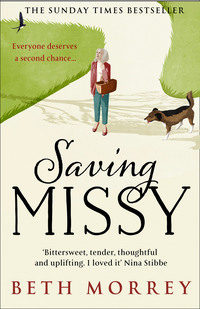

Saving Missy

‘Even if someone beats you black and blue?’ piped up Henry.

‘Even if they do that!’ retorted Fa-Fa, ruffling his hair. ‘Even if they cuff you,’ he tweaked Henry’s ear. ‘Even if they thump you,’ he aimed a mock punch at Henry’s stomach, then again a little harder. ‘Even if they bash the hell out of you, you hang on!’ He and Henry began play-fighting, but as the bombs started up again, the frolic became something else. Fa-Fa had Henry in a headlock, my brother’s face a livid red, eyes sparkling with excitement or tears, I couldn’t tell which. Jette stood, holding out her white handkerchief.

‘Father! What are you doing?’

My mother had slipped in through the cellar door, unnoticed. She was unwinding a scarlet scarf from her neck, pale from the cold and angry as usual. Jette rushed forward to embrace her, but Mama ignored her, still glaring at my grandfather. Fa-Fa looked up and released his hold on Henry, who fell back on the bunk, his hands at his throat.

‘When will you learn to be gentle around the children? They’re not your recruits. I suppose you’ve been telling them awful stories again. Now, Milly, Henry, let’s get you in bed, it’s far too late for you to be up.’ She began the motherly round of tucking us in, picking up our half-eaten pieces of bread and leaving them on the side for morning.

Fa-Fa retreated to a chair in the corner to pack another pipe, sulking, as Mama lay down on her pallet. The last thing I remembered was her blowing out the final candle, and the comforting smoulder as Fa-Fa smoked the night away. Then the ink-blot shadows on the walls sent me into a deep sleep that even the booms outside couldn’t penetrate.

The next night, an SC250 landed in the road outside our house, reducing the garden wall to rubble. No one was injured although Fa-Fa’s spectacles fell and shattered in the blast. After that, my mother decided we would be better off in the country and packed us off to my Aunt Sibyl in Yorkshire. But it seemed the decision wasn’t so much based on the bomb as the story of the bag, which Henry recounted to Mama the next morning, provoking another tirade. Fa-Fa was reprehensible, telling disgraceful stories which probably weren’t even true (Jette wouldn’t confirm or deny when asked), it was high time we got some country air, etcetera. So off to Kirkheaton we went, to a draughty old rectory where we slept in the garret, searched priest holes for ghouls, made dens in the woods and mostly forgot about the war and Fa-Fa’s strange habits.

We didn’t forget that story though, and used to tell it back to each other, lying in those hard narrow beds under the eaves. Each time, we’d add an embellishment – a dramatic flourish, some sordid detail, until eventually we weren’t sure where Fa-Fa’s tale ended and ours began. Did he make it up, or did we? Did any of it happen, or none of it? As the years passed, I was inclined to believe the latter.

Still, it’s true though, isn’t it? If you really want something, you hang on.

Chapter 4

A week went by without anything happening that I could put in an email to Alistair. I hardly left the house, except to get a few bits – a scrag end at the butchers, a prescription from the chemist. I thought Sylvie was in front of me in the queue and bent my head so she wouldn’t notice me, but it wasn’t her at all, just some other middle-aged woman buying indigestion tablets.

I splashed out on a bottle of wine on the way home, though drinking on my own seemed like a slippery slope. But the evenings stretched, and a glass of something gave the synapses a sly tweak, lending a little ‘entheos’ – the Greek buzz of enthusiasm. Just the one glass, maybe two small ones, distracting myself from the rest of the bottle by poking around various rooms in the house, most of which were hardly ever used any more. What did I need a dining room for? All those dinner parties?

The dust in Leo’s study gave me a coughing fit. I should really pack up the books and get rid of them, but he would have been horrified; most of them were first or rare editions and I didn’t know enough about them to be sure of getting a decent price. So instead I wiped them, and read the inscriptions: ‘Darling Leo, Christmas ’86, with love’; ‘Leo, read this and please be kind – Asa’; ‘Dad – another old tome for you – Mel’. ‘Tómos,’ meaning ‘slice’. Each book a slice of the man. None of them were mine. I stopped reading when the children were born.

