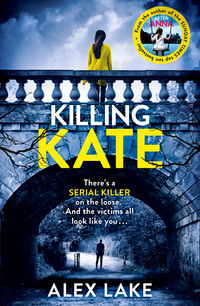

Killing Kate

But God, she was frightened. It was all she could do to stop herself dissolving into a tearful, gibbering wreck.

And then, the lights went out. She looked in the rear-view mirror. The car – a dark saloon of some description – was turning into a residential street, and then it was gone.

She parked by the police station – closed, as she had thought – and dialled 999. The operator picked up and Kate asked for the police.

‘I’ve been followed,’ she said, when the dispatcher came on the line. ‘In my car.’

‘Where are you now, madam?’ asked the dispatcher, a woman with a neutral BBC accent.

‘I’m outside the police station in Stockton Heath,’ Kate said.

‘And can you explain what happened?’

Kate took her through it: the car pulling out, dazzling her with its high beams, and then leaving her alone when she headed for the village.

‘I think he was hoping I’d go home,’ she said. ‘So he could follow me there. I live alone,’ she added.

‘You did the right thing not to return to your residence,’ the dispatcher said. ‘Are you going home now?’

‘I think so. Should I?’

‘That’s up to you. But if you do plan to, let me know. We’ll send an officer round to take a statement. They’ll be with you shortly.’

‘Like five minutes?’

‘Maybe thirty minutes,’ the dispatcher said. ‘And try not to worry. I’m sure it will all be fine.’

‘Thanks,’ Kate said. ‘I’ll meet them there.’ She recited her address, and hung up.

14

She had driven the route from the village to the house hundreds – maybe thousands – of times, but it had never felt like it did this time. It looked the same, but every turning, every house, every alley was now a threat, a possible hiding place for a faceless man who wanted to kill her. As she passed each one she glanced at it, waiting for a car to pull out.

None did.

She parked outside the house. Fortunately, the spot right outside her front door was free so she did not have to walk far from the car to the house. She opened the door and stepped onto the pavement.

And realized someone was watching her.

She didn’t know how she knew, but she knew. She’d read once that the feeling you got when you were being watched or followed was the result of your subconscious picking up clues that your conscious mind didn’t notice. It felt like it was a sixth sense, a paranormal or telepathic ability, but it wasn’t. It was simply that the mind took in a great deal more information than it could process at the conscious level and, when some of that information represented a threat, it made itself known by creating the uneasy feeling of a prickle on the back of the neck that said You are not alone.

Whatever her subconscious had noticed was at the end of the street. There was a large yew tree – some said that it meant there had once been a graveyard there – at the corner, under which there was a bench. It was mossy now, and rotten, so nobody ever sat on it, but there was someone on it now, hiding in the shadows.

She turned and looked. It was hard to make out anything specific, but she was sure that there was a patch of darkness that was darker than the rest, a kind of stillness under the tree which was different from what surrounded it.

‘Who’s there?’ she shouted. ‘Who are you?’

There was no answer. ‘Leave me alone!’ she shouted. ‘I don’t know what you want, but leave me alone!’

The door to the house next door opened. Carl stood there, framed in the light.

‘You OK?’ he said. ‘What’s all the shouting about?’

The relief at seeing him, at not being alone, left her dizzy.

‘There’s someone out here,’ she said, her voice wavering. ‘Under the tree. They’ve been following me.’

‘You sure?’

‘Totally sure. They were driving close to me, flashing their lights. And now they’re stalking me.’

Carl gave her a sceptical look, then shrugged.

‘All right,’ he said. ‘I’ll go and check it out.’

He walked outside. As he did, there was a metallic noise from under the tree, then, seconds later, a hooded figure appeared, pushing a bike. It jumped on and rode away, legs pumping.

‘Bloody hell,’ Carl said. ‘You were right.’

Ten minutes later the police – two male officers, one in his twenties, the other late thirties – were sitting in her front room, taking notes as she told them what had happened. Carl was home; he’d sat with her until they arrived, then left her to it. They were going to talk to him afterwards and get his account.

‘It sounds very unusual,’ the older one said, when Kate had finished. ‘Although we don’t know at this point that the two episodes are linked. It could have been nothing more than an aggressive driver, and maybe a teenager hiding away to have a smoke. You can’t be sure it was the same person both times.’

