The Skills

Interestingly, the picture for Chinese business is considerably better, with women holding 31 per cent of senior leadership roles. It’s a proportion matched in Africa and exceeded in Eastern Europe, but higher than businesses in the European Union (27 per cent) and in North America (21 per cent).3 Notably, the study by Grant Thornton International found that those countries with the most policies in place to promote equality – equal pay, parental leave, flexible working – were not necessarily those with the greatest diversity at the top of business. Policy alone was not producing large scale change, they said, while stereotypes about gender roles were still a barrier to progress. That is a conclusion that perhaps makes clearer where the focus for my generation and younger women should lie – we need to think about individuals as well as institutions.

We can take heart, however, from studies that have compared companies’ records on diversity and their performance – one analysis of more than 20,000 firms in 91 countries found that the presence of women in corporate leadership correlated positively with profitability.4 Another, from consultants at McKinsey, reported that a correlation between gender and ethnic diversity and financial performance generally holds true across geographies. While they couldn’t say that one caused the other, they observed a ‘real relationship between diversity and performance’ and said the reasons for it would include ‘improved access to talent, enhanced decision making and depth of consumer insight and strengthened employee engagement and licence to operate’.5

A broad perspective on where there’s been progress – and where there are gaps – comes from the World Economic Forum’s annual analysis of gender-based disparities. In recent years it has found that the countries studied had made great strides in two key areas – health and educational attainment. The major gaps lay in two others – political empowerment and economic participation and opportunity.6 Its reports have also highlighted how women are likely to be affected by key future trends: automation will significantly affect industries in which many are currently employed, and they are under-represented in high-income and high-growth fields such as technology and science. Even countries where women have made great strides cannot be assured of future progress, explains the organisation’s head of education, gender and work, Saadia Zahidi: ‘A lot of advanced economies have stalled as they were riding the wave of the education boom among women, but if the responsibility of home and childcare is still on those women, there is a limit to how much they can do in the workplace.’7

India is a country where the growth in girls’ education hasn’t resulted in women entering the workforce in the numbers you might expect or hope for. In fact, according to the Harvard economist Professor Rohini Pande, female participation in the Indian labour market fell between 1990 and 2015, down from 37 per cent to 28 per cent. It’s not a lack of political will to get more women into paid employment, she says, or a lack of interest from women themselves. Instead, there is a significant role being played by social norms – among parents, husbands and parents-in-law – about appropriate behaviour for women. Pande’s research also suggests that while low pay is the main reason for Indian men to leave a job or not accept one, women cite family pressures and responsibilities.8

Those pressures might relate to taking care of the household, but also basic mobility, such as requiring permission to go out. As Professor Pande says: ‘It’s pretty difficult to look for a job if you can’t leave the house alone.’ Even in India’s urban areas, she and her associate Charity Troyer Moore found female workers struggling to access male-dominated networks. ‘Women often end up in lower-paid and less-responsible positions than their abilities would otherwise allow,’ they say, ‘which, in turn, makes it less likely that they will choose to work at all, especially as household incomes rise and they don’t absolutely have to work to survive.’9

Nonetheless, the experience of a country like Bangladesh, with similar social and cultural norms to India, shows that there are ways such barriers can be tackled. It has a higher proportion of working women than India, largely thanks to the development of its garment industry, where 80 per cent of the workers are female. On a trip there in 2015, I saw for myself the difference that a job in one of these factories can make to an individual’s life. In a room packed with rows of women at sewing machines, one young worker’s ID card, hanging around her neck, bore the photograph of a young boy on the reverse. She was a widow and this was her only child. His future was her biggest motivation and she was able to pay for his education thanks to her job – without it, they would both be dependent on the mercy of relatives. Indeed, Pande and Moore say the garment sector has been important for Bangladeshi women’s empowerment far beyond the factory floor: ‘The explosive growth of that industry during the last thirty years caused a surge in large-scale female labour force participation. It also delayed marriage age and caused parents to invest more in their daughters’ education.’10

In the UK much of the conversation about workplace gaps between men and women has focused on pay, especially after a 2017 law required larger employers to reveal the difference in the mean and median pay of male and female workers. As this gender pay reporting is based on averages it is in some ways a crude calculation – the airline easyJet, for example, reported a particularly large gap because men dominate its cohort of pilots, who are paid considerably more than the mostly female cabin crew.

