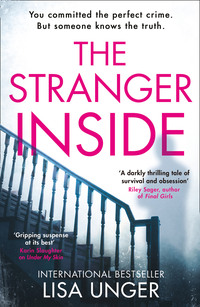

The Stranger Inside

“I don’t know,” she’d said tightly.

It was one of those loaded moments, air simmering with all the things each of them wanted to say but didn’t. Instead, he’d pressed his mouth into a line—he claimed that expression meant frustration, she read it as disapproval—gave a quick nod, left the room. After some time seething, she’d unlatched the baby, placed her gently in the crib.

How much longer? she’d thought. What kind of question is that?

“I want you back,” he’d said at the table, gentle. He touched her hand. He wasn’t a jerk, was he? One of those clueless men who thought her body existed for his pleasure only. “We said six months.”

“I want me back, too,” she admitted.

She wanted to nurse Lily, loved the closeness of it, those soothing quiet moments with her baby. She wanted her body back, wanted to feel sexy again. It seemed everything about motherhood was this complicated twist of emotion, a delicate balance of holding on and letting go.

And, seriously, those nursing bras? Some of them were cute, but for the most part they looked like pieces of equipment rather than lingerie. She hadn’t felt sexy in ages. How could you be sexy, hot, erotic when you didn’t even own yourself?

“So,” he’d said at dinner that night. “Can we get on a plan?”

Thanks to a Google search—how to wean your baby!—she was on a plan. The morning and midday feedings were solid food now. Which meant she could have a glass of wine at night and not have to “pump and dump” (another sexy bit of breastfeeding terminology). The pediatrician said so. Anyway, she’d vowed never to put that pump back on her breast again. God, how much more like a cow could a thing make you feel?

She could already feel that she was producing less milk. Her breasts were smaller, more familiar. She’d bought some new lingerie, lacy, pretty, no cup clasps in sight. Sexy? She wasn’t feeling it yet. But she was getting there.

She drained the vegetables, milled them into mush, then filled the little jars.

Very sexy.

She liked the way they looked with their cheerful blue tops lined up in the fridge, which was stocked and tidy. Everything in order, everything sorted. There was a satisfaction in it. She ran the house with a frugal, high-end, minimalist zeal. She did the grocery shopping, cooking and day-to-day cleaning. The cleaning lady came once every other week to do the big stuff. She did a load of laundry every day. The dry cleaning, mainly Greg’s work clothes, got picked up on Tuesdays and Thursdays. She ran the house the way she used to do her job—with accuracy and efficiency.

She was only half listening to the news broadcasting from her phone as she wiped down the quartz countertop, though it was already clean. The news was bad, as usual. She tried not to get hooked in as she managed the fresh tulips that dipped from their glass vase, pulling a wilting one, adding more water. On the distressed gray cabinet, she spied a sticky handprint. She wiped it clean. The sun was streaming through the big windows now. She put some of Lily’s toys in the wicker basket, rearranged the fluffy white throw on the cozy sectional where she and Greg spent most of their time now that they were parents—who knew you could watch so much television.

“—Markham, tried and acquitted for the violent murder of his pregnant wife, Laney Markham, was found dead in his home early this morning.”

The words stopped her cold, a board book clutched in her hand. She moved over to her phone, turned up the volume, something other than caffeine pulsing through her system.

The voice was familiar, and not just because Rain listened to this National News Radio broadcast every day, but because the woman speaking was her closest friend and former colleague. And the news show was the one Rain used to write, edit and produce.

“Markham was found not guilty last year in the stabbing death of his wife. His defense leaned heavily on cell phone records that confirmed his alibi that at the time of his wife’s murder, he was out of state with a woman who turned out to be his lover.

“Police are investigating. This is Gillian Murray reporting, National News Radio.”

She could almost hear the lick of glee in her friend’s voice. The two of them had covered the story together for over a year, were both crushed when Markham been acquitted. No one else had ever been charged with Laney Markham’s murder, and the murder of her unborn child.

It had stayed with them both, the terrible injustice of it nagging at them. They looked on with impotent rage as the machine took over—Markham’s inevitable book release, the talk show circuit where he pretended to be tirelessly looking for his wife’s killer. They had to see his face nearly every day, the mask of the wrongly accused man so fake, so painted on, Rain couldn’t see how anyone might believe it.

