. Look, he wanted—for us—what we wanted for ourselves. And we wanted, for him, what he wanted for himself. There’s no way he would come back, attack them, and carry them off. There’s a small chance that he approached them and attempted to convince them they’d be happier where he is now—but the rest of us would know.”

“Fine. What did they see?”

Silence.

“Teela?” When Teela failed to answer, Kaylin turned to her House, figuratively speaking. “Helen.” Her voice was flat; there was no wheedling in it. “What did the boys see?”

“They have been trying,” Helen replied, “to describe it.”

“They can’t. You can.”

“I can describe it to them, yes. It is not a matter of privacy, Kaylin. It is a matter of words, of experience. Something happened. The cohort have been learning from Mandoran and Annarion. They have been practicing to live outside of the Hallionne. But they have had less practice and less contact with people like you. The closest analogue is Teela, but it is hard for them to think like Teela, because to do so, they have to experience only a narrow range of their existence.

“It is like trying to pour the contents of a pitcher into one glass. For you, it is natural; you understand how quickly water flows. You understand when to stop pouring. They are attempting to do what you naturally do when they can see neither the pitcher nor the glass.”

Kaylin turned to Mandoran. She poked her familiar. Her familiar squawked and squawked again, like an angry bird.

“It is not that you would not see what happened were you there,” Helen said, after a pause. “You would. But you would not see it as they saw it. You would not understand it as they might.”

“If I try to stab Mandoran right now and you don’t attempt to stop me, he’s going to see it the way I see it.”

“Yes.”

It was Annarion who said, “No.”

“Did someone try to stab them?”

It was Teela who said, “I think so, figuratively speaking.” At Kaylin’s expression, she added, “Just because you can see what someone else is seeing doesn’t mean that it makes more sense. I haven’t had the experiences the rest of my cohort has had. I have had more experience with the arcane arts that are confined to the reality I perceive. I believe, if you were to venture to the location in which they disappeared, you would find obvious—and large—traces of magical aftershocks.

“It is possible that those aftershocks exist for perfectly understandable and harmless reasons—”

“But not bloody likely.”

“Not in my opinion, no.”

Kaylin opened her mouth. Before words came out, Helen said, “I believe Lord Nightshade has arrived.”

Annarion said nothing. Mandoran, however, said a lot. In Leontine.

* * *

By this time, everyone was more or less “stable” as Helen called it, and she ushered them all into the parlor. Kaylin would have preferred the dining room, but Helen chose to ignore those preferences, probably because Nightshade was involved.

Moran was not in residence, which was the one silver lining of the evening. The last thing Moran needed was the political infighting of an entirely different caste court, given her current position.

Everyone else, however, was in the parlor. Mandoran had attempted to have Bellusdeo excluded, but Helen vetoed it, and Kaylin—who really didn’t want to put the Dragon at risk—hadn’t the heart to agree with Mandoran. Bellusdeo was more likely to survive extreme danger than Kaylin herself.

Nightshade appeared composed and almost casual. He also looked like he’d gotten sleep. While she knew the Barrani didn’t require sleep, every other Barrani in the room, Tain included, looked like they needed about a week of it. She was certain she didn’t look any better.

“Not really, dear,” Helen said.

Severn was the only regular who wasn’t in attendance.

Annarion’s bow, when offered to his brother, was stiff and overly formal, which was not lost on Nightshade. Since the brothers had had almost two weeks of relative peace, Kaylin had hoped that this meant arguments were behind them. But no, of course not. The issues that had caused the argument hadn’t been resolved.

The attempt, on Annarion’s part, to resolve them had become the point of contention, widening the conflict to encompass everyone else.

Helen offered drinks to everyone present. Teela and Tain immediately accepted. They didn’t ask for water. Kaylin, who already had a headache, decided that alcohol wasn’t going to make it any better, but Mandoran followed the Barrani Hawks’ lead. Annarion and Nightshade did not.

“Kaylin has told me some of what has occurred.”

This wasn’t entirely accurate, but Kaylin let it go. What mattered right at this particular moment was the cohort. All of it.

Annarion was silent. Teela, however, took the reins of the conversation, such as it was. She had always been a reckless driver—no one with any experience in the Hawks let her drive anything if they had to be a passenger—but she steered this particular conversation with ease. Probably because it was short and the Barrani were good at implying things without actually using the words.

“But they were not in the Hallionne?” Nightshade asked, when it was clear Teela had finished.

