The History of Gambling in England

The History of Gambling in England

INTRODUCTORY

Difference between Gaming and Gambling – Universality and Antiquity of Gambling – Isis and Osiris – Games and Dice of the Egyptians – China and India – The Jews – Among the Greeks and Romans – Among Mahometans – Early Dicing – Dicing in England in the 13th and 14th Centuries – In the 17th Century – Celebrated Gamblers – Bourchier – Swiss Anecdote – Dicing in the 18th Century.

Gaming is derived from the Saxon word Gamen, meaning joy, pleasure, sports, or gaming– and is so interpreted by Bailey, in his Dictionary of 1736; whilst Johnson gives Gamble —to play extravagantly for money, and this distinction is to be borne in mind in the perusal of this book; although the older term was in use until the invention of the later – as we see in Cotton’s Compleat Gamester (1674), in which he gives the following excellent definition of the word: – “Gaming is an enchanting witchery, gotten between Idleness and Avarice: an itching disease, that makes some scratch the head, whilst others, as if they were bitten by a Tarantula, are laughing themselves to death; or, lastly, it is a paralytical distemper, which, seizing the arm, the man cannot chuse but shake his elbow. It hath this ill property above all other Vices, that it renders a man incapable of prosecuting any serious action, and makes him always unsatisfied with his own condition; he is either lifted up to the top of mad joy with success, or plung’d to the bottom of despair by misfortune, always in extreams, always in a storm; this minute the Gamester’s countenance is so serene and calm, that one would think nothing could disturb it, and the next minute, so stormy and tempestuous that it threatens destruction to itself and others; and, as he is transported with joy when he wins, so, losing, is he tost upon the billows of a high swelling passion, till he hath lost sight, both of sense and reason.”

Gambling, as distinguished from Gaming, or playing, I take to mean an indulgence in those games, or exercises, in which chance assumes a more important character; and my object is to draw attention to the fact, that the money motive increases, as chance predominates over skill. It is taken up as a quicker road to wealth than by pursuing honest industry, and everyone engaged in it, be it dabbling on the Stock Exchange, Betting on Horse Racing, or otherwise, hopes to win, for it is clear that if he knew he should lose, no fool would embark in it. The direct appropriation of other people’s property to one’s own use, is, undoubtedly, the more simple, but it has the disadvantage of being both vulgar and dangerous; so we either appropriate our neighbour’s goods, or he does ours, by gambling with him, for it is certain that if one gains, the other loses. The winner is not reverenced, and the loser is not pitied. But it is a disease that is most contagious, and if a man is known to have made a lucky coup, say, on the Stock Exchange, hundreds rush in to follow his example, as they would were a successful gold field discovered – the warning of those that perish by the way is unheeded.

Of the universality of gambling there is no doubt, and it seems to be inherent in human nature. We can understand its being introduced from one nation to another – but, unless it developed naturally, how can we account for aboriginals, like the natives of New England, who had never had intercourse with foreign folk, but whom Governor Winslow1 describes as being advanced gamblers. “It happened that two of their men fell out, as they were in game (for they use gaming as much as anywhere; and will play away all, even the skin from their backs; yea, and for their wives’ skins also, although they may be many miles distant from them, as myself have seen), and, growing to great heat, the one killed the other.”2

The antiquity of gambling is incontestable, and can be authentically proved, both by Egyptian paintings, and by finding the materials in tombs of undoubted genuineness; and it is even attributed to the gods themselves, as we read in Plutarch’s Ἰσιδος και Ὀσιριδος “Now the story of Isis and Osiris, its most insignificant and superfluous parts omitted, is thus briefly narrated: – Rhea, they say, having accompanied with Saturn by stealth, was discovered by the Sun, who, hereupon, denounced a curse upon her, that she should not be delivered in any month or year. Mercury, however, being likewise in love with the same goddess, in recompense for the favours which he had received from her, plays at tables with the Moon, and wins from her the seventieth part of each of her illuminations; these several parts, making, in the whole, five new days, he afterwards joined together, and added to the three hundred and sixty, of which the year formerly consisted: which days are even yet called by the Egyptians, the Epact, or Superadded, and observed by them as the birth days of their Gods.”

