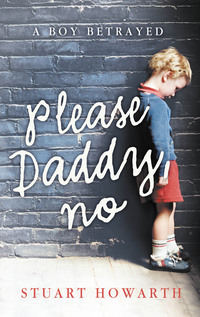

Please, Daddy, No

There were some new houses being built down the bottom of Smallshaw Lane, which meant there were wagons full of earth streaming up and down all day long. A bunch of us used to stand at the top of the road and shout out to the men driving the trucks to give us rides. For a while they obliged and then the foreman told them to stop. The other kids persuaded me to hide in the bushes and jump out in front of one of the huge vehicles at the last moment, forcing the driver to stop with an explosive hiss of air brakes.

‘What you fuckin’ playing at?’ he wanted to know.

‘I don’t know where my mummy is,’ I replied, as I had been instructed, and started crying.

‘Come on up here then,’ he said, his heart softening.

As soon as he opened the cab door the others would all troop out of the bushes.

‘Fuckin’ ell, your mammy’s been busy.’

The ruse worked every time, and usually resulted in us getting to share their lunch and drinks. Once they dropped us off on the site we would play happily amongst the diggers and tractors.

Quite often it was just me and Christina in the house because Shirley would be in hospital having operations on her legs, head and back, or my Nan would be looking after her. She and my Granddad Albert lived about five miles away and we often used to go over as a family for Sunday lunch. Granddad was a short, sturdy sort of chap who used to shout at me a lot. They lived in a private house and had lots of ornaments everywhere, like an Aladdin’s cave, which I just ached to pick up and look at but wasn’t allowed to. They had a little dog, Sparky, who felt so soft and smelled so clean compared to our filthy, smelly dogs. On the way home after Sunday lunches Christina, Shirley and I would lie on the floor of the van, half asleep, and I would watch the orange streets lights flashing past the windows and imagine we were on a magic carpet ride.

Sundays were good because we could go to Sunday school, which the Salvation Army organized in a hut a few doors down from our house. We would sing songs and be told stories and even did some colouring-in of pictures of Jesus. They would give us presents like little gollywogs holding banjos and other musical instruments. They were the sort of thing you could have got for free off jam jars, but we loved them because they were pretty much the only presents we were ever given.

Chapter Three THE PEN

Dad had an allotment. Not one of those little strips of vegetables with a makeshift shed at the end, but about an acre of land, like a smallholding, filled with ramshackle outbuildings. It was known as ‘the pen’. Sometimes there would be twenty or thirty kids following him across the wooded piece of land behind the house and up the hill to the pen, with Shirley in her wheelchair, making him look like some sort of grubby Pied Piper.

The ground amongst the trees along the route was always strewn with litter and the pen itself was surrounded by a makeshift wall of house doors, so that no one could break in and passers-by couldn’t see what was going on. It was Dad’s little private kingdom. Behind the wall and padlocked gates was another world where he raised chickens, geese, ducks and pigs and stored yet more scrap salvaged from his rounds. There was a big black boar called Bobby, and a sow, terrifying, stinking great creatures that wallowed and snuffled in their own filth. An abandoned car stood, stripped and rusting, just inside the gates, waiting for someone to turn it into scrap.

In one of the sheds lived my dad’s dad, whom we knew as ‘Granddad from the Pen’, a dirty, toothless old man who would always smell of whisky and grab me between my legs, or pinch my bum and rub his bristly chin against my face, which he thought was funny but which hurt. His clothes, which he wore day and night, were rags, like a tramp would wear. He also thought it was funny to throw his false teeth at me, even though I hated it. Dad used to do the same thing sometimes with his. Even at that age I could sense there was something about Granddad from the Pen that wasn’t trustworthy.

I think his wife must have chucked him out years before and he went to live with Auntie June, Dad’s sister, but she got fed up with him too and now he just had a camp bed in the corner of one of the sheds. He kept a pile of dirty books underneath the bed, which he was happy to get out for us, making us giggle with embarrassment and exclaim in horror. I’m sure the magazines must have been rescued from the dustbins, just like everything else in our lives. Granddad from the Pen spent a lot of his time down the pub. Only later did I discover he was an alcoholic; then I just knew he always smelt of booze, like Dad, only worse.

