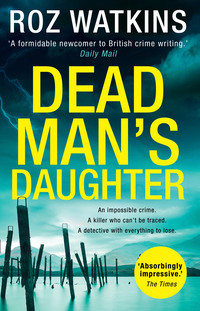

A DI Meg Dalton thriller

‘Sleeping pills. I can show you.’

A ten-year-old on pills. I knew in the US the drug companies had achieved the holy grail of pills for all – old or young, sick or well. But in this country, sleeping pills for a kid was unusual.

‘And . . . why did you realise something was badly wrong?’ I said. ‘When you saw my car, I mean. You seemed very upset and worried.’

Rachel turned her body away from me and spoke as if to someone sitting on her opposite side. ‘I just knew.’ She blew her nose again.

All the birdsong and rustling of the trees and the rushing river seemed far away. The woods were quiet around us, as if muted by the presence of the stone girls.

‘What’s the story behind the statues?’ I asked.

‘Oh, I don’t know. Some ancient folk tale or something. Phil was obsessed with them but he always denied it.’

‘I noticed a carving on your landing, similar to one of them.’

‘You see. Phil did that. I sometimes thought he only bought the house because of the statues. It’s such a money pit, I don’t know why else he came here. But he always clammed up if I asked him about them, apart from one time when he was drunk . . . ’

‘What did he say then?’

‘I couldn’t get much sense out of him. But something about doing penance, I think.’

My ears twitched. ‘Penance? What did he mean by that?’

‘He wouldn’t say. But it seemed to have something to do with these.’ She nodded towards the stone children.

Penance. That was a hot word. When anyone wanted to do penance, there was always a chance someone else wanted revenge. I wondered about the story behind the statues. ‘So, any more ideas why you were so worried when you arrived at the house this morning?’

She hesitated. ‘I don’t know. Because no one answered the phone earlier I suppose. I’m always worried about Abbie’s health. I’m sure he probably does know what he’s doing, but I always wonder if Phil gets her medication right when I’m not around.’

‘What medical problem does Abbie have?’

Rachel rubbed her nose. There was something sticky in the air between us. Something she wasn’t saying. She didn’t seem numb and shocked any more – there was a new sharpness about her. She huddled into her coat as if suddenly aware of the cold. ‘You never think about your heart, do you, until it goes wrong? And then you think about it all the time.’

‘Does Abbie have a heart problem?’

‘Yes. It’s in Phil’s family.’

‘So, did Abbie have a sister?’

‘Jess. She died four years ago. She was only six. Not of the heart problem though. An accident.’

‘I’m sorry. Were they twins?’

Rachel shook her head. ‘Abbie’s Phil’s daughter and Jess was mine. I adopted Abbie after Phil’s ex-wife died.’

I turned to Rachel and looked at her dead eyes; weighed up whether to say anything; decided I should. ‘I lost my older sister when I was ten. She was fifteen.’

Some of the tension left her body. Maybe I shouldn’t have mentioned my sister. It wasn’t exactly in the manual of recommended interviewing techniques. But Rachel Thornton was a person too, and I found if you shared with people, they often had a strong urge to share back. Sometimes they’d even share that they’d killed someone. Most murderers didn’t intend to kill – it was something that happened in a loose moment that slipped away from them, when they were so furious they weren’t really noticing what they were doing. Often it was a relief to explain and justify.

Besides, my story was public now. Google my name and there it was. Poor me. Found my sister hanging from a beam, and I was only ten. Everyone knew. After I’d kept it to myself all those years. I felt like someone who’d fallen asleep drunk and woken up with no clothes on.

We sat together on the freezing bench, touched by our own individual horrors.

I hoped she might say more but she didn’t, and I decided not to push it for now. We’d need to get her in for a formal statement anyway.

‘Is Abbie’s heart okay?’ I asked.

‘She had a transplant last year.’

‘That’s why you can’t let her have pets?’

‘That’s right. She has a suppressed immune system.’

I pictured the needle marks on Abbie’s arms. Remembered her hugging the dog, then wrapped in his blankets and Carrie’s scarf, after nearly freezing to death. Not ideal.

‘Is she okay though?’

‘Yes, of course.’

‘Was there a problem with the transplant? Is that what your husband’s artwork’s about?’

‘Of course not. This has nothing to do with Abbie’s heart.’

I turned to look at Rachel’s face.

‘Do you mean your husband’s death?’ I asked. ‘Why would it have anything to do with Abbie’s heart?’

