Nein!

This time, Colvin’s meeting with von Kleist-Schmenzin took place not in a well-known Berlin club, but in a dimly-lit backstreet bar in Bendlerstrasse, close to army headquarters. The German had something important to say ‘in a few short sentences, any one of which would have been enough to send him to instant execution’. Kleist-Schmenzin informed Colvin of the purpose of his forthcoming visit to the British capital: ‘The Admiral [Canaris] wants someone to go to London … We have an offer to make to the British and a warning to give them.’ That night Colvin wrote from the Adlon Hotel to his fellow journalist and friend, Winston Churchill’s son Randolph: ‘A friend of mine will be staying at the Park Lane Hotel from the 18th to the 23rd. I think it essential he should meet your father. Please put nothing about him in your column or mention him to any of your colleagues. The visitor will have information of great interest to your father.’

On his arrival at Croydon Aerodrome, Kleist-Schmenzin was observed to board a coach for London, where he booked into the Park Lane Hotel. The following afternoon the German visitor, describing himself as ‘a conservative, a Prussian and a Christian’, met Sir Robert Vansittart for tea – ‘[But not] I need hardly add … at the Foreign Office,’ Vansittart was careful to explain in his subsequent report.

The Foreign Office mandarin was impressed with Kleist-Schmenzin: ‘He spoke with the utmost frankness and sincerity … [He] has come out of Germany with a rope around his neck, staking his last chance of life on preventing [the war],’ he reported, adding: ‘Of all the Germans I saw, Kleist had the stuff in him for a revolution against Hitler.’

Over tea, Kleist-Schmenzin told Vansittart that war was now ‘a complete certainty’ unless Britain acted. ‘Hitler has made up his mind … the mine is to be exploded [after 27 September] … All [the generals] … without exception … are dead against the war. But they will not have the power to stop it unless they get encouragement from outside. We are no longer in danger of war, but in the presence of the certainty of it … [But if Britain acted to defend Czechoslovakia] it would be the prelude to the end of the [Hitler] regime. [His army friends were unanimous] … they had taken the risk and he had taken the risk of coming out of Germany at this crucial moment … but they alone could do nothing [if Britain did nothing].’

The following day, 19 August, Kleist-Schmenzin was driven south through the ripening fields and orchards of Kent to Chartwell House, where Winston Churchill, out of government, was struggling to catch up on a missed deadline for his magnum opus, A History of the English-Speaking Peoples. The two met that afternoon in the room Churchill had set aside for important visitors. It was a space that would have been very familiar to a Prussian with an ancient lineage, with its heavy dark-oak carved furniture and Gothic-style beamed ceiling hung with a banner bearing the Churchill coat of arms. In one corner, where the sunlight streamed through a south-facing latticed window, was a table cluttered with family photographs. Close by, two comfortable chairs were drawn up in front of an Elizabethan fireplace. Churchill’s son Randolph sat to one side on an upright chair, taking notes in shorthand.

‘Kleist started by saying that he thought an attack on Czechoslovakia was imminent and was most likely to occur … [before] the end of September,’ Randolph scribbled. ‘The generals are for peace … and … if only they could receive a little encouragement they might refuse to march … Particularly was it necessary to do all that was possible to encourage the generals who alone had the power to stop war … In the event of the generals deciding to insist on peace, there would be a new system of government within forty-eight hours … [which would] end the fear of war.’

Winston Churchill understood very well what Kleist-Schmenzin was telling him. He would later write: ‘There can be no doubt of the existence of a plot … and of serious measures taken to make it effective.’

Kleist-Schmenzin seems to have asked Churchill for a personal assurance he could take to Ludwig Beck in Berlin that Britain would act militarily if Hitler attacked Czechoslovakia, for at one point Churchill broke off the conversation to ring Halifax. The foreign secretary agreed the outlines of a letter which Churchill could secretly send to Kleist-Schmenzin in the near future, to ‘re-assure his friends’ that Britain would defend the Czechs.

Travelling back to London through the failing light of an English summer’s evening, with Churchill’s promise ringing in his ears, Ewald von Kleist-Schmenzin must have felt that his dangerous trip had been worth it – he had what Beck and his friends in Germany had asked him to get: a clear commitment that London would act if Hitler moved against Czechoslovakia. Now they could get on with planning the coup to remove the dictator and prevent the coming war.