There had been some sort of falling out between Mum and Granddad from the Pen, although I never knew the details, but he stayed away from the house for a while. The day he did come back he came with a present for me, a pink bike. I didn’t care what colour it was, it was a bike, something that none of the other kids in Smallshaw had, unless they were old ones with solid tyres that you couldn’t use to jump on and off kerbs without jarring every bone in your body. Granddad from the Pen was obviously drunk, having just come out of the pub, and went in to see Mum, leaving me outside with my new possession.

I set off proudly to pedal round the neighbourhood. It was a glorious summer’s day and I felt like the king of the area, until I was stopped by a policeman, who enquired where I’d got my bike from.

‘It’s a present from my Granddad,’ I said, wondering why the policeman was being so nasty. ‘I think we should go and talk to your Granddad,’ he said. It turned out Granddad had nicked the bike off some little girl when she got off to go into her house just as he was passing. It broke my heart to see the policeman taking it away.

Going up to the pen was like visiting a little zoo, and all the local kids loved it. We would play hide and seek and other games. They would always be coming round pestering to find out if we were going up there. I used to love to root through the drawers around the sheds because they were always crammed with so much rubbish, just like our house. It seemed like a treasure trove to a four-year-old, another Aladdin’s cave, although a bit different to my Nana and Granddad Albert’s.

The pen was one of four, like some peasant farms left over from the Middle Ages, partially illuminated at night by the street lamps on the lane outside. It wasn’t far to walk, but it was hard for me to keep up with Dad’s long legs when it was just him and me going up there. If it was just us he would grow impatient with waiting for me to catch up and would stride off ahead, forcing my little legs to go faster, almost as if he didn’t want anything to do with me, as if he was trying to get away. If Mum was with us he would put me on his shoulders, but if it was just us he would become angry as I lagged behind and would grab my hand and drag me off my feet, nearly jerking my arm out of its socket. Dad would go up to the pen every day because the animals needed feeding. He would collect any bit of food he could get his hands on and boil it up in big pans at home, adding the scent of pigswill to the existing smells of pee, dogs and fags.

The pen was a great place for a small boy to go, but sometimes I would make Dad cross and there would be flashes of nastiness as he gave me a push or a pinch to let me know I had disappointed him yet again. I knew that I must always be good and never anger him. He was only in his early twenties at that time, but he had a presence even then that made me wary. I had a feeling that he didn’t like me and I was willing to do anything in order to change that. He used to insist that I collected the eggs from under the hens, which used to terrify me. They made so much fuss, flapping their wings and pecking at me with vicious beaks. I never wanted to do it, but I knew I had to do what he told me because he was my dad and he wasn’t someone you would disobey. He used to keep ferrets as well, to help keep down the rat population, and he liked to put them down his trousers, and down mine. It was a horrible experience, feeling their claws digging in, believing they were biting, but he thought it was funny and that I should learn how to be brave about it. He was always trying to ‘make a man’ or ‘make a farmer’ of me.

I didn’t like the way he would read magazines full of women while he was having a wee; at least I thought that was what he was doing. It was a bit confusing and very frightening.

Violence and bullying were the norm around Smallshaw. There was one family in particular who used to bully everyone. We used to go round to their house quite a bit, even though we thought they were disgusting, often ending up sleeping on their couches or several of us to a bed. Their mother was a big brute of a woman with no teeth, who used to sit there with her legs apart and no knickers on. Even as kids, Christina and I knew she was repellent. She would get her boys to give her love bites on her neck so people would think she had a man. She organized all the robbing in the area, like a sort of modern Fagin, sending the kids off to pinch clothes off washing lines, taking the spoils back to her house to be shared out. She was always picking fights and her kids followed her example.

