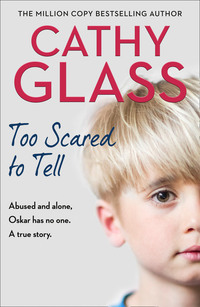

Too Scared to Tell

‘Who are they?’ I asked, puzzled.

He shrugged.

‘Are they your sisters?’

He shook his head.

‘Cousins? Friends?’

He shrugged again and began to look very worried, so I didn’t pursue it. Perhaps he was just confused by all the changes, but I’d have to tell his social worker. He would be checking Oskar’s home and seeing the sleeping arrangements for himself before he returned Oskar to his mother’s care.

‘We’ve got a nice big garden,’ I said, drawing him to the window. His room was at the rear of the house and overlooked the garden. He was just tall enough to see over the windowsill. ‘You can play out there when the weather is nice, and we also have a park nearby.’

Oskar turned from the window to survey the room. ‘Do you like your bedroom?’ I asked. He didn’t reply. ‘Once we have some of your belongings from home in here it will feel more comfortable.’ Still no response. ‘Would you like to see the rest of the upstairs?’

He gave a small nod.

He slipped his hand into mine again and I showed him the toilet first, and at the same time asked him if he needed to use it, but he didn’t. ‘This is Adrian’s room,’ I said, moving to the next door along the landing. ‘He’s grown up now, but you’ll meet him later when he gets in from work.’ I opened Adrian’s bedroom door just so Oskar could see inside. ‘All our bedrooms are private,’ I said. ‘Just for us.’ I closed Adrian’s door and went along the landing, opening and closing the girls’ bedroom doors, the bathroom and finally my bedroom.

‘There is where I sleep,’ I said.

He looked in. ‘Do I sleep in here?’

‘No, love, in your own bedroom, the one we went in first. If you need me in the night, just call out and I’ll come to you.’

He looked puzzled and then asked, ‘Do you sleep by yourself?’

‘Yes. I’m divorced. Do you know what that means?’

He nodded. ‘Mummy is.’

‘OK. Come on, let’s find something to do,’ I said, and closed my bedroom door.

‘Shall I go to bed?’ he asked.

‘It’s a bit early yet. Come downstairs with me and you can play, then we’ll have dinner, and later you can go to bed.’

Oskar did as I asked, and once we were downstairs he came with me into the kitchen-diner where Paula was laying the table ready for dinner later. ‘Thanks, love,’ I said to her.

‘I need to get on with some college work now,’ she said.

‘Yes, you go. Thanks for your help.’

‘I’ll see you at dinner,’ she told Oskar and, with a smile, left.

The casserole was cooking in the oven and wouldn’t be ready for half an hour, so I suggested to Oskar that we go into the living room and play with some toys. He came with me, obedient and compliant but not enthusiastic. We sat on the floor by the toy boxes and I began taking out some of the toys, games and puzzles, trying to capture his interest. He watched me but didn’t join in. I wasn’t wholly surprised. It might take days, if not weeks, before he relaxed enough to play. Children vary.

‘Do you understand why you are in care and staying with me for now?’ I asked him. Although his social worker would have explained this and I had talked to Oskar about it in the car, there was so much to take in that, when stressed and anxious, it’s easy to forget.

He didn’t reply, so I said, ‘I’m a foster carer and I live here with my family. We are going to look after you, as your mummy can’t at present.’

I would have expected a child of his age to understand the concept phrased this way. Miss Jordan, his teacher, had said Oskar had a good grasp of English and his learning was above average. But Oskar looked at me blankly and then asked, ‘Does Mummy look after me?’

‘Yes, I think so. Usually.’ That was the impression I’d been given and what his social worker and teacher believed. But Oskar was looking bewildered, and given we knew so little about him, I thought I should try to clarify this. ‘Did your mummy look after you before she went away?’ I asked.

‘Looked after?’ he repeated questioningly.

‘Yes, made your meals, washed your clothes, played with you.’

‘No. Maybe. Sometimes,’ he said, confused.

‘Who else looked after you?’ I asked.

He shrugged. ‘I don’t know all their names.’

‘The uncles who took you to school?’

‘Sometimes.’

