Happy Mealtimes for Kids

Copyright

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street, London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2012

FIRST EDITION

© Cathy Glass 2012

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Cathy Glass asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN 9780007497485

Ebook Edition © September 2012 ISBN: 9780007497492

Version 2020-01-28

Contents

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

INTRODUCTION: WHY HAPPY MEALTIMES?

ONE: WHAT IS A BAD DIET FOR KIDS?

Diet and behaviour

Sugar

Caffeine

Food additives

TWO: WHAT IS A GOOD DIET FOR KIDS?

Calories

Ideal weight

Protein

Carbohydrates

Fibre

Fat

Vitamins and minerals

Fluid

THREE: MEALS AND EATING

The importance of mealtimes

Establishing good mealtimes

Food fussiness and refusal to eat

FOUR: BREAKFAST

Breakfast routine

Breakfast food

Drinks for breakfast

Quick breakfast ideas that kids love

Cereal

Toast

Bread rolls

Bagels

English muffins

Croissants

Fruit

Yoghurts

Smoothies

Cooked breakfasts

Full English breakfast

Omelette

Boiled egg with soldiers

Egg/sausage/tomatoes/baked beans/cheese/mushrooms on toast

Eggy bread

Welsh rarebit

Toasted sandwiches

Pancakes

Leftovers

School breakfast

Breakfast for adults

FIVE: LUNCH

School dinner

Packed lunch

Drinks for a packed lunch

Bread, wraps and rolls

Fillings

Pots

Little extra pots

Main meal pots

Other savouries for a lunch box

Packed lunch desserts

Lunch at home

Jacket potatoes

Kids’ hash

Egg in a nest

Stuffed pepper

Quick cauliflower cheese

Sausage and rice pan casserole

Soups

Potato and carrot soup

Lentil soup

Cream of mushroom soup

Pasta lunch

Cheesy pasta

Macaroni cheese

Tomato pasta

Pasta bake

Spaghetti

Tagliatelle

‘Toast lunch’

Toasted sandwiches

Kids’ kebabs

Bubble and squeak

All-day breakfast

Lunchtime desserts

Fruit

Smoothies

Yoghurt

Other lunch dessert ideas

Drinks at home

Convenience food for lunch

SIX: DINNER

Easy and popular main meals

Spaghetti bolognese

Cottage pie

Lasagne

Toad in the hole

Onion gravy

Curry

Plain naan

Casseroles and hot pots

Meat and vegetable casserole

Vegetable casserole

Hot pot

Fish and sweetcorn pie

Stir-fries

Simple stir-fry

Simple stir-fry sauce

Beef and baby sweetcorn stir-fry

Honeyed chicken and noodle stir-fry

Other stir-fry ideas

Meat and two veg

Roasting meat

Braising meat

Stewing meat

Grilling meat

Frying meat

Puddings

Apple crumble

Bread and butter pudding

Fruit pie

Rice pudding

Bread pudding

Sponge pudding

Cake in custard

Banana and honey whip

Cheesecake

Trifle

Convenience food for dinner

SEVEN: HAPPY SNACKS

CONCLUSION

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

CATHY GLASS

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

Introduction: Why happy mealtimes?

I am a foster carer, and as well as bringing up three children of my own, I have looked after other people’s children for over twenty-five years. Some of those children stayed with me for a few days, while others stayed for years. The reasons why children come into care vary – from a single parent having to go into hospital for a night, to a child being badly neglected and abused. While some of the children I’ve fostered had received adequate diets at home, the vast majority – over 95 per cent – had not, resulting in the children being under- or overweight, short in stature, with dull skin and hair, lacking energy, and often having difficulties in concentrating and therefore being behind with their learning.

One of the first changes I have to make when a child comes to live with me is to their diet, and they are often resistant to change. When the children have been used to snacking on whatever was to hand – usually crisps and biscuits – not only do I have to wean them on to ‘proper’ food but also I have to introduce them to mealtimes rather than having snacks in front of the television. Highly processed food – usually the only food they have known – is often visually attractive and easy to eat (requiring hardly any chewing), but it has few nutrients and addictive amounts of salt and sugar. I have to win the children over to a healthier way of eating as well as providing meals that the whole family enjoys, and like most busy parents I don’t have much time. I have therefore become adept at producing simple nutritious meals that are easy to make and which kids of all ages will love. In this book I share my recipes, together with some important food facts. I hope you find it useful. Bon appétit.

CHAPTER ONE

What is a bad diet for kids?

No food is actually ‘bad’ for a child, unless it is poisonous or the child is allergic to it, or is on a restrictive diet, but some foods become ‘bad’ because of the quantity in which they are eaten. A poor diet is usually high in sugar and fat, low in protein, and lacking in vitamins and minerals. So, for example, a packet of crisps in a lunch box alongside a sandwich containing protein (such as meat, fish or eggs) and a piece of fruit is fine, but four packets of crisps a day are not, especially when they replace a meal. Likewise a piece of chocolate or a cup cake in addition to a main meal is acceptable, but chocolate and cake regularly eaten in large quantities are not. Crisps, chocolate and most heavily processed snack foods are high in calories, salt, sugar and fat, and low in nutrients, so must be eaten in moderation.