One day Christina got into a fight with one of her daughters in the street and came in crying. I think she’d had clumps of her bright red hair pulled out in the heat of the battle. That family was always fighting and bullying one another and anyone else they could pick on, but this time Mum decided it had gone too far and went round to tell their mum what she thought of her. Christina and I watched from the window as the two women set to fighting in the street outside, punching and scratching and kicking, until eventually Mum came back in with blood all over her face. I was frightened but proud at the same time that our Mum wasn’t scared to stand up to such a woman. She had stood up for Christina, just like I liked to believe Dad would have stood up for me in the same circumstances.

‘It’s all right, Mum,’ I kept saying, trying to calm her crying when she came back in, cuddling her and wiping away the blood.

That fight was the final straw that convinced Mum and Dad that we should move from the street. Just at that time Dad’s sister, June, announced she was moving out of her house in Cranbrook Street, a much better area, and asked Dad if he would like to buy it off her. Moving to the ‘private sector’ was like moving to another world for us. I guess Dad must have been able to get a mortgage at a good rate, working for the council, because they started to lay plans.

Despite this good news, there had been another incident that had left me troubled. We were on a family holiday to North Wales. We had driven down there in Dad’s old Transit van, which was always getting punctures and having to pull over for repairs, but we would all be piled happily into it, with me, Christina and Shirley sitting or lying on mattresses in the back. Travelling loose like that was hard for Shirley because she was always in so much pain and there was nothing to stop her from bouncing and rolling about on every bump and corner. Christina and I would try to comfort her, reassuring her it would be all right, but the pain was terrible for her.

Dad’s other sister, Doris, lived in a place called Penmaemawr, not far from Llandudno, and we stayed in a caravan at the Robin Hood camp in Prestatyn. I had never stayed in a caravan before and it all seemed like a great adventure. Being able to go to the seaside was so exciting and it reinforced the feeling we had that we were special and better than the other families around us in Smallshaw Lane. No one around our way ever went on holiday and I felt proud to have a dad who could organize such a treat.

Still being so small, just four years old, the beach appeared enormous. We spent the first afternoon building sandcastles and the girls were as happy as I was to be playing somewhere where there was no one picking on us or trying to spoil our fun. We felt completely carefree. At some point I decided to go down to the water by myself. The tide was out and I had to splash for what seemed like miles across the wet sand to get to the sea. The sky was bright blue above my head and the ocean stretched away forever into the distance, its edges lapping and rolling across my bare feet as I danced with delight in the foam, the rest of the world forgotten, including my family sitting behind me on the beach.

Back on the dry sand Mum must have noticed that I had strayed too far for safety, and Dad must have told her not to worry, that he would go and get me. I didn’t hear him coming, didn’t hear him calling me to come back, then suddenly I was aware of his presence and he was on me, grabbing me hard, hurting me.

‘You naughty little bastard,’ he yelled as he squeezed me with all his might. ‘I’ve been shouting for ages.’

‘I’m sorry, Dad, I didn’t hear you. I was splashing.’

‘You are a fucking liar. You’re just plain fucking naughty, aren’t you?’

He punched me to the ground, forcing my face down in the sand so that it filled my mouth and nose and eyes.

‘Do you want me to tell your mum that you have spoilt the fucking holiday and you’ve ruined it for your sisters? Do you? Do you?’ Every question was punctuated by another punch.

‘No, Daddy, please.’ I tried to speak through mouthfuls of sand. ‘I’m sorry.’

I was struggling in his powerful grip, unable to breathe, panicked. After what seemed like forever he yanked me up.

‘Get up, you little cunt, and stop fucking crying. If you don’t stop crying I’ll tell Mum you’ve been bad and naughty.’

As he let go of me I pulled myself up on wobbly legs, still able to feel his grip on my neck. Dad was cross with me and I just wanted to please him, and I didn’t want him to tell Mum how naughty I was.

‘Now get back there and put a smile on yer fucking face.’

My legs were shaking as I tried to run to obey him, shocked and unable to understand what I’d done wrong. I just knew that I must try much harder to be good, so he wouldn’t be angry with me, so he would love me. I tried to hold his hand as we made our way back to Mum and the girls but he pulled it away and walked too quickly for me to keep up as I stumbled along.

‘Have you been having a good time?’ Mum asked when we reached her, and I just smiled and nodded, not able to trust my voice to be steady.