I used to believe in justice, Gillian said one night over too many drinks. I don’t anymore. Bad people win. They win all the time.

Rain had tried to cheer her up, but how could she? Her friend was right.

She snapped off the broadcast, stared at the jars of baby food. The room swirled around her the way it used to, when a story got its teeth in her.

Someone killed Steve Markham. He got away with murder, until he didn’t. A million questions started to take form. Who, what, when, where? Why? It touched another nerve, too.

Greg came down the stairs, dressed in his workout clothes, holding a garment bag. He was watching her. From the lines of worry etched in his forehead, she could tell he already knew.

“You heard about Steve Markham?” she asked.

“Just got the news update on my phone,” he said, rubbing at the crown of his head. He put the garment bag on the couch, tried for a smile. “You and Gillian should get together and have a toast. Markham finally got what he deserved.”

“Who do you think did it?” she asked.

“You would know better than I do,” he said. His voice was gravelly, soft. She’d never heard him raise it, in all their years together. “The brother. The father. The guy had no shortage of enemies.”

“Lots of people make threats,” she said. “It’s another thing altogether to take someone’s life. Even someone who deserves it.”

She poured him a cup of coffee from the French press, handed him an apple. This was his preworkout breakfast. He’d put on weight during her pregnancy. But he’d lost it all. In fact, he was in better shape now than he had been when they were first dating, the muscles on his arms strong and defined, his body lean. She could not say the same for herself. She tried to squeeze herself into her old jeans the other day and wound up lying on the bed, crying. Had she ever fit into them? It seemed impossible.

“What are you thinking?” he asked. He wrapped her up, kissed her on the forehead. “What’s going on in that big brain of yours?”

“It’s just—odd,” she said. “A year later. Someone kills him.”

He moved away, took a bite of his apple, a sip of his coffee.

“It’s a good day when people get what they deserve. Isn’t it?” he said, moving toward the door. “One less psycho in the world.”

Why didn’t it feel like that? She was aware of a hollow pit in her stomach.

“I’m going to get a workout before I head in,” he said.

Oh, how nice for you, she thought but kept it to herself.

“Okay,” she said instead. “Do you think you’ll be back in time for me to work out tonight?”

There was a bit of an edge to all of it. Who stayed home? Who worked? Who had time to be with friends and indulge in hobbies? They both worked at giving each other time.

“I’ll try, honey,” he said. “But you know how it is, right? You can’t always just leave.”

Greg was the producer for the local television news program. Local news.

“Right,” she said. “There might be some breaking story about the sheep-shearing festival this weekend.”

He gave her a look. “Don’t be a news snob, babe. We can’t all cover major cases for the National News Radio, can we?”

He came back to where she stood in the kitchen, pulled her in again, this time for a kiss on the mouth.

She felt herself smile, light up a little. That’s one of the things she first loved about him, that he didn’t have the huge, hyperinflated ego of the other men she met in news. She could tease him, and he didn’t sulk. It didn’t always work in reverse, she’d be the first to admit.

“That was nice last night,” he said. “You look good, Rain. You feel good.”

“So do you,” she said. His lips on her neck, his hand on her back.

“I’ll get home,” he whispered. “I promise.”

He downed his coffee, then moved toward the door.

She followed him out to the car. Autumn crisp and cool on the air. A stiff wind bent the branches; she pulled her robe tight around her. Yes, she was the woman who went out into the driveway in her pajamas. So what?

Greg put his bag in the back, walked over to her and rested his hands on her shoulders. The shine of his deep brown eyes, the small scar on his chin, the wild brown hair that he couldn’t quite tame unless he cropped it short. She saw worry in the lines on his forehead, in the wiggle of his eyebrows.

“Don’t let this pull you under again, okay?”

She didn’t have to ask him what he meant. The Markham case. It had shaken her, rattled them. That person she was when a story was under her skin—she wasn’t a good wife, a good friend. In fact, she wasn’t good for anything except the story she wanted to tell.

That was then—another life, another woman. She had Lily now; she was a mother. There wasn’t room for both parts of herself. She was smart enough to know it.

Another kiss—soft and familiar, the scent of him so comforting—then he climbed into their sensible hybrid SUV and drove off. She watched him, his words echoing in her head.