But to descend from the sublimity of mythology to prosaic fact, we know that the Egyptians played at the game of Tau, or Game of Robbers, afterwards the Ludus Latrunculorum of the Romans, at that of Hab em hau, or The Game of the Bowl, and at Senat, or Draughts. Of this latter game we have ocular demonstration in the upper Egyptian gallery of the British Museum, where, in a case containing the throne, &c., of Queen Hatasu (b. c. 1600) are her draught board, and twenty pieces, ten of light-coloured wood, nine of dark wood, and one of ivory – all having a lion’s head. These were all, probably, games of skill; but in the same case is an ivory Astragal, the earliest known form of dice, which could have been of no use except for gambling. The Astragal, which is familiarly known to us as a “knuckle bone,” or “huckle bone,” is still used by anatomists, as the name of a bone in the hind leg of cloven footed animals which articulates with the tibia, and helps to form the ankle joint. The bones used in gambling were, generally, those of sheep; but the Astragals of the antelope were much prized on account of their superior elegance. They also had regular dice, numbered like ours, which have been found at Thebes and elsewhere; and, although there are none in our national museum, there are some in that of Berlin; but these are not considered to be of great antiquity. The Egyptians also played at the game of Atep, which is exactly like the favourite Italian game of Mora, or guessing at the number of fingers extended. Over a picture of two Egyptians playing at this gambling game is written, “Let it be said”: or, as we might say, “Guess,” or “How Many?” Sometimes they played the game back to back, and then a third person had to act as referee.

The Chinese and Indian games of skill, such as Chess, are of great antiquity; but, perhaps, the oldest game is that of Enclosing, called Wei-ki in Chinese, and Go in Japanese. It is said to have been invented by the Emperor Yao, 2300 b. c., but the earliest record of the game is in 300 b. c. It is a game like Krieg spiel, a game of war. There are not only typical representatives of the various arms, but the armies themselves, some 200 men on each side; they form encampments, and furnish them with defences; and they slay, not merely a single man, as in other games, but, frequently, hosts of men. There is no record of its being a gambling game, but the modern Chinese is an inveterate gambler.

As far as we know, the ancient Jews did not gamble except by drawing, or casting lots; and as we find no word against it in the inspired writings, and, as even one of the apostles was chosen by lot (Acts i. 26), it must be assumed that this form of gambling meets with the Divine approval. We are not told how the lots were drawn; but the casting of lots pre-supposes the use of dice, and this seems to have been practised from very early times, for we find in Lev. xvi. 8, that “Aaron shall cast lots upon the two goats; one lot for the Lord, and the other lot for the scape goat.” And the promised land was expressly and divinely ordained to be divided by an appeal to chance. Num. xxvi. 52 and 55, 56, “And the Lord spake unto Moses, saying… Notwithstanding the land shall be divided by lot: according to the names of the tribes of their fathers they shall inherit. According to the lot shall the possession thereof be divided between many and few.” The reader can find very many more references to the use of the “lot” in any Concordance of the Bible. But in their later days, as at the present time, the Jews did gamble, as Disney3 tells us when writing on Gaming amongst the Jews.

“Though they had no written law for it, Gamesters were excluded from the Magistracy, incapable of being chosen into the greater or lesser Sanhedrim; nor could they be admitted as Witnesses in any Court of Justice, till they were perfectly reformed. Some of their reasons for excluding such from the Magistracy were, that their gaming gave sufficient presumption of their Avarice, and, besides, was an employment no way conducing to the public good: a covetous man, and one who is not wise and public spirited, being very unfit for offices of so much trust and power, as well as dignity. The presumption of Avarice was the cause, also (and a very good one), of not admitting the evidence of such a man. And that other notion they had, that the gain arising from play was a sort of Rapine, is as just a ground for the Infamy which stained his character, and subjected him to these incapacities.

“This last consideration, that money won by gaming was looked upon as got by Theft, makes it reasonable to conclude that such money was to be restored, and that the winning gamester was punished as for Theft: which was not, by their law, a capital crime; but answered for, in smaller cases (and, probably, in this, among the rest), by double Restitution: Exod. xxii. 9.