It does, however, shine a light on representation and getting women into higher-paid roles, which is why Carolyn Fairbairn of the Confederation of British Industry welcomes it: ‘This is about fairness but it’s also about productivity in our economy and how we have businesses that have all the talents. We do not have enough women who are pilots, or CEOs who are women, or enough top senior consultants in hospitals who are women. These are issues that we now need to really grip.’11 Some believe the obligation to report has transformed companies’ conversations about gender. ‘When we’ve talked about the pay gap before, the response has always been “That must be happening somewhere else”,’ says Ann Francke of the Chartered Management Institute. Now, she says companies are being forced to confront their data and reflect on the picture it paints.12

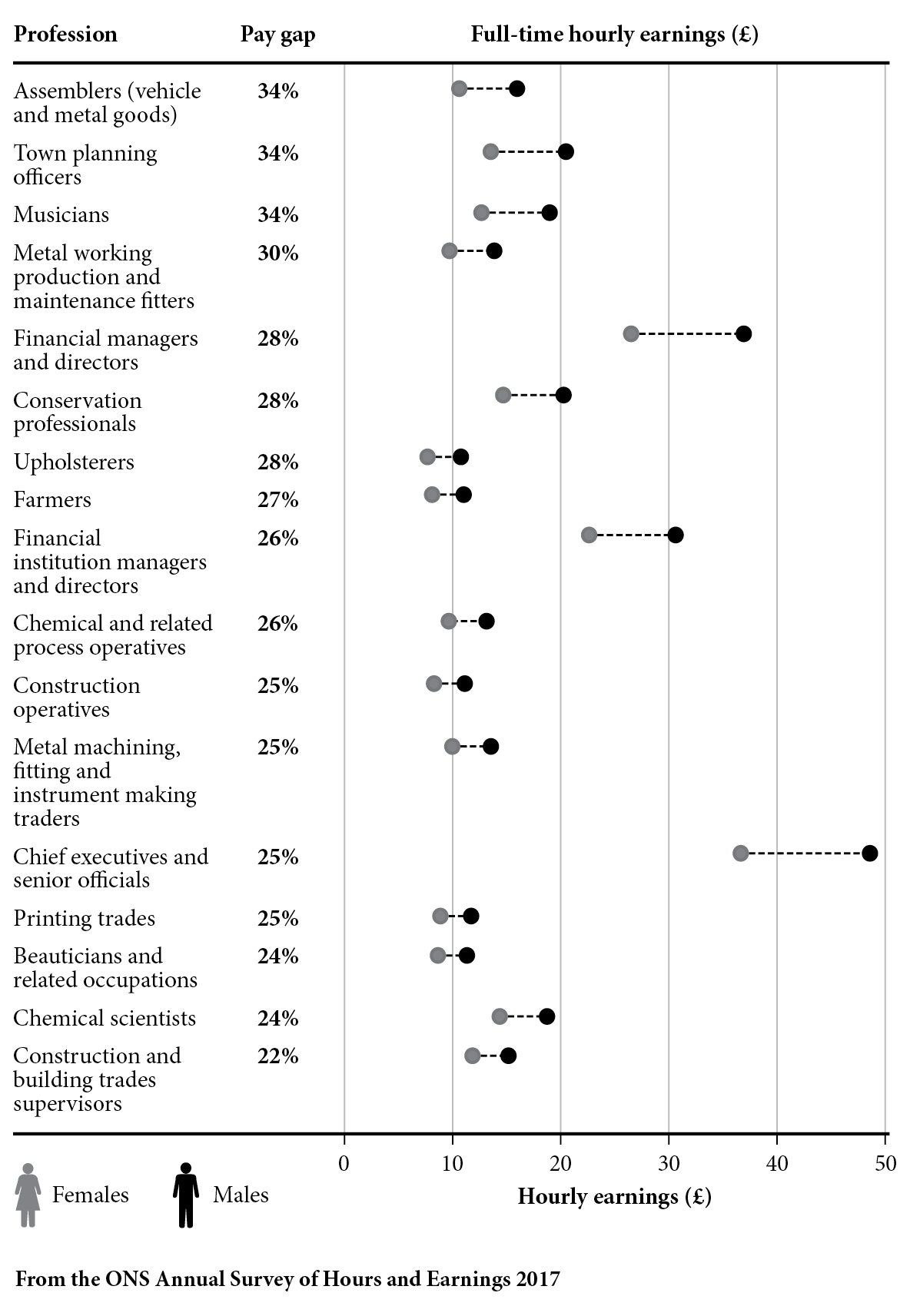

Elsewhere, other data allows comparisons of pay for men and women who have the same professional occupation. A 2017 data set from the UK’s Office for National Statistics showed considerable gender variation in average hourly earnings in many of them. Among full-time financial managers and directors, for example, men earned an average of £35.52 per hour (or £72,000 per year), and women £24.29 per hour, translating into an annual salary of around £43,000. The pattern was similar for town planning officers, musicians, scientists and chief executives. Most of the roles where the gap disappeared or was reversed, so that women were earning more (secretaries and fitness instructors, for example), had hourly earnings at the lower end of the spectrum.13

