British Seals

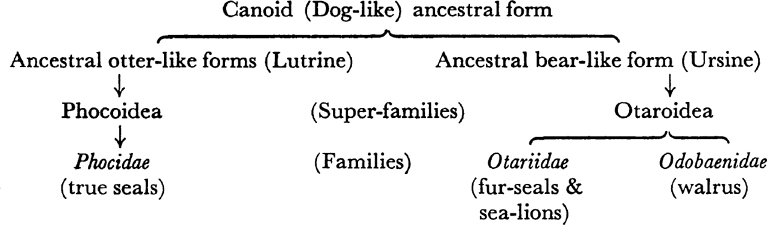

In discussing the characteristics of the Pinnipedia and comparing them with those of other marine mammalia it has been necessary to draw a distinction between the true, haired or earless seals on the one hand and the fur-seals and sea-lions or eared seals on the other. This is a very profound demarcation if we add the walrus to the second group. So clearly marked are these two groups that it is now thought that they had separate origins among the land carnivora, the true seals being derived from otter-like ancestors and the fur-seals and their relatives from bear-like forms. This can be expressed as shown at the top of See here.

The Otariidae are the least modified for marine existence. They retain a prominent external ear flap, there is an obvious neck region between the head and trunk, so that the body form is not perfectly streamlined or bobbin shaped, and their hind-limbs can be turned forward and used on land as feet. The pelvic region is also very obvious when they are on land. On the other hand the claws are much reduced either in numbers or size, and the flippers of both hind- and fore-limbs large and very well developed.

Their distribution is remarkable in that they are completely missing from the north Atlantic while present in all other oceans. Moreover, of the 12 species, 9 occur in the southern waters of the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific Oceans (including the circumpolar antarctic seas), 1 in sub-tropical Pacific waters and 2 in northern waters of the Pacific. Although this suggests that the family is southern in origin, palaeozoogeographical evidence (McLaren 1960) points to a north Pacific origin and that they evolved from a littoral canoid of bear-like appearance along the north-western coasts of North America, some time before the upper middle Miocene when their first fossils appear. Weight is given to this by the presence of the other ursine derivative, the walrus, in the circumpolar seas of the arctic. There are two sub-families: the Otariinae or sea-lions (with 5 species) and the Arctocephalinae or fur-seals (with 7 species). (See Appendix A, See here.)

The Odobaenidae contain two species,* one Pacific and one Atlantic, both in arctic waters. It is probably better to consider them as sub-species of the one species: Odobenus rosmarus. Like the Otariidae they still retain hind flippers which can be used as feet, but they have become greatly modified in other respects. They are specialised feeders on shell fish; the tusks are used for digging the bivalves out of sand or mud and then the flattened molars crush them†. In the males the tusks are particularly well developed and used for fighting as well. Unlike the members of both the other families the walrus is almost hairless although the vibrissae on the muzzle are well developed as tactile organs. Although they have been hunted for many years and almost exterminated, they are now protected and some study is being made of their habits. The Atlantic form breeds on some of the Canadian islands and occasionally an immature individual is reported on the British coast.

The Phocidae have an inconspicuous external ear, concealed by dry hair but usually visible when wet. The neck is short and thick, smoothing the body outline into that of the head. The fore limbs are small and used for grooming, with well developed claws. Their use in swimming is small, usually only for changing direction or ‘treading water’. On land they are not much employed in locomotion, although in the sub-family Phocinae the digital flexure enables them to clamber over rocks and broken ice. The hind flippers are the principal locomotor organs in water but trail on land. The movement of seals on land appears clumsy, but they can move faster for short distances than would be supposed. They occur in all the oceans of the world including the Mediterranean and Baltic Seas and several inland lakes which have had connection with the sea in glacial or post-glacial times. Until recently three sub-families have been recognised: Phocinae (with 8 species), Monachinae (with 7 species) and the Cystophorinae (with 3 species). Miss King (1966) however, has shown that the characters uniting the species of Cystophorinae are only superficial and differ in fundamentals, while many other characters show that the hooded seal is really a member of the Phocinae while the two elephant seals are closer to the Monachinae. Each of the two Sub-families are divided into two Tribes thus:

All the Phocinae are northern in both Atlantic and Pacific waters and their presently or recently connected seas and lakes. The Monachini or monk seals are tropical or sub-tropical while the Lobodontini are antarctic or sub-antarctic and circumpolar. The recent reallotting of the Cystophorinae species solves their equivocal position for the hooded seal as northern Atlantic and Pacific like the other Phocinae, while the elephant seals are brought more into line geographically with the southern distribution of the Lobodontini.