“But the partiality of that people is evident, in extending the notion of Theft, only to Gaming amongst themselves; i. e., native Jews and proselytes of righteousness; for, if a Jew played, and won of a Gentile, it was no Theft in him: but it was forbidden to him on another account, as Gaming is an application of mind entirely useless to human society. For, say the Talmudists, ‘Tho’ he that games with a Gentile does not offend against the prohibition of Theft, he violates that de rebus inanibus non incumbendo: it does not become a man, at any time of his life, to make anything his business which does not relate to the study of wisdom or the public good.’ Now, as this was only a prohibition of their doctors, perhaps the law, or usage in such cases might take place, that the offender was to be scourged.”

Among the Greeks and Romans the first gambling implement was the ἀστραγαλος, or (Lat.) Talus, before spoken of. In the course of time the sides were numbered, and, afterwards, they were made of ivory, onyx, &c., specimens of which may be seen in the Etruscan Saloon of the British Museum, Case N. In the Terra Cotta room is a charming group of two girls playing with Astragals, and in the Third Vase room, on Stand I., is a vase, or drinking vessel, in the shape of an Astragal (E. 804). Subsequently the Tessera, or cubical die, similar to that now used, came into vogue (samples of which may be seen in Case N. in the Etruscan Saloon), and they were made of ivory, bone, porcelain, and stone. Loaded dice have been found in Pompeii. They also had other games among the Romans, such as Par et Impar (odd or even), in which almonds, beans, or anything else, were held in the hand, and guessed at – and the modern Italian game of Mora was also in vogue.

But gambling was looked down upon in Rome, and the term aleator, or gambler, was one of reproach – and many were the edicts against it: utterly useless, of course, but it was allowed during the Saturnalia. Money lost at play could not be legally recovered by the winner, and money paid by the loser might by him be recovered from the person who had won and received the same.

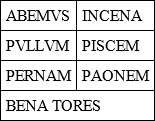

The excavations at Pompeii and other places in modern times have revealed things not known in writings; and, treating of the subject of gambling, we are much indebted to Sig. Rodolfo Lanciani, Professor of Archæology in the University of Rome. Among other things, he tells us how, in the spring of 1876, during the construction of the Via Volturno, near the Prætorian Camp, a Roman tavern was discovered, containing besides many hundred amphoræ, the “sign” of the establishment engraved on a marble slab.

The meaning of this sign is double: it tells the customers that a good supper was always ready within, and that the gaming tables were always open to gamblers. The sign, in fact, is a tabula lusoria in itself, as shown by the characteristic arrangement of the thirty-six letters in three lines, and six groups of six letters each. Orthography has been freely sacrificed to this arrangement (abemus standing for habemus, cena for cenam). The last word of the fourth line shows that the men who patronised the establishment were the Venatores immunes, a special troop of Prætorians, into whose custody the vivarium of wild beasts and the amphitheatrum castrense were given.

He also tells us that so intense was the love of the Roman for games of hazard, that wherever he had excavated the pavement of a portico, of a basilica, of a bath, or any flat surface accessible to the public, he always found gaming tables engraved or scratched on the marble or stone slabs for the amusement of idle men, always ready to cheat each other out of their money.

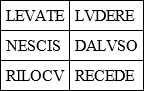

The evidence of this fact is to be found in the Forum, in the Basilica Julia, in the corridors of the Coliseum, on the steps of the temple of Venus at Rome, in the square of the front of the portico of the Twelve Gods, and even in the House of the Vestals, after its secularisation in 393. Gaming tables are especially abundant in barracks, such as those of the seventh battalion of vigiles, near by St Critogono, and of the police at Ostia and Porto, and of the Roman encampment near Guise, in the Department of the Aisne. Sometimes when the camp was moved from place to place, or else from Italy to the frontiers of the empire, the men would not hesitate to carry the heavy tables with their luggage. Two, of pure Roman make, have been discovered at Rusicade, in Numidia, and at Ain-Kebira, in Mauritania. Naturally enough they could not be wanting in the Prætorian camp and in the taverns patronised by its turbulent garrison, where the time was spent in revelling and gambling, and in riots ending in fights and bloodshed. To these scenes of violence the wording of the tables often refers; such as

“Get up! You know nothing about the game; make room for better players!” Two paintings were discovered, in Nov. 1876, in a tavern at Pompeii, in one of which are seen two players seated on stools opposite each other, and holding on their knees the gaming table, upon which are arranged, in various lines, several latrunculi4 of various colours, yellow, black and white. The man on the left shakes a yellow dice box, and exclaims, “Exsi” (I am out). The other points to the dice, and says, “Non tria, duas est” (Not three points, but two). In the next picture the same individuals have sprung to their feet, and show fight. The younger says, “Not two, but three; I have the game!” Whereupon, the other man, after flinging at him the grossest insult, repeats his assertion, “Ego fui.” The altercation ends with the appearance of the tavernkeeper, who pushes both men into the street, and exclaims, “Itis foris rix satis” (Go out of my shop if you want to fight).

