Nein!

A new myth – that of the ‘stab in the back’ – began to be promulgated by the German right. This blamed ‘the politicians’ for the defeat of 1918 and the Versailles humiliations that followed. It was claimed that the German army was undefeated, but had been betrayed by the politicians in Berlin who signed the Armistice. It was not long before the Jews were added into the mix, which swiftly mutated into an international conspiracy aimed at the destruction of Germany and its people. The ‘stab in the back’ legend became so deeply imbedded in the German pre-war psyche that it would restrain Hitler’s domestic opponents, and influence the Allies’ terms for peace, right up until the end of the coming war.

Between 1924 and 1929 the German economy stabilised, thanks in large measure to US loans. A period of great artistic renaissance followed. Berlin, reverberating to the talents of Thomas Mann, Bertolt Brecht, Max Reinhardt, Marlene Dietrich and the artists and architects of the Bauhaus movement, became the cultural capital of the world.

No sooner was hope reborn than it was broken again on the wheel of a second economic crisis, this time brought about by the Wall Street crash of October 1929. By 1932, with unemployment standing at six million, those, including dependants, directly affected by loss of work amounted to 20 per cent of the German population.

Revolt was once again in the air. Running battles broke out in the streets between communists and Hitler’s stormtroopers. A German commentator on these years wrote, ‘In [these] times, principles are cheap and perfidy, calculation and fear reign supreme.’

These were perfect hothouse conditions for the growth of the most radical forms of extremism. Driven by a mystic and misshapen belief in the moral rebirth of Germany, unencumbered by doubt, unheeding of convention, fed on hate, armoured with conspiracies and slogans and led by a messianic leader who combined charisma with an astonishing ability to move the masses, the Nazi Party’s time had come. In the 1928 elections, the National Socialist Democratic Party – known by its shortened version, ‘Nazi’ – was no more than a tiny fringe party winning only 2.6 per cent of the vote. Just four years later, in July 1932, Hitler’s party secured 13.7 million votes, making it, with 37 per cent of the national vote, by far the largest party in the German Reichstag. A second national election in November of that year saw a drop in the Nazi vote. Nevertheless, after a period of parliamentary stalemate, the ageing German president Paul von Hindenburg appointed Hitler chancellor in 1933, believing that this was the best means to control him. ‘We’ve engaged him for ourselves,’ said former chancellor Franz von Papen, one of the grandest of the grandees in German politics. ‘Within two months we will have pushed Hitler so far into the corner that he’ll squeak.’

By these miscalculations the nation of Beethoven and Schiller, of Goethe and Schubert, was given over, lock, stock and barrel to the most primitive, destructive and primeval force for barbarism that Europe had seen since the Dark Ages.

While most of the elite saw Hitler as a harmless eccentric who they could control and who would not last for long, many ordinary Germans, even those who did not vote for him, believed that he might represent a new start and should be given a chance – after all, many argued, things couldn’t get worse, could they?

All of them had misjudged their man.

Adolf Hitler was remarkable in many ways. He was always thinking the unthinkable; always proposing the objectionable; always choosing to shock, rather than to comfort; always rejecting the constraints of convention; always preferring myth and mission to reality; always taking people by surprise with his undiluted radicalism; always trusting his own inner voice in preference to facts and other people’s opinions. ‘I confront everything with a tremendous ice-cold lack of bias,’ he once declared. Because a thing should be, it would be – that was Hitler’s doctrine. On the altar of this absolutism, bolstered by his much-vaunted ‘triumph of the will’, Hitler would lay waste to half of Europe.

But it was not these manic qualities which made Adolf Hitler different. What distinguished him from the many other fascist leaders of his age, and from the myriad self-declared prophets of history, was his genius for political action – he was a mythmaker with a practical understanding of power and how to use it to achieve his ends.

It was this, more than anything else, which caused friend and foe alike to look upon him with a wonder which produced adulation, fear and intrigued curiosity, depending on where you stood in relation to his power.