It is possible that these comparisons mask variations about the work done within the different categories: the scope and responsibility of the roles, whether the jobs were in the public or private sector, the region in which they were based and the skills, experience and competence of the individuals whose information went into the data set. But like companies’ gender pay gap figures, they can be a valuable starting point for a conversation about disparities. Perhaps the women had previously taken time out from work or been part-time for a period – but would that, or should that, fully account for the gap with comparable men once they returned to full-time?

According to the Institute for Fiscal Studies, part-time work can have a striking effect in shutting down normal wage progression. In general, pay rises with experience, but part-time workers, who are mostly women, miss out on these gains. ‘By the time a first child is grown up (aged twenty), mothers earn about 30 per cent less per hour, on average, than similarly educated fathers. About a quarter of that wage gap is explained by the higher propensity of the mothers to have been in part-time rather than full-time paid work while that child was growing up, and the consequent lack of wage progression,’ said the 2019 study, highlighting what the authors called ‘the long-term depressing effect’ of part-time work.14

At Harvard, the economist Professor Claudia Goldin has examined the way different jobs are structured in order to see how this sort of pay penalty might be addressed. She’s pointed to how some occupations – including within business, finance and the law – generally pay a premium for longer hours. A lawyer expected to be readily available for clients and working sixty hours per week, for example, is likely to earn more than double the salary of a comparable colleague working thirty hours a week. Professor Goldin says this ‘non-linearity’ arises when the job is set up or has historically been done in a way that makes it difficult for workers to substitute for one another. Within this environment, those who work shorter hours will suffer a disproportionate wage penalty.

She contrasts that with what has happened in the United States with pharmacists, a high-income profession in which women are well represented. In the 1970s the sector was dominated by small independent businesses, with many self-employed pharmacists, but today the majority are employees of large companies or hospitals. Part-time working is common, but pay tends to be perfectly in line with the number of hours worked – those who do fewer hours are paid proportionately less. Goldin attributes this to the ease with which pharmacists are able to substitute for one another – no single person is required to be available for an extended number of hours or for certain hours of the day. ‘The spread of vast information systems and the standardisation of drugs have enhanced their ability to seamlessly hand off clients and be good substitutes for one another. The result is that short and irregular hours are not penalised.’15

Professor Goldin says this structure helps to make it worthwhile for women to stay in paid work rather than leave to care for families, and that other professions could learn from the example of pharmacy. There will still be roles where employees won’t easily be able to swap in for each other – the founder of a business perhaps, or someone with unique and non-replicable expertise – but these should be fewer than is the case at present.

Sometimes internal reward systems are worth re-evaluating, especially if they have been in place for years. When a BBC investigation showed that 95 out of the 100 highest-paid hospital consultants in England were male, bonuses for clinical excellence, accumulating over time, turned out to be a considerable factor.16 One consultant, Mahnaz Hashmi, told me what applying for the bonuses involves: ‘You have to fill out a lengthy form within a short time-frame of a few weeks, showcasing your achievements and providing evidence for them. If you are part-time you will have less to put down. In the early stages it feels like a lot of effort for relatively small bonuses, but they become more valuable as they accumulate over the years.’

This NHS process was based around consultants putting themselves forward. ‘Women seem to do this less,’ she says. It also demanded a lot of the doctor’s own time – for example serving on awards committees, thereby making sure they were up to date with the latest criteria and scoring. ‘It’s difficult to do when you are part-time, and if you come back to full-time you usually find there’s already a wide salary differential between men and women consultants.’ My BBC colleague Nick Triggle says he was struck when working on the data by the self-perpetuating nature of the system. ‘Those working in the NHS told me younger consultants often only go for the awards after prompting from older ones, and there was a sense that senior figures are more likely to do this for those who remind them of their younger selves,’ he says. ‘The culture created, perhaps unconsciously, is one where men encourage other men towards the pay awards.’