You may find it incredible that a child could ever be given chocolate or crisps instead of a meal, but many of the children I have fostered had been used to substituting this type of food for meals before they came into care. Breakfast, often bought from the corner shop and eaten on the way to school, would be a chocolate bar, or a bag of crisps and a can of fizzy drink, while the evening meal would be whatever the child could find in the cupboard, and very likely sugar-laden cereal and a packet of biscuits. Often the only ‘proper’ meal a child had, therefore, was the free school dinner from Monday to Friday. While this type of eating applies to the minority, many children from good homes are overweight and lack essential vitamins and minerals simply because their diets are too high in processed foods. These are attractively packaged and sold to us through advertising on the television. How many of us as parents have given in to our child’s pestering in the supermarket and bought a ridiculously expensive, attractively packaged (sugar-laden) cereal because our child had seen it advertised? I’ll admit I have.

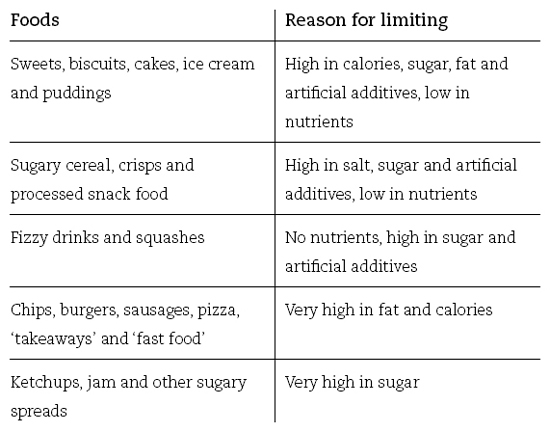

Many governments across the world are now so concerned about the poor quality of children’s diets that they are funding initiatives to try to change the eating habits of a generation. Not only does a bad diet stunt a child’s growth and development, and cause obesity and lethargy; it can also produce behavioural problems. I mentioned this in my book Happy Kids (a guide to raising well-behaved and contented children) and received hundreds of emails from parents who, after reading my book, suddenly connected some foods with their child’s bad behaviour. More of that later, but first let’s look at the foods that should be limited in a child’s diet:

You will probably think of others. Generally speaking, if food is heavily processed and not fresh it is likely to be high in calories, sugar, fat, salt and artificial additives and should be limited. Fortunately ingredients now have to be listed on the food packaging, so check if you are unsure. And remember the ingredients are listed in descending order of the amount included – with the highest first – so if the first ingredient listed is sugar, as with most sweets, then sugar is what that food contains most of. But also remember that a good diet for kids is about limiting these foods, not banning them completely.

Diet and behaviour

‘We are what we eat’ is a well-known phrase, meaning the food that goes into our mouths is absorbed by our bodies and therefore becomes part of us. This is especially true for children, who are still growing and use a larger proportion of their food for growth, as well as cell repair and general health, than adults do. But it isn’t only the child’s body and physical health that are at the mercy of what the child consumes, but also the child’s brain and central nervous system. A finely tuned endocrine and hormone system is responsible for mood, behaviour and mental health, and this relies on a well-balanced diet to function efficiently. There is now a wealth of scientific information – from studies and research – that shows that children’s (and adult’s behaviour) is greatly affected by diet. A healthy diet is therefore essential for both children’s physical development and their emotional and mental well-being.

Sugar

Apart from obvious sugar-laden foods – sweets, biscuits, cakes and puddings, etc. – sugar is added to many other processed foods: for example, baked beans, soups and even some bread. As a result our children have become a nation of ‘sweet tooths’. As well as having detrimental long-term physical effects – tooth decay, obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, etc. – too much sugar can have an immediate effect on mood and behaviour. Most parents have observed the ‘high’ that too many sweet foods or sugary drinks can have on their child – even the average child without a hyperactivity disorder. The reason for this is that as sugar enters the bloodstream it gives a surge of energy, so the child rushes around on a high; but after the ‘sugar rush’ comes a low as the body dispenses insulin to stabilize itself. The child then becomes tired, irritable and even aggressive, with a craving for something sweet. So begins a pattern of sugar-related highs and lows, and if the child is prone to mood swings or hyperactivity, refined sugar will fuel it. Sugar intake should therefore be moderated and ideally from a natural source, for example, fruit or honey.

Caffeine

Although it is unlikely you will give your child a cup of strong black coffee, the equivalent amount of caffeine can be found in a can of many a fizzy drink, added by the manufacturers. Caffeine is a powerful stimulant – which is why many adults drink coffee in the morning to wake them up. Caffeine acts immediately on the central nervous system, giving a powerful but short-lived high. Some bottles and cans of fizzy drink now state that they are ‘caffeine free’, but they are still in the minority, and you will need to check the label to see if caffeine is present, and in what quantity.

Children’s sensitivity to caffeine varies, but studies have shown that even children who are not prone to ADHD (Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder) can become hyperactive, lose concentration, suffer from insomnia and have challenging behaviour when they drink caffeine-laden fizzy drinks. Caffeine is also addictive, and many children are addicted (from regularly consuming fizzy drinks) without their parents realizing it. The child craves and seeks out the drinks, and suffers the effects of withdrawal – headaches, listlessness, irritability – until they have had their daily ‘fix’. Caffeine is best avoided by all parents for their children, and if your child has behavioural problems, particularly ADHD, it is absolutely essential to avoid it. There are plenty of enticing soft drinks and juice alternatives available that don’t have added caffeine.