The next day, Churchill sent the record of his meeting to prime minister Chamberlain, foreign secretary Halifax, Halifax’s predecessor Anthony Eden, and shortly afterwards to the French prime minister, Édouard Daladier.

Chamberlain was again dismissive. In a note to Halifax he wrote that Kleist-Schmenzin and his friends ‘remind me of the Jacobites at the Court of France in King William’s time and I think we must discount a good deal of what he says’. But a double negative in the last sentence of the prime minister’s minute seems to betray some uncertainty: ‘Nevertheless I confess to some feeling of uneasiness and I don’t feel sure that we ought not to do something … Inform [Sir Nevile] Henderson … and tell him … to make some warning gesture.’

A few days later a diplomat at the British embassy in Berlin discreetly slipped an unaddressed envelope to Ian Colvin, who passed it on to Kleist-Schmenzin in the backstreet bar in Bendlerstrasse where the two men had met before the German emissary’s departure for London.

Inside the envelope a letter from Churchill read:

My Dear Sir,

I have welcomed you here as one who is ready to run risks to preserve the peace of Europe … I am sure that the crossing of the frontier of Czecho-slovakia … will bring about a renewal of the world war. I am as certain as I was at the end of July 1914 that England will march with France and … the United States … the spectacle of an armed attack by Germany upon a small neighbour … will rouse the whole British Empire and compel the gravest decisions.

Do not, I pray be misled upon this point. Such a war, once started, would be fought out like the last, to the bitter end …

As I feel you should have some definite message to take back to your friends in Germany … I believe that a peaceful solution of the Czecho-slovak problem would pave the way for the true reunion of our countries on the basis of the greatness and the freedom of both.

In time to come, Churchill’s brief note would fall into the wrong hands, and become a death warrant for Ewald von Kleist-Schmenzin and many of his colleagues.

Three weeks after Kleist-Schmenzin’s visit to London, on Monday, 5 September, a young woman also checked in at Tempelhof ostensibly on a short visit to the British capital. Her luggage was light, but her mind bore a very important message. This was not the first text too secret to be written down which Susanne Simonis, the European correspondent for the Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, had memorised for her cousin Erich Kordt, the head of foreign minister Ribbentrop’s personal office – but it was the most important. For this was a piece of secret information to be passed to the very top of the British government by Kordt’s brother Theo, a senior diplomat at the German embassy in London – and it had the potential to avoid a world war. The message was that a high-level ‘conspiracy against Hitler exists in Germany and that a firm and unmistakable attitude by Britain and France would give the conspirators their opportunity [to remove the Führer] on the day that the German mobilization [for the invasion of Czechoslovakia] is announced’.

The day after Simonis’s arrival in London, Theo Kordt was smuggled into 10 Downing Street by the ‘secret’ door which leads from Horse Guards Parade into the prime minister’s garden. From there he was led up to the office of Chamberlain’s personal emissary to Hitler, Sir Horace Wilson. Wilson, who was also a convinced appeaser, listened attentively to Kordt’s message, and his assurance that if Britain and France stood up to Hitler on Czechoslovakia, the Wehrmacht would depose him at the instant he ordered the invasion. Wilson, who had met Kordt previously and trusted him, was impressed, and asked the German diplomat to return the following day to meet the foreign secretary, Halifax.

After listening to Kordt’s message the following evening, Halifax said he would do his best to ensure that the prime minister was informed – and perhaps some other cabinet colleagues too. Kordt was experienced enough to know that this was the kind of politeness the English use to cover lack of enthusiasm. He was shown back to the Downing Street garden door, and walked out onto Horse Guards Parade and into the London night puzzled and worried by Halifax’s muted response. And well he might have been. For Halifax could not tell his visitor that his master, Neville Chamberlain, had already decided not to resist Hitler’s demands for the Sudetenland, but to yield to them. ‘We could not be as candid with you as you were with us,’ Halifax was later to tell Kordt – long after the damage was done.