One night and another visit to the vintners later, I found myself in Alistair’s room, still as it was when he was a boy. His Arsenal posters, his Lego models, his fossils. My son, the archaeologist! The room was like one of his sites; the artefacts and remains of some revered Pharaoh. And now the next in line slept here – I smoothed the pillow where Arthur’s golden head had lain. How I missed him. A gap in the shelf where the first edition should be.

The day Ali left home, we drove him to his halls, Leo chuntering about red-bricks, while I was speechless with the effort of not crying, smiling as we unloaded his bags and settled him in that dingy little room, as if it were just wonderful to think that he was going off into the world to make his own way. What an adventure! Just at the end though, when we said goodbye and he hugged me, I found I couldn’t let go. Eventually, Leo gently prised my fingers from Alistair’s sweater and gave them a reassuring squeeze. ‘He’ll be back at Christmas,’ he said heartily. Christmas, always Christmas – casting its fairy lights on the banality of every other day.

I went to the fridge again, then to Mel’s room to pack up a few of her books. She had her own flat in Cambridge, and it wasn’t like she ever visited any more – not since that terrible afternoon. After checking the cupboard doors on my way to bed, I remembered the lights were still on in the living room, so had to drag myself downstairs again. As the room flicked into darkness, the street outside was illuminated, revealing a young couple wrapped around each other, making their way home after a night out. Her teeth glinted in the lamplight as she smiled up at him, tucking his hand more firmly under her arm as he kissed the top of her head. Lithe and blithe with most of their mistakes unmade. It might have been Leo and me, half a century ago. I closed the curtains, did another round of checking and reeled off to bed.

The next day, nursing a headache, I went to the chemist again, and again saw a woman who looked like Sylvie, only this time it was Sylvie. I ducked, but it was too late.

‘There you are!’ she exclaimed, as if I’d only been gone five minutes. ‘You rushed off the other day. How are you feeling?’

‘Fine, thank you.’ I shuffled forward in the queue, hoping she wouldn’t notice the paracetamol, which I always used to hide from Leo. A hangover was an admission of guilt. If I didn’t have one, then I hadn’t drunk too much the night before.

‘Snap.’ Sylvie nudged her box against mine. ‘I’ve got the most god-awful monster behind the eyes. All self-inflicted, of course. Angela can really put it away. She’s a hard-drinking journalist. What about you?’

She had the air of everything in life being a tremendous joke, a flippancy that made me want to kick off my shoes and talk of cabbages and kings – to be in a world where things didn’t matter so much. But all I could manage was a weak shrug.

‘Fancy a coffee?’ She nodded at the café opposite. It looked as warm and inviting as Sylvie herself, all low lamps, metro tiles and bare wood. There was the row of workers at their laptops, bashing away; two mothers with prams, heads together as they coochy-cooed at their offspring; a couple deep in conversation, their hands entwined. I didn’t belong there, amidst all that companionship and industry, and had no idea why Sylvie would offer such a thing.

‘Oh thank you, but I really must be going.’ I handed over my coins and reached for my paper bag of painkillers.

‘All right, well, see you soon, hopefully. Millicent.’ She remembered.

‘It’s actually Missy,’ I blurted, as she pulled open the door. It tinkled merrily and she turned back with a raised eyebrow.

‘I’m sorry?’

‘Well, my name is Millicent, but everyone calls me Missy,’ I floundered, dropping my change, feeling the heat building in my face.

‘Oh, right, well, Missy it is! I’m sure I’ll bump into you again, I’m always around,’ Sylvie waved and exited, wielding her wicker basket like a 1950s housewife.

I left the chemist, flustered and overset. No one called me that. Not since Leo, and before him, Fa-Fa. She must have thought me completely doolally. Cheeks still burning, I found myself walking across the road towards the café. If she was there I’d jolly well have a coffee with her, stop being so silly.

The workers were still tapping away, the mothers clucking over their babies and gossiping, but the couple had gone. There was no sign of Sylvie, but I ordered a coffee anyway and sat at a table, feeling stiff and embarrassed, sure everyone was watching me, wondering why an old lady would come in here on her own. But no one seemed to notice, and gradually the warmth and noise of the place started to sink in. Someone had left a newspaper on the next table. I took it and read about Jeremy Corbyn, who lived nearby, and the astronaut Tim Peake, living much further away, and Alan Rickman, not living anywhere any more. He was in one of Leo and my favourite films, about a ghost who tries to cheer up his bereaved wife. I was a bit like Nina, the wife, wandering around my empty house in the hope of a miraculous resurrection. I always thought she was wrong not to stay with her husband Jamie, even though he was dead.