The set-up at Oskar’s home seemed even more complex than his social worker or school had realized. Most children who come into care have a bond with and are loyal to their main care-giver, usually a parent or relative, even if they’ve been neglected or abused. They often try to portray them in a more positive light than they deserve out of loyalty, but not so with Oskar. He seemed to be struggling with the idea of being looked after at all.

‘When Mummy is at home, does she make your meals and spend time with you?’ I asked lightly, picking up a toy and approaching the matter from a different angle.

‘She works,’ he said, watching me.

‘OK, but when she doesn’t work, is she the one who takes care of you?’

He shrugged and began to look anxious, so again I let the subject drop. Once he was feeling more at ease, hopefully he’d begin to talk.

‘Don’t worry,’ I said. ‘Let’s go and see how the casserole is doing.’ I offered him my hand and we went into the kitchen, where Oskar waited a safe distance from the hot oven as I opened the door and gave the casserole a stir.

‘Hmm, that smells nice,’ he said.

‘Good. Another fifteen minutes and it will be ready to eat. What would you like to drink with your meal?’

‘Water, please.’

I poured a tumbler of water and set it at his place on the table. We tend to keep the same places at the meal table, as many families do. I showed Oskar his place. I was expecting Adrian and Lucy to arrive home at any moment and I’d just begun telling him a little bit about them when I heard Lucy let herself in the front door. ‘Hi, Mum!’ she shouted, making Oskar start.

‘Quietly, Lucy,’ I called. She bounced into the kitchen.

‘Hi, Oskar,’ she cried, delighted to see him. She was a qualified nursery assistant and I knew that sometimes she’d been asked to quell her exuberance at work, but I was pleased she was so outgoing and happy. It had been very different when she’d first come to me as a foster child, withdrawn and with an eating disorder. (I tell Lucy’s story in Will You Love Me?) She’d done amazingly well and was now a permanent member of my family. I’d adopted her and loved her as much as I did my birth children – Adrian and Paula.

Having said a few words to Oskar, Lucy went upstairs to change out of her work clothes. Five minutes later Adrian arrived home, making a slightly more reserved entrance. He came in, said hello to Oskar, kissed my cheek, asked if I’d had a good day and then went upstairs to change. I gave him and Lucy a few minutes and then called everyone to dinner. I dished up and we settled around the table to eat.

I always anticipate that our new arrival may feel uncomfortable for the first few days, surrounded by new people and customs, especially at the meal table when we are all in close proximity and the noise level rises as we talk about our day. Lucy entertained us with a funny story about a child at nursery, and Adrian said a little about his day at work as a trainee accountant. Paula talked of her day at college, and I of fostering and the part-time clerical work I did mainly from home.

As we chatted and ate, I watched Oskar but he didn’t seem to mind all the talking or being surrounded by new people. He ate well and had seconds, and a pudding. It was later, after dinner, when I began his bedtime routine, that his anxiety set in again. I’d read him a story in the living room and at seven o’clock I said it was time for bed.

‘Do I have to sleep upstairs?’ he asked.

‘Yes, love, that’s where the beds are.’

‘Can I sleep on the floor downstairs?’

‘No, that would be very uncomfortable,’ I said. ‘Do you sleep in a bed at your home?’ I’d fostered children before who’d had to sleep on the sofa or a mattress on the floor because there wasn’t money for a bed.

He didn’t reply but came with me to the bathroom, where I’d set out a fresh towel, toothbrush, soap, sponge, clean pyjamas and so forth from my spares.

‘I don’t want a bath,’ he said as soon as we went in.

‘Would you like a shower instead?’ I asked.

‘No.’ He began to look worried again.

‘OK, just have a good wash tonight. I expect you’re tired. You can have a bath tomorrow.’ I never usually insist a child has a bath or shower on their first night; I wait until they feel more comfortable with me.

I ran water for him in the washbasin and then waited while he washed his face, going carefully over his cheek where the bruise was. ‘That looks sore,’ I said.

He shrugged. I thought Miss Jordan had done well to get Oskar talking about how he got the mark on his face, as he was saying so little to me. But she’d had a term – four months – to gain his trust, while I’d only had a few hours. I hoped in time he’d start to trust me and open up. He washed his hands and brushed his teeth, then I handed him his pyjamas.

