The Doctor’s Kitchen - Eat to Beat Illness

+ Stress-relieving techniques As an adjunct to improving stress hormone levels and reducing inflammation, stress-relieving techniques and mind–body interventions including deep breathing exercises, meditation and yoga can have positive effects on heart health. It may seem slightly leftfield for a conventionally trained doctor to be recommending this, but actually mental stress has been shown in many studies to be a significant contributing factor to heart disease.67, 68 Stress activates the immune system to create an inflammatory environment as it perceives the body is ‘under attack’ and this can lead to oxidative stress that damages and weakens blood vessels. These same stress hormones can increase sugars in your bloodstream, which can impact fat production by the liver as well as cholesterol ratios. There are robust clinical reasons behind why one of the most effective lifestyle programmes for heart disease, the Dr. Ornish Program for Reversing Heart Disease, has an intense focus on stress-relieving techniques. We would all benefit from one of these in our daily routine and you can check the website www.thedoctorskitchen.com.

+ When we eat The timing of when we eat has been shown to have a significant impact on our blood sugar, cholesterol ratios and the overall impact on our heart health.69 It is an unfortunate and well-recognised fact that shift workers who experience regular disruption to their circadian rhythm (the rough 24-hour cycle that all our cells are aligned to) have a greater risk of heart disease, obesity, dementia and generally live shorter lives.70 However, there are certain practices that even shift workers can employ to mitigate the effect of cycle interference. Studying this population of workers has led to some interesting recommendations that even those who are lucky enough not to have to do odd working patterns can employ. As a guide, it has been suggested that night-shift workers should eat at the start of their shift (dinner) and at the end (breakfast) to minimise the negative impact of eating when their bodies should be asleep. This practice of ‘defining periods of eating’ to a rough 10–12-hour window (during hours that you are awake) has also been shown to have favourable effects on markers of disease risk.71–73 As a general rule of thumb, this practice allows cells of your liver, pancreas and gut to better tolerate the food you ingest so that it is less likely to cause blood sugar spikes and cholesterol imbalances which can affect your heart. It’s a simple guide that not only gives your gut a rest (allowing it to perform the numerous other functions it needs to do) and minimises disturbance to your important rhythms, but also it also discourages mindless snacking in the late evenings that most of us do out of boredom.

These simple diet and lifestyle practices are incredibly powerful and accessible to the entire population. Combining these with the other chapters that demonstrate how to improve your immune system, balance inflammation and relieve stress produces a collective medicinal package that is so powerful in the fight against the biggest killer in the UK today. Our food and lifestyle are powerful tools that I encourage you to use, whatever your age for the optimal functioning of this principal organ.

Inflammation

It’s amazing how many times I see ‘inflammation’ as a concept coming up in different medical specialities as one of the potential causes of disease. It has almost become a unifying theory that links conditions of the modern world to our lifestyles. You might think I’m just talking just about the swollen ankle that happens after an injury, or the redness that surrounds a cut on the skin, but high blood pressure, heart disease, dementia, diabetes and mental health problems all have links to an imbalance of inflammation in the body at a cellular level.75

WHAT IS IT?

I see many products being labelled as ‘anti-inflammatory’ and I think there is a lot of misunderstanding about what inflammation really is. This chapter will give you more of a tangible idea about the role of inflammation in our health as well as how to tackle the problems related to an imbalance of this essential system.

Inflammation is your body’s normal response to events that cause damage to cells, like an injury or infection. The process involves proteins being released in response to the damage and these proteins send signals to the cells of the immune system to come and help. This is usually a short-lived, adaptive response that involves coordination of many complex signals and organs.74

The inflammation process is very important: without it our cells would not be aware of bacteria causing something like a simple skin infection, and leaving the bacteria undetected in our body could lead to an uncontrolled severe infection with significant consequences. Inflammation is critical for infection prevention and to keep the body alert. We have, in essence, evolved to be able to fight infections, and a host of other stressors to the human body, effectively and swiftly using inflammation as an important tool.76