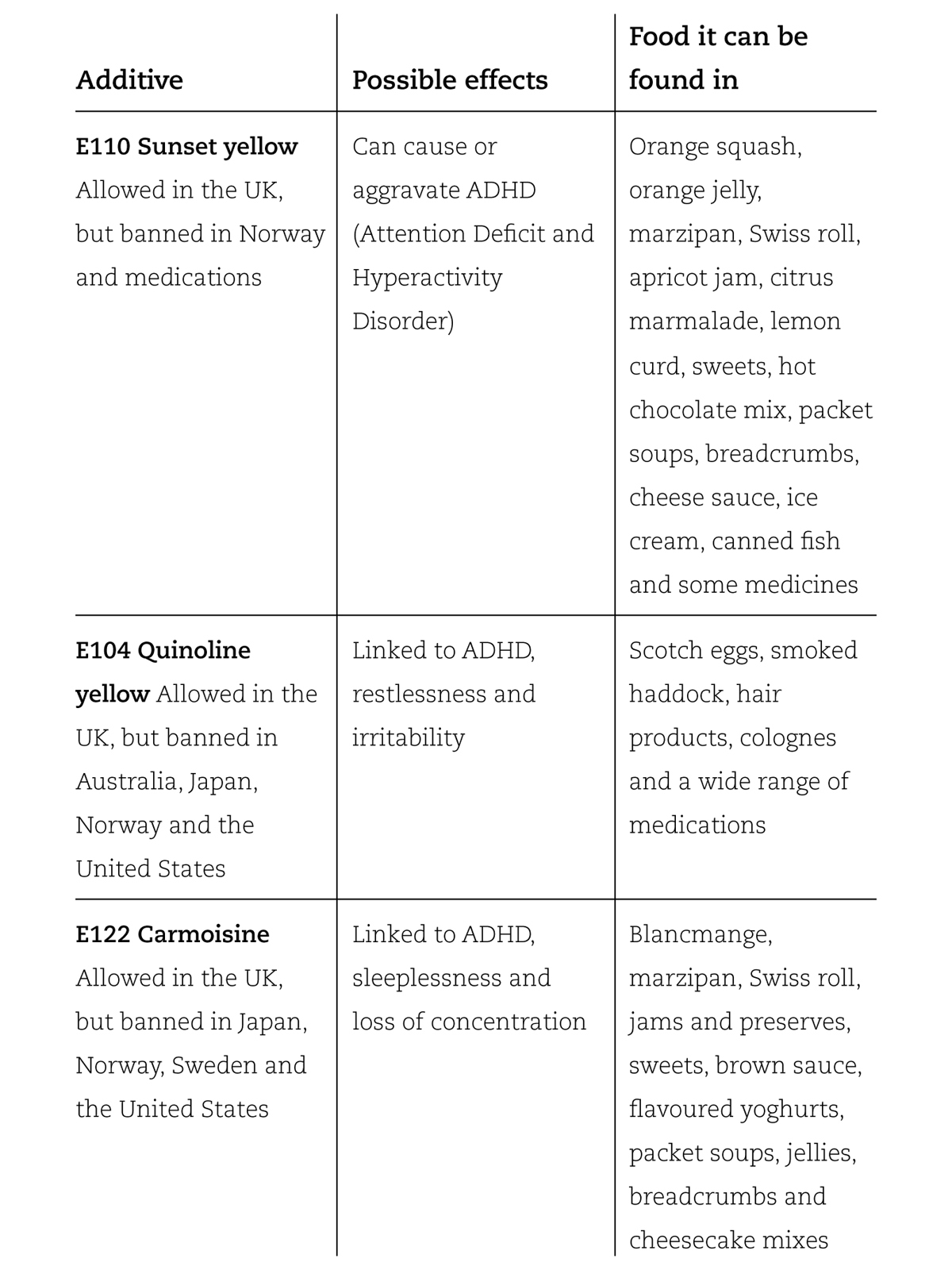

Food additives

Any chemical that is added to food or drink is given an E number. E-numbered chemicals are added for many reasons, including appearance, shelf life, texture and taste. All food additives, including those with E numbers, must be listed on the label of the food package, but only European countries have adopted the E number classification. Although each chemical additive is tested and has to pass health and safety checks before being allowed into food, what isn’t tested is the combination of chemicals, and how this combination reacts in the food or the body. Most processed food and drink contains more than one additive, with a packet of brightly coloured sweets containing upward of ten. Even an innocent-looking yoghurt can contain five or more additives if it is sweetened or made to look like the colour of a particular fruit.

