Through Three Campaigns: A Story of Chitral, Tirah and Ashanti

"Then the wonder that we felt about you ceased. It seemed for a moment impossible, for I had seen you go off with the sick convoy. Then it seemed to me that it was just the thing that Captain Bullen's son might be expected to do. You would naturally want to see fighting, but I did wonder how you managed to come back and get enlisted into the regiment. I remember, now, that I wondered a little the first night you joined. You were in uniform and, as a rule, recruits don't go into uniform for some time after they have joined. It was therefore remarkable that you should turn up in uniform, rifle and all."

"It was the uniform of the original Mutteh Ghar," Lisle said. "My servant had managed to get it; and the story that I was the man's cousin, and was therefore permitted to take his place, was natural enough to pass."

"But some of our officers must have helped you, sahib?"

"Well, I won't say anything about that. I did manage to join in the way I wanted, and you and your comrade were both very kind to me."

"That was natural enough, sahib. You were a young recruit, and we understood that you were put with us two old soldiers in order that we might teach you your duty. It was not long, however, before we found that there was very little teaching necessary for, at the end of a week, you knew your work as well as any man in the regiment. We thought you a wonder, but we kept our thoughts to ourselves.

"Now that we know who you are, all the regiment is proud that your father's son has come among us, and shared our lot down to the smallest detail. I noticed that you were rather clumsy with your cooking, but even in that respect you soon learned how things should be done.

"I suppose, sahib, we shall lose you at the end of the campaign?"

"Yes; I shall have to start for England, at once; for in order to gain a commission, I must study hard for two or three years. Of course, I shall then have to declare myself to the officers, in order to get my discharge. I am afraid that the colonel will be very angry, but I cannot help that. I am quite sure, however, that he will let me go, as soon as he knows who I am. It will be rather fun to see the surprise of the officers."

"I don't think the colonel will be angry, sahib. He might have been, if you had not done so well; but as it is, he cannot but be pleased that Captain Bullen's son should have so distinguished himself, even in the 32nd Pioneers, who have the reputation of being one of the best fighting regiments in all India."

"Well, I hope so, Pertusal. At any rate, I am extremely glad I came. I have seen what fighting is, and that under the most severe conditions. I have proved to myself that I can bear hardships without flinching; and I shall certainly be proud, all my life, that I have been one in the column for the relief of Chitral–that is to say, if we are the first."

"We shall be the first," the soldier said, positively. "It is hard work enough getting our baggage over the passes; but it will be harder still for the Peshawar force, encumbered with such a train as they will have to take with them.

"Ah! Sahib, if only our food were so condensed that we could carry a supply for twelve days about us, what would we not be able to do? We could rout the fiercest tribe on the frontier, without difficulty. We could march about fifteen or twenty miles a day, and more than that, if necessary. We could do wonders, indeed."

"I am afraid we shall never discover that," Lisle said. "The German soldiers do indeed carry condensed meat in sausages, and can take three or four days' supplies with them; but we have not yet discovered anything like food of which men could carry twelve days' supply. We may some day be able to do it but, even if it weighed but a pound a day, it would add heavily to the load to be carried."

"No one would mind that," Pertusal said. "Think what a comfort it would be, if we could make our breakfast before starting, eat a little in the middle of the day, and be sure of supper directly we got into camp; instead of having to wait hours and hours, and perhaps till the next morning, before the baggage train arrived. I would willingly carry double my present load, if I felt sure that I would gain that advantage. I know that the officers have tins of condensed milk, one of which can make more than a gallon; and that they carry cocoa, and other things, of which a little goes a long way. Now, if they could condense rice and ghee like that, we should be able to carry all that is necessary with us for twelve days. Mutton we could always get on a campaign, for the enemy's flocks are at our disposal; and it must be a bare place, indeed, where we could not find enough meat to keep us going. It is against our religion to eat beef, but few of us would hesitate to do so, on a campaign; and oxen are even more common than sheep.