She blinked a couple of times and shook her head. ‘It wouldn’t. I didn’t mean anything. Abbie’s heart’s fine.’

4.

‘I can’t take on a big case,’ I said. ‘I spoke to the victim’s wife at the scene, but I’ll have to hand it over to someone else. It’s really bad timing for me.’

DS Jai Sanghera leant against the window in my room and hitched one leg up onto the sill in a bizarre yoga-style move. ‘Have you told Richard why you’re off next week?’

I took a step towards the door and lowered my voice. ‘He wants to see me now. I can’t tell him. I said I was spending time with family and catching up on some DIY and stuff.’

‘If you don’t take it on, he’ll ship someone else in. DI Dickhead from Nottingham.’

My stomach tightened at the thought of Abbie being grilled in one of our dispiriting interview rooms. ‘Maybe he’ll bring that woman in? She’s alright.’

Jai shook his head. ‘She’s tied up on a big case already. Human trafficking. No chance.’

I’d told Abbie I’d make sure she was okay. But I couldn’t let my family down. I swallowed. ‘I can’t delay my time off. You don’t know what it’s like.’

‘I know what it’s like to lose a grandparent. Tell him you can’t take the case. We’ll cope with Dickhead.’

*

It was only Monday afternoon, but I felt as if I’d had a full week at work. And I still hadn’t called Mum back. I shoved open the door to DCI Richard Atkins’ lair.

‘Ah, Meg.’ Richard’s customary greeting, whether he was bollocking or praising. ‘Sit down.’ He indicated his spare chair, famous for its ability to engulf the unwary. I suspected it housed the putrefied remains of previous DIs.

I stayed standing. ‘I can’t take on this case. I’ve got time off next week.’

Richard looked at me over piles of papers and the tiny cacti he used as paperweights. He rearranged them each morning and I was always looking for meaning in the arrangements, as if he was sending messages about his mood or the state of the world. He cracked his fingers. ‘You let the victim’s daughter fall into freezing water,’ he said. ‘You mustn’t be so careless. She could have been seriously hurt, and the evidence on her nightdress is compromised. What on earth were you thinking?’

‘It was an accident. She wanted to get the dog a drink, and – ’

‘The dog? You mustn’t let your love of animals affect your actions.’

I opened my mouth, so stunned by the unfairness of this that I didn’t know what to say.

Richard had put on weight, and was getting the look of a bulbous-nosed drinker. Did he know he was becoming a walking cliché? Eating unhealthily and turning to the bottle because his God-bothering wife had left him and was no longer providing healthy, vegetable-laden meals?

‘I’m very disappointed,’ Richard said. ‘And what’s this about the victim’s wife reporting a stalker and us ignoring it?’

‘We didn’t exactly ignore it, but she didn’t give us much to go on. And her phone calls stopped about six weeks ago. She hasn’t been in touch recently.’

‘It’s the last thing we need. Stalking’s hot at the moment. Pray to God it wasn’t the stalker that did for him.’

This was modern policing. It wasn’t so much the brutal throat-slitting that was tragic as the fact that we might get blamed. ‘If we’re asking any favours from deities,’ I said, ‘maybe pray we catch whoever did it and that no one else gets hurt.’

‘Yes, yes, of course. But the press’ll act like we went in with a lynch mob of Derbyshire detectives and cut his damn throat ourselves.’ Richard rubbed the slack skin on his neck. ‘And you shouldn’t have gone in without back-up.’

‘I know, but – ’

‘You could have been killed.’

‘I had to check – ’

‘You need to stick to procedure, Meg. No more doing your own thing. Especially when we’re already on the back foot with this bloody stalker fiasco.’

‘But someone could have been bleeding to – ’

‘There’s no excuse for putting yourself at risk.’

Christ, was he ever going to let me finish a sentence? I’d noticed that more senior people just talked over him, so they both ended up banging on at the same time, gradually increasing the volume until one of them gave up. I didn’t have the energy.

‘And I know your last murder case ended in a relatively good outcome. But, as we’ve discussed, you can’t behave like that again. What if you’d been seriously injured? Or killed?’

‘I know. It would have looked bad, wouldn’t it? But I was suspended, so it wouldn’t have been your fault if I’d drowned in a cave or plunged to my death in an old windmill.’

‘I’m not sure that’s how the press would have seen it.’

‘Good to know it’s my welfare you’re concerned about.’