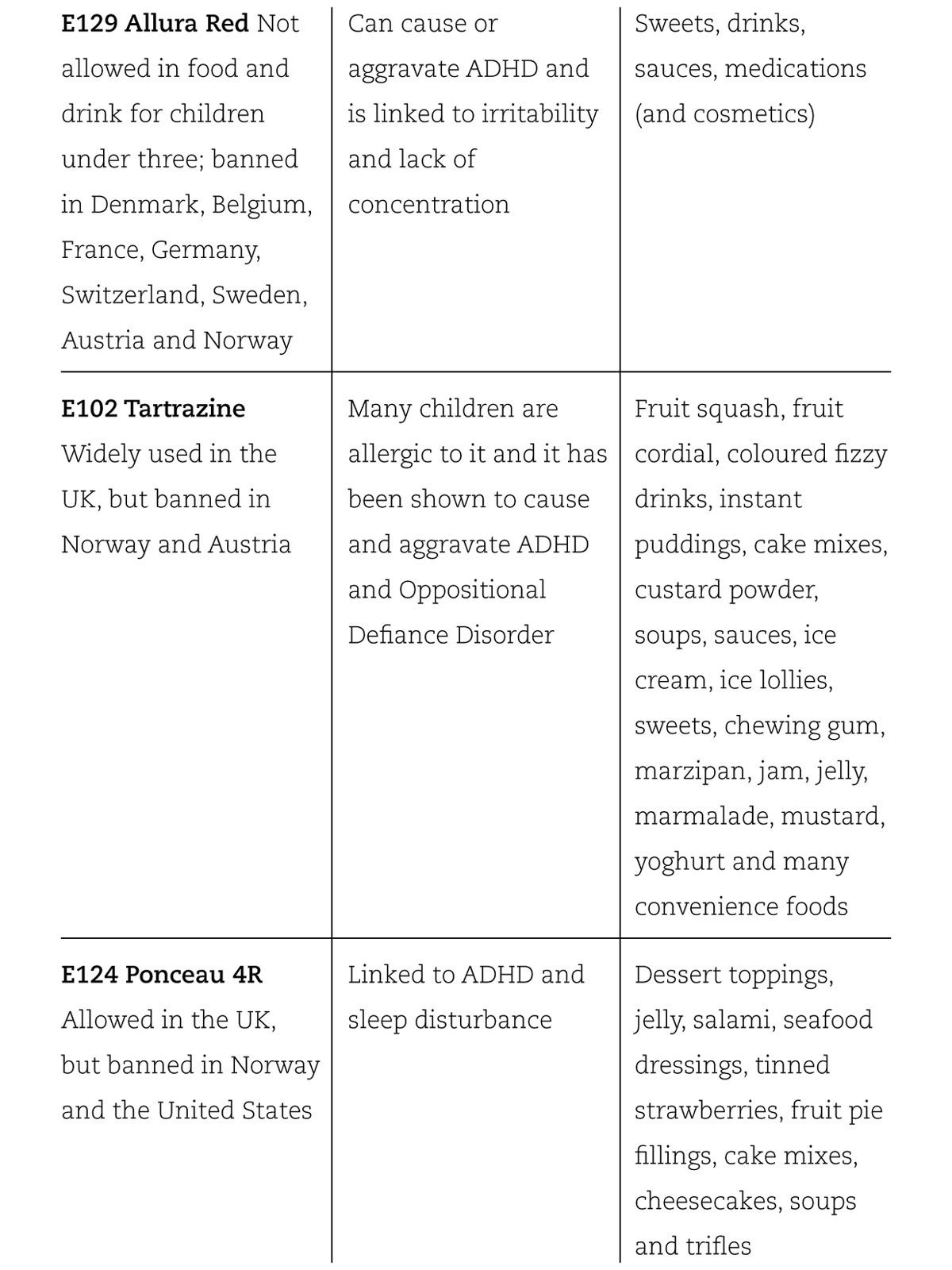

Not all additives are synthetic or have harmful effects, and some have been used for years. Many children suffer no ill effects from eating additive-laden processed food, although cause and effect may not be recognized. While you may spot a link between the stomach ache or sickness your child develops after eating a specific food, a headache after eating a doughnut with bright pink icing, for example, may be missed. The full- and long-term effects of consuming additives are not known and research is ongoing. But there is enough evidence to show that as well as some children experiencing physical reactions to additives, mood, behaviour, learning, energy levels and concentration can be affected. Here is a list of additives that research has shown can cause problems in behaviour, but the list is by no means complete:

If you know or suspect your child is sensitive to certain food additives, then it is obviously advisable to avoid food and drinks that contain them.

CHAPTER TWO

What is a good diet for kids?

We all accept that a healthy, well-balanced diet is essential for our child’s physical and mental well-being, but what exactly is a well-balanced diet and which foods are best and why? Children need protein, carbohydrates, vitamins and some fat in their diet just as adults do, but they need them in different quantities: more of that later. The best way to make sure your child receives a good diet is to provide a variety of foods, using fresh unprocessed food wherever possible, and limiting foods high in fat and refined sugar. So what exactly does a child need?