I stayed there for a while, sipping my coffee and reading the paper, and when I’d finished, the smiling waitress collected my cup, the mothers shifted their prams for me, and a man left his laptop to hold open the door. I walked home slowly, noting the pine needles that still littered the pavement but occasionally holding my face up to the weak winter sun.

When I got back, rather than embark on my usual round of cleaning, I went upstairs to the spare room and brought down an old paisley throw, draping it experimentally over the sofa. Then I went back up and fetched a lamp, placing it on a low stool to one side. I stood contemplating it for a while, then, feeling faintly foolish, went into the kitchen to make myself a cup of tea.

Later on though, when the light faded, the lamp and blanket looked rather snug. I skipped cereal for once and cooked myself some pasta, eating it off a tray on the sofa while I watched some new period drama. Leo would have scoffed at the anachronisms, but it was a relief to be pulled in by gentle domestic tribulations. I considered rounding my evening off with a glass of wine but remembered I’d finished the bottle the night before. Ah well, I could always buy another tomorrow. Who knew who I’d bump into?

I still didn’t have much to write to Alistair about, but at least I’d been invited for a coffee and went, in a way. Baby steps. Old lady steps. Even if I wasn’t quite sure where I was going.

Chapter 5

Down, down, down, and it’s 1956 and I’m in Cambridge, kneeling on the floor trying to make a fire.

There I was, Milly Jameson, in my second year at Newnham College, miserable in a freezing room, pretending I enjoyed reading Homer. The other students were so glamorous, shrieking down the long corridors and sneaking men into their rooms. The girl next door to me was garrulous and captivating, my polar opposite. Tiny and curvy, with tinted blonde hair set in perfect waves, she kept a bottle of gin under her bed for ‘Magic Hour’ cocktails served to her numerous guests. Alicia Stewart and her legendary soirées – every night, I heard her gramophone and banged on the wall as she sang to the tune of ‘Mr Sandman’: ‘Mr Barman, bring me a driiiink … Make it so strong that I can’t thiiiink.’ I had no idea how she intended to get a degree – probably by charming the exam paper into submission.

However, Alicia’s fearsome cocktails were one of the few things that allowed me to unbend, so we had become friends of a sort, or at least she facilitated my drinking habit. My room had a window that opened handily onto a lean-to, serving as an escape route for those who found themselves locked in college after hours, so in return for the odd tipple, I permitted her to smuggle her gentlemen friends out. She swore there was no more going on than heavy petting, as if I were in any way an arbiter in these matters, being as far from ‘necking’ as I was from singing with The Chordettes.

Midway through the second year of my degree, it was becoming apparent that I was not the gift to the academic world I’d imagined. My supervisor described me as ‘a skimming stone’, which was fair – who wanted to contemplate the depths? In the eleven years since my father died, I’d become particularly adept at disregarding deeper waters.

Rather than wrestle with ‘Catullus 85’, ‘Odi et amo’, I was sitting on the threadbare rug that chilly February evening, trying to coax a flicker in the grate. We were in Peile Hall, a draughty old building where they had yet to install gas heating. Instead there were these metal sheets we held in front of the fireplace to draw the air – Sydneys, they were called – but there were only two to go round all of us. We had to traipse along the corridors knocking on doors to hunt one down, so when there was a knock on my own door I assumed it was someone after the Sydney. Instead it was Alicia, already three sheets to the wind, propping herself up against the doorframe.

‘Milish … Mishilent. What’s that smell?’

‘Smoke. I’m trying to light a fire.’

‘Why?’

‘Because it’s cold.’

‘Is it? Never mind. There’s a party. For a new poetry magazine.’

‘Oh good. Have fun.’

‘No. You have to come with me.’

‘Why?’

‘Because I can’t find it.’

‘I’ve got nothing to wear.’

‘You can borrow something.’

‘I don’t feel like it.’

‘There’ll be wine. And it’ll be warm.’

Which was how I found myself, wearing one of Alicia’s black dresses that was too short and big in the bust, tottering through the streets of Cambridge as we searched for the Women’s Union in Falcon Yard. When we finally got there, I wished we hadn’t bothered. So loud and dark, with pockets of light illuminating the jazz band, and people reciting verse that made me cringe. I’ve always found poetry – particularly the reading aloud – excruciating. Like religion and Bongo Boards, best practised in private.