Had he even heard me say I couldn’t take on this case?

‘You have to stick to the rules,’ Richard said. ‘Follow the evidence. This new case is a good opportunity. Show you can be a team player and do things properly.’

Clearly not.

‘I’m off from next Wednesday,’ I said. ‘It’s best I don’t take on this one.’

‘You’re not going away, are you? So you can delay your holiday if necessary.’

‘I don’t think I can do that.’

Richard narrowed his eyes. He knew how important work was to me, almost to the point of it being pathological. Why in God’s name had I not planned a convincing lie about a trip to Africa to save sick lions, or treatment for an obscure and terrifying gynaecological condition? I could feel my pulse quickening at the possibility that he’d work it out.

‘I’m trying to be fair here, Meg, but I’m a little confused. We could get Dickinson over from Nottingham, but I’m not sure about your level of commitment to the job if – ’

‘I’ll do it,’ I blurted. ‘I’ll delay my time off if necessary.’

‘Good. And I’d like you to work with Craig.’

‘Craig?’ I said weakly. ‘But . . . ’ I stopped. There was nothing I could say.

‘I’m not telling you you’ve only got six months to live, Meg. I’m asking you to work with a perfectly competent sergeant.’

‘Actually, Richard – ’

‘Right. Let’s do the briefing.’

*

The incident room felt hot and muggy, like somewhere you could catch malaria, despite the fact it looked ready to snow outside. A trace of ill-person’s sweat hung in the air, and cops coughed aggressively over one other. But the excitement of dealing with a murder fizzed through the air alongside the winter bugs. I shoved aside my worries about time off and family, and allowed myself to be swept along.

‘Are they Jackson Pollocks?’ Jai nodded towards a collection of blood-spatter photographs.

I frowned, pretending to disapprove of him.

Richard strode in, took off his jacket, and chucked it at a chair. It missed and fell on the floor. I nearly reached down for it, but realised there were precisely three men nearer to it than me. Why should I dash to pick the damn thing up? Especially given the way he’d just spoken to me. I noticed DC Fiona Redfern twitching too. But neither of us moved.

Jai retrieved the jacket.

‘Thank you, Jai.’ Richard shifted aside to let me into the hot spot. ‘It’s a long way down for me these days.’

I took a deep breath of the dubious air and stepped forward. ‘Right. The victim is Philip Thornton. Forty-eight-year-old male. Stabbed in the early hours. He was in the house with his ten-year-old daughter. Wife was apparently at her mother’s.’

Jai yawned inappropriately.

‘Am I boring you?’ I said.

Craig leered. ‘He’s been up late with his new girlfriend.’

I didn’t know Jai had a girlfriend. I looked at his open face. Would he not have told me? They were all staring at me. I realised I should say something corpse-related. I spoke too loudly. ‘The victim’s carotid artery was cut with a very sharp knife. As far as we can tell, he was asleep and didn’t put up any fight.’

‘So, whoever did it went in with the intention of killing him?’ Jai said.

‘Looks like it. There was evidence of an intruder in the house.’ I pictured the upturned drawers in the study and bedroom – remembered my feeling that something wasn’t quite right. ‘Possibly.’

‘We got into his phone. Very interesting.’ Our allocated digital media person, Emily, was the antithesis of every stereotype about sad geeks. As well as obviously being female, she glistened with Hollywood shine – all advert-white teeth and smooth-skinned perfection. Every time I saw her, I did a double-take, especially when she was surrounded by her dowdy colleagues, like a dahlia amongst dandelions.

‘Go on, Emily,’ I said.

‘There were missed phone calls and texts between 4.15 a.m. and 4.30 a.m. from a contact called Work. A mobile phone which we’re tracing.’

Emily clicked something and a list appeared on a screen behind us.

Call History:

4.15 a.m. – Work.

4.16 a.m. – Work

4.18 a.m. – Work

4.20 a.m. – Text from ‘Work’: ‘Phil, I need to talk.’

4.22 a.m. – Text from ‘Work’: ‘Why are you ignoring me? I know Rachel is away. I have to talk to you.’

4.30 a.m. – Work

4.33 a.m. – Work

4.40 a.m. – Work

‘Did he reply to any of this?’ I asked.

‘Nope. Not at all,’ Emily said. ‘I’ll leave you to it. I’m off to find out who Work really is.’ She walked off, leaving the room feeling drab in her absence.