"It is very little baggage we should have to take with us, then. Twenty ponies would carry sufficient for the regiment; and if government did but buy us good mules, we could always rely upon getting them into camp before dark. See what an advantage that would be! Ten men would do for the escort; whereas, at present, a hundred is not sufficient."

"Well, I wish it could be so," Lisle said. "But although some articles of food might be compressed, I don't think we should ever be able to compress rice or ghee. A handful of rice, when it is boiled, makes enough for a meal; and I don't imagine that it could possibly be condensed more than that."

"Well, it is getting late, and we march at daylight. Fortunately we have not to undress, but have only to turn in as we are."

Chapter 4: In The Passes

The march after leaving Dahimol was a short one. Here they were met by the governor of the upper parts of the valley, and he gave them very useful details of the state of parties in Chitral, and of the roads they would have to follow. He accompanied the force on the next day's march, and billeted all the troops in the villages; for which they were thankful enough, for they were now getting pretty high up in the hills, and the nights were decidedly cold.

They were now crossing a serious pass, and had reached the snow line; and the troops put on the goggles they had brought with them to protect their eyes from the dazzling glare of the snow. At two o'clock they reached the post at Ghizr, which was held by a body of Kashmir sappers and miners. The place had been fortified, and surrounded by a strong zereba. The troops were billeted in the neighbouring houses, and they halted for a day, in order to allow the second detachment of the Pioneers and the guns to come up. Here, also, they were joined by a hundred men of the native levies.

When they prepared for the start, the next morning, they found that a hundred of the coolies had bolted during the night. Two officers were despatched to find and fetch them back. Fifty were fortunately discovered, in a village not far off, and with these and some country ponies the force started. They passed up the valley and came upon a narrow plain. Here the snow was waist deep, and the men were forced to move in single file, the leaders changing places every hundred yards or so.

At last they came to a stop. The gun mules sank to their girths in the snow and, even then, were unable to obtain a footing. Men were sent out to try the depth of the snow on both sides of the valley, but they found no improvement. Obviously it was absolutely impossible for the mules and ponies to get farther over the snow, in its present state. It was already three o'clock in the afternoon, and only eight miles had been covered. The force therefore retired to the last village in the valley. Two hundred Pioneers under Borradaile, the sappers, and the Hunza levies were left here, with all the coolie transport.

Borradaile's orders were to force his way across the pass, next day; and entrench himself at Laspur, the first village on the other side. He was then to send back the coolies, in order that the remainder of the force might follow. With immense trouble and difficulty, the kits of the party that were to proceed were sorted out from the rest, the ammunition was divided and, at seven o'clock, the troops who were to return to Ghizr started on their cold march. They reached their destination after having been on foot some fifteen hours.

Lisle was with the advance party. They were all told off to houses in the little village. Fires were lighted and the weary men cooked their food and, huddling close together, and keeping the fires alight, slept in some sort of comfort. Next morning at daybreak they turned out and found, to their disgust, that the snow was coming down heavily, and that the difficulties would be even greater than on the previous day. Borradaile therefore sent back one of the levies, with a letter saying that it was impossible to advance; but that if the sky cleared, he would start on the following morning.

The Kashmir troops at Ghizr volunteered to go forward, and make a rush through the snow; and Stewart and his lieutenant, Gough, set out with fifty of them, taking with them half a dozen sledges that had been made out of boxes. On arriving at Tern, Stewart found fodder enough for the mules, and begged that the guns might be sent up. Borradaile had started early; and Stewart with the fifty Kashmir troops followed, staggering along dragging the guns and ammunition. The snow had ceased, but there was a bitter wind, and the glare from the newly-fallen snow was terrible.

The guns, wheels, and ammunition had been told off to different squads, who were relieved every fifty yards. In spite of the cold, the men were pouring with perspiration. At one point in the march a stream had to be crossed. This was done only with great difficulty, and the rear guard did not reach the camping ground, at the mouth of the Shandur Pass, until eleven at night; and even then the guns had to be left a mile behind. Then the weary men had to cut fuel to light fires. Many of them were too exhausted to attempt to cook food, and at once went to sleep round the fires.