Foreign capitals, blindly hoping to ‘tame the beast’ who would not be tamed, proposed the usual well-tried European inducements of agreements, pacts, bribes and appeasements in the vain hope of containing the uncontainable. The whole of Europe was mesmerised – paralysed too – by what had happened in Berlin. A German observer in Paris noted among the French ‘a feeling as if a volcano has opened up in their immediate vicinity, the eruption of which may devastate their fields and cities any day. Consequently they are watching its slightest stirrings with astonishment and dread. A natural phenomenon which they are forced to confront … helplessly. Today Germany is again the great international star that appears in every newspaper, in every cinema, fascinating the masses with a mixture of fear and reluctant admiration … Germany [under Hitler] is the great, tragic, uncanny, dangerous adventurer.’

Inside Germany, it did not take long for those who disagreed with Hitler to find out that things could get worse – very much worse.

The first underground opposition to the Nazis grew out of a combination of political groupings which had stood against him in the elections – chiefly the communists and the Social Democrats.

Tainted by their association with the failures of the Weimar Republic, and in the case of the communists by their refusal to join an alliance against Hitler during the economic crises of 1930–33, Hitler’s democratic opponents were easily outmanoeuvred and broken by his ruthless pursuit of power.

Like so many others at home and abroad, Germany’s conventional parties failed to recognise the uniqueness of Hitler’s demonic nature, and presumed that his revolution was just another episode in the normal rhythms of the democratic cycle. ‘Harsh rulers don’t last long,’ said the chairman of the last great Social Democratic Party rally in Berlin in 1933.

A terrible price would soon be paid for this apathy.

On 22 March 1933, just seven weeks after Hitler became chancellor, the first concentration camp opened its gates to admit two hundred political prisoners to an old gunpowder and munitions factory which SS leader Heinrich Himmler had chosen at Dachau, sixteen kilometres from Munich. The camp, with its gates bearing the infamous legend ‘Arbeit macht frei’ – Work will make you free – would remain a byword for torture, every kind of inhumanity and mass extermination, until it was overrun by American troops in the last year of the war. By the end of 1933, 20,000 of Hitler’s political opponents were either in jail or doing their best to survive under the most brutal conditions in Dachau and other concentration camps, now popping up across Germany.

Despite violent anti-communist purges, which started very soon after Hitler became chancellor, communist cells began to reseed themselves in factories and workplaces. Mostly these numbered no more than six or eight people, connected by a sophisticated courier system to other cells, the identities of whose members they often did not know. These networks extended into other European countries, where they were especially active in German émigré communities. In due course, after a brief period of quiescence during the Nazi–Soviet Non-Aggression Pact, and despite being energetically pursued by Hitler’s secret state police, the Gestapo, the German communist underground network would turn to sabotaging the war effort and spying, not least through the great Russian wartime spy network which operated throughout occupied Europe, nicknamed by Himmler’s security structures die Rote Kapelle (the Red Orchestra).*

What was left of Hitler’s political opposition went underground. Among the German resistance’s early supporters were numerous activists in the social democrat cause and many in the trade union movement.

Opposition to Hitler was not confined to the workers. Although some German industrialists and financiers, such as Alfred Krupp, found good commercial reasons to support Hitler, a number of others, like the great engineering industrialist Robert Bosch in Stuttgart, courageously provided active succour to the opposition.

With the communists, liberals and social democrats forced underground, it was left to some elements of the German Church to nurture popular opposition to National Socialism. The Barmen synod of May 1934 in Wuppertal brought together Lutherans who openly condemned the materialism and ungodliness of National Socialism, attracting tens of thousands from all over Germany to an open-air demonstration at which they voiced their opposition to what was happening. In the St Annen-Kirche in the Berlin suburb of Dahlem, the middle class thronged to hear ‘the fighting pastor’ Martin Niemöller preach his incendiary sermons against all the Nazis stood for. In southern German cities like Nuremberg, Stuttgart and Munich, Christians marched in the streets in support of Lutheran bishop Theophil Wurm and his colleague Hans Meiser, bishop of Munich, both of whom had been placed under house arrest for inciting public disturbance. An anti-Nazi tract written by Helmut Kern, a Lutheran pastor from Nuremberg, sold 750,000 copies in short order – the highest circulation for a religious tract since those of Luther himself.