On Sunday, 11 September, four days after Kordt’s second backdoor visit to Downing Street, Vansittart’s secret emissary A.P. Young flew to Switzerland for another meeting with Carl Goerdeler in Zürich, once again at the German’s urgent request. The two met in the St Gotthard Hotel and strolled to Zürich’s Belvoir Park, where they spent two hours walking in the autumn sunshine among the flowerbeds and carefully manicured lawns, discussing the coming war and how it could now be stopped only by a combination of strong British and French action, backed by a coup to remove Hitler. At Zürich station that evening, as the world teetered towards the brink of war, Goerdeler waved goodbye to Young with the words, ‘Remember always that we shall win the last battle.’

7

‘All Our Lovely Plans’

In the early hours of Wednesday, 28 September 1938 an armed raiding party, nicknamed ‘Commando Heinz’ after its leader, gathered in the Hohenzollerndamm headquarters of the Wehrmacht’s Third Army Corps, responsible for the defence of Berlin. The unit consisted of fifty or sixty assorted desperadoes, ranging from Abwehr and Wehrmacht officers, to armed civilians and civil servants, to student leaders. Under the command of an ex-Nazi thug and serial revolutionary called Friedrich Wilhelm Heinz, they were ready for action and equipped with weapons supplied on the instructions of Admiral Canaris. ‘The silence of pre-dawn Berlin,’ a commentator wrote later, ‘was broken by the click-click-click of ammunition being loaded into [the magazines of] carbines and automatic weapons.’

Commando Heinz’s orders were to arrest Adolf Hitler at the moment he gave the order to invade Czechoslovakia at two o’clock that afternoon, and take him to a nearby hospital. There the dictator would be seen by the psychiatrist Dr Karl Bonhoeffer, the father of the great theologian, who would declare the Führer insane and commit him to a lunatic asylum. But some in the group did not intend to let Hitler get that far. They had secretly sworn to kill him in the confusion of the arrest.

The conspirators’ task was, on the face of it, not a difficult one. Only fifteen SS soldiers guarded Hitler in his Chancellery at any one time. The great double doors of the building would be secretly unlocked from the inside by one of the Foreign Office conspirators so as to give the raiding party easy access. There were plenty of reinforcements ready to come to the raiders’ assistance if required. In the Foreign Office and the Interior Ministry, anti-Nazi diplomats and officials had been issued with arms, and were ready to play their part. Other reserve forces made up of small groups of officers were waiting in private houses and apartments across the German capital, like the group holed up in the ornate white-stuccoed art-nouveau block of flats at Eisenacher Strasse 118, close to the government quarter. One of the plotters told his brother over dinner that evening, ‘Tonight Hitler will be arrested.’

There were good reasons for this confidence. Among those backing the putsch were the chief of the German staff and his predecessor, the commander-in-chief of the Wehrmacht, the political and operational leaders of the criminal police, the commander of the Berlin military district and one of his subordinates, the state secretary of the Foreign Office and his chief of ministerial office, the president of the Reichsbank, a senior official in the German embassy in London, another in the Department of Justice, and Hitler’s personal interpreter.*

The plot had been meticulously prepared.

Two weeks earlier, on 14 September, after several days spent carrying out a detailed reconnaissance of all the key sites, there was a full paper rehearsal of the coup plans, which incorporated the seizure of key Berlin police stations, an armed takeover of the state wireless transmitters, telephone installations and repeater stations, and the occupation of Hitler’s Chancellery and key ministries. When the exercise ended, General Erwin von Witzleben, the commander of the Berlin garrison and the coup’s de facto leader, declared that all preparations had been completed. They were ready. The moment Hitler gave the order to invade the Sudetenland, they would make their move.

But in all his careful preparations, Erwin von Witzleben had missed one crucial factor – the British prime minister.

On the evening of 14 September, as the coup rehearsal concluded in Berlin, Neville Chamberlain, in London, suddenly stunned everyone, including his own cabinet and Hitler (who was ‘flabbergasted’), by announcing that he would fly to the Führer’s mountain retreat at Berchtesgaden in the Bavarian Alps for talks the following day.

It is important at this point to record the precise sequence of events.