During Sig. Lanciani’s lifetime, a hundred, or more, tables have been found in Rome, and they belong to six different games of hazard; in some of them the mere chance of dice-throwing was coupled with a certain amount of skill in moving the men. Their outline is always the same: there are three horizontal lines at an equal distance, each line containing twelve signs – thirty-six in all. The signs vary in almost every table; there are circles, squares, vertical bars, leaves, letters, monograms, crosses, crescents and immodest symbols: the majority of these tables (sixty-five) contain words arranged so as to make a full sentence with the thirty-six letters. These sentences speak of the fortune, and good, or bad, luck of the game, of the skill and pluck of the players, of the favour, or hostility, of bystanders and betting men. Sometimes they invite you to try the seduction of gambling, sometimes they warn of the risks incurred.

Children were initiated into the seductions of gambling by playing “nuts,” a pastime cherished also by elder people. In the spring of 1878 a life-size statuette of a boy playing at nuts was discovered in the cemetery of the Agro Verano, near St Lorenzo fuori le mura. The statuette, cut in Pentelic marble, represents the young gambler leaning forward, as if he had thrown, or was about to throw, the nut; and his countenance shows anxiety and uncertainty as to the success of his trial.

The game could be played in several ways. One, still popular among Italian boys, was to make a pyramidal “castle” with four nuts, three at the base and one on the top, and then to try and knock it down with the fifth nut thrown from a certain distance. Another way was to design a triangle on the floor with chalk, subdividing it into several compartments by means of lines parallel to the base; the winnings were regulated according to the compartment in which the nut fell and remained. Italian boys are still very fond of this game, which they call Campana, because the figure drawn on the floor is in the shape of a bell: it is played with coppers. There was a third game at nuts, in which the players placed their stakes in a vase with a large opening. The one who succeeded first in throwing his missile inside the jar would gain its contents.

They also tossed “head or tail,” betting on which side a piece of money, thrown up in the air, would come down. The Greeks used for this game a shell, black on one side, white on the other, and called it “Night or day.” The Romans used a copper “as” with the head of Janus on one side, and the prow of a galley on the other, and they called their game Capita aut navim (head or ship).

Mahomet discountenanced gambling, as we find in the Koran (Sale’s translation, Lon. 1734), p. 25. “They will ask thee concerning wine and lots. Answer: In both there is great sin, and also some things of use unto men; but their sinfulness is greater than their use.” Sale has explanatory footnotes. He says “Lots. The original word, al Meiser, properly signifies a particular game performed with arrows, and much in use with the pagan Arabs. But by Lots we are here to understand all games whatsoever, which are subject to chance or hazard, as dice, cards, &c.” And, again, on p. 94. “O true believers, surely wine, and lots, and images, and divining arrows are an abomination of the work of Satan; therefore avoid them, that ye may prosper.”

À propos of this denunciation of gambling in the Koran, is the following highly interesting letter of Emmanuel Deutsch, in the Athenæum of Sep. 28, 1867: —

“It may interest the writer of the note on κυβεια (Eph. iv. 14), (the only word for ‘gambling’ used in the Bible) in your recent ‘Weekly Gossip,’ to learn that this word was in very common use among Paul’s kith and kin for ‘cube,’ ‘dice,’ ‘dicery,’ and occurs frequently in the Talmud and Midrash. As Aristotle couples a dice player (κυβευτης) with a ‘bath robber’ (λωποδυτης), and with a ‘thief’ (ληστης – a word no less frequently used in the Talmud); so the Mishnah declares unfit either as judge or witness ‘a κυβεια-player, a usurer, a pigeon-flyer (betting man), a vender of illegal (seventh year) produce, and a slave.’ A mitigating clause – proposed by one of the weightiest legal authorities, to the effect that the gambler and his kin should only be disqualified ‘if they have but that one profession’ – is distinctly negatived by the majority, and the rule remains absolute. The classical word for the gambler, or dice player, appears aramaized in the same sources into something like kubiustis, as the following curious instances may show. When the Angel, after having wrestled with Jacob all night, asks him to let him go, ‘for the dawn hath risen,’ Jacob is made to reply to him, ‘Art thou a thief, or a kubiustis, that thou art afraid of the day?’ To which the Angel replies, ‘No, I am not; but it is my turn to-day, and for the first time, to sing the Angelic Hymn of Praise in Heaven: let me go.’”