‘Do you need help changing into your pyjamas or shall I wait outside?’ I asked him, respecting his privacy.

‘I want to sleep in my clothes,’ he said, immediately growing anxious. ‘Please let me sleep in my clothes.’ His eyes filled.

An icy chill ran up my spine. I hoped I was wrong, but a child not wanting to undress can be a sign that they’ve been sexually abused.

Chapter Three

Protecting Oskar

Preoccupied with Oskar’s reaction to changing into his night clothes, I picked up his pyjamas and we went round the landing to his bedroom. I certainly wouldn’t be forcing him to change, but I hoped to be able to persuade him, and also to find out the reason for his reluctance to undress. There might be a perfectly innocent explanation, although as a very experienced foster carer I had my doubts.

It was still light outside and I asked Oskar if he liked to sleep with his curtains closed, open or open a little. On their first night I always ask a child this and other questions regarding how they like their bedroom. It’s small details like this that help them settle in a strange room. He replied, ‘I think they’re closed.’

‘OK.’

‘Do you like to sleep with your bedroom light on or off? Or I can dim it a little if you wish.’ I thought if I made his room as he was used to then he’d start to feel more secure.

He didn’t reply so I showed him what I meant by switching the light on and off and then dimming it. ‘On or off?’ I asked again. ‘Or dimmed?’

‘It goes on and off a lot,’ he said. ‘It wakes me up.’

‘You mean the light flashes?’ I asked, slightly baffled. I wondered if he lived in a built-up area where car headlights caught his bedroom window, or possibly a neon shop sign flashed on and off late at night.

‘They keep switching it on,’ Oskar said.

‘Who do?’ I asked.

‘The people in the house.’

‘Oh. What people are they, love?’

He clammed up again. So often in fostering the child is reluctant to confide to begin with and foster carers (and social workers) have to become detectives, gently easing the information from them. We also have to be receptive if a child starts to tell us something, as what they are really trying to say may not be obvious.

‘This room is your bedroom and only you sleep here,’ I emphasized, hoping to make him feel safe. ‘I won’t come into your room and switch on the light unless you want me to. You can have your door open or closed, just as you wish. When it is time to get up for school, I will knock on your door to wake you and then you can call out, “Come in.”’

‘Knock on my door,’ he repeated, as though he hadn’t a clue what I was talking about.

‘Yes, like this.’ I stepped outside, drew the door to, knocked on it and said, ‘It’s Cathy, can I come in? Then you say, “Yes, come in.”’

I demonstrated again and on the second try he called out, ‘Yes, come in.’

‘Great,’ I said. ‘Well done. Remember, it’s your room. You’re in charge of it. OK?’

He nodded, and at that point I think he began to accept that he was going to be safe, for his face lost some of its unease and he started looking around the room. There wasn’t really much to see without his possessions: furniture, posters on the walls, and I’d put in a toy box and some soft toys. Now he was more relaxed I thought I’d ask him to change. I really needed him to change into night clothes so I could wash his school uniform, and I didn’t want him to start a habit of sleeping every night in his day clothes.

‘Oskar, I’m going to wait outside while you change into your pyjamas and get into bed. Then, once you are ready, you can call out “come in”.’ Without waiting for a refusal, I stepped outside the door, drew it to and waited. A few minutes later his little voice rang out. ‘I’m in bed. You can come in.’ I smiled.

Even so, I knocked on the door before I went in. ‘Well done,’ I said, and scooped up his day clothes. ‘I’ll wash these ready for school tomorrow.’

‘Will you take me to school?’ he asked, his little face peeping over the duvet.

‘Yes, and collect you. Now I want you to try to get some sleep. You’ve had a very tiring day. Would you like a goodnight kiss?’ I always check, otherwise it can be an uncomfortable invasion of the child’s personal space and terrifying for those who have been abused.

Oskar shook his head and looked worried. ‘It’s fine, you don’t have to have a kiss. I’ll just say goodnight and see you in the morning. Call out if you need me.’ I tucked him in and went to the door. ‘Would you like your door left open, closed or a little open?’ I asked him again.

‘Closed,’ he said.

‘OK.’

Leaving the light on low, I came out convinced there was far more going on for Oskar than anyone knew.

