Inner City Pressure

But something was pulling hard in the opposite musical direction – to the dark side. On this side of UK garage’s personality split, mostly male MCs dominated instead of crooning singers; the instrumentals conjured not a glitzy VIP area but a low-lit council estate. It was inner London’s millennial aspiration and promise versus the grim reality that persisted when those aspirations failed to materialise. Darker garage that was built around breakbeats and accompanied by jungle’s hectic lyrical energy was thriving on pirate radio, while the more established, soulful tracks dominated the charts and high-street clubs. When catchy, sample-heavy novelty records like DeeKline’s ‘I Don’t Smoke’ started to take off in the garage clubs, and the likes of Heartless Crew, So Solid Crew and Pay As U Go Cartel started to have hits themselves, the divisions deepened. For the old guard, there was a ‘last days of disco’ feel to the new millennium: the resplendent purity of one of the greatest periods in British music history having to come to terms with its own looming mortality – these were the best days of our lives, and this is how it ends? With some hyperactive teenagers chatting about guns and drug dealing, instead of a smooth, 2-step shuffle and some sweetly sung love songs? With a song that samples the Casualty theme tune and a Guy Ritchie film? No wonder they were upset.

Bizarrely, the tensions between the old guard and the new wave came to a head in the unlikely context of the UK garage committee meetings. It sounds somehow reminiscent of the kind of sit-down familiar from The Sopranos, where representatives of the mafia families would thrash out their differences, negotiate and cut deals. A similar thing had happened in the jungle scene too, when prominent figures had attempted – in some cases, successfully – to blacklist General Levy’s raucous party-starting anthem ‘Incredible’, after he had claimed to be ‘runnin’ jungle’. The substance of the tension at the turn of the millennium was that the new guard were sullying garage’s grown-up reputation, both musically and in terms of the rebellious gangster pose they sometimes presented to the world; they didn’t like the chat about gats and violence, and they didn’t like the exuberant use of novelty samples either. The straw that broke the camel’s back was Oxide and Neutrino’s ‘Bound 4 Da Reload’ going to number one in May 2000, and ‘I Don’t Smoke’ following it in to number 11, after months as an underground smash. Prominent gatekeeper DJs like Norris ‘Da Boss’ Windross and Radio 1’s The Dreem Team refused to play either record. ‘I don’t like many of those records of that style,’ DJ Spoony from the Dreem Team told the Guardian at the time. ‘I like music with more soul and groove in it.’ When So Solid Crew appeared on their Radio 1 show that winter, the atmosphere was frosty to say the least: ‘Give the youth of nowadays a chance to bust through that barrier,’ Romeo told them, ‘cos you lot have been there for so long, and it’s our time now.’

In the meetings, there was some discussion of whether the darker, ‘breakbeat’ garage would also attract more undesirable elements to the clubs. ‘I was always bearing the brunt of it,’ recalls Maxwell D. ‘“Who’s this crew, Pay As U Go, talking all this gangster stuff? We don’t want them in the dances, they’re thugs, they’re this, they’re that …” They really didn’t want to give us the mic.’ (Unfortunately for him, Maxwell found himself on the sharp end of exactly this kind of condescension and obstruction again, years later, when he made a light-hearted funky house tune about his mobile phone called ‘Blackberry Hype’ – the kids loved it, the grown-ups, less so.)

For Matt Mason, editor of RWD magazine from 2000–05, who also DJed on garage station Freek FM, the combative, transitional period was exciting, even if the end result was inevitable: ‘There was a real sense the new guys were doing something different, that a chasm was opening up in garage. It’s interesting because it really crept up. First there was just some really weird records, I think from about 1999. There was the Groove Chronicles tunes first, like okay, that’s different, and some MJ Cole records, like … all right, some different thoughts have gone into this. And then there was a record by Dem 2, under the alias US Alliance, called “All I Know”, and “Da Grunge” remix of it was this fucking mutated thing, that had mutated out of garage, and I remember hearing it at Twice as Nice and just thinking, “What the fuck is that? That’s not garage.”