Hitler, despite his by-now unchallenged dominion over the instruments of the German state, shrank from open warfare with the mass ranks of the German Churches, Protestant and Catholic. But he tried every other means to suppress the dissent. Niemöller was arrested and sent to a concentration camp, from which he did not emerge until the war was over. Troublesome pastors were conscripted en masse into the army, the Church’s work with the young was curtailed, teaching permits were withheld for those lecturing in theology at German universities, and permission was refused for the publication of all pamphlets except those acceptable to the Nazi regime. Hitler’s supporters even managed to infiltrate the Church elections of July 1933 to such an extent that he was able to enforce the anti-Semitic ‘Aryan Law’, removing all pastors who were ‘tainted’ by descent from Jewish or half-Jewish forebears.

On 14 March 1937, Pope Pius XI issued a powerful encyclical attacking the new wave of ‘heathenism’ in such strong terms that it became a call to arms against the Nazis. What followed was an open and violent counterattack on the monasteries, led by Hitler’s minister of propaganda Joseph Goebbels. In a purge reminiscent of Henry VIII, some were commandeered for military bases, others were banned from accepting new entrants or holding religious processions. Between 1933 and 1945 thousands of brave pastors and friars were to be found among the inmates of the concentration camps, where many of them lost their lives as martyrs for their beliefs.

Although Hitler was finally able to stem ‘the mischief-making of the Church’, religion and religious activists, including the great pastor, theologian and spy Dietrich Bonhoeffer, played a huge part in providing the inspiration, moral underpinning and manpower for the anti-Hitler resistance.

Scattered amongst these organised and semi-organised structures of the German resistance were a number of individuals who, as the excesses and horrors of Nazism became more and more evident, started to wage their own private and lonely struggles against the Nazi state. Among these were the Württemberg carpenter Georg Elser, who, acting entirely alone, missed assassinating Hitler with a bomb by a hair’s breadth because of fog at Munich airport; Otto and Elise Hampel, who distributed over two hundred anti-Hitler messages around Berlin and died under the guillotine as a result, and the students of the White Rose Circle who, led by their tutor, met the same fate for distributing pamphlets around Munich.

These remarkable individuals – Auden’s ‘ironic points of light’ – ignited brief beacons of moral courage in the darkness. But they did not – could not – alter the course of the war.

As they, and many we do not know of, changed their stance from supporting Hitler to actively opposing him, others in the most senior echelons of the Nazi state were tracing similar paths towards their own individual epiphanies.

Chief among these were three men: a civilian who could have been chancellor in Hitler’s place; a general who many believed was destined to lead his armies; and the head of his foreign intelligence service.

* Literally ‘the Red Chapel’. In this usage the word ‘Kapelle’ is meant to indicate that it is a secret organisation. The translation of ‘Kapelle’ as ‘orchestra’ is capricious and confusing. ‘Ring’ would have been better.

