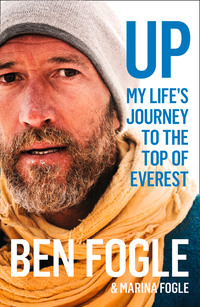

Up

We became a very happy little settlement. I think we reintroduced lost values into our little community. We cared collectively for one another. There was no place for materialism. Our community was based on subsistence. We worked with what we had and maximised our efficiency. After 12 months, we were a happier, healthier, more efficient group of people.

In some ways, I have been chasing that beautiful, simple life ever since.

Castaway for a year on an island, rowing the Atlantic, trekking across Antarctica … all of these experiences have had a profound effect on me.

But it was Everest that changed me for good.

This seven-week expedition into the death zone was a life-changing, life-enhancing adventure. I walked the fine line between life and death. I experienced feelings and emotions that I’d never had before.

I never planned to write a book. After all, thousands of great mountaineering books have been written before. What would make my story so unique? Well, I hope you will read this book, not as an ego-chasing journey to the top of the world, but as a life-affirming lesson.

Humbled and enlightened, I hope these words jump out with the intensity of my own experience. I hope the positivity and the happiness and the joy overshadow the obligatory danger, fear and suffering that comes with a high-altitude mountain adventure.

I hope this book will inspire you to climb your own Everest.

CHAPTER ONE

Family

We were on a deserted beach in the Caribbean when I proposed to Marina.

Over a picnic of tea and sandwiches, I got down and proposed with a ring made from a little piece of string. I had just spent two months rowing across the Atlantic Ocean and hadn’t had time to get to a proper jewellers, so instead I made a special ring from a little piece of rope on the boat.

By the summer, we were married. I couldn’t wait to start my own family, but we decided not to rush into parenthood. It would be several years until Marina fell pregnant for the first time.

I had never been happier. We waited until the 12-week scan to tell everyone. In anticipation, we invited friends and family over for a party. That afternoon, we went for the final scan only to discover there was no heartbeat. We had lost our little child before it had even had time to form. It was crushing, but Marina insisted on going ahead with the party – one of many episodes in our lives that shows her resilience.

A month later, I went to Antarctica with James Cracknell. The polar trek was a pretty good way to overcome the tragedy of the loss. For those who haven’t experienced miscarriage, it can be a difficult thing to explain. To be honest, I had no idea of the emotional disappointment of losing a child at such a young age. It isn’t so much the loss, as the loss of the dream.

For three months, we had dreamed and hoped and planned. Of course, all new parents are warned not to become too hopeful before the 12-week scan, but we were intoxicated by happiness and perhaps confident through hopeful arrogance. We’d be fine, we had assumed.

We survived, and it made us both stronger. Less than a year later, Marina was pregnant again and this time she carried to term until we gave birth to our first child, a little baby boy we called Ludo.

Ludo brought such joy and happiness into our lives. Overnight, this little screaming baby became our world. Parenthood can be pretty overwhelming. As dog owners, both Marina and I had been pretty sure we would find it easy. A dog is, unsurprisingly, very different to a baby. We lived through the fog of broken sleepless nights and slowly life became a little easier.

What surprised me most was my instinctive spirit to nest and protect. Inadvertently, I found myself being more careful. I worried more and became more risk averse.

I don’t know if this is instinctive behaviour or whether it is born from the conventions of society, but I soon found fatherhood to be domineering, not in a bad way, but in an all-encompassing, all-consuming change to my lifestyle.

Ludo became our world. He was our everything. We were dazzled by the beauty of parenthood and that blinded us temporarily to everything else.

Family has always been important to me. I grew up in a tightly-knit family, the middle sibling to two sisters, living above my father’s veterinary clinic. We were close to our extended family, too. My parents gently instilled the core values of family life and it is probably no surprise that we all live within a mile radius of one another in central London.

Fortunately for me, my wife is also from a very close family. Perhaps it was part of the attraction for me. As it happens, I probably now spend more time with her parents and sisters than with my own. We spend most weekends with them in their little cottage in Buckinghamshire and the summer with them in Austria.

Whenever I travel, I am always moved by the intensity of the family dynamic in other parts of the world. Almost every other country places the family at the heart of the nation. Grandparents, aunts, uncles all live together. The very concept of retirement homes or old people’s homes is as alien as the concept of not putting family first. In Britain, I think family is a little more insular. For many it is the tight immediacy of the parents and their children. The wider family is often an afterthought for Christmas or a summer barbecue. The reason I never moved overseas permanently was because of the call of my family. I couldn’t bear the thought of being so far from them all.

To become a parent myself gave me a whole new perspective on life. I now had the parental responsibilities. I had a little child that would rely on me for the next 20 years or so. I was responsible for caring, sharing and preparing this little boy for life.

