Ground Truth: 3 Para Return to Afghanistan

GROUND TRUTH

3 Para: Return to Afghanistan

PATRICK BISHOP

To Douglas and Richenda

Contents

List of Illustrations

Maps

Introduction: A Big Ask

1 Going Back

2 Through the Looking Glass

3 KAF

4 Hearts and Minds

5 Hunting the Hobbit

6 Green Zone

7 IED

8 The Stadium

9 Facing the Dragon

10 Sangin Revisited

11 The White Cliffs of Helmand

12 Convoy

13 The Enemy

14 Close Quarters

15 Fields of Fire

16 ‘Something our Parents will Understand’

17 Homecoming

Abbreviations, Acronyms and Military Terms

Acknowledgments

By the Same Author

Index

Copyright

About the Publisher

The following account is based on interviews with the soldiers of 16 Air Assault Brigade. The author has made his best endeavour to report events accurately and truthfully and any insult or injury to any of the parties described or quoted herein or to their families is unintentional. The publishers will be happy to correct any inaccuracies in later editions.

Some names have been changed or omitted to protect operational security.

List of Illustrations

Brigadier Mark Carleton-Smith © Sergeant Anthony Boocock, 16 Air Assault Brigade photographer/Crown Copyright

Major Stuart McDonald © Tina Hager

Sangin schoolroom © Patrick Bishop

A Para leads women to safety © Jason P. Howe/ConflictPics

‘A’ Company patrols a poppy field © Captain Ian McLeish

Paras patrolling in Hutal © Tina Hager

Colour Sergeant Mark Kennedy with children in Qal-e-Gaz

© Captain Ian McLeish

‘A’ Company at a Maywand Base © Marco di Lauro/Getty Images

Paras navigating Maywand ditches © Jason P. Howe/ConflictPics

6 Platoon, ‘B’ Company patrol outside Hutal © Tina Hager

‘Gungy Third’ aboard a Chinook to Inkerman © Patrick Bishop

FOB Inkerman sangar sentry © Patrick Bishop

Privates Ben Biddulph and Andy Shawcross at Inkerman © Patrick Bishop

End of patrol at FOB Inkerman © Patrick Bishop

Sergeant Major Stu Bell © Patrick Bishop

Captain Ben Harrop © Patrick Bishop

Paras tabbing along a Mizan route © Christopher Pledger

Sergeant Chris Prosser at Inkerman © Patrick Bishop

Paras run to board a Chinook © Christopher Pledger

‘A’ Company prepare to assault © Captain Ian McLeish

Tabbing back to base in Zabul © Sergeant Ian Harding, 16 Air Assault Brigade Photographer/Crown Copyright

‘B’ Company patrol in Mizan © Christopher Pledger

Corporal Marc Stott © Patrick Bishop

Lieutenant Fraser Smith in Band-e-Timor © Patrick Bishop

Arrival at Kadahar Stadium © Marco di Lauro/Getty Images

Lance Corporal Andy Lanaghan with an ANA soldier

Paras patrol Kandahar City © Sergeant Craig Allen, Parachute Regiment Photographer/Crown Copyright

Bathing in the Sangin irrigation channel © Patrick Bishop

Sangin civilian © Patrick Bishop

Taking a breather in the Sangin Green Zone © Patrick Bishop

Corporal Mike French © Patrick Bishop

Corporal Bev Cornell © Corporal Bev Baljit Kaur Cornell

Corporal Marianne Hay with her dog Deanna © Patrick Bishop

HET tractor and trailer rig © Patrick Bishop

Satellite image of Kajaki dam by kind permission of Regional Command South

Major Stuart McDonald and Brigadier Huw Williams in Kajaki Sofia © Sergeant Anthony Boocock, 16 Air Assault Brigade photographer/Crown Copyright

Kajaki District Leader Abdul Razzak announces the ceasefire is off© Patrick Bishop

Major John Boyd © Patrick Bishop

A 500-pound bomb at Kajaki Sofia © Patrick Bishop

Corporal Stu Hale © Patrick Bishop

Flying the 3 Para flag © Christopher Pledger

Endpapers

‘A’ Company regroup after an air assault in Maywand © Jason P. Howe/ConflictPics

While every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright material reproduced herein, the publishers would like to apologise for any omissions and would be pleased to incorporate missing acknowledgments in future editions.