As a result of the messages from Goerdeler in early August and mid-September, and of the visit of Kleist-Schmenzin to London in mid-August, we can presume that the British government must have known of the existence of the plot against Hitler, although we cannot be certain that this knowledge extended to No. 10 and the prime minister. However, after Theo Kordt’s backdoor visit to No. 10 and his discussion with Halifax on the evening of 7 September, no such uncertainty is possible. From this moment onwards No. 10 knew of the plot, and it is overwhelmingly likely that the prime minister knew of it too. It is a matter of record that, at least from the end of August, Neville Chamberlain and his closest advisers had been secretly considering a personal last-minute appeal to Hitler. But the fact that this took place – stunning everyone, including the cabinet – just eight days after the Kordt visit raises the strong suspicion that the British prime minister’s sudden visit to Berchtesgaden was, if only in part, designed to pre-empt the coming coup so as to give Chamberlain the peacemaker his time upon the stage.

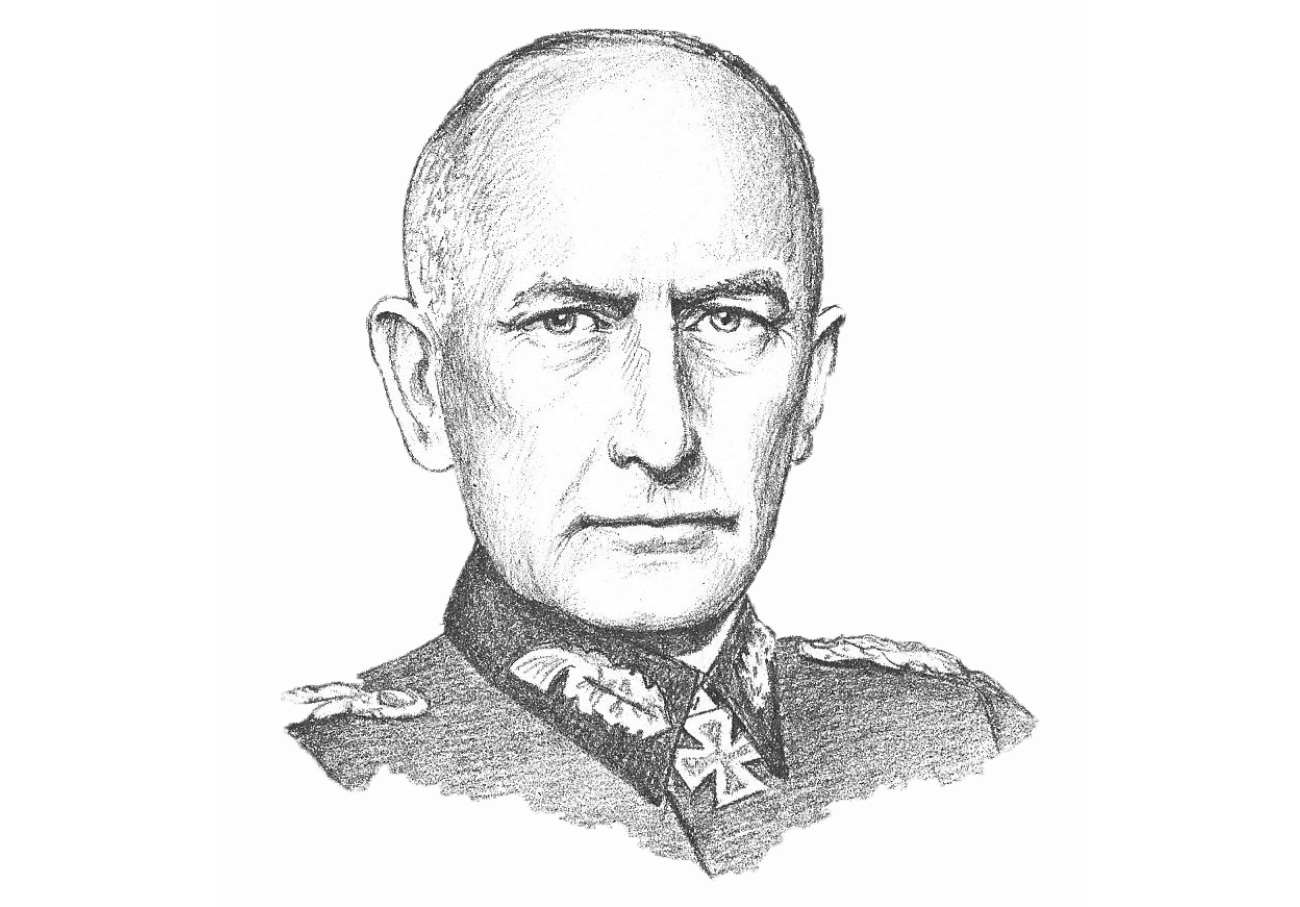

Erwin von Witzleben

Whatever the truth of this, Chamberlain’s unexpected flight in a specially chartered aircraft (it was his first time on a plane) to join Hitler at Berchtesgaden left the plotters crestfallen and discomfited. They had no option but to put their plans on ice and wait for developments.

In the talks that followed, Chamberlain privately conceded the Sudetenland to Hitler, subject to a plebiscite in the disputed territory and a number of other weak safeguards. Afterwards the British prime minister gave his impressions of the meeting and of Hitler in a letter to his sister, which concluded: ‘I thought I saw in his face … that here was a man who could be relied upon when he had given his word.’ Returning to London, Chamberlain met with the French and persuaded them to help pressure the Czechs into accepting the deal, despite the fact that it would effectively dismember their country. Eventually, the Czech president Edvard Beneš had no option but to cave in.

If Chamberlain expected a welcome from his cabinet on his return from Berchtesgaden, he did not get one. Their meeting of 17 September was fractious, and treated the prime minister’s ‘peace deal’ with deep scepticism. Even Halifax, Chamberlain’s right-hand man in the business of appeasement, expressed his opposition: ‘Hitler has given us nothing and is dictating terms as if he had won a war,’ he said. Duff Cooper, the First Lord of the Admiralty, was even blunter, warning the cabinet of the ‘danger of being accused of truckling to dictators and offending our best friends’. Britain should, he said, ‘make it plain that we would rather fight than agree to an abject surrender’.