Mandoran answered. “No. They were in transit to Hallionne Orbaranne, on the portal paths.”

Annarion did not glance at his brother, but it wasn’t required. Kaylin suspected it was Annarion who was directing the conversation because Mandoran spoke High Barrani, and he spoke it politely and perfectly.

Nightshade considered them all. “Lord Bellusdeo,” he finally said.

She was orange-eyed and regal as she nodded. Teela’s eyes were blue; Tain’s eyes were blue. They were seldom any other color in the presence of Nightshade.

“Lord Kaylin has been granted access to the Hallionne, should she be the agent of investigation. You however...”

“Have not.”

“No.”

“And would not likely be granted that access.”

“No. The Hallionne are not duplicitous, in general; they would not offer you rest or shelter with the sole intent of destroying you once you were entirely within their power. At best, they would become a prison, should they be inclined to grant permission they were not built to grant. If, as I suspect, intervention is required, it would be inadvisable for you to travel west.”

“And you, as outcaste, would be granted that permission?”

“I have offered blood to the Hallionne; I have paid the price of entry. Once accepted, the Hallionne will not reject me unless there is deliberate intervention.”

“I do not understand how there could not be.”

“No, you do not. The Dragon outcastes and the Barrani outcastes are not the same. Among your kin, you would have had both friends and enemies, as is the case with the Barrani. But the designation of outcaste has a physical meaning to your kin that it does not have to mine. The Barrani designation is political. It is oft deadly, but not, as you are aware, always.

“If the High Court considered me the danger that Dragon outcastes are considered, they might bespeak the Hallionne—but it is both time-consuming and dangerous to do so. They cannot merely mirror the Hallionne and change the guest list; they must travel in person. And the request is not delivered by the simple expedient of word.”

“The Consort could do it,” Kaylin said.

“Yes. But it is not without cost to her, and the High Lord seldom countenances such an action.”

Kaylin hesitated again. It was marked by everyone in the room, but they were all on high alert. “Your brother’s friends aren’t outcaste.”

“Not in the political sense, no. And they had permission to travel; they gained it during the war and it was not revoked.”

“During the war.”

“When they traveled to the West March at the behest of the High Court.”

“...They’re not the same as they were then.”

“No. They carry, I am told, their names. But they are closer now to Dragon outcastes than Barrani outcastes have ever been. It is tacitly unacknowledged. The Hallionne Alsanis has restricted the flow of information about their time in his care, but he is in contact with the other Hallionne that form the road they will travel. Not until they leave Kariastos, if they travel that far, would they be required to travel across land—and Kariastos is well away from the shadowlands and ruins the Hallionne were built to guard against.”

“Annarion and Mandoran did not travel the portal roads to reach Elantra.”

“We’d spent enough time in the damn Hallionne,” Mandoran said, dropping High Barrani in favor of the Elantran he usually preferred. “We thought it would be a nice change to travel outside of one. Mostly, it was boring. And sullen.”

Annarion’s expression was not nearly as neutral as Teela’s as his brother continued to speak.

“The Hallionne are capable of limiting communication of any kind beyond their borders. You are aware that Helen...oversees our communication to a greater or lesser extent. Helen is not the equal of the Hallionne. If she has that functionality, it would be naive to think the Hallionne do not possess it as well.”

Kaylin struggled with resentment; she didn’t want Nightshade to talk about Helen as if Helen were a thing, an inanimate object.

Helen, however, did not appear to suffer the same resentment. Her gaze went to Kaylin, and one brow rose in curiosity. “He speaks of me,” she said, “as if I were a building. And Kaylin, I am. It is the core of what I am.” She turned once again to Nightshade. “I am not in contact with the Hallionne; I cannot say if his assumption is correct. But I believe it must be.” To Nightshade, she said, “Do you believe that Kaylin will be required to visit the Hallionne?”

“I am uncertain at this point. But I do not believe it would be in the best interests of either Annarion or Mandoran to investigate in person.”

“And Teela?” Kaylin asked.

“Teela has been a guest at the Hallionne after her return from the West March; she has been more, at the behest of the green. The Hallionne will not cage or attempt to destroy her. They know her and they accept her.” He turned to Teela. “I have heard that there has been some difficulty in the Halls of Law.”

She failed to glare at Kaylin, not that it would have made much difference to the color of her eyes. If Helen could limit communication within her boundaries, she had no control of what Nightshade could hear outside of them.