I had to teach him what was right and what was wrong. What was good and what was bad. Love and hate. Fear and loss. I was overwhelmed at the incredible burden of responsibility. What if I got it wrong? What if I failed? Can you fail at being a father?

No amount of planning or preparation can really prepare you for the magnitude of the journey. You can’t press the pause button. You can’t change your mind. Fatherhood is an unstoppable expedition into the unknown.

Expedition isn’t a bad way to describe it. You try to plan and prepare. It involves a whole new routine that often includes sleep deprivation and fear. It’s like you enter a new world in which you’re never really sure if you are right or wrong.

I felt guilty about taking even the shortest overseas assignments, which was at odds with my instinctive desire to feather my nest financially. Money had never been a priority; of course it is a powerful enabler, but I’ve always been happy with simplicity, and the desire to accumulate great wealth has never been an ambition.

Overnight, this relaxed attitude changed into a sort of panic. As a freelancer, I had no guarantee of work from one day to the next. The vulnerability of a TV presenter cannot be underestimated. Our value can plunge overnight in the blink of a single scandal or change of a commissioner. Fashions change, and with them presenters come and go. As Piers Morgan likes to say, ‘One minute you are the cock of the walk, the next you are a feather duster.’

Most of all, I wanted to be a good role model. I admired, and still admire, both my parents. I am so proud of their achievements, and part of my own drive has been to make them equally proud. For me to succeed in life feels like success for them as parents.

Success isn’t always about impressing other people, but how can you ever define success if there is no one to congratulate you?

It wasn’t long before Marina was pregnant with our second child, Iona. Once again, we dipped into the nocturnal fog of parenthood, and once again I found myself torn by the contradiction of wanting to be a stay-at-home dad. To nurture and protect while at the same time battling my desire to build up my financial resources and work.

It was like trying to juggle too many balls. Family, friends, work, ambition and adventure. You can’t have your cake and eat it. The problem was that adventure has always been at the heart of who I am, and while instinct drove me to nest build, passion for the pursuit of adventure was driving me closer and closer to Everest, my childhood dream.

For as long as I can remember, I have always wanted to climb her. The first time I remember seeing a photograph of Everest was in National Geographic magazine. It seemed so extraordinary that man, with all our advancement, had taken until 1953 to get to the top.

I spent hours staring at those photographs of the towering peak, of weathered faces and heroic sherpas. There was something so romantically mesmerising and alluring about her. Dangerous and beautiful. I found myself dreaming about her. Thinking about her. But it was always just that. A dream. Like the pretty girl at school, I was never going to get her. I wasn’t a mountaineer. It seemed beyond my grasp on so many levels.

I’m not sure what it was that so captivated me. The remoteness. The romance of the highest place on earth. The drama. The tragedy. She has been at centre stage for so many incredible tales. Some heroic. Many tragic. Plenty unexplained.

As a young boy, summiting Everest represented the pinnacle of human endeavour. In my young mind, it was the ultimate achievement. It required grit, strength, bravery and confidence. None of which I had very much of, which is maybe why it had such magnetism. Here was a mountain that attracted the brave few; the romantics pursuing their standing at the top of the world.

Over the years, I had met plenty of people who had climbed Everest: Kenton Cool, Sir Ranulph Fiennes, Bear Grylls, Annabelle Bond, Jake Meyer, the list goes on. To be honest, I seemed to know more people who had climbed it than hadn’t. I felt like the odd one out. It always made me feel like I had missed out on this incredible moment. Not in a ‘bagging’ or ‘ticking off’ kind of a way, but in the pursuit of my dream.

Many people are put off by the number of those who have climbed Everest. Nearly 4,000 have had the privilege of standing on the top of the world. I’d say out of a world population of over 7 billion, that’s still quite small.

It is difficult to define ‘why’. When Mallory was asked he famously answered, ‘because it’s there’. As flippant as it sounds, I can relate to his sentiments. We live in an age where there has to be a purpose and reason for everything we do.

There had never been a clear ‘purpose’ for me to climb Everest. In past conversations with Marina she had quite rightly explained that if climbing and mountaineering was my passion, then I should, and could quite justifiably, attempt a summit, but why? She had asked, why would I risk so much for so little?

Was I not risking my life to simply stand on a point? The answer is yes and no. For me, the Everest dream has always been so much more than just an ego trip. It’s the whole thing. The trek to Base Camp. The Icefall. The Western Cwm, the Lhotse Face, the South Col, the Balcony, the Hillary Step. For me, having read countless books, these places have the same spiritual draw as a pilgrimage.

Everest has always represented everything I dream of achieving. It has always had a wild, dangerous romance that is at the same time both terrifying and electrifying. It fills me, has always filled me, with such wondrous fascination and appeal. Like a forbidden fruit. So close and yet so far. Within touching distance.