But Chamberlain would not be diverted. Still determined to push through his peace plan, on 22 September he flew back to see Hitler at Bad Godesberg, near Bonn, expecting to sign the final agreement that would settle the Czech crisis.

He had another shock waiting for him. Instead of signing the deal, Hitler upped his demands with a new set of conditions for ‘peace’, accompanied by an ultimatum requiring the full and unconditional withdrawal of Czech forces from the Sudetenland by 1 October. Chamberlain was forced to fly home that evening crestfallen and empty-handed.

On 26 September the prime minister’s adviser Horace Wilson was despatched back to Berlin as Chamberlain’s ‘personal envoy’. His instructions were to deliver two messages. The first was the carrot: there should be a meeting between the Germans and the Czechs ‘with a view to settling by agreement the way in which the territory [of the Sudetenland] could be handed over’. The second, and more important, part of Wilson’s message was the stick: if Hitler rejected this course of action and invaded, then he should be clear that France’s treaty obligations to Czechoslovakia meant she would have to defend her ally with force, and Britain would join her.

Wilson met Hitler at 5 p.m. that day. The Führer, preparing for a big speech in the evening, was in a foul temper. As soon as he heard Chamberlain’s proposal for more talks he flew into a towering rage, shrieking that there would be no talks unless the Czechs first accepted his terms as outlined at Bad Godesberg. He followed this outburst by issuing another ultimatum – now he must have the Czechs’ answer by 2 p.m. on 28 September – just two days away.

The Führer abruptly terminated the meeting before Chamberlain’s envoy had the opportunity to deliver the crucial second part of the prime minister’s message, containing the threat of a British and French response in kind if Hitler chose the path of military action instead of talks.

The Berlin conspirators were delighted with this outcome. Now, at last, there was a precise date and time for the coup, and it was a mere two days away. ‘Finally we have clear proof that Hitler wants war, no matter what. Now [if he invades] there can be no going back,’ Hans Oster commented to a friend. The carefully laid plans to remove Adolf Hitler were reinstated, and the key coup plotters began moving into position.