Got what he deserved.

Her pulse raced a little, that early-morning nausea came back. She wanted to call Gillian but knew she wouldn’t be able to talk for a while yet.

As she stepped back into the foyer, Lily started crying. Game on.

But while Lily ate her oatmeal, secure in her high chair, Rain retrieved her laptop. She half expected the lid to groan like the door on an abandoned house, maybe find some cobwebs covering the keyboard. It had been a long time since she thought about work.

She opened the files she’d kept from the Markham case, and started rereading her old notes, sifting through the digital images, the saved internet links.

She used to dream about Steve Markham, and in her dreams, he had the cold yellow eyes of a wolf. They often, in her dreams, shared a meal across a long table, lined with plates of rotting food—overripe fruit split open, red, spilling innards and seeds on the white cloth, decomposing meat buzzing with flies, wilting greens turning to slime. He’d be laughing, teeth sharp. And though she wanted to run, she’d be lashed to her seat, staring, mesmerized by his hideous grin.

When he’d been acquitted, she fantasized about killing him herself.

But the rage passed, left a kind of emptiness in its wake. A terrible fatigue of the mind and the spirit.

She was remembering all of this when Lily tossed her sippy cup onto the table in front of the laptop.

“Ma! Ma!” Lily yelled happily, looking very pleased with herself.

Rain gazed over the computer at her daughter, apple cheeks and tangle of hair, face and bib painted with oatmeal.

“You’re right, bunny,” she said, snapping the lid on her laptop closed and lifting the pink cup. “Let it go.”

TWO

But she couldn’t let it go.

That was always her problem.

She could never just let things go.

That’s what made her a good reporter, and kind of shitty at everything else. A dog with a bone, in fact, according to her husband. She held grudges, which every shrink and life coach would tell you was bad for your marriage, your life. She did not meditate. She was not Zen, by any means. She did not go with the flow. She held on. Dug in deep.

Rain strapped Lily into the jogging stroller—because there was no way Greg was going to get home in time for her to go to the gym, however pure his intentions. Her fatigue from the too-early morning wake-up had lifted a little (thank you, three cups of coffee). Lily kicked her legs and waved her chubby arms with joy, cooing happily, resplendent in rainbow leggings and pink fleece.

At the end of the driveway, Rain surveyed the tree-lined street, as was her habit.

She looked for unfamiliar parked cars, strange lone figures loitering. Even here—where the sidewalk was always empty of strangers, where precious clapboard houses painted in muted grays and blues, eggshell or soft maroon, nestled in perfectly manicured lawns, where it seemed not even weeds were allowed to grow—she watched for him.

But no. Today there was just the neighbor’s mottled tabby delicately licking her paw on the stoop. Tasteful Halloween decorations hung on doors, a cornucopia, a smiley witch with glittery yarn for hair. Collections of painted jack-o’-lanterns on wooden porch steps. Nothing too creepy or scary, of course. Peaceful. Safe. Their street was a picture postcard of suburban bliss, the place where nothing bad ever happened. Until it did.

Then she was doing that thing she did where she took a peaceful scene and imagined it descending into chaos—a gang of thugs loping up the street smashing the windows of expensive cars, an earthquake splitting the street, a raging wildfire turning homes into ashy ruin. Or, her personal go-to, a hulking form moving from the dappled shadows under the oak. A shadow, waiting to destroy the pretty life she’d built with Greg. Yes, around every corner could be your worst nightmare. She knew that, better than most.

“Stop it,” she said to herself.

“Op it!” echoed Lily, giggling.

“Mommy’s a little crazy,” she told her daughter, who would no doubt figure it out for herself soon enough.

She put one earbud in, leaving the other to dangle so that she could hear the street noise and Lily. Listening to the news, she pushed them onto the sidewalk and started a light jog toward the running path. Dulcet voices droned about trade wars escalating, a rocket headed for Mars, fires burning out of control in California, the suicide of a beloved celebrity chef. Was the world really so dark? Shouldn’t there be a channel just for good news?

She tuned out a bit, listening instead to the sound of her own breath, eyes vigilant to their surroundings. She was hoping for more news on the Markham case when Gillian called.

“You heard,” said her old friend by way of greeting. That tone, taut with excitement, it stoked the fire in Rain.