‘I know,’ Kate said, totally convinced that it was the same person. ‘But what if it is? What if it’s the man who’s killed two young women? If there’s a serial killer out there, I think I need to bear that in mind.’

‘It’s not officially a serial killer,’ the police officer said. ‘We’re still not sure about that.’

‘Serial killer or not, two women are dead,’ Kate said. ‘Which is enough for me. I don’t want to be next.’

‘Of course,’ the younger cop said. ‘We understand that, madam.’

The older officer got to his feet. ‘I think we have all we need,’ he said. ‘There isn’t all that much we can do, I’m afraid. We’ll circulate the details of both incidents to see if they match any others. And I’m pretty sure that a detective is going to want to talk to you about what happened, in case it does have any bearing on the murder investigations. Do you have a number they could call? Perhaps a mobile?’

Kate gave her number. ‘Who should I expect to call? So I know it’s the real thing?’

‘Detective Inspector Wynne,’ the older cop said. ‘It’ll probably be her. And if there’s anywhere you can go tonight – a friend, maybe – you might want to think about doing that. Just in case. It’ll be nice to have company, especially if you’re a bit shaken up.’

‘My parents,’ Kate said. ‘I’ll go to them.’

‘Good idea,’ the officer said. ‘We’ll be in touch if anything comes up, Ms Armstrong.’

Kate showed them to the door. Then she picked up her car keys. There was no way she was staying alone in the house for the night, no way.

15

He couldn’t believe he’d been seen.

He was sure that he was invisible under the tree; he’d looked from every angle before choosing it as his hiding place, but somehow she’d known he was there.

He’d hoped that she would go inside, so he could sneak away, but then Carl – his old neighbour – had come out and he’d had no choice but to flee.

Which meant that he would no longer be able to use the tree if he wanted to watch what his ex-girlfriend was up to. He’d have to find another place to hide, but for the moment he couldn’t think where.

He’d find somewhere, though, if he had to.

He biked along the canal towpath in the direction of the London Bridge pub. He needed a beer to calm his nerves, and maybe a cigarette. It had been years since he’d smoked, but all of a sudden the craving was back.

He had to get a grip of himself. He was falling apart: all day long all he could think of was Kate. He had a constant low-level nausea, a sinking sensation in his stomach that was part anxiety and part disbelief that this was happening. Even worse was the feeling of lacking control; sometimes he felt like he wasn’t himself, that he wasn’t there, that it wasn’t him making decisions.

Like that evening. He’d decided to go and see her after work. He needed to explain what he was going through, not in a desperate, please-have-me-back way, but so that she would know how bad this was for him.

She needed to know: if this was a temporary thing, a break while she lived her life a little, then she had to understand the price he was paying for that break. If it was permanent, then so be it. But they needed to talk.

Except she wasn’t there. And then he started to wonder where she was. Out with someone else? Another man? He couldn’t bear the thought of that, couldn’t accept it. He had to know, and in the end, like an addict with his dope, that need took over.

So he ended up hiding under the tree, waiting for her to come home, imagining her walking down the street with her arm around another man, kissing him on the front step, then unlocking the door and going into the house.

He was frantic the entire time, drumming his fingers on his knees, tapping his shoes on the ground, jiggling his legs, standing up and sitting down. If it wasn’t for the fact that he was hiding, he would have paced the street.

And then she came, alone, and he was caught out, and he fled.

Now it was over, he couldn’t believe he’d done it. Couldn’t believe that he’d acted so crazily. It scared him; the whole thing felt like a dream, like it was a different person. He thought about the time he’d spent under the tree. It was almost like he’d been watching it all unfold, an observer, but now, afterwards, he knew this was not the case. He had done it. He shuddered. It was very troubling.

He walked into the pub and stood at the bar. The pub was warm and busy with the Friday-night crowd. He waited his turn. He ordered a pint of strong bitter and a double whisky, Bells. He felt faint, and dizzy.

The barman looked at him. ‘You all right, mate?’

‘Yeah,’ Phil said. ‘I think so.’

‘You think so? You look a bit pale.’

‘I had a rough day.’