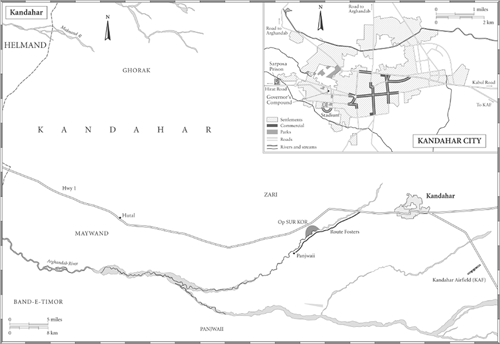

List of Maps

1 Regional Command South xv 2 Upper Sangin Valley xvi-xvii 3 Kandahar xviii-xix 4 Maywand xx-xxi 5 Kajaki xxii 6 Upper Gereshk Valley xxiii

Introduction: A Big Ask

When 3 Para arrived back in Colchester in the autumn of 2008 after their second tour of Afghanistan in three years, their commanding officer, Huw Williams, pointed out the difference between his generation of soldiers and the very young men he was leading.

‘When I joined the army we thought we would have to go Northern Ireland and might possibly have to go somewhere else to fight,’ he said. ‘But these guys knew when they joined that they would be expected to go off, more or less straight away, to a full-on war.’

A British soldier’s job today is much more difficult and dangerous than it was in the last decades of the twentieth century. Then it was easily possible to go through an entire career without hearing a shot fired in anger. Now, a new recruit to a combat unit is virtually certain to see action. Thanks to Afghanistan, before long almost everyone will have a war story to tell. Since the British Army went there in force in 2006, about 40,000 servicemen and women have come and gone. That represents more than a third of the country’s ground troops. Some of them have now been twice. Force levels are rising steadily. There is no end in sight to the conflict and no obvious short cut that would allow an early but honourable exit. A spell in ‘Afghan’, as the soldiers call it, is becoming as routine as an Ulster roulement was thirty years ago.

There are some similarities. The skills and drills honed on the terraced streets of Belfast and Londonderry and the fields of Fermanagh and Tyrone have proved surprisingly useful in the river valleys of Helmand.

The differences, though, are far bigger. Ulster was grim, but Afghanistan is harrowing. The violence is deeper, darker and more disturbing. There were no suicide bombers in Northern Ireland. Life in Afghanistan’s front-line forts is harsh, squalid, exhausting and dangerous. Soldiers know that once they step through the gates they are facing six months of knackering patrols, regular fire-fights and the constant nerve-fraying fear that the next step they take may trigger a buried bomb.

They are operating in an extreme climate in wild country among people whose culture, try as the soldiers might to understand it, remains baffling and opaque. There’s nothing in the recent memory of the British Army to draw on for help. You have to go back more than a hundred years to match the experience. Any soldier reading Winston Churchill’s account of his time with the Malakand Field Force fighting Pathan (Pashtun) tribesmen in the North West Frontier in 1897 would feel a buzz of recognition at his tales of Tommies and their native allies battling with heat, thirst, slippery local leaders and opponents steeped in a culture of violence.

‘The strong aboriginal propensity to kill, inherent in all human beings, has… been preserved in unexampled strength and vigour,’ he wrote. ‘That religion, which above all others was founded and propagated by the sword — the tenets and principles of which are instinct with incentives to slaughter and which in three continents has produced fighting breeds of men — stimulates a wild and merciless fanaticism.’*

The strain of a tour is enormous, reflected in the number of soldiers diagnosed with mental disorders.* But the burden also lies heavy on the folk they leave behind. For those with families, Afghan duty means being absent from hearth and home not just for the six months of the deployment but also for lengthy pre-operational training exercises. By the end of 2010, some members of 3 Para will have done three Afghan stints in five years.