1

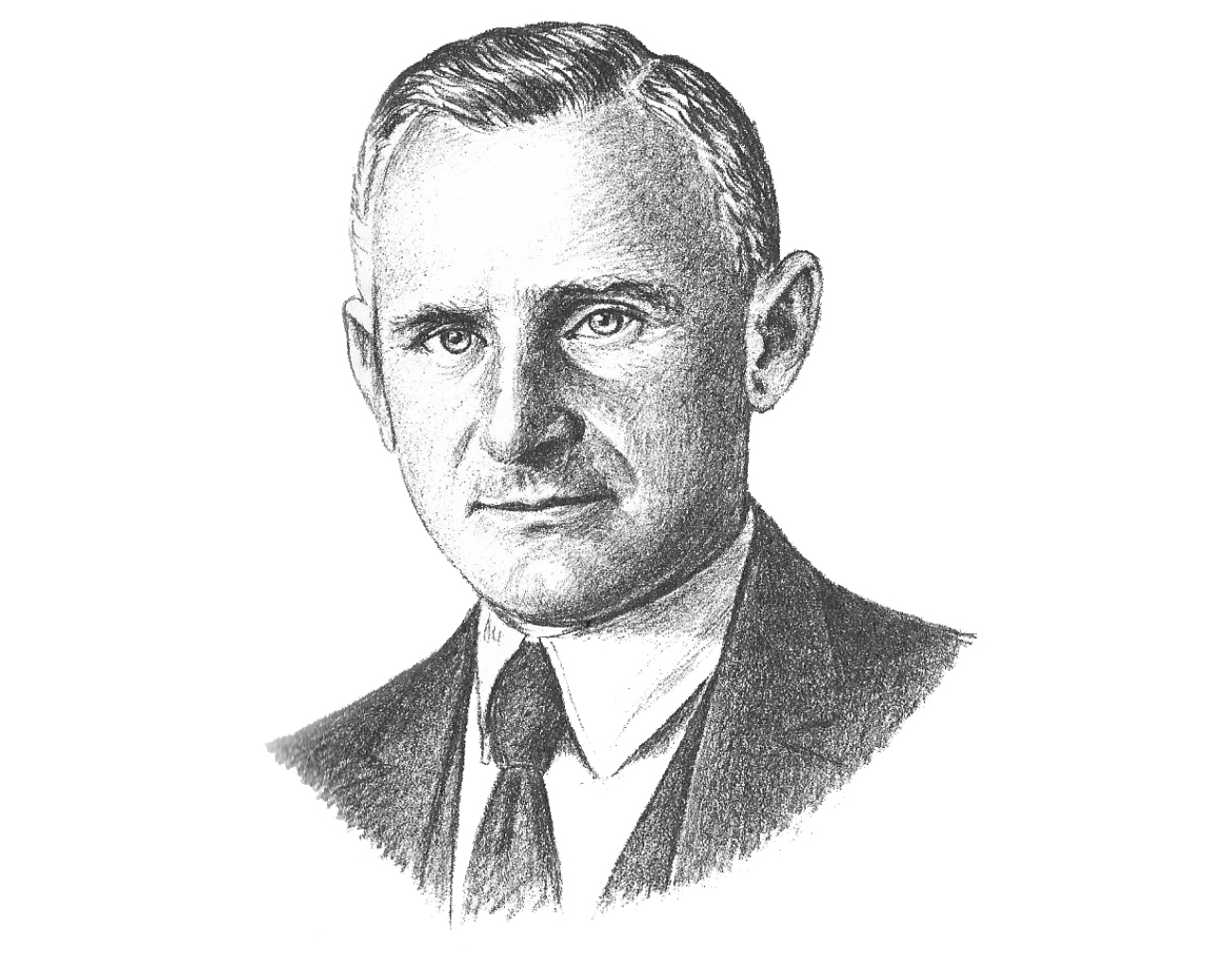

Carl Goerdeler

Late-evening sunlight streamed through the Palladian windows of the dining room of the National Liberal Club in London. It fell on a damask tablecloth laid with silver and porcelain in a secluded alcove set slightly apart from the other tables. The wooden panels all around glowed a deep mahogany, and the air resonated with the low murmur of diners enjoying themselves, despite the stern gaze of William Gladstone’s twice-life-size statue at the far end of the room.

The six men at the alcove table were not cheerful. They were sombre, quiet-voiced, and listening carefully to one of their number, an imposing figure with boyish good looks, startling light-grey eyes, heavy eyebrows and a forceful personality. The fifty-two-year-old Carl Goerdeler was a serious man who was used to being taken seriously. Ex-lord mayor of the great German city of Leipzig, until recently a key official in the government of Adolf Hitler and a sometime candidate for chancellor of Germany, Goerdeler was a dinner guest whom it was easier to listen to than to converse with.