‘At first I really didn’t want to see garage splinter, because I liked that you could play a weird breakbeat record into a Todd Edwards record, into an old school, Strictly Rhythm house record, into a DJ Zinc record at 148bpm, I felt this was such a good thing, don’t let it break into a thousand pieces and die. But obviously it did, and that was great too.’ Mason attended the UK garage committee meetings, which were hosted and coordinated by the old guard, with Norris Windross as chairman, Spoony as spokesman, and well-established DJs such as Matt Jam Lamont and MCs such as Creed on one side; positioned against them, the likes of Mason, Maxwell D, producer Jaimeson and MC Viper:

‘We went along because we wanted to give the new generation a voice,’ Mason tells me over Skype from his home in California. ‘I really liked all the guys on the other side, but at the time I butted heads with them, especially Matt Jam; I remember him having a go at us for putting a grime artist on the cover of RWD – it was one of the MCs from Hype Squad, this young crew who were on Raw Mission FM. This was still only 2001, it was a kid sitting on a bike and he was making gunfingers. And they all said, “You’re promoting violence, you shouldn’t be promoting these artists, this isn’t garage,” and I said, “Well, look: they’re playing it in garage stations and garage clubs, and they’re buying the records in garage shops, from the garage section. And I think you’re right, I think maybe this isn’t garage, and it’s becoming something else – but, we absolutely should be fucking covering it, of course it’s going to be on our front cover.”’

Oxide and Neutrino, as members of So Solid Crew and also a very successful duo in their own right, responded to the ire sent their way for their scrappy, cheeky ‘Bound 4 Da Reload’ tune with an appropriately punk follow-up, called ‘Up Middle Finger’, describing the garage scene’s jealous whining about their success, and bans in clubs and radio stations on playing their songs. ‘All they do is talk about we, something about we’re novelty, cheesy … did I mention we’re only 18?’ They had sold 250,000 copies of ‘Bound 4 Da Reload’, and ‘Up Middle Finger’ became their third Top 10 hit in a row. That record scratch was the sound of the old guard being rewound into the history books. ‘Garage didn’t really want us involved in their scene,’ as Lethal Bizzle said years later, ‘so we started making our own thing.’

That’s not to say there wasn’t some fluidity between the two camps, or some overlap in taste and affection from the kids for the old guard: just that in that intense moment, the Oedipal urge to shrug off your elders and gatekeepers requires a bit of front, if you’re going to claim the stage. Even within Pay As U Go – really the critical proto-grime crew, in terms of its personnel – there was a slight difference in aesthetics. You can see it in the video to ‘Champagne Dance’, Pay As U Go’s one proper chart single, where Wiley and the rest of the crew are dressed in tracksuits, and Maxwell D, who, following a tough upbringing, wasn’t about to let the opportunity to dress like a star pass him by:

‘I had money from the street from selling drugs, and then I went straight into music, and was living like a drug dealer, legally. That’s why I stood out a lot in the crew. That’s why when people saw me they were like, “Rah he’s dressed in all these name brand, expensive clothes.” Even in my music videos I’d say to the stylist woman, “Look, I want a fur jacket yeah? I don’t want to wear what I wear in the street.” The rest of the crew were all like, “Why are you wearing a fur jacket?” and I’m like, “Because it’s a music video! I’m going to go all out, I’m going to make myself look like a pimp.” That was the garage style thing: dress to impress.’

During their brief time in the limelight signed to Sony, Pay As U Go were given the major-label rigmarole to promote ‘Champagne Dance’. Wiley was given the surprisingly high-profile job of remixing Ludacris’s ‘Roll Off’; they appeared on CBBC with Reggie Yates, and on Channel 4’s Faking It programme, advising the lawyer-turned-UK-garage-MC George on how to be less of a ‘Bounty’ (black on the outside, white on the inside), and get a bit of street cool. The most unlikely of these promotional activities was a tour of school assemblies around London and beyond, in Birmingham and Reading too; Flow Dan and Maxwell D took the helm, and the other MCs, including Wiley and Dizzee, would join them too. On one occasion, the disjunction between urban stars in the hood and a pop-friendly, public-facing crew reached a nadir. ‘Sony made them go out on a schools tour,’ Ross Allen told Emma Warren. ‘I was like, “Nick [Denton, their manager], how’s the tour going?” He was like, “I just had Wiley on the phone and they’re well fucked off,” and I was like, “Why?” They’d been sent to this school and they were playing to five-year-olds – they’re on the mic and these little kids are doing forward rolls in front of them.’12