It is, as the soldiers say, ‘a big ask’. It is not as if they are going to fight in a popular cause. British public opinion remains resolutely sceptical about the value of the campaign. Most people seem unwilling to accept the government’s assertion that by fighting in Afghanistan we are defending the home front against a threat as great as that posed by the Nazis. The scepticism shows no sign of eroding. Progress, military and political, is deemed to be non-existent or far too slow to merit the cost in blood, money and effort.

At the same time, the public are full of admiration for the soldiers. The standing of the services in civilian eyes is probably higher than at any time since the Second World War. It is not difficult to see why. Their culture of stoicism and comradeship are points of light in a world of blighted materialism and egocentricity They remind us, perhaps, of the way we like to think we once were.

The soldiers are pleased to be appreciated. But they, who pay the price of Britain’s policy, do not share the civilians’ pessimism. From what I have seen and heard, there is no significant reluctance to serve in Afghanistan and if necessary to do so again and again. ‘Are we prepared to do it?’ asked 3 Para’s former regimental sergeant major John Hardy. ‘Yes we are. Every time.’ The soldiers are driven back by a number of impulses. One is professional satisfaction. Almost every soldier in a volunteer army welcomes the prospect of action. Another is their sense of duty which has stood up well to the climate of self-interest prevalent in civilian life.

But there is more to it than that. Soldiers have a refreshingly clear-cut sense of right and wrong. They sympathise with the Afghan people, caught between the cruelty of the insurgents and the venality of the authorities, and want to help them. The job is tough and dangerous and brimming with frustrations and disillusionment, but the prizes of safety at home and a better Afghanistan are considered, if they can be won, to be worth it. The soldiers’ enthusiasm, though, is finite. A military stalemate will eventually lower morale and degrade performance. If there are no signs that the Afghan government is serious about governing, that process will accelerate.

The phrase ‘ground truth’ is a military expression, meaning how things are compared with how they are imagined to be. Soldiers know the ground truth better than anyone; yet, it seems to me, their voices have not been given the attention they deserve. They have some extraordinary tales to tell. This book reveals some of their stories as well as their thoughts, fears and anxieties about a conflict that, for good or for bad, is shaping both them and us.

* Winston S. Churchill, The Story of the Malakand Field Force: An Episode of Frontier War, Project Gutenberg, E-Book #9404.

* In 2007, according to the Ministry of Defence, 375 Armed Forces personnel who had previously served in Afghanistan were assessed as having a mental disorder.

1 Going Back

He had imagined this moment often during the last two years. Now, after an hour-long climb along a rocky, sun-baked ridge line, it had arrived. Corporal Stuart Hale shielded his eyes from the mid-morning glare and looked down at the corrugated hillside. The slope was the colour of khaki, bare apart from a scattering of rocks. It was just like a thousand others that undulated across Helmand. There was nothing to show that it was here that his life, and the lives of several of his comrades, had been swept so traumatically off course.

His mates left him alone to enjoy the satisfaction of having made it up unaided. It was cool up here after the baking heat of the valley, quiet too, the silence disturbed only by the occasional boom of mortars in Kajaki camp and the rustling noise the bombs made as they flew past.

Eventually he spoke. ‘I was up there when I spotted them,’ he said, pointing to a crag above. ‘They looked like Taliban, and they seemed to be setting up a checkpoint to stop people on the road down there.’ That morning, 6 September 2006, he had grabbed his rifle and bounded down the hill to get a better look. When he reached a dried-up stream bed he hopped across without thinking. ‘Normally I jump with a two-footed landing’ cause that’s how you’re supposed to do it. A good paratrooper lands feet and knees together. But this time I got a bit lazy and just jumped with one foot.’ The lapse was a stroke of luck. It meant that only his right foot was blown off when he landed on the mine. The detonation was the start of a long ordeal for him and the men who went to his rescue. Four more soldiers were injured and two lost limbs. Corporal Mark Wright was killed.