Calories

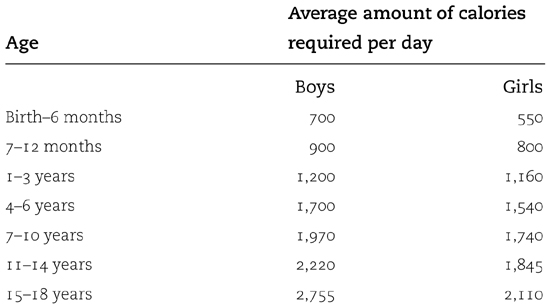

A calorie is a unit of energy, and the calories in food provide the fuel our bodies need in order to work. Without them our hearts wouldn’t beat, our legs and arms wouldn’t move and our brains would stop working. The body takes the calories it needs from the food we eat and stores any extra as fat, so that if we eat too many calories we put on weight and if we eat too few we lose weight. A child’s calorie requirement is different to adults’ and depends on their age, size and how active they are. Children who are going through a growth spurt need to increase their calorie intake, and boys usually need more than girls because they have bigger frames. Now follows a general guideline to the number of calories your child will need, but it is general – based on averages. In the first six months a baby will obtain most, if not all, of its calories from milk.

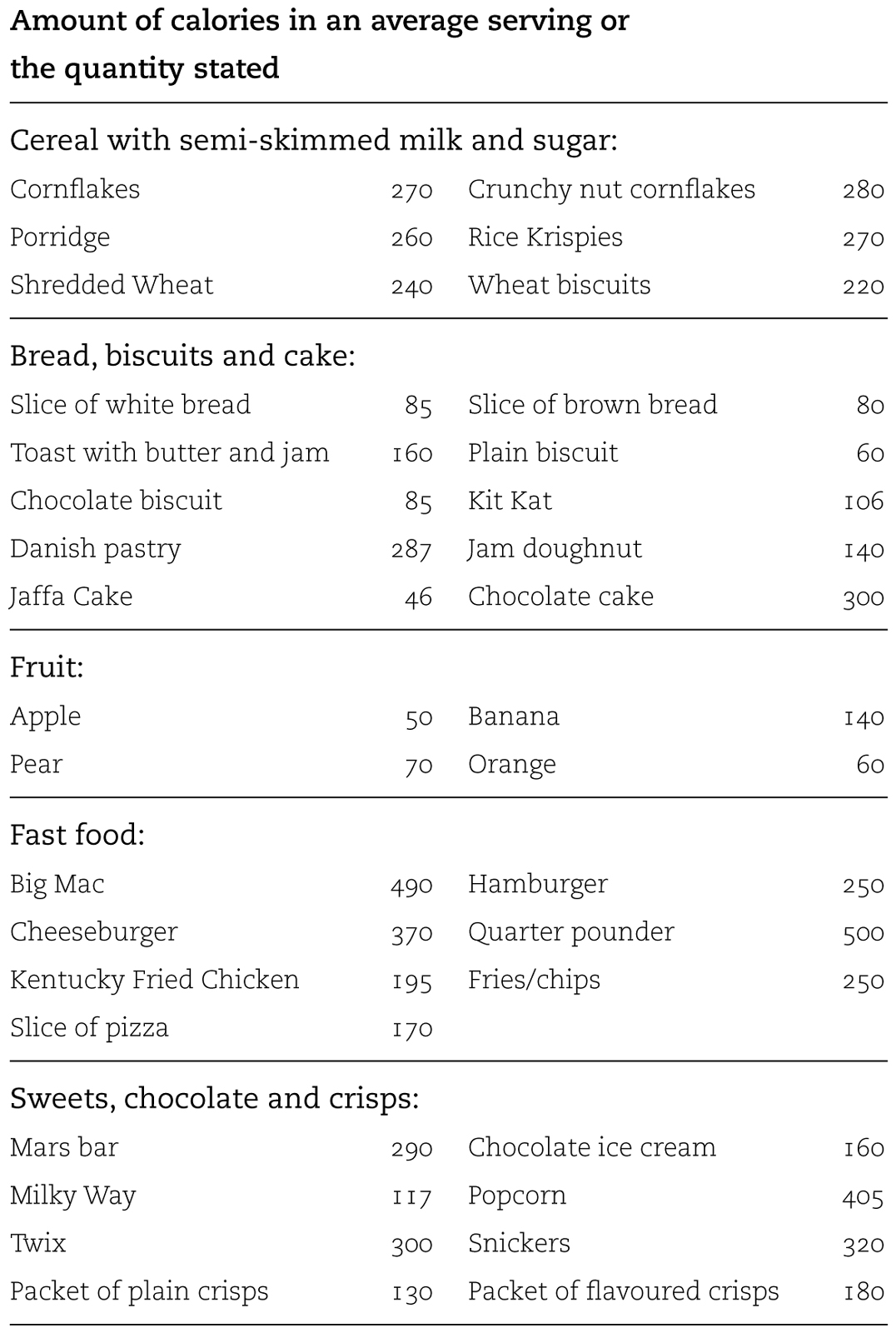

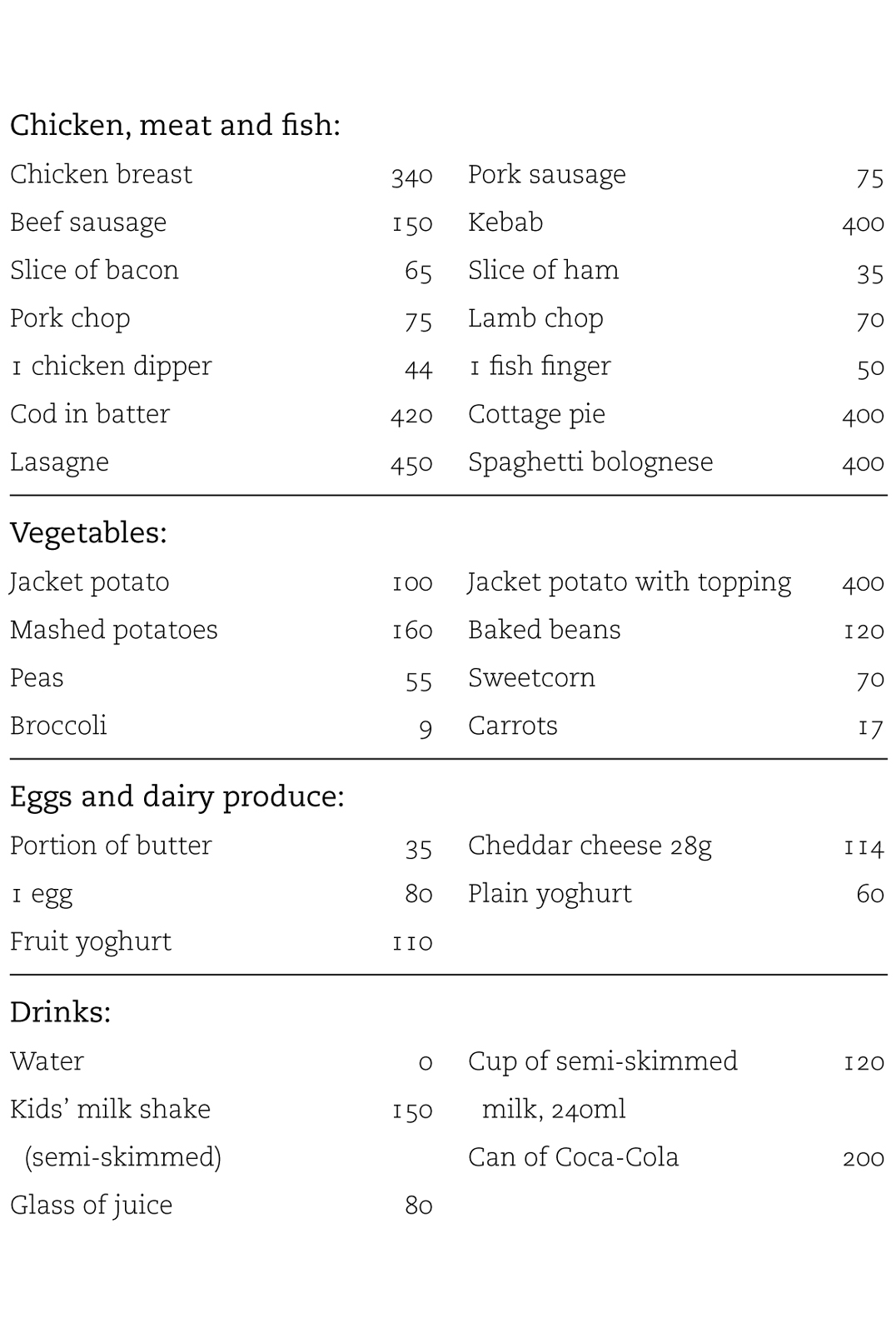

Everything we eat or drink, except water, contains calories. Most packaged food shows the number of calories the food contains on the label. No child should ever be calorie counting; it is the parent’s or carer’s responsibility to ensure their child receives a good diet, which will include sufficient calories for growth and development but not so many that the child becomes obese. Clearly I haven’t the space here to list the calorific content of all foods but here is the amount of calories in some of the foods popular with children.