“I heard you this morning,” she said. “What happened?”

“I don’t have all the details, but I called Chris.”

Christopher Wright, lead detective on the Markham case—and Gillian’s ex. Hot, hot, hot. But distant, too into the work. Fuckable, but not datable. Which, you know, could be okay. But it wasn’t okay for Gillian. She wanted the whole thing—the wedding, the baby, the house. Chris—he wasn’t that guy.

“He said—off the record—that it was bizarre.” Gillian leaned on the word.

“Oh?” Rain stopped at the light, kept jogging in place.

One of her neighbors drove by. Mitzi, the older lady from across the street, waved and smiled. Rain waved back. Mitzi had offered to do some babysitting. Now that Lily was older, Rain was considering it. Just an hour or two every other day so that she could get back into a real workout routine, think about maybe doing some freelancing. Money was tight-ish. But the real truth was, she missed working. She hadn’t admitted this to anyone yet.

“Something like this?” Gillian said. “You’ve gotta assume it’s Laney’s brother or her dad, finally making good on the threats they delivered in the courtroom. That’s the first thing you think. You expect a big mess. Overkill. Right?”

“Right.”

There it was. That tingle, that tension. In the business, they call it the belly of fire. That overwhelming urge to know, to get the story, to find the truth. She crossed the street, moved onto the path that circled the park. Of course, it was more than that for Rain.

“Wrong,” said Gillian. “Chris wouldn’t tell me much—very tight-lipped. He just said that the scene was ‘organized.’ He said, and I quote, ‘It was obviously planned and executed cleanly.’”

“What does that mean?”

“That’s all he’d tell me. Police are holding a press conference later today.”

Frustration. Nothing worse than the delay of information.

“Keep me in the loop.” But she wasn’t in the loop. She was so far out of it that she didn’t even exist anymore. Which, a year ago, was what she wanted. Wasn’t it?

“Of course,” Gillian said. Then a sigh. “Wish you were here.”

“Me, too,” she said. She meant it. And she didn’t. Complicated. Everything was so goddamn complicated.

“How’s our girl?” Gillian asked.

Gillian was the date-night sitter. Once a month or so, she came in from the city, stayed with Lily while Greg and Rain went out. Gillian slept in the guest room, and spent the next day with Rain and Lily, while Greg slept in or played golf or whatever, or vegged out in front of a game on television. It was the rare win-win-win scenario.

“She’s missing her auntie Gillian,” said Rain.

There was that pause. The pause Rain was guilty of herself, when you’re doing something else—checking your email, texting, surfing the web, whatever—and talking on the phone.

“Saturday, right?” Gillian said, plugging back in.

“Still good for you?”

“Wouldn’t miss it.”

“Bring details.”

“Deal.”

Rain circled the park a couple of times, thinking about what Gillian had said. The scene was organized. Obviously planned and cleanly executed. That was weird. Murder is a mess, especially a revenge killing. Rage usually isn’t careful; it doesn’t plan. It doesn’t clean up after itself. Usually.

Something niggled at the back of her brain, like she should be remembering something she couldn’t. But that was baby brain—sleep deprivation, hormones, nursing, constantly monitoring needs, plagued with worry, fear, overwhelmed by love, hours, days, months just disappearing. It was a fog you felt your way through.

Sweating, breathless, Rain found herself on the path that led to the playground, even though the last couple of times she stopped there after her run, she promised herself that she wouldn’t go back. The other moms who gathered there—they talked about strollers and pediatricians, tummy time, swaddling, milling organic baby food, and colic. Some talked about their husbands, apparently clueless buffoons who’d impregnated them and then continued with life as it was before, who still thought they might get laid every now and then. They talked about their single friends who had no idea.

Rain didn’t talk much—she listened. That was her gift, to keep her mouth shut and hear what other people were saying. That was the way of the news writer—observe, ask, listen, report. But she often left the group feeling anxious, eager to get home.

Still, Rain pulled the stroller up to one of the picnic tables as if drawn to the communal nature of the gathering in spite of herself. She gave Lily her sippy cup and retrieved her own water bottle. She put some Cheerios in the stroller tray—which she’d just cleaned, thank you very much. She’d gotten a look last time from one of the more tightly wound mommies in the playground group—what was her name? Gretchen. Aren’t you worried about germs? she’d gasped. She’d put her pretty, conspicuously ringed, gel-manicured hand to her chest in a gesture of dismay, her face a caricature of concern. Rain had fought back the unreasonable urge to punch her.