‘All right. Well, let me know if you need anything.’

He paid and took his drinks to a table in the corner. He drank the whisky in one swallow, then swigged the beer.

Even now, he couldn’t stop the thoughts coming. Where had she been? Was she planning on going out tonight? Alone? He wanted to go and see, go and knock on her door and lay himself at her feet, pour out everything he was going through, throw himself on her mercy.

It wouldn’t work. He needed to pull himself together.

But he couldn’t. He knew that she was there, that she was in the house, that she was available. All he had to do was go and knock on the door and he’d be with her. And knowing that – well, it was impossible to resist. He had to go and see her. It didn’t matter if it was a good idea or a terrible idea. He had to do it.

He finished the last of the beer and got to his feet. His legs felt weak, drained. No wonder; he’d barely eaten all week. Most of his calories had come from the wine he’d been drinking himself to sleep with every night.

He got on his bike and retraced the route to their – Kate’s, he had to stop thinking of it as theirs – house. He felt a mounting excitement: for the first time in days he felt almost happy. He was going to see her, face to face. They could sort this out, once and for all.

A few minutes later, he turned into her street, and stopped dead.

There was a police car outside the house.

She’d called the cops. What had she done that for? Because he’d been under the tree? It was a bit of an overreaction, surely. Whatever – he couldn’t go there now.

As he watched, the door opened and two cops came out. He turned and pedalled back towards the pub. The last thing he needed was to be spotted again. He shook his head. Seeing the police at the house brought things into focus: this wasn’t a game.

He had to stop this. He absolutely had to stop this.

The only problem was that he wasn’t sure he could.

16

Her parents, of course, overreacted.

‘Move in with us,’ her mum said. ‘Don’t go back to that house. You mustn’t go back there. It’s not safe.’

‘It’s perfectly safe,’ Kate said, her teenage self bridling at her mum’s attempt to limit her freedom, to suggest that she couldn’t take care of herself.

‘Then why are you here?’ her dad said. ‘Your mum has a point, Kate.’

‘I need to stay tonight,’ Kate said. ‘That’s all.’

Her dad didn’t reply, which was what he did when he didn’t agree but didn’t want to say so and risk being accused – as he often had been – of imposing his views on everyone else. He was a man of strong opinions, and at some point had realized that one of his more unattractive traits was his inability to change them. In an attempt to mitigate this, he had developed the strategy of remaining silent when he disagreed with someone, which, in many ways was worse. Kate had been on the receiving end many times. She remembered when she had declared that she was planning to buy her Mini, a plan that required getting a car loan.

You should never borrow to buy something, unless it’s a house, her dad said.

Dad, it’s fine. Everyone does it. I can afford the payments.

No response. Not a Well, I’m sure you’ll be OK, no doubt you’ve thought it through. Just silence, which – ironically, since it was an attempt to say nothing – said a great deal. It said You’re totally and utterly wrong and probably not even functionally intelligent, but it’s your funeral and don’t come crying to me when it all goes to hell in a handbasket.

Which was what the silent treatment she was now getting meant. Fortunately, her mum had no such inhibition about expressing an opinion.

‘No,’ she said. ‘You’re staying here. And that’s it.’

‘We’ll talk more tomorrow,’ Kate said. ‘But I’ll probably get Gemma to stay with me, or something like that.’

Her mum shook her head. ‘Under no circ—’

‘Mum!’ Kate said. ‘Please!’

‘I’m only trying to do what’s best for you, darling.’

‘I know, and I’m grateful. But can we discuss this later? I’m tired. I think I’m going to go to bed.’

‘Do you want something to eat?’ her mum said, which was her default question.

‘A drink?’ her dad said, which was his default question. ‘There’s white in the fridge. I think there’s a red open as well.’

‘No thanks,’ she said. ‘I think I’ll have a bath, then bed.’

Lying in the bath, she googled serial killers. There was a lot of material out there on them. She scanned it, clicking between websites. It varied, but there were some key themes, one of which she found particularly troubling.

There was, a lot of experts claimed, a strong ritualistic element in the activities of most serial killers. Often they were repeating the same murder over and over, each time trying to perfect it, each time getting a greater and greater thrill from it.