There was a baton being passed, and in spite of the £100,000 advance the crew received from Sony, and ‘Champagne Dance’ reaching number 13, Maxwell D was in a minority with his inclination for a fur coat. ‘I wouldn’t ever have said, “Take that Nokia!”’ Maxwell reflects, referencing the Dizzee lyric, as emblematic of the new generation’s hunger, ‘because I could already buy five Nokias if I wanted – it wouldn’t have made sense. But Dizzee, he’d just come off the street, he had that mentality.’ And of course, if you’re a 15-year-old, especially a poor 15-year-old, there’s no financial barrier to becoming an MC – you’ve seen Pay As U Go, Heartless and So Solid do it and become stars, why not do the same? The same was not true of DJing: several hundred pounds on a pair of Technics, a couple of hundred more on a mixer, more on some decent headphones, and then, after that, all the records: £5–10 for each new 12 inch, and about £25 to cut a dubplate. DJing isn’t cheap. MCing is free. ‘Everybody wants to be an MC, there’s no balance,’ as Wiley’s Pay As U Go-era bars observed. The posing, luxury brands and pimped-out stylings of the UK garage scene were being replaced by something much less aspirational, more raw, more hungry. In his autobiography, Wiley describes some of the few, frosty meetings in this transitional period between his rising east London crew, and south London’s reigning kings of UK garage:

‘Imagine seeing So Solid with all that fame, all that money, and then these bruk-pocket half-yardie geezers from east turn up with an even colder sound. There was no champs, no profiling, no beautiful people. Just us raggo East End lads in trackies and hoods, hanging out in some shithole white-man pub on Old Kent Road. We were realer in a way. We were just about spitting and making beats, that’s it. South must have thought we were on some Crackney shit.’13

Those bruk-pocket geezers from east would change everything. ‘I do sometimes wish more people respected what Pay As U Go did for grime,’ Maxwell D says. ‘Because Pay As U Go, that’s the grime supergroup. That’s like a grime atom bomb, exploding into all those little molecules.’ You can see what he means. Even though their album was never released, and ‘Champagne Dance’ was their sole official release, the personnel involved would go on to transform British music. Geeneus made piles of stunning instrumentals (under his own name and as Wizzbit) and was the chief architect of UK underground super-pirate Rinse FM, stewarding sibling genres dubstep and UK funky along with grime, signing Katy B and creating an ever-expanding collection of related businesses. Slimzee would become grime’s biggest and most respected DJ, the dubplate don par excellence. Maxwell himself would go on to join East Connection and later Muskateers. Target would make a number of sterling instrumentals for Roll Deep, and become an influential DJ on BBC 1Xtra. And then there was Wiley, the godfather of grime, who sprang from the short-lived excitement and disappointment of Pay As U Go to start Roll Deep, bring through Dizzee Rascal, Tinchy Stryder, Chipmunk, Skepta and create his ‘Eskimo sound’, perhaps the sonic palette most identified with the genre.

‘Don’t get me wrong, we weren’t there in isolation,’ Maxwell continued. ‘So Solid Crew were a big part of influencing the grime culture, but they were already superstars, and they were garage superstars. And Heartless Crew, they were doing garage and sound-system stuff, playing a bit of ragga, a bit of darker stuff – but for me, Heartless were always happy, they were about love and peace, whereas we always used to bring a lot more street lyrics. And underneath us, you’ve got all of east London immediately turning over to grime music. Because after us, who was next? East Connection, More Fire Crew, Nasty Crew, Boyz in da Hood, SLK. All these crews started emerging.

‘After Pay As U Go, that was when it all went dark,’ he smirks. ‘We turned out the lights.’