Despite the present wide distribution of the Phocidae the fossil evidence suggests their origin is Palaearctic from lutrine (otter-like) ancestors somewhere between early Oligocene and lower middle Miocene times.

Thus we can now say that the two seals which breed in British waters belong to the Phocinae, the two species, Phoca vitulina and Halichoerus grypus falling into the tribe Phocini.

Until recently much more had been discovered by British workers about the antarctic species of Lobodontini (and about the southern elephant seal) than about our own British species. How little was known until recently will become apparent when we consider each species separately, but something must be said about the reason for this neglect of our pinnipedes. Basically our ignorance has been due to the physical difficulties of obtaining information. Here we are dealing with animals which are amphibious. While they are on land we can watch them from the land but the slightest shift of the wind to send our scent towards them and they are away to sea where we cannot follow them. Extending this example to the period when they leave their breeding grounds on land, the problem becomes even greater. Antarctic forms, both mammals and birds, do not have a built-in fear of man and even the experiences of man’s culling them over the last century and a half have not induced such a timidity as we find in the northern Atlantic species. Consequently there has been no easy way in which naturalists and zoologists could become interested in seals or, even if interested, pursue the study of them without a great deal of trouble, preparation and expense. It has, of course, been easier to kill them than to study them alive, but even then the difficulties involved have been sufficient to enable both species to survive under as great a pressure of persecution as man has found it possible and economical to mount. Had they been solely terrestrial they would have disappeared long ago. Had they been marine and social they may well have been as reduced in numbers as their fellow mammals the Cetacea. Only in modern times with greatly increased resources of powered boats, helicopters and of camping facilities in remote and uninhabited islands and coasts has it been possible to pursue a planned scheme of research on the grey seal. Investigation on the same scale for the common seal is yet to come, in fact it may not be necessary as its habits do not appear to be quite so complex, but it may be almost equally difficult to prove it.

Undoubtedly the species of pinnipede about which most is known is the northern fur-seal (Callorhinus ursinus). Its value as a fur-bearing animal made it essential that the main breeding colonies should be saved and during this century the United States Fish and Wildlife Service has carried out a series of investigations of the greatest importance. As a result of the knowledge gained it is now possible to ‘manage’ the population so as to obtain a maximum return of seal skins, consistent with the maintenance of the population at the necessary level of numbers and condition, at the same time preventing too great an excess which would adversely affect the important fishing interests of the north Pacific. While giving every credit to the ingenuity and skill of the research workers, it must be admitted that several factors have greatly assisted them. The first and obvious one is the economic value of the fur-seal which not only sanctioned the expenditure of money in research, but also provided considerable man-power (non-scientific) for major operations of tagging tens of thousands of the seal pups. The second factor involved is the behaviour of the immature groups which assemble on sites near to the breeding rookeries, segregated into the sexes. The adult bulls and cows too are markedly different in size and pelage and so can easily be distinguished at a distance without the aid of binoculars. Even in the non-breeding season help was available in an extensive pelagic sealing industry over the north Pacific. Nothing comparable is available in the north Atlantic. For all the information available from ships in the North Sea, it might have no seals in it at all, yet we know now that young grey seals cross it regularly and that at certain times of the year the majority of grey seal cows are not in coastal waters. Consequently the pattern set out in detail for the northern fur-seal is of the greatest importance for purposes of comparison wherever possible.

British workers have been responsible for a great deal of work on antarctic pinnipedes such as the Weddell, crabeater and southern elephant seals (Phocidae), the southern sea-lion and southern fur-seal (Otariidae) in the course of the ‘Discovery’ investigations of the inter-war period and of the Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey after the second world war. These researches were undertaken in an attempt to save the natural resources of the southern whale and pinnipede populations. The latter had already been brought to a point of near extinction and the former could easily follow. As a matter of history the pinnipedes have been saved, while the whales have been brought near their end. We were probably right to put our energies into this exercise when we did for not only did it have a happy result for the seals, but we have acquired a national expertise in seals and sealing which is only equalled by that of the United States Fish and Wildlife Service who were responsible not only for the work in the Pribilov Islands, but also for research on the northern elephant seal and other pinnipedes off the Californian coast.

More recently the Canadian Arctic Biological Unit has been formed and is doing good work on seals and walrus off the western north Atlantic seaboard. In the Soviet Union attention has also been turned to this natural resource and work has been done on several species in the north western Pacific Ocean.

In the next chapter we shall see how in the last thirty years or so there has been a considerable growth in the interest shown by both professional and amateur zoologists in Britain in our own species. There has also been expressed a great deal of public concern over the status of our seals but much of this has been ill-informed. The problems are complex and over simplification can lead, as it has done in the past, to harmful action when only good is meant. Intentions are not enough; knowledge is essential.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Полная версия книги