Born on 31 July 1884 in the west Prussian town of Schneidemuehl, Carl Friedrich Goerdeler, the son of a district judge, had been a brilliant student at school, a brilliant law graduate at Tübingen University, and by all accounts a brilliant practising lawyer before finding his metier as an economist and senior official in German local government. He soon proved a talented and effective administrator, whose grasp of economics, incorruptible personality and ability to charm were quickly recognised. In 1912, at the age of just twenty-eight, Goerdeler was unanimously elected as principal assistant (effectively deputy) to the mayor of the Rhenish town of Solingen in western Germany. His military service on Germany’s Eastern Front in the First World War ended with a period as the administrator of a large swathe of territory in present-day Lithuania and Belarus which had been occupied by Germany under the terms of the Brest-Litovsk Treaty of 1918. Here he added a reputation for humanity and compassion to his other recognised virtues.

The Armistice in November 1918 changed everything for Goerdeler, and for Germany. Like most Germans, he felt that his country’s emasculation in the Versailles settlement inflicted a deep shame and injustice on his Fatherland. It was in these post-war years that Goerdeler the nationalist and patriot began to take form. The brutal amputation of Danzig from the ‘motherland’, in order to give newly-enlarged Poland a corridor to the sea, especially offended his sensitivities, both as a German and as a Prussian. He maintained a vocal opposition to this Versailles humiliation long after most other civil and military leaders had accepted the necessity to move on. This was as admirably fearless as it was tactically stupid. It was also an early example of a stubborn refusal to compromise when Goerdeler considered his cause just, which would become a leitmotif of his life until the very end.

By now Goerdeler’s political views had solidified. He was by upbringing a devout Lutheran, and by political conviction a conservative with an attraction to constitutional monarchism. He was authoritarian, patriotic, consumed by a belief in the power of political ideals and democracy (but only to the point where these did not interfere with efficient government). Economically, he believed in financial rectitude; in his dealings with others he was punctilious, in his personal habits he was frugal, and in his personal life he was guided by an unyielding moral code which even extended to refusing entry into his family home to those who had been divorced. One of his friends, and a future fellow plotter against Hitler, wrote: ‘Goerdeler was a clear-headed, decent, straightforward kind of man who had very little or nothing about him which was sombre, unresolved or enigmatic. He therefore assumed his fellow human beings needed only enlightenment and well-meaning moral instruction to overcome the error of their ways.’

These qualities would have made Carl Goerdeler a great man in any stable age, but they rendered him a hopelessly naïve utopian in the cruel age of turbulence and revolution in which he had to live his life.

After a period as the deputy mayor of Königsberg on the Baltic coast during the 1920s, Goerdeler was elected Oberbürgermeister (lord mayor) of Leipzig in 1930, just two months before his forty-sixth birthday. Now he was a big figure on the national stage. At the time he took over the Leipzig administration, Germany was midway through its second great economic convulsion, following the hyper-inflation of the early 1920s. In December 1931, with unemployment rocketing, Goerdeler accepted an invitation from President Hindenburg to join his government as Reichskommissar (State Commissioner) for price control. His deft handling of this delicate role earned him widespread acclaim. When Hindenburg’s chancellor, Heinrich Brüning, resigned in May 1932, Goerdeler was widely thought of as his successor. But the political turmoil which ensued did not produce a man of rectitude and order – it produced instead Adolf Hitler, who became chancellor of Germany on 30 January 1933.

Carl Goerdeler

Goerdeler did not at first oppose Hitler. He saw the new chancellor as potentially an enlightened dictator, who with the right advice could be a force for good and for order after the upheavals and failures of the Weimar years.

It did not take long for the scales to fall from the lord mayor of Leipzig’s eyes.

On 1 April 1933, when the city’s Jewish businesses were threatened by Nazi stormtroopers of the Sturmabteilung (SA) during Hitler’s ‘day of national boycott’, it required an appearance by the mayor in full ceremonial dress, backed by the police, to save the situation from descending into violence and calamity. There followed several instances when Goerdeler had to intervene personally to save Jewish enterprises from the consequences of Hitler’s policy of sequestrating Jewish assets and businesses in order to ‘Aryanise’ the German economy.