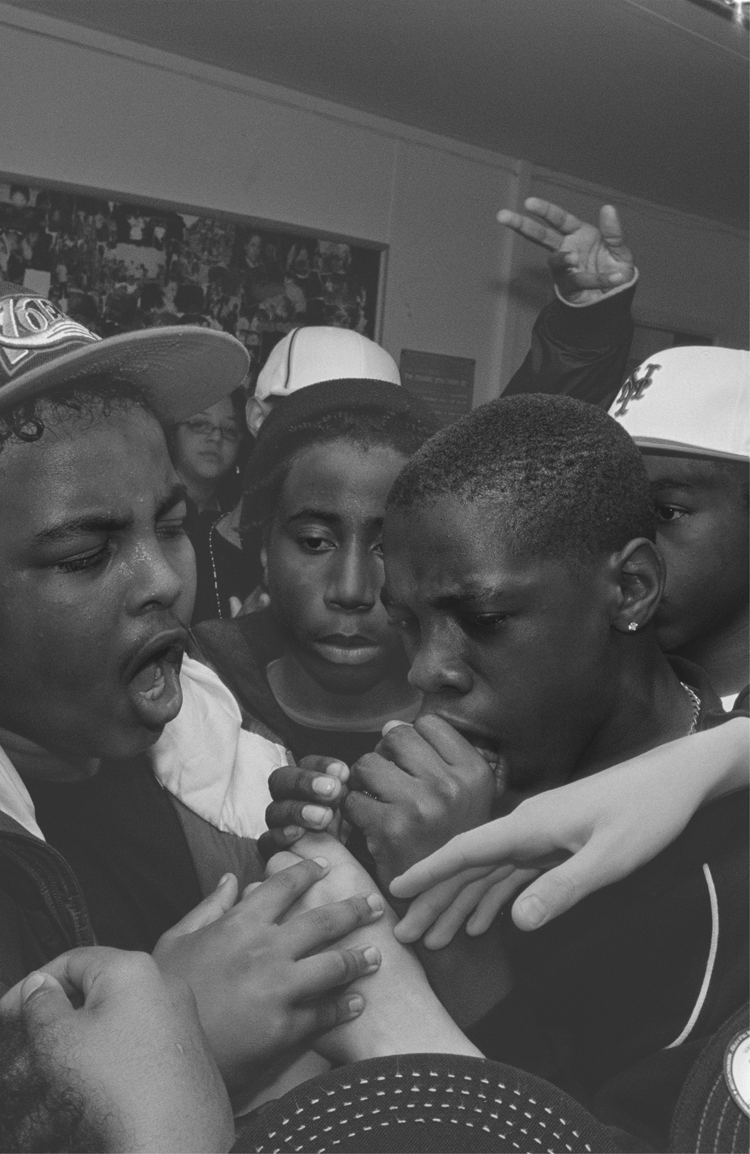

Pass the mic. Chrisp Street Youth Club, Poplar, 2005

THREE

THE NEW ICE AGE

If it takes a village to raise a child, it definitely takes a village to raise a scene. It’s one of the fallacies of the bedroom-producer trope in grime’s origin story, that a wild and pioneering auteur creativity was born out of solitude. Grime was created in bedrooms – but not alone, or in isolation: it didn’t allow for eccentric hermits, because the London it came from didn’t either: boroughs of densely populated flats on densely populated estates, where a tower block is itself a kind of vertical community, and both in it and around it, everyone knows everyone’s business – and their bars. The inner-city kids who came up through jungle and UK garage in the nineties learned how to DJ it, how to MC on it and how to dance to it together.

When they were ready to make their own sound, they taught each other, vibed off each other, and absorbed each other’s ideas and idioms, hanging out in vital if unglamorous hubs like Limehouse basketball court and Jammer’s parents’ basement. Shystie only started to write lyrics because her friends at sixth-form college pushed her to. ‘They taught me how to put words together, which instrumentals to spit over, and I’d spit in front of them. There was no YouTube, no Twitter, no SoundCloud, there was nothing – instead it was word of mouth: it was about getting big in your own area, your friends bigging you up, practising at sixth form with them – then you have other local schools, they would kind of support you too, because you’re seeing them on the way home; you’re building up your local fanbase, really. I started performing locally at parties, and my name got around more. I’d do little local raves, and it just spiralled and domino-effected and spread like wildfire. Those practice hours were so important man – I put in so many hours, it’s not a joke.’