I turned away from the screen. ‘The victim’s wife thought he’d been secretive recently. Which obviously ties in with the calls and texts. And the woman who reported the child in the woods said she saw a car driving up the lane to the house. In the night. The lane doesn’t go anywhere else. It’s possible this Work person could have gone to try and meet Phil.’

‘It fits the provisional time of death,’ Jai said.

The energy in the room bubbled up at the prospect of a good early lead. ‘The wife’s also been in touch previously about a stalker,’ I said. ‘And unfortunately – ’

‘We in our wisdom ignored her.’

Richard was starting to piss me off. He was obviously riled about me having the audacity to want time off.

I folded my arms and pivoted away from Richard. ‘We need to look at the details, obviously. But we didn’t have a lot to go on.’

‘We’ll get the blame for this,’ Craig said. ‘We need to cover our arses.’

‘Mainly we need to find whoever killed him,’ I said.

Richard coughed. ‘Quite so, Meg. And also cover our arses.’

I glanced at the texts shining guiltily from the screen. ‘If it was someone he was having an affair with, they could have faked the intruder. There was something not quite right about that. And we should look at the woman who found the girl in the woods. It’s a bit convenient that she saw the car in the middle of the night. And she seemed to know who the girl was. Plus, I had a feeling she might have known the victim too.’

They all nodded sagely except Richard, who scowled at me. ‘A feeling,’ he said. ‘You need more than that.’

I ignored him and carried on. ‘And, oh I don’t know, it’s probably not relevant, but . . . ’ As soon as that came out of my mouth, I knew it wasn’t confident enough. Not Alpha enough.

Richard jumped on me. ‘Why are you telling us then?’

I felt sweat prickling under my armpits. Maybe it wasn’t just about Richard’s wife leaving. Maybe he was going through the male menopause. I’d read somewhere that men’s moods were more cyclic than women’s, contrary to received (male) wisdom.

I raised my voice. ‘Okay, I think it might be relevant. There was something strange going on in that family.’

‘Other than the bloke having his carotid slashed?’ Richard said. ‘What do you mean by that?’

‘His artwork. Her reaction to it.’

Jai gave me a puzzled look. Craig rolled his eyes and said, ‘We’ve got an absolute corker of a lead with those phone calls and texts and – ’

‘I saw the photos of that artwork,’ Fiona said. ‘It’s creepy. Hearts doing weird things. Do you think he was on drugs when he did it? It’s not normal.’

Craig wouldn’t like being interrupted by Fiona. He was tapping his fingers on his knee – that meant he was about to get snide or aggressive. He’d have a dig now.

‘Poor bastard’s had his throat slit,’ he said. ‘And you ladies are all over the fact he did a bit of screwed-up art in his spare time.’ There it was.

I pretended Craig didn’t exist. I even managed to do something weird with the focus of my eyes, so I was staring directly through him at the coughing IT guy behind. ‘The victim’s daughter had a heart transplant last summer. There was a card I think might have been from the family of the donor. But the art suggests all’s not well. And the way the wife talked – it made me think there was something wrong.’

‘When you hear hoofbeats,’ Richard said. ‘Think horses, not zebras.’

‘Huh?’ Jai said.

‘Look at the most likely explanations,’ Richard said. ‘It’s not hard to understand.’

‘It could have been the wife. If she found out her husband was having an affair.’ Fiona was clearly not interested in the zebras, and was of the opinion that an affair was good grounds for throat-slitting.

‘And she was desperate to get back inside the house,’ I said. ‘I think she may have messed up the scene deliberately. And someone had been in the shower.’

‘But her story adds up,’ Craig said. ‘She was at a petrol station in Matlock at nine in the morning.’

‘She could have come to the house earlier and then gone back to Matlock. We need to check. There are no immediate neighbours, and there are ways to the house that avoid CCTV altogether, but we can look at the camera on the main road.’ I raised an eyebrow at Richard. ‘And the spouse is always a horse, don’t you agree?’

‘Didn’t the little girl see anything?’ Fiona asked.

‘She was on sleeping pills for night terrors she’s been having. We haven’t been able to get much sense out of her. It looks like she must have woken up, wandered through to her parents’ room, found her father, tried to wake him and got blood all over her, and then run out into the woods.’

‘How horrendous,’ Fiona said.

‘She’s a lovely kid too.’ I felt that weight again. The responsibility to solve this, for Abbie. ‘You know this area well, don’t you, Fiona?’