It’s like an historian visiting the archaeological sites of the world, or a geographer visiting the geological sites.

I was wrestling with the balance between my need for adventure and my love of my family. Can you justifiably juggle both? Where is the line between sensible and selfish? I had found myself torn between the pursuit of my dreams and my family, who are my everything.

In the end, it comes down to who I am and what makes me who I am. Without travel, without adventure and without wilderness, I am nothing. Life is about embracing the good and the bad. It is the heady mix of fear, danger, adversity, heroics, romance, wilderness, beauty, tragedy, love, loss and achievement. Ultimately, it’s about pursuing our dreams. To dare to do. To dare to go where others fear.

What more can you ask for in life?

Everest would give me all that. It was a gamble. It was risky. There were dangers, but if I wasn’t being true to myself then how could I be honest to my own family? I just had to persuade Marina that climbing the highest mountain on earth was a good idea for all of us.

Marina – Home

For as long as I can remember, Ben has wanted to climb Everest. I guess, when you’re in his line of work, wanting to scale the tallest mountain in the world should come as no surprise. But Ben is a dreamer and I’m a realist, and when he’d talked of his lofty ambition, I’d always pooh-poohed the idea, dismissing his dream.

It’s not that I wasn’t seduced by the world’s tallest mountain in the way that he was. I grew up on a diet of adventure books. I spent my gap year reading the mountaineering authors Joe Simpson and Jon Krakauer. The ambitions of my 18-year-old self, aspirational and seemingly immortal, included participating in the Vendée Globe – the single-handed round-the-world sailing race – and climbing an ‘eight-thousander’, probably Everest, maybe even K2. As I waved Ben off from La Gomera on his mission to row the Atlantic, I was selecting which of my friends I’d ask to be in my team for the same race in two years’ time.

What is more telling is that by the time he’d reached the other end and I’d realised just what such a challenge involved, the idea had been well and truly scrapped. With a new ring on my finger and a wedding to organise, I was delighted to be at Ben’s side as he undertook his challenges. As his wife I would have the best seat in the house, but there was no way I was actually going to do them.

For Ben, however, actually participating in adventures is part of his DNA. My bold spouse is always on the lookout for a feat that will inspire the nation. When Ben announced he was going to row the Atlantic, everyone looked at me incredulously, not believing you could actually row across an ocean that only the most hardy sail across.

In the first few years of our marriage, Ben dabbled with extremes – facing the bitter cold walking to the South Pole and enduring the intense desert conditions walking across the Empty Quarter. Part of me was hoping that this thirst for adventure would cease as our children started needing him more. I was banking on the fact that he’d never get bored of talking about the life he’d led up until this point, and that I could continue to brush the ‘E idea’ under the carpet.

The first time I knew he was serious was on a Sunday afternoon as we walked across the Chiltern hills. The lives of new parents tend to revolve around their children, leaving the parents little time for each other. We’re at the stage where every conversation is hijacked by an eight-year-old.

‘But Mummy, won’t you get put in prison if you kill that traffic warden?’

‘Mummy, what is resting bitch face?’

So last year, we made a conscious decision to try and have an hour when we walk and talk, just the two of us, every weekend. Since Ben is away for most of the year, the reality is that these walks happen once a month. Not ideal but good enough (which as every parent knows, is the gold standard).

Spring was just casting her delicate fingers over the winter-hewn hills. Around us new life was emerging from the rich earth, and blossom buds were tentatively bursting from naked trees. ‘So I think I’ve found a way to do Everest,’ Ben started. I glanced at him and at that moment my stomach lurched, because for the first time I knew he really meant it.

Ben and I don’t have the kind of relationship where he tells me what he’s going to do. I’d never have signed up for that, but as a couple we’re absolutely terrible at conflict and so, over the decade that we’ve been married, we have worked out how to tackle potentially sensitive conversations without it resulting in an argument. We don’t always achieve this, but amazingly, this time it worked.

I’d been told by a therapist that potentially difficult conversations are best had while walking. Raising your heart rate is good for the body and mind, and the fact that you’re looking ahead rather than looking intensely into each other’s eyes takes the edge off it. As we dipped into the Hambleden Valley, he told me his plan; that Kenton Cool, the rock star of the climbing world, had agreed to guide him, that he’d found a sponsor so that we didn’t have to re-mortgage our house. He told me about why he’d always wanted to do it and, while he recognised such a feat would always be dangerous, what he was planning to do to mitigate that risk.

We returned home, our cheeks red from the chilly spring breeze, the dogs exhausted and me understanding that Everest was now a reality.

There was only ever one contender when it came to who could help us achieve this dream: Kenton Cool. I had known Kenton for several years after we had met through a mutual friend, Sir Ranulph Fiennes. He had told me that should I ever decide to do some climbing, we should consider teaming up together. Five years passed before I gave him a call to ask if he would help Victoria and myself with our Everest dreams.