School outside of classroom hours was instrumental – it was a key location, a vital node in the network, in an embryonic scene populated largely by teenagers and exclusively by under-25s, where local connections were everything. In a sense, it might be said to be the last truly local scene: these were the final years before social media and web 2.0 collapsed distances between strangers, and forged brand new kinds of instant networks across geographical boundaries. In grime’s formative years, it was the people who you knew from the area – neighbours, schoolmates, brothers and sisters – that created the platform on which a scene was built. Crews like Ruff Sqwad were formed through school in the first place, and MC practice took place in a group, in the playground – after school, during lunch break, whenever there was time. There’s a reason all those hood videos and ‘freestyles’ show the MCs with their crew and their mates gathered around them, whooping and popping gunfingers: because that’s how the bars are written, refined, practised and improved to begin with: it’s not so much a gathering for a performance, to camera, as an – albeit slightly exaggerated – mirror on the day-to-day reality of where the music comes from.

The story of grime in east London in particular is a dense family tree of friendships that initially preceded music, and then as the protagonists’ teenage years proceeded, developed because of it. When I asked Target about the lineage that led him to Wiley, and the rest of Roll Deep, it went back to primary school: by the age of ten, they were playing with the vinyl decks in Wiley’s dad’s flat in Bow, ten minutes from Target’s childhood home. ‘We literally didn’t leave the bedroom all weekend, we were just playing on these decks. We couldn’t mix or anything, but we were just having the best time ever.’ By the final year of primary school they’d formed a new jack swing meets rap group called Cross Colours, inspired by Kriss Kross and Snoop Dogg, and Wiley’s dad was taking them to meet an A&R.

By the mid-nineties, still only in their mid-teens, they were already veterans, and Target and Wiley formed SS (Silver Storm) Crew with Breeze, Maxwell D and others. They would hang out on Limehouse basketball court and practise their jungle bars, or go to each other’s houses to record tapes, streaming up the stairs of Slimzee’s mum’s house, where Geeneus and Slimzee were for a while broadcasting Rinse FM, illicitly – the authorities didn’t know, and nor did Slimzee’s mum. ‘She kept saying to me, “What’s going on up there?” Them times I was only young, so they didn’t really want me to go out – it weren’t a bad area, but … things was going on, you know? So they’d rather me stay in, than go out, taking drugs and all that stuff.’

More than one MC or DJ has recounted that, as much as grime would soon lyrically reflect the trials and tribulations of petty crime, drug dealing and violence, many of their parents supported their teenage musical experiments for the very reason that, if they were all making a ruckus in the bedroom, they weren’t out on the street getting up to no good. Tinchy Stryder’s older brother was a DJ and had turntables in the bedroom they shared in the Crossways Estate. ‘We all used to come back to my mum’s house and practise there. I’m always grateful to my mum and dad, because I don’t know if many people would’ve let loads of boys come in the house and make that noise,’ he laughed. ‘Because grime ain’t nothing calm, and it wasn’t a big house.’ So much was developed in childhood bedrooms with hand-me-down decks, or even less. In Shystie’s case, her mic skills were developed as a teenager with a karaoke machine and a £9.99 microphone from Argos.

That neighbourhood scene in the nineties thrived via word of mouth, pirate-radio broadcasts, and one critical performance arena: ‘The root of all this grime business, of grime MCing, was house parties,’ Wiley said to me in 2016, while recording The Godfather, his eleventh album (or fortieth, if you count all the mixtapes). ‘Proper house parties, with a proper system, all across Bow and Newham when we were teenagers. We’d go and jump on the mic, and clash each other.’ SS Crew would get invited to perform at any house parties around E3; they’d be walking around Bow carrying their decks and boxes of records.