There were other themes that emerged: many serial killers liked to engage in a game of cat-and-mouse with law enforcement agencies – often trying to insert themselves into the investigation in some way – in an attempt to prove their superior intelligence; the level of violence towards the victims often increased as the killer’s confidence grew; the serial killer would purge the desire to kill before it started to build again to the point where they needed release.

But the one that stuck with her was the presence of ritual.

Was the appearance of the victims part of the ritual in this case? She wasn’t sure, but it certainly seemed possible.

Which gave her an idea. A way to put a stop to all this.

The next morning she made some phone calls. Most places were busy, but eventually she found one that had an open slot.

‘Mum,’ she called, sipping the last of her tea. ‘I’m just popping out. I’ll be back for lunch.’

Her mum came into the kitchen.

‘Where are you going?’

‘Out. And then at three I’m meeting Gem to go to the Trafford Centre.’

‘But where are you going now?’

She didn’t want to tell her mum. She couldn’t face the conversation, didn’t want to have to explain what she was doing and then listen to her mum’s objections. It was easier to do it and deal with the fallout later.

Gemma had a saying: Beg forgiveness, don’t ask permission. Kate thought it applied here.

‘Out. Maybe go grab a coffee somewhere. But mainly anything to get out of the house.’

‘Go and grab,’ her mum said. ‘Not go grab. You aren’t American, darling. I know you like to watch those television shows, but you don’t need to speak like them.’

God, her mother annoyed her sometimes.

‘And anyway,’ her mum continued, her expression sceptical. ‘You had a cup of tea five minutes ago.’

‘Mum! I’m old enough to go out for a coffee!’

‘I’ll come with you. I could do with an outing.’

‘Mum, please. I’m only popping out. OK?’

Her mum shrugged, evidently not believing a word she said. ‘See you at lunch, then.’

She was back shortly after midday. Her dad was sitting in the living room, watching the news. She walked in and stood, waiting for his reaction. He studied her before he spoke.

‘Bloody hell,’ he said. ‘Bloody hell.’ He called into the kitchen. ‘Margaret, come and see your daughter.’

Her mum appeared in the door frame. She blinked a few times, then smiled.

‘Gosh,’ she said. ‘That’s quite a change.’

17

It was. Kate had explained what she wanted to the hairdresser; he had asked if she was sure, absolutely sure, and she said yes, she was. So he went ahead. He cut her long, black hair into a close-cropped fuzz, which he dyed a dark red.

She hated it. Hated seeing her hair on the floor, hated how big her head looked, hated seeing herself shorn in this way. She was not vain, but she had always been proud of her hair. She had been told a million times that it was gorgeous and lovely and the compliments had stuck. Some portion of her self-esteem was wrapped up in her hair, and now it was gone. But she had a good reason for having done this, and, when it was safe to do so, she could always grow it back.

On her way home she went to a costume shop. It was a place she’d used before, when she and Phil had gone to a Halloween party in fancy dress. That time she’d bought bright red contact lenses; this time, she got green ones.

With them in she looked nothing like herself. More importantly, she looked nothing like Jenna Taylor or Audra Collins.

Gemma’s reaction was far less muted than her parents’ had been. She screamed, clapped her hand over her mouth, then burst into laughter.

‘Oh. My. God!’ she said. ‘What have you done?’

‘That’s a nice reaction,’ Kate said. ‘Don’t you like it?’

‘I dunno,’ Gemma said. ‘I suppose so. It’s – well, it’s a pretty big change, Kate. It’s not your usual style. It’s not what you do. I mean, it’s kind of like if Kate Middleton did it. A bit of a surprise.’

‘I know,’ Kate said. ‘And I hate it. Not as much as I did this afternoon – I suppose it’s growing on me …’

‘Literally,’ Gemma said. ‘Although it’s still got some growing to do.’

‘… But I have my reasons.’ She took out her phone and typed a search into Google. A picture of the two murdered women came up. ‘They look like me,’ she said, handing her phone to her friend. ‘Remember you guys teasing me about that? We laughed, but it’s not so funny now.’

Gemma studied it for a second or two. When she looked at Kate she was pale.

‘They don’t look like you now,’ she said.

‘Right,’ Kate said. ‘And it’s going to stay that way until this is over.’