Hale was rescued after hours of muddle and delay. Back in hospital in Britain he was plunged into a new trauma. Recovering from surgery, he suffered vivid paranoid hallucinations. He believed the doctors were plotting to kill him and that his girlfriend was so horrified by his injuries that she was frozen with fear on the other side of the ward door, unable to face him.

Eventually the nightmares passed. Hale did everything the doctors and physiotherapists asked, determined to regain as much as he could of the fitness he had been so proud of. Now, two years later, he was standing on the peaks above Kajaki, a welcome breeze drying the sweat on his face, after climbing 300 metres up a goat track on one real leg and one artificial one.

In the summer of 2006, Stuart Hale was a private soldier, serving as a sniper in Support Company of the Third Battalion of the Parachute Regiment. 3 Para had formed the core of the battle-group tasked with bringing stability to the province of Helmand, which until then had been virtually ignored by the international force occupying Afghanistan. Helmand was a peripheral province, a pitifully backward corner of a very poor country. No one knew precisely what would happen when British troops got there. Certainly no one anticipated the storm of violence that blew up after the Paras’ arrival. From June onwards, all over the province, the soldiers were pitched into exhausting battles with bands of Taliban who fought with suicidal ferocity to drive them out.

The British were soon stretched to snapping point. They found themselves stranded in remote outposts, dependent almost entirely on helicopters to get food and ammunition in and to take casualties out. At times it seemed they might be overrun. But, showing a bravery and determination that have hardened into legend, they clung on. Their courage was reflected in the medals that followed, a haul that included a VC, awarded to Corporal Bryan Budd, who died winning it. Another thirteen men from the battlegroup were killed. Forty more were seriously wounded.

Now the Paras were back. Since they had bid a thankful farewell to Helmand in the autumn of 2006, three more British expeditionary forces had arrived, fought for six months, and gone home. In that time another fifty-four soldiers had been killed and scores more seriously wounded. The arrival of 16 Air Assault Brigade in the spring of 2008 put more troops than ever on the ground. They lived in fortresses planted near the main settlements and the rough roads that joined them together. They were squalid places, unsanitary, cramped and uncomfortable. But despite their gimcrack construction they looked as if they were going to be there for a long time.

There was no end in sight to Britain’s Afghan adventure. Even the politicians who had launched the deployment into southern Afghanistan in a cloud of optimism admitted that. In the summer of 2006 the 3 Para Battlegroup had won virtually every encounter they had fought and killed many insurgents. No one knew an exact number but a figure of up to a thousand was mentioned. These were heavy losses for a small guerrilla force, living off the land and among the people. The beatings had forced them to change their tactics of reckless, head-on attacks. But they seemed as determined as ever to keep on fighting. As long as they did so there was little chance that progress would be made with the activity that the government said was the real point of the British deployment. The soldiers were there to make Helmand a better place, by building roads and schools and hospitals, but more importantly by creating an atmosphere free of fear within which Afghans could begin to take charge of their lives.

Looking down from the ridge line towards Route 611, the potholed, rocky track that links the mud villages strung along the Sangin Valley, it seemed to Stuart Hale that morning that, if anything, things had gone backwards since he was last there.

On the day he was wounded, he had decided to descend from the OP and engage the Taliban himself with his sniper rifle, rather than calling in a mortar strike on them. ‘I didn’t want there to be any risk of collateral damage because there were women shopping, kids playing,’ he said. ‘The place was really thriving.’ Now he looked down at the silent compounds, the empty road and the deserted fields. ‘No one wants to live here any more,’ he said sadly. ‘It’s a ghost town.’