Downstairs, I put his clothes in the washer-dryer and then checked his school’s website for its start and finish times. After that, I set about writing up my log notes while I had the chance. All foster carers in the UK are required to keep a daily record of the child or children they are looking after. This includes appointments, the child’s health and well-being, education, significant events and any disclosures the child may make about their past. As well as charting the child’s progress, it can act as an aide-mémoire. When the child leaves, this record is placed on file at the social services. Some carers type these, but I’m not alone in preferring to keep a written record and then emailing a résumé as part of my monthly report to the child’s social worker and my supervising social worker.

As I wrote, I included collecting Oskar from school, that he’d eaten a good meal, how he appeared to be coping with being in care and his comments where appropriate. The account has to be objective, so I didn’t include that I thought there was far more going on in Oskar’s life than anyone knew about. This was conjecture at present and time would tell if I was right or not. Once I’d completed my notes for the day, I stored the folder in a locked drawer in the front room with other important paperwork.

I went upstairs and quietly checked on Oskar. He was fast asleep. I then spent some time talking to Adrian, Paula and Lucy, who thought Oskar was a lovely boy but looked very troubled – ‘as though he has the weight of the world on his shoulders’, Paula said. This wasn’t altogether surprising considering he’d just come into care, regardless of whatever else might have happened in his past. I said I hoped that in time he would start to relax and look a bit happier, as other children we’d fostered had. Generally, children have amazing resilience and adapt to change – in my opinion, they are all little heroes.

Aware that Oskar would probably have an unsettled first night, I went to bed shortly after ten o’clock. I never sleep well when there is a new child in the house. I’m half listening out in case they wake frightened, not knowing where they are and in need of reassurance. I checked on Oskar around 2.00 a.m., and when I woke at 6.00 he was still asleep. Indeed, he slept through until 7.00, when I gently woke him to get ready for school.

‘Where am I?’ he asked, sitting bolt upright in bed.

‘You’re staying with me, Cathy,’ I said quietly.

‘Oh yes, I remember.’ He rubbed his eyes.

I now expected him to ask me when he would see his mummy, as most children would. He’d hardly mentioned her the evening before and he didn’t now. He simply got out of bed, used the toilet, and then I left him to change into his school uniform that I’d laundered the night before. I’d buy another school uniform today, as we couldn’t get by on one and I didn’t know if or when his clothes would be sent from home. Sometimes parents send their child’s belongings once they are less upset and angry about their child going into care, others don’t, in which case I replace the lot.

I waited on the landing while Oskar dressed and then took him downstairs for breakfast, talking to him and reassuring him. Although he wasn’t saying much, he still looked anxious. Adrian and Lucy were already at the table having their breakfasts and said hi to Oskar. He looked at them warily. Paula didn’t have to leave as early as they did and would come down shortly. On a weekday my family usually fix their own breakfasts and then at the weekend, when there is more time, I often make a cooked breakfast.

At dinner the evening before, Oskar had sat next to Adrian where I’d laid his place, but this morning he seemed to purposely go around him to the other side of the table. He sat next to Lucy, as far away from Adrian as possible. ‘I’m honoured,’ Lucy said with a smile, having also noticed Oskar’s decision. It was where Paula usually sat at the table, but she wouldn’t mind.

‘What would you like for breakfast?’ I asked Oskar. ‘Cereal, toast, yoghurt, fruit?’

He looked confused. ‘Would you like to come and see what we have?’ I suggested.

‘You can choose what you want,’ Lucy prompted when he didn’t move.

‘Within reason,’ I added. I wasn’t about to let him have a chocolate bar and fizzy drink for breakfast, as some children I’d fostered were used to. Foster carers are expected to provide healthy, nutritious meals for their family and the children they look after.

Oskar slid quietly from his chair and came into the kitchen, where I opened the cupboard doors and the fridge to show him the choices. He didn’t seem to spot anything he might like. I opened the bread bin. ‘Or toast?’ I asked him.

‘I have rolls, a bit like those,’ he said, pointing, clearly used to something different.

I took out the bag of wholemeal rolls. ‘Would you like these for now and then after school we can go to the supermarket and you can show me what you like to eat?’

He nodded.

‘How many rolls?’

‘One,’ he said.

‘What would you like in it?’