They spent the afternoon at the Trafford Centre. Kate had never noticed before, but it was a place that, between the glass shopfronts and the mirrors inside the shops, was full of reflections. She saw herself everywhere, saw this stranger with the short, red hair and green eyes walking side by side with the familiar form of her friend, and each time was surprised anew at the realization that it was her.

It was interesting to see how the shop assistants treated her. When they suggested clothes for her they were different to the clothes she was used to being offered: more urban, more punk, more edgy.

She wasn’t quite ready to embrace her new style fully yet, not least because those scruffy-looking punk clothes came at designer prices. It cost as much to dress down as to dress up.

She was glad, though, that they saw her that way. It meant that the transformation had been a success. Whatever the type was that the killer was targeting, she no longer fit it.

That evening they went out for dinner, and then for a drink at a wine bar. Gemma had agreed to stay over, and they had drunk a bottle of wine with their meal. They were now drinking gin and tonics, and Kate was feeling the effects.

It was a nice feeling, though. Relaxing and warm. A great way to end a difficult week.

‘Well,’ Gemma said. ‘I’m starting to get used to your new look. And I have to say, I kind of like it.’

‘You’re only saying that,’ Kate replied. ‘And there’s no need. This is temporary. You don’t have to make me feel good about it.’

‘I’m not, I promise. It’s cool. And you’re so pretty that you can get away with it. Especially with those green eyes. I might get some myself.’ She sipped her drink; it was getting low. ‘One more?’

‘Why not?’ Kate stood up. ‘It’s my round. And I need the loo.’

In the Ladies she used the toilet, then, after washing her hands, took a small bottle of eye drops from her purse. The contact lenses were irritating her eyes. She wasn’t used to wearing them and she was looking forward to taking them out when she got home.

She stared at herself in the mirror. It was like looking at a different person. She smiled, and headed to the bar.

As she waited her turn, someone bumped into her back.

‘Sorry,’ a voice said. ‘Excuse me.’

The voice was familiar, and she turned round. It took her a moment to realize who it was.

It was Mike, the guy from Turkey.

‘Sorry about that,’ he said. ‘It’s a bit of a tight squeeze.’

She grinned; it was clear he didn’t recognize her, which was exactly what she wanted. ‘That’s fine,’ she said. ‘No problems.’ Then she added: ‘Mike.’

He paused. ‘Do I know you?’ he said. He stared at her, then his mouth opened. ‘No way,’ he said. ‘It’s you! It’s Kate?’

It was half-question, half-exclamation.

‘That’s right,’ she said. ‘How’ve you been?’

‘Great,’ he said. ‘Same as usual. Nothing new.’ He gestured at her hair. ‘Can’t say the same for you. It looks great, by the way. You look great.’

‘Thanks, but I didn’t do it for looks.’ The wine and the gin and tonic were making her more loose-lipped than usual. ‘I did it for tactical reasons.’

‘Oh? Like what? You joining the SAS?’

She laughed. ‘No, not exactly. It’s kind of a disguise.’

‘It’s a pretty good one. Can I ask why?’

She took out her phone and showed him the picture she’d showed to Gemma earlier.

‘Wow,’ he said. ‘I see. Good idea. It’s a bonus that it looks pretty awesome too.’

‘That’s kind of you to say. Anyway, what are you doing here?’

He pointed to a group of men at the end of the bar. ‘Cricket club. I used to play and I came to watch a game today. Been having a few beers with the boys.’ He looked at his watch. ‘But I have to go.’

‘Hot date?’ She was surprised at her forwardness; maybe she’d think again about another drink.

‘Something like that.’

She was intrigued to find that she was – a little – jealous.

‘Well,’ she said. ‘Enjoy. And I’ll maybe see you around?’

‘Yeah,’ he said. ‘See you around.’

When she got back to the table, Gemma gave her a knowing look. ‘Was that who I think it was?’

‘Who do you think it was?’

‘The guy? From Kalkan? What was his name?’

‘Mike. And yes, it was. And guess what? He didn’t recognize me.’

‘He’s kind of cute. In an older way.’ She raised an eyebrow. ‘And you obviously thought so when we were on holiday.’

‘He’s OK. But I’m not interested. Not at the moment.’