No. Rain was not worried about germs. She was a career news writer and producer, among other things. She was worried about lots and lots of things—North Korea, racism, the long-term fate of the #MeToo movement, the sex slave trade, global warming, letting go accidentally of that jogging stroller and watching it careen into traffic. And other things—lots of things imagined in vivid detail, Technicolor detail so bright that it could take her breath away. They had a state-of-the-art security system installed in their house, even though she knew—she knew—that the incident of stranger crime against children, home invasion and abduction was a statistical anomaly. She had very personal reasons for wanting that level of security. But, no, she was no germophobe. Was that a word?

Did you know, Rain answered Gretchen—a bit snippily, that normal exposure to germs helps your child’s immune system develop?

Emmy, one of the other playground mommies, had chimed in with a grave nod: Rain was a reporter. She worked for National Radio News. Gretchen had pretended to be distracted by her phone, unimpressed. Oh, really, Gretchen said absently, staring off at the playground. When was that?

Today, some of the mommies with older children gathered around the playground. Toddlers tended to hang out in the sandbox. Lily was just walking, more like cruising, so Rain didn’t always take her out of the stroller unless she got restless. She pushed over to the group, parked the stroller with the rest.

“How was your run?” sang Gretchen, casting her an unreadable look.

Funny how such an innocent question could have so many layers. Gretchen looked at her with a smile. Tight-bodied, tiny, with bright green eyes, a blond pixie cut, Gretchen had something icy beneath the surface, something sharp. Somehow Rain felt acutely aware of the size of her own thighs, the sweat on her shirt, her forehead. Gretchen looked positively dewy, her white shirt crisp, her skinny, skinny jeans faded perfectly. And that ring. Holy Christ. How many carats was that?

“You jogged here? Good for you,” said Emmy.

Emmy, mom to a six-month-old girl named Sage, used to work in book publishing, an editor who’d had a couple of bestselling authors to her credit. She still worked freelance from home.

Emmy’s thick auburn hair was pulled up into a high ponytail, eyes shining with intelligence. “I haven’t worked out in months. My boobs are huge.”

“Stop it. You’re gorgeous and you know it,” said Rain. She was—even in sweats, unshowered, a little spit-up on her hoodie. Her skin was peaches-and-cream perfect, hair shiny with health. When her little one started to cry, Emmy lifted the baby from her pram, then proceeded to whip her breast out right there in front of everyone.

Gretchen turned away, clearly embarrassed.

“Oh, what, you’ve never seen a boob before?” said Emmy. Her face lit up with mischievous glee.

“The kids,” said Gretchen.

“Oh, they’ve never seen one before?”

Emmy’s laugh was mellifluous, contagious, and Rain laughed, too.

“I’m done with that little shawl thing,” said Emmy. “I’m just whipping it out wherever now. You don’t like it? Look the other way.”

“I couldn’t nurse,” said Gretchen stiffly. “I have inverted nipples.”

“Inverted nipples? Ouch,” said Beck, joining the group.

Beck was the youngest mommy. Married to her high school sweetheart, with two toddlers (Tyler, two; Jessa, three and a half) at twenty-six, she had another one on the way. Rain thought of her as a career mom. The rest of them did something else first, or wanted to be something else, too. If Beck wanted anything else, she hadn’t mentioned it.

“Did you hear about that guy? The one who killed his wife last year?” asked Emmy. “Markham?”

Gretchen shook her head in distaste. “We don’t watch the news at home. Too stressful.”

“Someone killed him,” said Beck, voice low. Then, “About time.”

Lily started to fuss. Gretchen moved over quickly as if the baby was hers, lifting her from the stroller with a quick glance to Rain for permission. Rain nodded easily. It was funny, how natural certain things were with other moms—maybe it’s what kept her coming back to the group. There was something communal about the gathering, comforting. Someone always had wipes, or Cheerios, or was willing to bandage a knee, had a soothing word. Fraught in some ways, with a weird undercurrent of competitiveness, but definitely communal.