I showed him what we had and he chose ham and a slice of cheese as a filling, and a drink of orange juice. By the time he sat down at the table to eat, Adrian and Lucy were leaving to get ready for work. I took my coffee and sat with Oskar as he ate. It wasn’t long before the smell of ham brought Sammy in, nose twitching. I gave him a stroke and then kept an eye on him, making sure he didn’t jump up and steal some ham, as he tried to do sometimes.

‘Do you like the cat?’ Oskar asked me as he ate.

‘Yes.’ I smiled. ‘He’s like one of the family. Do you have a pet?’

‘At my house …’ he began, and stopped.

‘Yes, love?’

But he continued eating, clearly having decided not to say any more on that topic. Then he asked, ‘Can we go to school now?’

‘When you’ve finished your breakfast. There’s no rush.’

Paula appeared and said hi to us both before getting herself some breakfast. She sat next to me and we talked a little about her college as Oskar finished his roll and then drank the juice.

‘Can we go to school now?’ he asked again the moment he’d finished.

‘Yes, but there’s plenty of time. We won’t be late.’ Given that he’d often been late for school in the past, I guessed it was worrying him.

‘Have a good day,’ Paula said as Oskar and I left the table.

‘And you, love,’ I replied.

I took Oskar upstairs to wash his face and hands and brush his teeth, and then downstairs again we put on our jackets and shoes. He appeared to be very self-sufficient and didn’t need much help from me.

‘Are we going to school now?’ he asked as we got into the car.

‘Yes, but don’t worry, you won’t be late.’

He asked me again as I drove and I said, ‘We’re going to school, but it’s a different route to the one you’re used to, as I live in a different part of town.’

‘I like school,’ he said.

‘Good, I’m pleased.’

‘I like school,’ he said again a minute later. ‘I wish I could stay there.’

I glanced at him in the rear-view mirror. He was looking out of his side window, frowning, deep in thought as he often seemed to be.

‘Why do you prefer school to home?’ I asked gently. Many children like school, but preferring it to home was unusual and also worrying. I’d had children before disclose abuse while I’d been driving. I think it helps, not being able to see the person’s face when saying something painful, similar to writing it down or confiding in a diary.

Oskar hadn’t replied, but he was still frowning and continued to gaze out of his side window.

‘Why is school better than your home?’ I asked again lightly, keeping my eyes on the road ahead. ‘Can you think of a reason?’

‘My teacher is nice,’ he offered.

‘Yes. She is nice,’ I agreed. Although that alone wouldn’t normally be enough for a child to prefer school to home.

‘Are the people in your house nice?’ I asked.

He didn’t reply, but as I looked again in the rear-view mirror I saw him imperceptibly shake his head and his frown deepen.

‘Oskar, love, is there anything about your home life that is worrying you and you can tell me? I know you were able to tell Miss Jordan some things yesterday and that was very brave of you. Is there anything else you want to say?’ He didn’t reply. ‘If you do think of anything, you know you can tell me or Miss Jordan. We are both here to help you.’

But he changed the subject. ‘There’s a cat like Sammy,’ he said, pointing through the window.

‘Yes, he is,’ I agreed.

I parked outside Oskar’s school and he couldn’t get out of the car fast enough, his face losing some of its angst. As soon as we entered the playground, Miss Jordan appeared. I think she must have been looking out for us. She came straight over.

‘My teacher!’ Oskar cried, delighted.

‘How are you, Oskar?’ she asked emotionally. I know teachers aren’t supposed to encourage physical contact with their pupils, but she allowed him a hug.

‘He’s doing fine,’ I told her. ‘He had a good night’s sleep and is eating well.’

‘That’s a relief. I had a sleepless night worrying about him.’ I knew how she felt! ‘I’m sure he’s looking better already, less tired,’ she said. I had thought so too – the dark rings under his eyes were fading. ‘Can you come into reception?’ she asked me. ‘The secretary needs you to fill in a form with your contact details. There wasn’t time yesterday.’

‘Yes. I also need to buy Oskar another school uniform,’ I said.

‘You might not have to. Oskar’s uncle, Mr Nowak, has just brought in a big bag of Oskar’s belongings.’

‘Really? That was quick.’ I was surprised, but pleased Oskar was going to be reunited with some of his possessions.