Ideal weight

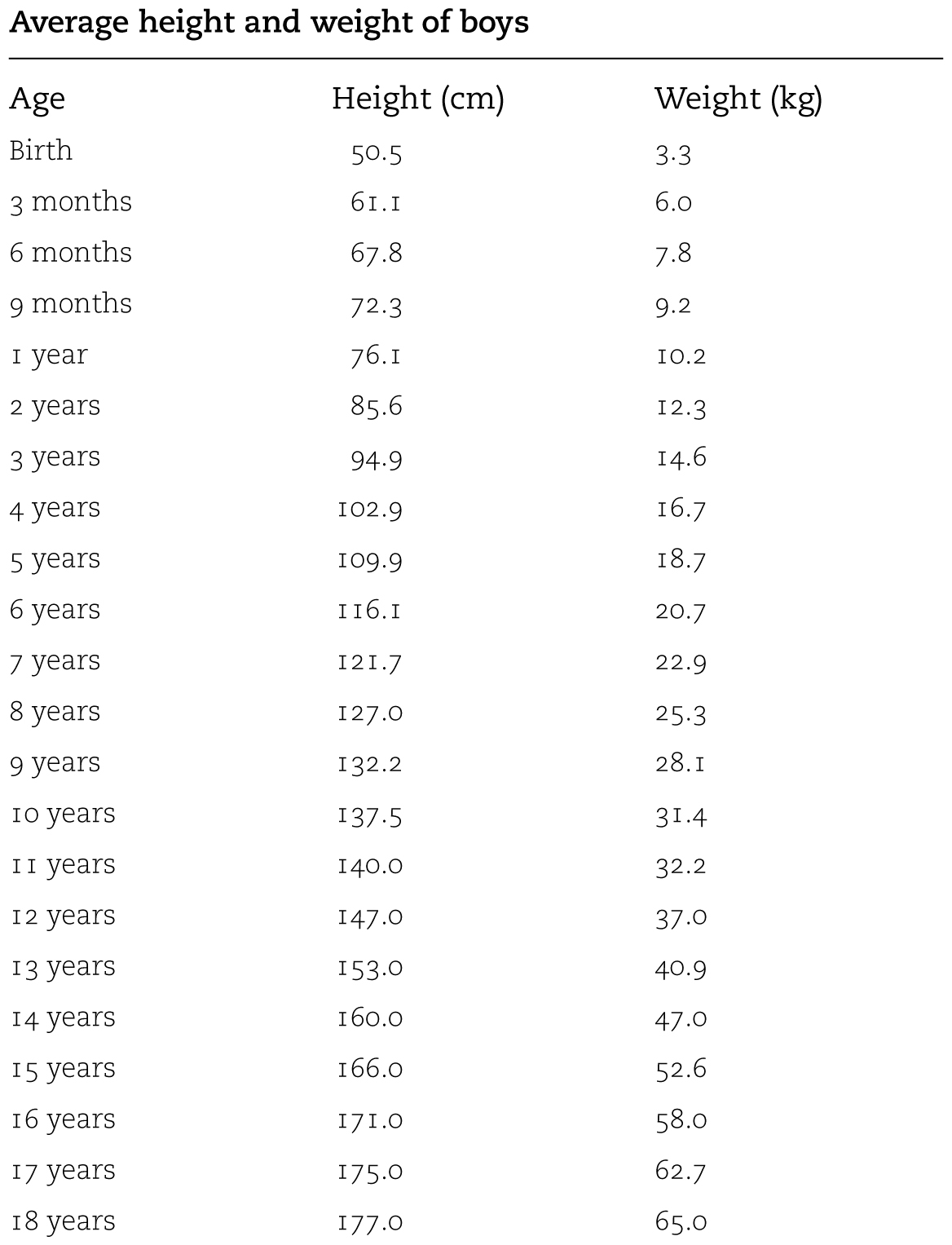

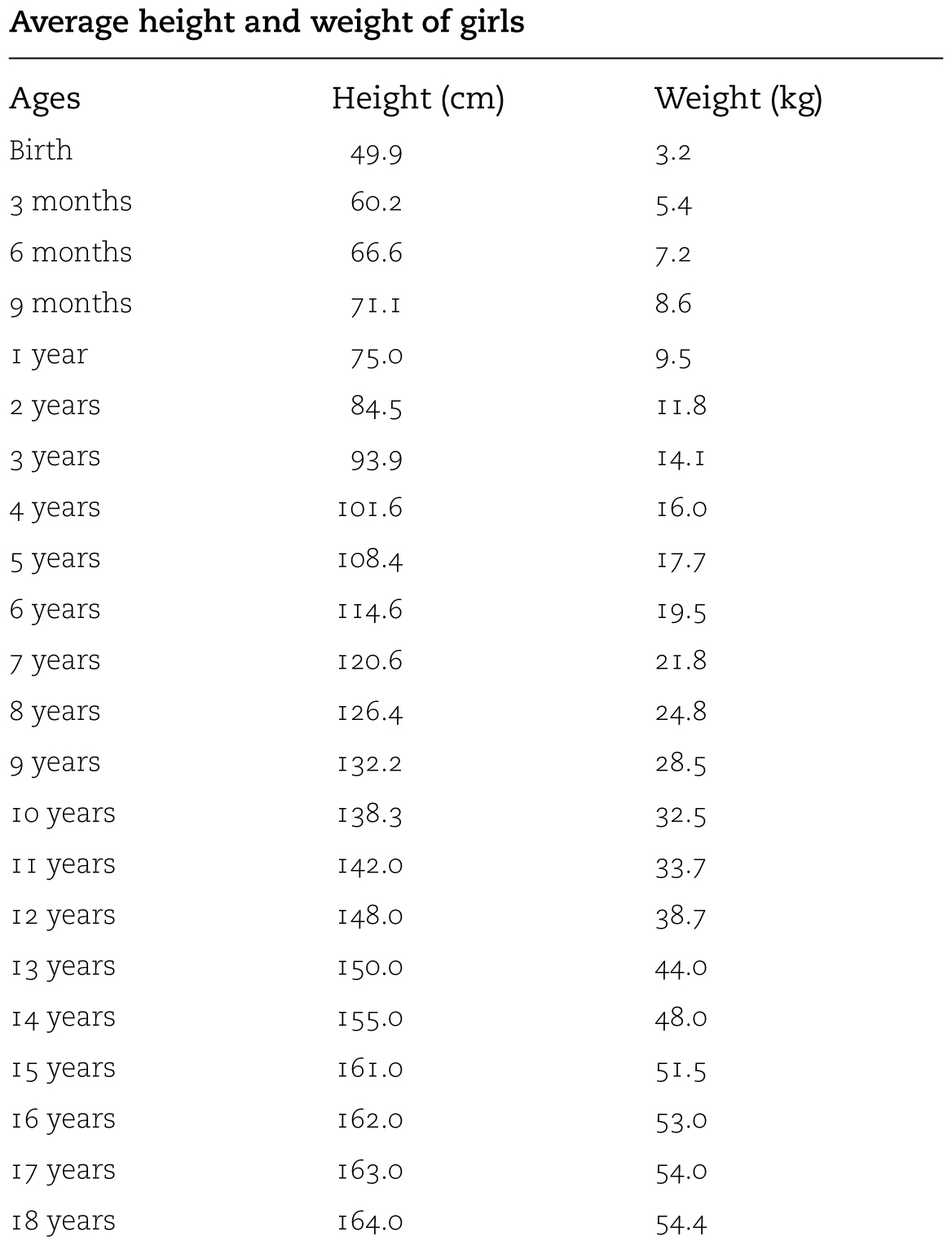

Height and weight charts have largely been replaced by BMI (Body Mass Index) as a way to calculate the correct weight for a child (and adult). However, the calculators can sometimes be complicated to use and the results difficult to interpret, so now follows a general guideline on what your child should weigh at a given height. Remember the heights are averages, so your child will very likely be slightly above or below.

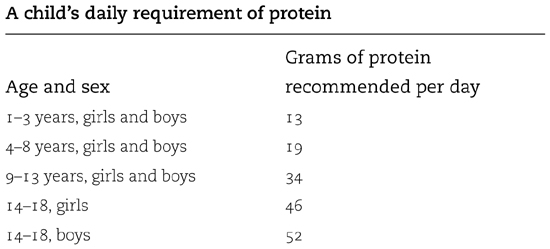

Protein

Protein is another essential requirement in a child’s diet. Protein is the building block of life. Every cell in the human body contains protein, and protein is needed for growth and repair.

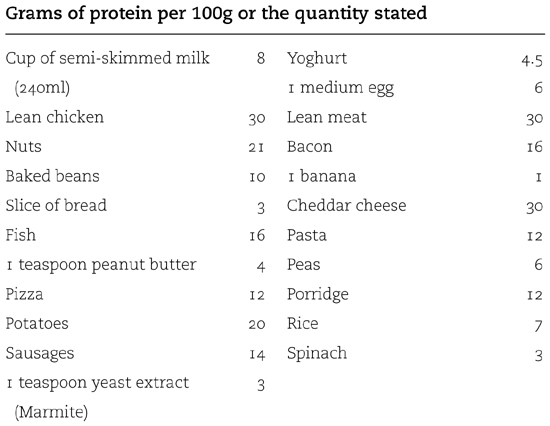

Most food that is packaged lists the amount of protein per gram the food contains on the label. If protein is not shown, then the food doesn’t contain any protein. However, although this information may be helpful, if a child is given a well-balanced, varied diet which includes protein at the main meal they will have enough protein for their needs. Protein is found in many foods, even in small amounts in cake and bread. Foods rich in protein should be included daily in a child’s diet and these are:

* meat, poultry, fish, shellfish and eggs

* beans, pulses, nuts, grains and seeds

* milk and milk products

* soya products and vegetable protein foods

Some typical values of protein-rich food are:

Carbohydrates

The carbohydrates our bodies take from the food we eat are our main source of energy. The more active a child is the more carbohydrate he or she will need. Carbohydrates also have the function of setting protein to work – for growth and repair – which is why the two food groups are eaten together: meat and potatoes, bread and cheese, etc. There are two types of carbohydrate – complex and simple – and the body needs both of them:

Complex carbohydrates are found in fresh and processed foods and are sometimes called starchy foods. Foods providing complex carbohydrates include: bananas, beans, brown rice, chickpeas, lentils, nuts, oats, parsnips, potatoes, root vegetables, sweetcorn, wholegrain cereals, wholemeal bread, wholemeal cereals, wholemeal flour, wholemeal pasta, and are considered ‘good’ carbs. Refined starches are also complex carbohydrates but are not so good because the refining process removes nutrients from the food and concentrates the sugar. They are found in: biscuits, pastries and cakes, pizzas, sugary breakfast cereals, white bread, white flour, white pasta, white rice.

Simple carbohydrates are also known as sugars – natural and refined. Natural sugars are found in fruit and vegetables. Refined sugars are in: biscuits, cakes, pastries, chocolate, honey, jams, jellies, sugar, pizzas, processed foods and sauces, soft drinks, sweets, snack bars.

Children over two should have a diet where approximately half their calories come from carbohydrates, and preferably from ‘good’ sources, so the amount of refined sugar and starch – from cakes and biscuits, etc. – is limited. But there is no need to carb count. If your child is eating a variety of foods in well-balanced meals they will be eating the carbohydrates their body needs.

Fibre

Fibre is another important component in a healthy, balanced diet and many children don’t eat enough fibre. We obtain fibre from plant-based foods: for example, fruit, vegetables, wholemeal bread and pasta, and some cereals. Not only is fibre good for the digestive system (it prevents constipation), but it is also good for the heart and for blood circulation, and lowers cholesterol and blood sugar levels, so preventing diabetes in later life. Fibre provides bulk to a diet, so any child on a weight-reduction programme would be advised to eat a high-fibre diet, which will make them feel full and therefore control hunger and appetite.