“If it is true that there is some unfortunate political unrest, this may be an appropriate time to investigate.”

“I will take that into consideration,” Teela replied. Her voice, like her expression, was a forbidding wall. Kaylin could well imagine what consideration meant, in this case.

Mandoran cursed in Leontine. Since no one had said anything out loud, Kaylin assumed it was at something that passed privately between the three who could speak without speaking.

“There is nothing you can do tonight,” Helen said, and Kaylin revised that number to four. “Kaylin intends to visit the Consort in person.”

“Oh?” Teela’s word was cool. Chilly.

“Yes, dear. Her initial concern was Candallar. Kaylin is sensitive to the idea of fieflords and their interactions within Elantra.”

Teela exhaled. She did not, however, look any friendlier as she turned her glare on Nightshade. Nightshade countered with an elegant smile that was about as friendly as Teela’s glare. Helen stepped between them with drinks.

“Candallar is not your problem,” Teela said anyway.

“Did I encounter him while on patrol?”

“He didn’t break any laws.”

“Not on this side of the Ablayne, no. And frankly, I’d like to keep it that way.”

Tain winced. Mandoran whistled.

“While I’m visiting the Consort, I can ask about the Hallionne.”

“I consider that unwise,” Teela replied.

“Probably. But she might have answers that we don’t, and we’re going to need them.”

Mandoran coughed. “I think I’m supposed to say that the Hallionne and our friends are not your problem.”

“If I’d never gone to the green, none of you would be here. You wouldn’t be able to travel. The High Court politicians wouldn’t be up in arms.”

“I don’t think there’s anything wrong with asking the Consort, myself,” Mandoran added.

“There is everything wrong with it at this time,” Tain said. “It may have escaped your notice, but Kaylin is mortal.”

Kaylin tried not to bristle. She failed. “I’m a Hawk.” She folded her arms.

“A mortal Hawk.”

“I was sent to the East Warrens. Not you.”

“You wouldn’t have been sent to the East Warrens if—” He stopped.

“Ifs don’t matter. I was sent. I met Candallar. Candallar is a fieflord, and Candallar appears to be involved. And probably not in a good way, given what happened with the rest of the Barrani Hawks. I won’t push into Teela’s political problems—those are above my pay grade. They’re probably above the Hawklord’s pay grade. But I will talk to the Consort about Candallar.”

“Why would you think she would have any information about Candallar?” As he asked, his gaze shifted to Nightshade.

To Kaylin’s surprise, Nightshade inclined his head. It appeared to surprise some of the Barrani present as well, but did not surprise Annarion. “You are all familiar with Private Neya, surely. She will not pester—” he used the Elantran word “—the rest of the Barrani Hawks. I can give her very little relevant information about the current political substructures in the High Court, or she would pester me.

“She could ask the Lord of the West March, and may be forced to do just that if the situation with your friends deteriorates; he is familiar with Hallionne Orbaranne, and the Hallionne appears to be attached to him. But if his political strength is significant, his reach is compromised by his position; he does not dwell in the High Halls. Any threat of retribution made is made and taken with that understanding: time and distance are issues.

“She could, of course, ask An’Teela, but An’Teela will not answer. She might ask Lord Andellen, but he is almost a political outsider; his tenure as Lord of the High Court expires when Kaylin expires. He cannot build positions of true influence when he serves an outcaste.

“I believe that Kaylin is safe with the Consort; the Consort is safe with Kaylin, and not solely because she is mortal and relatively harmless. We speak that lie frequently, but the Consort does not believe it. Regardless, she will ask. Let her ask there. If she is with the Consort, no one will attack her; if she is with the Consort, none but the most subtle will attempt to engage her at all.”

“Such subtlety does exist at Court,” Teela said.

“Yes.”

“I will go with her.”

* * *

Kaylin used Helen’s begrudged mirror room to make what amounted to an appointment to speak with the Consort; the Consort was not Kaylin, and no one except perhaps possibly the High Lord, just “dropped in” for a visit. Because Barrani didn’t need to sleep, the High Halls were never closed for business. Someone in official, or at least elegant, clothing responded to the mirror, activated it, and—with a narrowing of blue eyes, bid her wait.

He returned, his expression completely neutral, informed her that the Consort was willing to entertain her very “unusual” request, and told her when to arrive.

And then, hearing Annarion’s raised voice in the background, Kaylin cringed and snuck back to her room and her interrupted sleep.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Полная версия книги