Early the next morning, the Pioneers and levies started to cross the pass. The Kashmir men brought up the guns into camp but, though the distance was short, the work took them the best part of the day. The march was not more than ten miles; but Borradaile's party, though they left Langar at daylight, did not reach Laspur till seven o'clock at night. The slope over the pass was a gradual one, and it was the depth of the snow, alone, that caused so much delay. The men suffered greatly from thirst, but refused to eat the snow, having a fixed belief that, if they did so, it would bring on violent illness.

On arriving at the top of the pass, the Hunza levies skirmished ahead. So unexpected was their arrival that the inhabitants of the village were all caught and, naturally, they expressed their extreme delight at this visit, and said that they would be glad to help us in any way. They were taken at their word, and sent back to bring up the guns. Their surprise was not feigned, for the Chitralis were convinced that it would be impossible to cross the pass, and letters were found stating that the British force was lying at Ghizr.

The feat, indeed, was a splendid one. Some two hundred and fifty men, Hindoos and Mussulmans had, at the worst time of the year, brought two mountain guns, with their carriages and ammunition, across a pass which was blocked for some twenty miles by deep, soft snow; at the same time carrying their own rifles, eighty rounds of ammunition, and heavy sheepskin coats. They had slept for two nights on the snow and, from dawn till dark, had been at work to the waist at every step, suffering acutely from the blinding glare and the bitter wind. Stewart and Gough had both taken their turns in carrying the guns, and both gave their snow glasses to sepoys who were without them.

Borradaile's first step was to put the place in a state of defence, and collect supplies and coolies. In the evening the guns were brought in by the Kashmir troops, who were loudly cheered by the Pioneers.

Lisle had borne his share in the hardships and had done so bravely, making light of the difficulties and cheering his comrades by his jokes. He had escaped the thirst which had been felt by so many, and was one of those who volunteered to assist in erecting defences, on the evening of their arrival at Laspur.

At two o'clock the next day, the rest of the force came into camp. A reconnoitring party went out and, three miles ahead, came upon the campfires of the enemy. They were seen, three miles farther down the valley, engaged in building sangars; but as the force consisted of only one hundred and fifty men, it was not thought advisable to attack, and the troops consequently returned to camp.

The next day was spent in making all the arrangements for the advance. Messengers were sent out to all the villages, calling on the men to come in and make their submission. This they did, at the same time bringing in supplies and, by night, a sufficient number of native coolies had been secured to carry all the baggage, including ammunition and guns.

A native chief came in with a levy of ninety native coolies. These were found most valuable, both in the work and in obtaining information. From their knowledge of the habits of the people, they were able to discover where the natives had hidden their supplies; which was generally in the most unlikely places.

The reconnoitring party had found that, some six miles on, the snow ceased; and all looked forward with delight to the change. A small garrison of about a hundred, principally levies, were left at Laspur; with instructions to come on when the second party arrived. The main force started at nine o'clock.

At Rahman the snow was left behind. Here they learned that the enemy would certainly fight, between the next village and Mastuj. Lieutenant Beynon went on with a party of levies and gained a hill, from which he could view the whole of the enemy's position. Here he could, with the aid of his glasses, count the men in each sangar, and make out the paths leading up the cliffs from the river. When he had concluded his observations, he returned and reported to Colonel Kelly; and orders were issued for the attack, the next day.

The levies were expected to join the next morning. They were to advance with a guide, and turn out the enemy from the top of a dangerous shoot; from which they would be enabled to hurl down rocks upon the main body, as it advanced. Beynon was to start, at six, to work through the hills to the right rear of the enemy's position. The main body were to move forward at nine o'clock.

Beynon encountered enormous difficulties and, in many places, he and his men had to go on all fours to get along. He succeeded, however, in driving off the enemy; who occupied a number of sangars on the hills, and who could have greatly harassed the main body by rolling down rocks upon them.