The area is called Kajaki Olya. It lies a few kilometres from the Kajaki dam, a giant earthwork that holds back the Helmand river. British troops had been sent to Kajaki in June 2006 to help protect it from attacks by the Taliban. The insurgents saw it as an important prize. Its capture would be a propaganda triumph that would also give them control of the most important piece of infrastructure in the region. The chances of them succeeding were tiny. In the regular squalls of violence that swept Kajaki it was the civilians who suffered most. The number of innocents killed so far in this Afghan war is not known, but it is many more than the combined total of the combatant dead. Soon, living close to Kajaki became too dangerous, even for the farming families whose customary blithe fatalism always impresses Westerners.

But now it seemed that life was about to get better, not only for the people around Kajaki but in towns and villages all over southern Afghanistan. We were waiting for the start of a big operation, the high point of the British Army’s 2008 summer deployment. If it succeeded it would give much-needed support to the claims of the foreign soldiers that they were in Afghanistan to build and not to destroy. 16 Air Assault Brigade was about to attempt to realise a project that had been under consideration for two years. It had been postponed several times on the grounds that it was too dangerous, and probably physically impossible. The plan was to deliver the components for a turbine which, when installed in the dam’s powerhouse, would light up Helmand and carry electricity down to Kandahar to turn the wheels of a hundred new projects. It involved carting the parts on a huge convoy across desert and mountain and through densely planted areas of the ‘Green Zone’ where the Taliban would be lying in wait. The Paras, together with a host of other British and Afghan soldiers, were now gathering in the last days of August, to protect the convoy as it reached Route 611 and the last and most dangerous phase of its epic journey.

Now, as we toiled along the ridgeway that switchbacked up and down the three peaks dominating Kajaki, we could hear the sounds of fighting drifting up from the Green Zone. Our destination was Sparrowhawk West, on top of the most southerly crag. Stu Hale led the way in. The OP gave an eagle’s-eye view of the whole valley, from the desert to the east to the green strip of cultivation, watered by the canals that run off the Helmand river, across to the wall of mountains that rears up on the far bank. A team of watchers has sat there night and day, winter and summer, since the spring of 2006. The operation to clear the way had already begun. Down at the foot of the hill we could see sleeping bags spread out like giant chrysalises in a compound at the side of the 611, which 3 Para’s ‘A’ Company had taken over the night before.

Through the oversized binoculars mounted in the sangars we watched a patrol moving southwards along the road. They were from 2 Para, which manned the Kajaki camp, pushing down towards a line of bunkers known as ‘Flagstaff and Vantage’—the Taliban’s first line of defence. A thin burst of fire drifted up from the valley. ‘That’s coming from Vantage,’ said one of the observers. It was answered immediately by the bass throb of a heavy machine gun, followed by a swishing noise, like the sound of waves lapping the seashore, as .50-cal bullets flowed through the air. 2 Para’s Patrols Platoon, lying up on the high ground overlooking the road to provide protection, were shooting back.

The firing died away. For a while, peace returned to the valley. On the far side of the river there were people in the fields. The bright blue burkas of the women stood out from the grey-green foliage like patches of wild flowers. Then, noiselessly, there was an eruption of white smoke at the foot of the hill, followed by a flat bang. ‘Mortar,’ said someone, and the binoculars turned to the west. We strained our eyes towards a stretch of broken ground on the far side of the river, scattered with patches of dried-up crops and dotted with abandoned-looking compounds. Somewhere in the middle appeared a spurt of flame and a puff of smoke. This time the mortar appeared to be heading in our direction. We ducked into a dugout and it exploded harmlessly a couple of hundred metres away. The Taliban had given themselves away. The trajectory was picked up on a radar scanner and the firing point pinpointed, a compound just under a kilometre off. Then we heard a noise like a giant door slamming coming from the battery of 105mm guns on the far side of the Kajaki dam and the slither of the shells spinning above our heads. There was a brief silence followed by a flash and a deep, dull bang, and a pillar of white smoke stained with pulverised earth climbed out of the fields.