There was worse – much worse – to come. On 30 June 1934 Hitler launched the internal putsch which history has come to know as the Night of the Long Knives. The ostensible purpose of this act of national bloodletting was to exterminate the paramilitary SA, which Hitler saw as a growing threat to his power. But the killings extended into a general orgy of score-settling with enemies of the Nazi regime. Among the eighty-five killed were the army general who was Hitler’s immediate predecessor as chancellor, the personal secretary of another chancellor, and several Catholic political leaders. It was now plain to all that Hitler’s government was prepared to behave illegally, unscrupulously, murderously, and completely without reference to either moral or legal codes. This was a turning point for many.

But not, despite all his moral rectitude, for Carl Goerdeler.

On 5 November 1934, barely four months after the Night of the Long Knives, Goerdeler accepted an offer from Hitler to become, for the second time, Germany’s commissioner for price control. His decision to serve Hitler at this time was one he would find difficult to explain later. Why did he do it? The answer provides keys to two of the most puzzling paradoxes of Goerdeler’s complex personality. Alongside an all-consuming conviction of what was right and wrong, including a willingness to accept any personal sacrifice rather than to submit, he also possessed an almost childlike ignorance about the true nature of evil. Because of this, despite his worldly wisdom in matters of politics, government and the economy, he completely overestimated his ability to persuade bad men to do good things, by talking sensibly to them.

The truth was that Goerdeler accepted Hitler’s post because he believed he could change him. His chosen weapons for doing this were a stream of long (in some cases very long) memoranda and papers on the economy, directed at the chancellor. These were read either skimpily or not at all. Following a succession of turf battles and disagreements on public policymaking, the inevitable rupture between the two men occurred in 1936, when Goerdeler lost all power and influence in Hitler’s circle.

This was the moment for which the lord mayor’s Nazi enemies in Leipzig had been waiting.

In early November that year, the Oberbürgermeister was invited to speak at the German-Finnish Chamber of Commerce in Helsinki. At the time Goerdeler was under attack by the local Leipzig Nazi leader because of his refusal to remove the statue of Felix Mendelssohn, the great German-Jewish composer, from its position outside the city’s concert hall. Pointing out the statue to a visitor, the Oberbürgermeister complained: ‘There is one of my problems. They [the Brownshirts] are after me to remove that monument. But if they ever touch it I am finished here.’ To his daughter Marianne he seems to have indicated that what really affronted him was an outrageous attack not so much on a Jew, as on German culture: ‘All of us listened to Mendelssohn’s songs with great pleasure and sang them as well. To deny Mendelssohn is nothing, but an absurd, cowardly act.’

Before leaving for Helsinki, Goerdeler extracted promises from Hitler and Himmler that they would personally ensure the safety of the statue in his absence. Nevertheless, the local Nazis pulled it down while he was away. Returning to Leipzig in a fury, Goerdeler issued an ultimatum that the missing statue should be replaced forthwith. When it wasn’t, in typical Goerdeler style, he resigned. It should be noted that his resignation was far more a protest against the loss of his authority than against anti-Semitism, for his position on the Jews at this time was at best ambivalent. Even so, for this act of principle against tyranny and of protest against an outrage to German culture, Carl Goerdeler became an overnight hero to many across Germany who saw him as having sacrificed his public career rather than lend his name to a shameful deed.

As the bearer of all that was good and great about German culture, order and respect for the law, Goerdeler, who never liked to be without a mission for long, now decided that personal responsibility and conscience demanded that he should henceforth dedicate his superhuman energy, ability and moral purpose to a single end – the removal of Adolf Hitler.

His first task was to warn the world about the true nature of the German dictator and the threat that he posed. But how? Goerdeler was, after all, not only without a job, but also without a passport, which had been confiscated by a local Gauleiter.

What he needed for his new mission was money, and his passport back.

The money came from Robert Bosch, the head of the Bosch industrial empire and leader of a small group of Stuttgart democrats who were hostile to Hitler. Bosch appointed Goerdeler (who had already turned down a post with Alfred Krupp, a man of very different political views) as financial and international adviser to his firm, so providing him with both a reason to go abroad and a comfortable salary to live on.