The enemy's principal position consisted of sangars blocking the roads to the river, up to a fan-shaped alluvial piece of ground. The road led across this ground to the foot of a steep shoot, within five hundred yards of sangars on the opposite side of the river and, as it was totally devoid of any sort of shelter, it could be swept by avalanches of stones, by a few men placed on the heights for the purpose.

When the troops arrived within eight hundred yards, volley firing was opened; and the guns threw shells on the sangar on the extreme right of the enemy's position. The enemy were soon seen leaving it, and the fire was then directed on the next place, with the same result. Meanwhile Beynon had driven down those of the enemy who were posted on the hill; and general panic set in, the guns pouring shrapnel into them until they were beyond range.

The action was over in an hour after the firing of the first shot. The losses on our side were only one man severely, and three slightly wounded. After a short rest, the force again proceeded, and halted at a small village a mile and a half in advance. A ford was found, and the column again started. Presently they met a portion of the garrison who, finding the besieging force moving away, came out to see the reason.

In the meantime, the baggage column was being fiercely attacked; and an officer rode up, with the order that the 4th company were to go back to their assistance. The company was standing in reserve, eager to go forward to join in the fight and, without delay, they now went off at the double.

They were badly wanted. The baggage was struggling up the last kotal that the troops had passed, and the rear guard were engaged in a fierce fight with a great number of the enemy; some of whom were posted on a rise, while others came down so boldly that the struggle was sometimes hand to hand. When the 4th company reached the scene, they were at once scattered along the line of baggage.

For a time the enemy fell back but, seeing that the reinforcement was not a strong one, they were emboldened to attack again. Their assaults were repulsed with loss, but the column suffered severely from the fire on the heights.

"We must stop here," the officer in command said, "or we shall not get the baggage through before nightfall; and then they would have us pretty well at their mercy. The Punjabis must go up and clear the enemy off the hill, till the baggage has got through."

The Punjabis were soon gathered and, led by an English officer, they advanced up the hill at a running pace, until they came to a point so precipitous that they were sheltered from the enemy's fire. Here they were halted for a couple of minutes to gain breath, and then the order was given to climb the precipitous hill, which was some seventy feet high.

It was desperate work, for there were points so steep that the men were obliged to help each other up. Happily they were in shelter until they got to within twenty feet of its summit, the intervening distance being a steep slope. At this point they waited until the whole party had come up; and then, with a cheer, dashed up the slope.

The effect was instantaneous. The enemy, though outnumbering them by five to one, could not for a moment withstand the line of glittering bayonets; and fled precipitately, receiving volley after volley from the Pioneers. As the situation was commanded by still higher slopes, the men were at once ordered to form a breastwork, from the stones that were lying about thickly. After a quarter of an hour's severe work, this was raised to a height of three feet, which was sufficient to enable the men to lie down in safety.

By the time the work was done, the enemy were again firing heavily, at a distance of four hundred yards, their bullets pattering against the stones. The Punjabis, however, did not return the fire but, turning round, directed their attention to the enemy on the other side of the valley, who were also in considerable force.

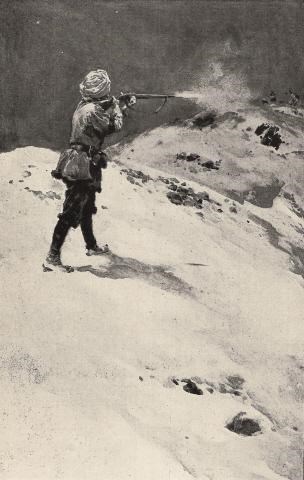

"Here!" the officer said to Lisle, "do you think you can pick off that fellow in the white burnoose? He is evidently an important leader, and it is through his efforts that the enemy continues to make such fierce attacks."

"I will try, sir," Lisle replied in Punjabi; "but I take it that the range must be from nine hundred to a thousand yards, which is a long distance for a shot at a single man."

Lying down at full length, he carefully aimed and fired. The officer was watching through his field glass.