Alicia weaved off and disappeared, so I went in search of the wine she’d promised. At least it was warm, with all those people, all that hot air. There was a poet standing in the corner, head flung back as he declaimed to an earnest little throng – something about buttocks and crystals. Good Lord, it was awful.

I stood with my back to the wall, gulping wine, examining my lack of cleavage and wondering how soon I could escape. And then, across the room, there he was. Like everyone else, he was drunk. But he was the only man wearing a suit, rather than a turtleneck, and that, along with his height, made him distinguished. He saw me, and grinned as though he knew me, and that moment was a homecoming. He ambled over, still smiling. Then, as he drew nearer: ‘Oh, gosh, sorry! I thought you were someone else!’

Up close, he was even drunker than I thought, swaying like a great oak in a gale. But he was very handsome, big and blonde, a Labrador of a man, and I was emboldened by the wine.

‘Who else do you want me to be?’

I’d always been a terrible flirt. I just couldn’t do it, even with lubrication. Luckily it was so loud in there, with the jazz and the poetry and people smashing glasses, that it didn’t seem to matter.

‘Well, since the girl I thought you were doesn’t seem to be here, shall we have another drink?’

He led me over to the long table stacked with bottles, and poured me a glass while I tried to think of something clever to say.

‘It’s a terrible name for a magazine, St Botolph. Sounds like something to do with church,’ I blurted. Oh blast, he was probably one of the editors. But he just laughed.

‘I know, but this party puts paid to that notion. Definitely nothing godly about it.’ He dodged a wine bottle as it sailed past. ‘Do you like poetry?’

‘Not really. It’s a bit self-indulgent for me.’ I didn’t know why I was so forthright all of a sudden. Probably the alcohol, but also a strange sense that I couldn’t stop myself unfurling – a flower opening up to the sun.

‘Really? What do you study?’

‘Classics. But I’m more of a prose person generally.’

‘Tell me something you like.’

I looked around the room. ‘One half of the world cannot understand the pleasures of the other.’ I felt very erudite.

‘Ain’t that a shame,’ he replied, reducing me to gauche schoolgirl again. Across the room there was a couple ferociously kissing, or wrestling, I wasn’t sure which. I had to do something spectacular, be spectacular, so that he would remember this point, and when people asked how we met, we would be able to say, ‘now, there’s a story …’

Instead, Alicia Stewart chose that moment to re-enter the room, waving a glass of wine, tripping over a discarded bottle, grabbing a tablecloth to break her fall and vomiting spectacularly over her old black dress, with me in it. The poet stopped reciting for a second, looking at us curiously, then resumed his discourse on bloated knaves.

‘Shit.’ She lay on the floor, drops of red wine caught on her eyelashes like beads of blood. Roaring with laughter, my knight stooped to help her to her feet. In the circle of his arms she looked up at him admiringly.

‘Oooh, you’re nice!’ Alicia exclaimed. She shifted her glance to me. ‘Milly, you’re covered in sick. You look dreadful. You should go home before you disgrace yourself.’

I glared at her and used the tablecloth to wipe myself.

‘I shall have the honour of escorting you both,’ said our hero, offering us his arms.

‘Lovely,’ slurred Alicia, grabbing hers like a drowning woman. ‘I’m Alishia and this is Milish … Milish … Misha.’

‘Hello, Misha. I’m Leo.’

‘Ooooh, Leo the lion!’ she crowed. ‘Take us back to your lair, Leo!’

We picked our way through the broken glass, swiping a half-empty bottle of wine along the way. Outside in the corridor a girl was sobbing and being comforted by a bony young man who kept patting her shoulder, saying ‘Don’t worry, he was a sod anyway.’ He was always going to be the friend who picked up the pieces.

Outside we could see puffs of our breath in the frigid air as we weaved through the cobbled streets. The sky had cleared, and when we emerged on to King’s Parade it was swathed in a velvety blanket of stars that winked above the chapel. Even they were mocking me.

As soon as a decent interval had elapsed I dropped Leo’s arm and fell behind so they could walk together. But I kept the wine. The streetlamps caught the golden tints in Alicia’s hair as she gazed up at him, doing that tinkly little giggle she affected with men – her real laugh was more of a charlady cackle.