Starting school, just a little way from our house, was an eye-opener, like my visit to hospital. The teachers were so kind and caring, so different from the adults in my home world. The kids in the class were different from the ones who played in our street and came round our house. They didn’t want to pull my ears or my hair or hit me or be nasty to me. When I realized what a friendly world it was it was like a huge weight lifting off my shoulders. There were crayons and pens and paints, drums and even a violin, which I’d never seen before, and I was allowed to touch them and use them and everyone encouraged me and praised whatever I did. No one seemed to think I was naughty. There were some familiar faces from our estate, which was comforting once I realized they were going to behave differently at school from the way they behaved in the streets and houses. It was such a relief to be somewhere that didn’t seem at all threatening or frightening.

Shirley had to go to a special school because of all her physical problems, so she would be picked up in a taxi or ambulance each morning, and Christina and I would make our own way to and from our school. One afternoon we came home to be told that we were going to be moving to Auntie June’s house in Cranbrook Street. From now on, Mum explained, it would be our house. Overcome with excitement, I begged for us to go round and look at it, and Dad agreed to take me and Christina round there.

It wasn’t far, so we walked there together, him striding ahead in his Wellingtons, us galloping along, trying to keep up as he cut down all the back ginnels and alleys. We’d been there before, to visit our cousins, who seemed spoiled to us, always having everything that we didn’t – carpets, wall lights, proper cupboards in the front room, a gas fire in a stone-built fireplace and fancy patterned wallpaper. The carpet was purple and seemed to blend with the walls. I would get into trouble for keeping on turning the lights on and off because I’d never seen anything like it before. They even had a proper television, which worked all the time and didn’t have to be hit. It seemed such a big, grand place, three storeys tall, and with its own cellar. We always wanted to stay there. Then it had been their house, but now it was ours and we could hardly contain ourselves.

As we approached the house that our dad was going to get for us, I looked up in awe. It stood at the centre of the terrace, its front door opening directly on to the street; the slot for the post low in the bottom of the glass front door – I hadn’t noticed that before. I never knew you could have a letterbox there. It seemed like another sign that we were moving up in the world. The roof rose up to pointed eves, like the sort of houses families lived in on television. As Dad let us in it felt like we were walking into a big private castle.

The other kids in Smallshaw didn’t let us get away without some teasing: ‘Think you’re better than us, do you, just because you’re moving to a private house?’

‘No, we don’t,’ we protested, but we did.

Christina and I ran from room to room, exploring every nook and cranny as we went. The attic rooms at the top of the house were going to be ours, which we thought were the best rooms in the house. It all seemed so huge, and in our rooms there were even wardrobes built into the eves that we could actually walk in and out of. I stood at the window, staring down, thinking it was thousands of miles to the pavements below, feeling a delicious little frisson of fear when I got too close to the sill. I felt like the king of the castle. Dad told us the council might give us a grant so we could build a special bedroom for Shirley, maybe even installing a lift so Mum didn’t have to carry her up and down stairs all the time.

I did feel a little sad to be leaving some of the kids in Smallshaw who had been my friends, but I was too excited about moving away from the bullies to somewhere so new and different to grieve for long.

Chapter Four A MORE PRIVATE WORLD

The house in Cranbrook Street that had seemed like paradise on that first visit became as much of a junk heap as our house in Smallshaw within a few weeks of us moving in, filled with Dad’s scroungings. He found a huge reproduction of Constable’s famous Hay Wain picture on the bins and hung it in pride of place in the front room. I’ve never been able to see that picture since without thinking of him.

The house needed rewiring, but he didn’t bother, so the electric heaters never worked. The power kept failing upstairs and we would have to run cables up the staircase in order to use any appliances or lights.

We moved to a new school and whereas we had fitted in with other kids from the streets of Smallshaw, most of whom were pretty much as dirty and scruffy as us, now I really stuck out. We tried to make some new friends, but I think we were seen as little more than street urchins by the neighbours. I got a bit of bullying and teasing at school for my appearance and because we obviously lived in poverty. Because I was getting used to Dad hitting me, every time I saw someone raise their hand I would immediately fall to the floor and roll into a ball, covering my head to protect myself from the blows I knew were coming. It wasn’t long before the other kids realized how easy it was to get me to do this.