"That was a good shot," he said. "You missed the man, but you killed a fellow closely following him. Lower your back sight a trifle, and try again."

The next shot also missed, but the third was correctly aimed, and the Pathan dropped to the ground. Some of his men at once carried off his body. His fall created much dismay; and as, at that moment, the whole of the Punjabis began to pepper his followers with volley firing, they lost heart and quickly retired up the hill.

"Put up your sights to twelve hundred yards," the officer said. "You must drive them higher up, if you can; for they do us as much harm, firing from there, as they would lower down. Fire independently. Don't hurry, but take good aim.

"That was a fine shot of yours, Mutteh Ghar," he said to Lisle, by whose side he was still standing; for they had gone so far down the slope that they were sheltered from the fire behind. "But for his fall, the baggage guard would have had to fight hard, for he was evidently inciting his men to make a combined rush. His fall, however, took the steam out of them altogether. How came you to be such a good shot?"

"My father was fond of shooting," Lisle said, "and I used often to go out with him."

"Well, you benefited by his teaching, anyhow," the officer said. "I doubt if there is any man in the regiment who could have picked off that fellow, at such a distance, in three shots. That has really been the turning point of the day.

"See, the baggage is moving on again. In another hour they will be all through.

"Now, lads, turn your attention to those fellows on the hill behind. As we have not been firing at them for some time, they will probably think we are short of ammunition. Let us show them that our pouches are still pretty full! We must drive them farther away for, if we do not, we shall get it hot when we go down to join the rear guard. Begin with a volley, and then continue with independent firing, at four hundred yards."

The tribesmen were standing up against the skyline.

"Now, be careful. At this distance, everyone ought to bring down his man."

Although that was not accomplished, a number of men were seen to fall, and the rest retired out of sight. Presently heads appeared, as the more resolute crawled back to the edge of the crest; and a regular duel now ensued. Four hundred yards is a short range with a Martini rifle, and it was not long before the Punjabis proved that they were at least as good shots as the tribesmen. They had the advantage, too, of the breastwork behind which to load, and had only to lift their heads to fire; whereas the Pathans were obliged to load as they lay.

Presently the firing ceased, but the many black heads dotting the edge of the crest testified to the accurate aim of the troops. The tribesmen, seeing that their friends on the other side of the valley had withdrawn, and finding that their own fire did not avail to drive their assailants back, had at last moved off.

For half an hour the Pioneers lay, watching the progress of the baggage and, when the last animal was seen to pass, they retired, taking up their position behind the rear guard. The column arrived in camp just as night fell.

"That young Bullen can shoot," the officer who commanded the company said, that evening, as the officers gathered round their fire. "When, as I told you, we had driven off the fellows on the right of the valley, things were looking bad on the left, where a chief in a white burnoose was working up a strong force to make a rush. I put young Bullen on to pick him off. The range was about nine hundred and fifty yards. His first shot went behind the chief. I did not see where the next shot struck, but I have no doubt it was close to him. Anyhow, the third rolled him over. I call that splendid shooting, especially as it was from a height, which makes it much more difficult to judge distance.

"The chief's fall took all the pluck out of the tribesmen and, as we opened upon them in volleys, they soon went to the right about. We peppered them all the way up the hill and, as I could see from my glasses, killed a good many of them. However, it took all the fight out of them, and they made no fresh attempt to harass the column."

"The young fellow was a first-rate shot," the colonel said. "If you remember he carried off several prizes, and certainly shot better than most of us; though there were one or two of the men who were his match. You did not speak to him in English, I hope, Villiers?"

"No, no, colonel. You said that he was to go on as if we did not know him, till we reached Chitral; and of course spoke to him in Punjabi.

"One thing is certain: if he had not brought down that chief, the enemy would have been among the baggage in a minute or two; so his shot was really the turning point of the fight."

"I will make him a present of twenty rupees, in the morning," the colonel said. "That is what I should have given to any sepoy who made so useful a shot, and it will be rather fun to see how he takes it."