On the morning of the next day, 27 September, there were the first signs of a stronger British line: the Royal Navy was ordered to move to battle stations. Hitler, taken aback, said to Göring, ‘The English fleet might shoot after all.’

At midday Wilson, at Chamberlain’s insistence, returned to see the Führer, this time finally giving the strong warning that the prime minister had asked him to deliver the previous day: if Hitler attacked, France would act and Britain would follow.

According to insiders in Berlin, Hitler had already started to wobble. At 9 a.m. Carl Goerdeler sent an urgent telegram to Vansittart: ‘Don’t give away another foot. Hitler is in a most uncomfortable position …’

But then the rollercoaster lurched again.

Whatever ‘tough’ message was meant by the mobilisation of the British fleet and the warning Wilson delivered to Hitler, what the British prime minister said in his now infamous BBC broadcast to the nation at 6.15 that evening could not have been read by the German leader as anything other than a signal that Britain would not act if Czechoslovakia was invaded:

How horrible, fantastic, incredible it is that we should be digging trenches and trying on gas-masks here because of a quarrel in a far-away country between people of whom we know nothing. It seems still more impossible that a quarrel that has already been settled in principle should be the subject of war … However much we may sympathise with a small nation confronted by a big and powerful neighbour, we cannot in all circumstances undertake to involve the whole British Empire in war simply on her account. If we have to fight it must be on larger issues than that.

All eyes now focused on Hitler’s deadline – 2 p.m. the following day. The coup plotters and their forces were on hairtrigger alert, and the world held its breath.

The morning hours of 28 September ticked past in much scurrying to and fro between the various groups of plotters in their secret locations across Berlin. Von Witzleben calmed one of his colleagues who tried to persuade him to launch early: ‘It won’t be long now.’ At 11 a.m. Erich Kordt got a call from his brother Theo at the German embassy in London informing him, on apparently good information, that Britain would indeed declare war if Hitler launched his armies at 2 p.m.

What Theo Kordt did not know, however, was that an hour earlier, at 10 a.m., Chamberlain had rung the British ambassador in Rome and instructed him to get a message to Mussolini asking the Italian dictator to intervene ‘in the last useful hours to save peace and civilization’. The ambassador swiftly passed the message on to Il Duce. At 11 a.m., as Erich Kordt was being assured that Britain was ready to go to war at two o’clock that afternoon, Mussolini, who had been something of a bystander up to now, was ringing the Italian ambassador in Berlin, Bernardo Attolico: ‘Go to the Führer and tell him, considering that I will be by his side, whatever may happen, that I advise him to delay the start of hostilities for twenty-four hours. In the meantime I intend to study what can be done to resolve the problem.’

Shortly afterwards a second message from No. 10 arrived at the British embassy in Rome instructing the ambassador to get a message to the Italians ‘suggesting Mussolini supports Chamberlain’s proposal for a conference in Germany involving Italy, Germany, France and Britain to solve the Sudetenland problem’. A little later a telegram arrived in Downing Street from the ambassador in Rome saying that Mussolini had agreed to Chamberlain’s proposal, and would recommend it to Hitler.

As all this was going on, a constant stream of visitors flowed in and out of Hitler’s Chancellery. At 11.15 the French ambassador, the luxuriantly moustachioed André François-Poncet, speaking on behalf of both Paris and London and unaware of what had been happening between London and Rome, urged Hitler to accept Chamberlain’s proposal for more talks. Twenty-five minutes later a portly, stooped figure emerged from a taxi. Bald, bespectacled, sweating, breathless and without his hat, ambassador Attolico scurried in through the Chancellery doors, bearing the message from Mussolini. Hitler broke off from seeing François-Poncet to meet the new arrival. ‘Il Duce informs you,’ Attolico said, his high-pitched voice rising several notes from the tension, ‘that whatever you decide, Führer, Fascist Italy stands behind you. Il Duce is, however of the opinion that it would be wise to accept the British proposal and begs you to refrain from mobilisation.’ Finally, with just two hours to go to the 2 p.m. deadline, Hitler, the man whose reputation had been built on ‘the triumph of the will’, backed down, announcing that, instead of invading Czechoslovakia, he would accept talks at Munich.