In the summer of 2017, my own workplace was the setting for what turned out to be a lengthy row sparked by the BBC disclosing the salaries of the highest-earning on-air ‘talent’ – including presenters, contributors and actors – paid directly from the licence fee.17 The list, which included me, generated intense interest and comment: few people from ethnic minorities were among the ninety-six names, while people who went to private schools were over-represented, compared to the population as a whole.18 Most of the scrutiny, however, was focused on gender – the top seven earners were all male, and in some cases, there was a marked difference between the salaries of women and men appearing on the same programmes. The leading businessman Sir Philip Hampton, chairman of the drugs giant GSK, wondered why women broadcasters had let it happen. ‘How has this arisen at the BBC that these intelligent, high-powered, sometimes formidable women have sat in this situation?’19

The answer is that we didn’t know what the situation was until the disclosure. It sparked unprecedented conversations between colleagues, with women and men starting to share information about their salaries and, in some cases, their efforts to be paid equally to their peers. Some were in pay brackets that put them above the national average, others were not. And we wondered: if the system wasn’t treating women with agency and clout equally to men, what did that say about what might be happening to women elsewhere?

It’s happened even in companies which were sure their ethos would have guarded against any question of unequal pay. In 2015, the chief executive of the tech company Salesforce, Marc Benioff, was approached by his human resources chief about conducting an equal pay audit for its thirty thousand employees. Benioff thought it unnecessary, telling CBS News later that his company had a great culture: ‘We don’t play shenanigans paying people unequally. It’s unheard of.’ Yet he agreed to the audit, which went on to reveal not a few isolated cases but a persistent pay gap between men and women doing the same job. ‘It was through the whole company,’ said Benioff. ‘Every division, every department, every geography.’ Salesforce ended up giving 10 per cent of its female employees pay rises, but when it conducted another audit, the results showed that further adjustments were needed. ‘It turned out we had bought about two dozen companies. And guess what? When you buy a company you also buy its pay practices.’ Benioff concluded that there was a much bigger issue afoot. ‘I think it’s happening everywhere. There’s a cultural phenomenon where women are paid less.’20

Not everyone agrees with that, instead emphasising choice and its implications – for example, women deciding against pursuing time-intensive but financially rewarding career paths.21 But in Iceland, the government is placing a legal obligation on any employer of more than twenty-five people to undertake a similar exercise to Salesforce’s – a comprehensive assessment allowing them to be certified as paying equal wages for work of equal value. The process requires individual jobs to be analysed and scored against a list of criteria, including education required, level of responsibility, how demanding the role is and its value to the employer. The scores across the company or organisation are then compared and any gap between two jobs with the same score but different pay must be addressed. When Iceland’s Directorate of Customs piloted the system, the results included the role of statistics analyst being judged equal to that of a legal adviser, which had previously been higher paid. The statistics analysts were given a rise. The head of human resources, Unnur Kristjánsdóttir, said there was a wider dividend too: ‘We have a happier workforce, knowing that the salary system is something they can trust.’22

The new focus on gender is adding an urgency to questions being asked in many different settings including at two of the world’s top universities. Both Oxford and Cambridge have been puzzling over a gender gap at the highest levels of attainment – first-class degrees in some subjects. In 2014, Cambridge’s results in history showed that in the first part of the degree course, 88 per cent of the firsts went to male students, despite there being near equal numbers of men and women enrolled.23 At Oxford that year, 35 per cent of men but only 21 per cent of women studying English gained a first-class degree and there has been a persistent gender attainment gap in chemistry, too.24

At both universities, all students would have entered with excellent exam grades, and the effort to understand the gaps is made more complex by the range of subjects involved: from the essay-based humanities, where marking is more subjective, to the exactitude required in the sciences. At Oxford, Pro-Vice-Chancellor and Advocate for Diversity Rebecca Surender told me they have been looking at everything from pre-university education to the admissions process, exposure to female role models and the style of teaching, for example the often intense interaction in weekly tutorials. ‘The kind of degree you get matters and we don’t want women to be disadvantaged when they leave us and go into the world,’ she says. ‘Preliminary results suggest that there is no single explanation but rather a set of interactions between wider socialisation and what happens before women get to us, together with some environmental factors in the institution.’

At Cambridge one study investigated the relationship between exam structure and performance. Academics in the physics department set up a mock exam for first-year undergraduates in which, for some questions, the usual format was replaced with a ‘scaffolded’ version, broken down into sections showing the marks available for each.25 This style is closer to what those undergraduates would have been accustomed to in their school-leaving exams, and while it resulted in improved performance for all candidates, the women benefited more than the men. On average their marks increased by more than 13 per cent compared with their previous exam performance – while for the men the average increase was 9 per cent.