In another Talmudical passage, an early Biblical critic is discussing certain arithmetical difficulties in the Pentateuch. Thus, he finds the number of the Levites (in Numbers) to differ, when summed up from the single items, from that given in the total. Worse than that, he finds that all the gold and silver contributed to the sanctuary is not accounted for; and, clinching his argument, he cries, “Is then your Master, Moses, a thief or a kubiustis?” The critic is then informed of a certain difference between “sacred” and other coins, and he further gets a lesson in the matter of Levites and First-born, which silences him. Again, the Talmud decides that if a man have bought a slave who turns out to be a thief or a kubiustis– which has been erroneously explained to mean a “man-stealer” – he has no redress. He must keep him, as he bought him, or send him away, for he bought him with all his vices.

No wonder dice-playing was tantamount to a crime in those declining days. There was, notwithstanding the severe laws against it, hardly a more common and more ruinous pastime – a pastime in which Cicero himself, who places a gambler on a par with an adulterer, did not disdain to indulge in his old days, claiming it as a privilege of “Age.” Augustus was a passionate dice-player. Nero played the points – for they also played it by points – at 400,000 sesterces. Caligula, after a long spell of ill-luck, in which he had lost all his money, rushed into the streets, had two innocent Roman knights seized, and ordered their goods to be confiscated. Whereupon he returned to his game, remarking that this had been the luckiest throw he had had for a long time. Claudius had his carriages arranged for dicing convenience, and wrote a work on the subject. Nor was it all fair play with those ancients. Aristotle already knows of a way by which the dice can be made to fall as the player wishes them; and even the cunningly constructed, turret-shaped dice cup did not prevent occasional “mendings” of luck. The Berlin Museum contains one “charged” die, and another with a double four. The great affection for this game is seen, among other things, by the common proverbs taken from it, and the no less than sixty-four names given to the different throws, taken from kings, heroes, gods, hetairæ, animals, and the rest. But the word was also used in a mathematical sense. In a cosmogonical discussion of the Midrash, the earth is likened to a “cubus.”

The use of dice in England is of great antiquity, dating from the advent of the Saxons and the Danes and Romans; indeed, all the northern nations were passionately addicted to gambling. Tacitus (de Moribus Germ.) tells us that the ancient Germans would not only hazard all their wealth, but even stake their liberty upon the throw of the dice; “and he who loses submits to servitude, though younger and stronger than his antagonist, and patiently permits himself to be bound, and sold in the market; and this madness they dignify by the name of honour.”

In early English times we get occasional glimpses of gambling with dice. Ordericus Vitalis (1075-1143) tells us that “the clergymen and bishops are fond of dice-playing” – and John of Salisbury (1110-1182) calls it “the damnable art of dice-playing.” In 1190 a curious edict was promulgated, which shows how generally gambling prevailed even among the lower classes at that period. This edict was established for the regulation of the Christian army under the command of Richard the First of England and Philip of France during the Crusade. It prohibits any person in the army, beneath the degree of knight, from playing at any sort of game for money: knights and clergymen might play for money, but none of them were permitted to lose more than twenty shillings in one whole day and night, under a penalty of one hundred shillings, to be paid to the archbishops in the army. The two monarchs had the privilege of playing for what they pleased, but their attendants were restricted to the sum of twenty shillings, and, if they exceeded, they were to be whipped naked through the army for three days. The decrees established by the Council held at Worcester in the twenty-fourth year of Henry III. prohibited the clergy from playing at dice or chess, but neither the one nor the other of these games are mentioned in the succeeding statutes before the twelfth year of Richard II., when diceing is particularised and expressly forbidden.