‘That was the first taste of when you get that energy back from the crowd,’ Target recalled. ‘We couldn’t believe it, like, “Whoa, this is sick!” At that stage we didn’t ever think we could get paid, there was no future plan: just the excitement of participating. It was a sense of community, definitely, it was. At the time we wouldn’t have used words like that, but that’s what it was. We were all from the same area, loads of us were into music, DJing or MCing, and when Rinse started we actually had a base, and the chance to be heard by people who didn’t already know us. Going on Rinse and having a text from say, Stacey in East Ham, felt incredible – it was like going international. It was like having your track go Top 10 in Spain or something, it was that exciting.’

As London’s millennium wheel first began to turn, the sun began to set on UK garage, its glossy pop moment cast in shadow. The younger generation of MCs and DJs had had years of training on the mic and on the decks, but if they were being pushed out by their elders, the response was to turn their outcast status into something they could be proud of and control. Before it had acquired a genre name, grime’s young talents, those too young or too angry to feel UK garage was theirs, began creating a new sound, riffing on some of that weirder, darker garage, the kind with broken beats instead of 2-step’s shuffle and swing: the kind that was too awkwardly shaped to wear designer-label shirts and smart shoes to the club. They would eventually overwhelm British pop, doing so with the barest minimum of equipment, and in most cases with almost no formal musical training. They taught themselves and each other, and used software like Napster, Kazaa and Limewire to downloaded illegal ‘cracked’ versions of simple music production software like FruityLoops Studio. To begin with, that was the closest grime’s pioneers would come to a studio.

Grime, in its first years, sounded as if it had crash-landed in the present with no past, and no future – a time-travelling experiment gone horribly, fascinatingly wrong; a broken flux capacitor glowing amidst the smouldering wreckage, a neon light pulsing in the mist. While on one side of the A13, Canary Wharf’s tenants enriched themselves to dizzying new heights, the sounds emanating from the tower blocks barely a mile away declaimed through the airwaves that there was more than one east London. There was an alien futurism to a lot of the computer-generated aesthetics – the reason why some of the bleeps and bloops sounded like noises made by spaceships from computer games was because they were in fact made on games consoles: most famously a piece of software for the first PlayStation, called Music 2000. A lot of So Solid Crew’s first album was built on this very elementary software; as was Dizzee’s ‘Stand Up Tall’. Producers like Jme and Smasher made their first tunes on it, recorded them to MiniDisc, and then had vinyl dubplates cut straight from the MiniDisc – without going anywhere near a recording studio.

Mixdowns are usually seen as a crucial stage of the recording process even for the most entry-level producer, where the elements created are refined and balanced out to create a clean and coherent whole – but with grime they sometimes didn’t happen at all, before the tunes were cut to vinyl and released, either as dubplates or for general release to record shops. This applies even to the instrumental frequently cited as the first proper grime tune, Youngstar’s ‘Pulse X’. The spirit of the period echoes the famous punk mantra, ‘Here’s a chord. Here’s another. Here’s a third. Now form a band.’

DJ Logan Sama, for one, was happy enough with the devil-may-care approach to technical proficiency. ‘I don’t give a shit if a record is mastered well or not,’ Sama said to me back in 2006, then a new graduate from the pirate-radio scene to the legit world and new sofas of KISS FM. ‘All I care about is the reaction it gets when I play it in a club. How technically well-made art is doesn’t matter: it’s art. Why would you want to analyse it on its technical merits? It’s not an exam. My white label of “Pulse X” still has the hiss from the AV-out cables from the PlayStation they took it off to record it onto CD, when they took it to master it.1 You can hear it! The ‘bawm’s are all distorted. That record sold over 10,000 copies; it was fucking massive. Half of So Solid’s first album was produced on Music 2000, they then took it into the studio on a memory card to re-engineer it. That album sold over one million copies. A lot of people loved jungle when it was shit – when the quality of it was shit! Personally I like “jump up” stuff, and if I get that out of a technically well-made record, then cool; if I get that out of a record that’s been made on FruityLoops and not mixed-down properly, so be it.’