Dame Athene Donald, one of Cambridge’s most senior female professors and a physicist herself, told me a close focus on the beginning of the university experience was vital: ‘If women come here and struggle in their first year, they may never gain the confidence to proceed. In a subject like physics, where the percentage of girls is only 20–25, and you will be conscious at some level of being in a minority, it can feel even more threatening. Sometimes young women don’t like to say “I’m struggling” because they think that’s an admission of failure, so they struggle in silence.’

She wonders about the impact of stereotypes – perhaps young women don’t expect to do well in a mathematics-heavy subject such as physics – but also why more progress hasn’t been made since her own days as an undergraduate at the university. ‘In my final year class there were eight women out of about 100. But one didn’t expect anything else. I knew perfectly well that there were only three colleges that could admit women. What I find shocking today is that despite all the changes, despite the fact that we are fully co-educational apart from three women’s colleges, we still have these issues.’

At Oxford, one of the studies overseen by Rebecca Surender has focused on academic self-concept, or the belief in your ability to succeed in a particular subject area. Given that this tends to correlate with academic achievement, the aim was to establish any differences between men and women on arrival at the university and how their academic self-concept might change during the first year of study. She told me the findings showed that from the beginning of their course, male students had a higher perception of their own competence in their subject compared with their female peers, but for both sexes the level remained stable over the course of the academic year.

For the university this is of course a welcome finding because it suggests that the difference exists before students arrive. I do wonder, however, if there might also be an impact from the history, tradition and sense of excellence honed over centuries that surrounds you in these environments. I certainly remember times when I found Cambridge intimidating. The Times journalist Sathnam Sanghera, who was born into a working-class Sikh family and went on to read English at Cambridge, remembers ‘negative feelings of unbelonging’ while he was there.26 If academic self-concept is the key, how much might it be affected in people who have a nagging sense that they don’t quite fit or fully deserve to be in such a celebrated place?

In one study, researchers used a different university environment to investigate how peer perception and gender might influence students’ assessments of each other. Sarah Eddy and Daniel Grunspan asked biology undergraduates to complete surveys, getting them to highlight peers they felt were particularly strong in their grasp of the material studied and those they thought would do well on the course.

The results showed that male students were much more likely to rate other men as knowledgeable, a tendency that lasted throughout the academic year and persisted even after controlling for class performance and outspokenness. Female students showed no gender bias, nominating both fellow female and male students. The authors also found that there were some students who stood out in the eyes of their peers and were nominated multiple times, and that these students were always male. It wasn’t as though there weren’t women with similarly high grades in their classes, who also spoke up frequently and demonstrated their knowledge, but somehow they never gained the same ‘celebrity status’ as their male counterparts.27

When I read this study I started to imagine what the scene in the classroom might have looked like. The ‘celebrity’ students would no doubt have been aware of attracting their peers’ attention when they spoke – heads would have turned to listen to them, perhaps nodding in agreement. It’s a good experience to have, one that’s certain to make you feel more at ease, happier with your command of the subject material and probably spurred on to make further points. Could these apparently small interactions build up and develop capacity in a subject so much so that attainment is higher – or the chances of further study or a career in the field are increased? I started to think more and more about expectations of behaviour – whether in a classroom, smaller tutorial-style gatherings of students, or the first day in a new job. If we grow up with assumptions, even ones of which we are barely conscious, that men will speak first or take the lead, that can easily turn into a pattern that validates and reinforces those assumptions.

Consider this alongside evidence on discrimination within the workplace or before people even get there. One meta-analysis of studies conducted in OECD countries over a twenty-five-year period found that discrimination against ethnic minority applicants in the hiring process was commonplace.28 In 2009, research commissioned by the UK government reported high levels of name-based discrimination when researchers sent out multiple applications for real-life openings. The main difference between the applications was the likely ethnicity associated with their name: ‘Andrew Clarke’ was used to denote a white British male; ‘Mariam Namagembe’ for a black African female and ‘Nazia Mahmood’ for a Pakistani or Bangladeshi female. White names were favoured over equivalent applications from ethnic minority candidates.29

More recently, big data analayses have been used to look at information about individuals in new ways. The US-based neuroscientist and artificial intelligence expert Vivienne Ming took a vast data set of millions of real-life professional profiles collected by a tech recruitment firm and used them to compare the career trajectories of software developers whose first names were either ‘Joe’ or ‘Jose’. She found that those named ‘Jose’ typically needed a Master’s degree or more to be equally likely to get a promotion as a ‘Joe’ who had no degree. She called this a ‘tax on being different’, because of the extra costs and time involved in gaining the higher qualifications.