Craig butted in. ‘Her gran does. She’s on our Blue Rinse Task Force.’

I smiled at Fiona. ‘Do you know about a folk story associated with that house? There are some statues of children in the woods.’

‘Really, Meg.’ Richard wafted his arm as if he was standing over a decomposing rat. ‘What does this have to do with the investigation?’

‘His wife said the victim was obsessed with the statues, and something about wanting to do penance. It might be relevant. He’d replicated one of them out of wood, except with its heart ripped out.’

The door bashed open and Emily walked in and stood as if under stage lighting. ‘Got the trace on that mobile phone,’ she said. ‘It’s a colleague of Phil Thornton’s. Karen Jenkins.’

5.

Karen Jenkins shuffled into the interview room, bashed her leg on the drab grey desk, and apologised to it. I smiled. It was the sort of depressingly British thing I’d do.

Craig sorted out the recording apparatus and took her through the formal bits and pieces. Jai was watching from an observation room. It was still only the afternoon of the first day and we had a solid lead. I prayed we could get this one cleared up fast so I could avoid my lie to Richard being exposed. There was no way I could delay my time off, whatever I’d said to him.

Karen was in her mid to late forties, and reminded me of one of those hairy dogs whose eyes you never see. She cleared her throat a couple of times and licked her lips. Glanced at me and quickly looked away. ‘Sorry. I’m not used to being questioned by the police.’ She gave a high-pitched laugh. ‘Can I make notes in my pad? It calms me.’

‘Yes, of course.’ I leaned back in my deeply uncomfortable chair.

She shook her head so her hair covered her eyes almost completely. ‘Right. Yes. No. I can’t believe it. Can’t believe it happened.’ She picked up her pen and tapped it against her pad, but didn’t write anything.

I chatted nonsense for a while to relax her and calibrate – noticing what she did with her hands and face when she was talking about the weather and the traffic.

Once I’d got the feel of her, I asked casually, ‘Were you close to Phil Thornton?’

She swallowed and looked down, much stiller than before. ‘We were colleagues. Not close as such.’

‘His wife was concerned someone might have been following him. Do you know anything about that?’

She hesitated. I could see her breathing. Raised voices drifted in from in a nearby room. ‘No. Sorry,’ she said.

‘Anything worrying him that you were aware of?’

‘Nothing that would get him killed,’ she said, more abruptly. ‘He was worried about Abbie. And about his wife, I think. She’s a bit odd.’ She made a few swoopy doodles on her pad.

There was a smell in the air, familiar but wrong in this context. I looked up sharply and scrutinised her. Had she been drinking?

‘When was the last time you went to Phil’s house?’

Her eyes widened a fraction. ‘I don’t know. Ages ago.’

‘What was the occasion?’

‘You should be looking at his wife, not me,’ Karen said. ‘He was worried about his wife.’

‘The occasion you went to his house?’

‘They had me and my husband round. I can check the dates and get back to you.’

I glanced at the wedding ring on her hand. ‘Look, you need to be totally honest with me. Nobody’s judging you. But what kind of relationship did you have with Phil?’

‘We were close. Nothing ever happened.’ Jagged lines on the pad, deeper now, solid fingers gripping the pen, her body tense and so different to when she’d been chatting earlier.

‘Karen, I don’t care if you were having an affair, but you need to tell me the truth.’

Her voice shook, as if she was about to cry. ‘We were friends.’

I waited a moment, but she said no more.

‘Have you ever watched those TV murder mysteries where the victim’s friend is always forging Dutch masters or stealing prize orchids or something like that?’ I asked. ‘So they lie to the police, and you’re screaming at the telly saying, “Just tell them about the sodding orchids” because it never turns out well. Have you watched any of those?’

She nodded and licked her lips again, looking on the verge of tears, the skin beneath her eyes beginning to puff up.

‘Where were you on Sunday night?’ I asked.

‘Me? I was at home. You don’t think I did it? I would never . . . ’ She was crying now, gulping and wiping her hand over her nose.

Craig dived in. ‘You see, we have these texts and phone calls on Phil’s phone.’

Karen jumped and looked at him, as if she’d forgotten he was there. ‘I don’t know what you’re talking about. You think I . . . Oh my God.’

‘You went there, didn’t you,’ Craig said. ‘To his house.’

Karen flipped her gaze from me to Craig, and to me again, and shoved herself back in her chair as if wanting to put distance between us. She moved her foot in anxious circles over the dismal grey carpet.