There wasn’t the same culture of neighbouring as there had been in Smallshaw; people didn’t just pop in and out of one another’s houses and sit around for hours. We were left pretty much to ourselves and Dad started to become more and more of a tyrant in his own little kingdom. He started shouting at Mum a lot, especially after he had been to the pub. She could never do anything right. Cranbrook Street was perfect for him, with the pub on one corner and the chip shop on the other, and he soon developed a regular routine. He would be up on his bin round early and then into the pub between twelve and three, before coming home for a sleep.

He always smelled of the bins and once he’d pulled off his sweaty wellies he would sit with his feet in a bowl or pan of hot water, ordering me to wash them and scratch them for him. It was a disgusting job because they stank so badly. I would peel his socks off for him and they would be stuck to his feet, rock hard with sweat after spending so long in his boots.

As he got used to having control, he started to become stricter about the way our lives were run. Finding he had so much power went to his head. We started to be given definite bedtimes, when before we had pretty much run wild. He didn’t like it if he had to carry Shirley around and if she wet herself he would shout at Mum to ‘get her fucking changed’. The atmosphere was getting much worse, but he was still my dad and I still loved him. I had no one else to compare him with anyway.

After his afternoon nap he would wake up again about seven in the evening and go back down the pub. We would all try to get to bed before he reeled back in and the rows really started. We could hear the shouting and screaming downstairs and even then I knew Mum was getting beaten. He told her she had to get a full-time job to help with the money, and she did as she was told. Until then she had at least been there sometimes, or at least not far away, and suddenly she was gone for long periods of the day, and I felt lonely.

The glimpses of nastiness and aggression that I had seen up at the pen, which had exploded on the beach in Wales, now became regular occurrences, and they escalated almost daily.

‘Don’t touch those fucking crusts,’ he would yell if I went to eat some bread. ‘They’re mine.’ Whenever any of us had bread we had to cut off the crusts and give them to him if we didn’t want a beating.

If I touched something that was his, or was naughty in any way, I would get battered. The trouble was I didn’t always know when something I was doing would turn out to be on the forbidden list, although in the end it covered just about everything I did.

‘Don’t pick your nose!’

‘Stop picking your nails!’

‘Stop itching your bum!’

‘Stop scratching your head! Have you got nits?’

‘Dirty legs!’

‘Dirty knees!’

‘You’re a filthy little bastard. Go and wash!’

‘Look at the mess you’ve left round this basin and taps!’

‘Clean the fucking soap.’

‘Your bedroom’s a mess.’

‘You’ve left dirt on the sofa.’

‘Your coat’s dirty.’

‘Your trainers are dirty.’

He had started grabbing me regularly, screwing my face up in his powerful fingers and slapping me round the head. He would suddenly appear behind me when I was least expecting it and slap me or throw me against the wall, knocking the breath out of my body. I wished I wasn’t so naughty because it seemed my behaviour was making him really hate me, but I just didn’t seem to be able to work out what I was about to do wrong next.

I was constantly scratching and itching because I always had nits and worms; it was impossible to stop myself, and it seemed to drive him mad. Sometimes I’d itch my bottom and pull out a whole handful of worms.

To deal with the nits, he decided I had to have my head shaved regularly, for hygiene, which revealed the little points I had on my ears, giving him the opportunity to tease me, calling me ‘Spocky’ after Mr Spock in Star Trek, or Kojak. The other kids at school were taking the piss too, warming their hands on the top of my head in the cold weather. I hated it all.

The more he went on at me, the more I just kept thinking, ‘Please, Daddy, no,’ but he never stopped, never let up on me. He was changing, becoming angrier every day, and more and more disgusted by me. I knew I must be bad and naughty, because he kept telling me I was. I knew I was ugly, because he kept telling me, so I could understand why it must be so hard for my parents to love me, but I didn’t know what to do to make myself better and more lovable.