We crossed the bridge on Silver Street, and I looked down at the sluggish River Cam, remembering how I’d imagined Cambridge would be all punting to Grantchester, and cycling through quads with my gown flapping in the breeze – skimming stones that barely rippled the waters. Instead I got the bolt at St Botolph’s, following my sozzled neighbour home in the early hours, covered in her sick, while she seduced someone I saw first. ‘Odi et amo’. Draining the last of the bottle, I threw it in the river and watched it slowly sink into the depths. I suppose it’s still there somewhere.

Chapter 6

The following Tuesday, there was a fight at my new café.

After my encounter with Sylvie in the chemist, I took to loitering around that row of shops, the café in particular, until the smiling waitress began to recognise me and serve my coffee with plain cold milk, none of that frothy nonsense. They gave me a little card that got stamped every time I bought a cup, eventually resulting in a free drink. The bread in the Turkish shop next door was cheap and fresh, and I browsed the children’s fiction in the charity bookshop, picking up a Thomas the Tank Engine book for Arthur for fifty pence.

I’d never bothered with any of these local explorations before – I’d been busy with the children and running the household, and later, when he got ill, looking after Leo. I didn’t have to worry about money then either, whereas now I spent my time rooting out meagre bargains as if it would make the slightest difference. My meanderings whiled away the hours and the pennies, but there was still no sign of Sylvie.

That Tuesday, enjoying my regular ‘Americano’, who should come in but Angela, this time without Otis. She was unkempt as usual, tendrils of too-red hair escaping from a topknot, smudged eyeliner, leather jacket and scruffy boots with buckles that clinked as she walked. At first I didn’t notice the woman she was with, but as they sat down together in the corner I saw she was crying, and that Angela appeared to be comforting her. She was speaking quickly, persuasively, but the woman kept shaking her head, wiping at her cheekbones. She was terribly thin, with a sucked-in look that led me to conclude she was probably on drugs.

Then Angela suddenly sat back, smacked the table like she was finished, and the other woman got up and cannoned her way out of the café. Angela half-stood up and called out something that sounded like ‘Flicks!’ but maybe she was just cursing. The woman stopped in the doorway and turned around, mascara in streaks down the hollowed panes of her face, her mouth twisted into a snarl.

‘You don’t get it,’ she snapped. ‘You’ll never get it.’

They both seemed oblivious to the other customers, who had fallen silent at the spectacle, watching over the rims of their cups as they appreciated this little soap opera scene.

‘I want to help you,’ said Angela. ‘Please.’ She held out a hand.

Like a tennis match, all eyes darted across to the other woman in the doorway.

‘Then stop interfering. Leave me alone,’ she spat, reaching for the door handle. What happened next was extraordinary. Angela leapt forward and pushed the door shut, barring her way; the woman tried to shove her aside, and they grappled in the entrance, pulling each other this way and that. Occasionally one of them would say, ‘no!’ or ‘don’t’, as they continued their ungainly shuffling, oblivious to the dropped mouths of the onlookers. Then the other woman suddenly lifted her hand and slapped Angela across the face. She fell back with a short cry and there was a collective gasp from the customers; one of the row of laptop-workers stood up, as if to protest, then thought better of it as Hanna the waitress hurried forwards and pulled Angela back a step. The other woman watched them for a second, chest heaving, hair askew, then wrenched the door handle and stumbled out into the street.

There was a barely perceptible sigh of disappointment as she exited – the fun spoilt when it was just getting going – but I’ve always found such public displays sordid. Leo and I once had an argument at a party, sotto voce out the sides of our mouths, lifting our glasses and nodding to passing guests. People have no standards nowadays; they just let it all hang out.

Angela, a livid mark on one cheek, sank into her seat, took a cigarette packet out of one pocket and lit up right then and there. Hanna went back over to remonstrate with her. Grimacing, Angela stubbed out the cigarette in a saucer. She sat with her head in her hands for a while, then picked up her bag and made her way to the door. As she passed my table she caught sight of me and raised her eyebrows wearily.

‘Oh, hi, er …’ Unlike Sylvie, she’d forgotten.

‘Millicent.’

‘Hi, Millicent. You OK?’

‘Fine, thank you. Um … you?’ To my dismay she suddenly hefted her bag on to the floor next to me and took the seat opposite, beckoning Hanna over to take her order.