Kenton set out a two-year plan for our Everest attempt. Respect of the mountain and a dedication to the project would ensure we had the best chances of summiting. He wanted to break it up into three phases. The first would involve an Alpine expedition for Victoria to give her a feel for the mountains. After all, while I was still a relative novice when it came to mountain climbing, Victoria was a mountaineering virgin. Green. Once she had become familiarised, we would then head to Bolivia for a three-week training programme in the Andes. This would then be followed by more training in the European Alps, before the final stage which would be a pre-Everest expedition to Nepal.

Kenton is one of Britain’s most respected mountaineers who has an astonishing 12 summits under his belt. His climbing formula has been tried and tested so, although it would mean a huge amount of time away from family and work, I was committed to the plan.

The idea behind the programme was to build up our confidence using crampons, ice axes, ropes and harnesses. By the time we reached Everest, they needed to be second nature. We had to move efficiently and safely. It would also give us a chance to familiarise ourselves with mountain living. Once again, while I had plenty of experience of camping in the wilderness, for Victoria this would be a whole new experience.

Finally, it would also give us two years to get to know one another properly. To understand one another and to recognise our behaviours. The idea being that by the time we reached Everest, we would be able to know when something wasn’t right; we would understand the nuanced behavioural changes that may be a result of altitude sickness.

For someone who has embraced the slow life, I am quite an impatient person, and the two-year plan was a pretty big commitment. To be honest, it was probably tailored more towards Victoria’s inexperience, but we were a team and I relished the time we spent together.

In 2017, tragedy struck our tiny corner of West London. Just a few hundred metres from our house, Grenfell Tower caught alight and took more than 70 lives with her – some were friends. This tight-knit community was torn apart. It is still hard to think about. We pass the charred remains of that tragic building every day and we think about those lives lost.

It turned our little community upside down, but in those awful days and weeks after the inferno, a team of volunteers from the British Red Cross descended on North Kensington. It was both terrible and beautiful to see the same vehicles I had seen so often in faraway lands, now parked on my own street.

When Nepal was devastated by an earthquake back in 2015, the Red Cross had been one of the first aid agencies on the scene. I had long admired the Red Cross and decided that if I was going to climb Mount Everest, it would be in support of their incredible, heroic efforts at home and abroad. The countless volunteers across the world who selflessly dedicate their lives to improving the lives of others is true heroism, way greater than standing on the summit of any mountain.

Marina had given the green light. Kenton had agreed to help us prepare for Everest. We had agreed to support the British Red Cross and Victoria was fully committed to the expedition.

Now all we had to do was learn how to climb.

CHAPTER TWO

Preparation

After a long summer in the Austrian Alps, I left Marina and the children and headed to the other side of the world, to La Paz in Bolivia, where our team would have a crash course in mountain climbing. Kenton had designed an expedition that would take us up four Andean peaks in ascending order, culminating in Illimani at just under 6,500 metres (or three-quarters of the height of our ultimate goal, Everest).

I had only met Victoria a handful of times, and although I had known Kenton for a few years, we were all comparative strangers. This would be a great opportunity to get to know one another, and also to see if we were suited to mountains.

I had made it very clear to Victoria that she had to be 100 per cent sure that she wanted to take on the highest mountain in the world. I knew the risks involved. Everest required respect and commitment. The two-year plan we had embarked on would take us away from families and work for long stretches, so we had to both be fully invested. I felt a sense of responsibility that would be mitigated by Victoria’s full commitment and devotion to the expedition. While mine was a childhood dream to climb Everest, hers was more about the ‘challenge’.

It was early morning when we landed in the highest capital city in the world, La Paz. At 4,000 metres, it is so high that emergency oxygen cylinders are provided around the airport for new arrivals struggling with the thin air.

Our little minibus hurtled through the empty streets. La Paz really is an astonishing city. In the bowl of a valley, it is surrounded by towering snow-capped peaks. We explored the city for a day or two to acclimatise, even visiting the Witches’ market with its dried llama foetuses, snakes, herbs and spells. There is something rather overwhelming in the enduring practice of witchcraft and folklore remedies.

We left the city for the peace and tranquillity of Lake Titicaca, the highest navigable lake in the world. I had first come here as a 19-year-old. I never forgot the haunting beauty of the lake with its floating reed islands and the fishermen’s iconic boats. We spent a day sailing the lake on a reed boat, stopping at the Island of the Sun for an afternoon hike. Slowly, the three of us were getting to know our different personalities and discovering how we might work as a team: Kenton, the slightly laid back and forgetful mountain guide (so forgetful he had failed to pack a headtorch and a satellite phone for the final peak); Victoria, the vegan and ex-Olympian; and me, the romantic daydreamer.