However, inflammation is meant to be a temporary, protective response. Whether that’s a reaction to a knee injury or an infection in your digestive tract, inflammation is essentially a big nudge to your body, letting it know something is not quite right and needs to be addressed swiftly. Inflammation is meant to be a short-lived process that resolves over hours, days or, at worst, weeks. However, what we are witnessing in modern society is persistent, low-grade inflammation over longer periods of time, also referred to as ‘meta-inflammation’.77 Today we have a number of seemingly small and insignificant stressors that create subtle inflammation over long periods of time and can manifest in a multitude of symptoms. These range from the subtle and vague, such as fatigue, lack of mental clarity and skin irritation, to the more pronounced, including pain, mood disorders and heart disease.78, 79 These symptoms will obviously overlap with other causes, but we are becoming more aware of the damaging effects of inflammation imbalance that is at least in part to be related to these and many other conditions.

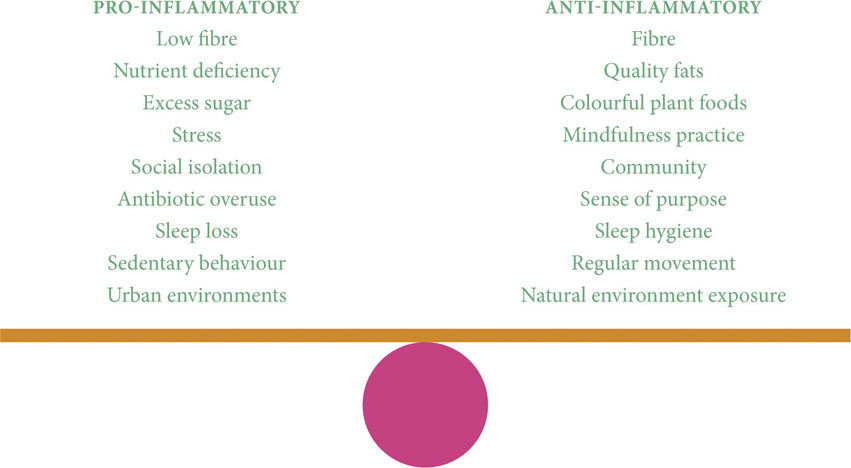

Examples of stressors potentially causing low-grade inflammation include excess sugar consumption, psychological stress, sedentary behaviour, accumulation of fat tissue and nutrient deficiencies (including vitamin D, Omega-3 and different micronutrients). Depending on our ability to tolerate these factors, the result can be low-grade meta-inflammation. This culmination of seemingly insignificant stressors can potentially tip us into a pro-inflammatory state, putting us at risk of the wide spectrum of conditions that inflammation is related to. This pro-inflammatory imbalance is what I will refer to as ‘inflammation’ for the rest of this chapter and what can be rebalanced with delicious foods and an enjoyable, healthy lifestyle.

While I want you to appreciate the importance of inflammation as a necessary mechanism in our body, when we examine the triggers of inflammation in modern life using this diagram, it becomes obvious why the balance of inflammation has become skewed towards the pro-inflammatory side of things. This meta-inflammation, as I’ve alluded to, has a role in many conditions including mental health disorders such as depression,78 high blood pressure80 and insulin resistance which is linked to the development of poor sugar control and ultimately Type 2 diabetes.81, 82 With this in mind, it’s important to try and find effective ways to prevent this imbalance from occurring and the diagram gives us an idea of what we can do to restore the equilibrium.

STOP THE TRIGGERS

The reassuring fact is that we can manage inflammation effectively and simply with changes to what we eat and how we live. It’s not expensive, it doesn’t require excessive interventions or huge modifications and I’m here to guide you through this process. We have many solutions within our control that we can broadly categorise into two steps. The first is to stop the pro-inflammation triggers in the first place. The second is to introduce diet and lifestyle changes to actively reduce inflammation; we possess the ability and mechanisms to purposely reduce the inflammatory response as well.83

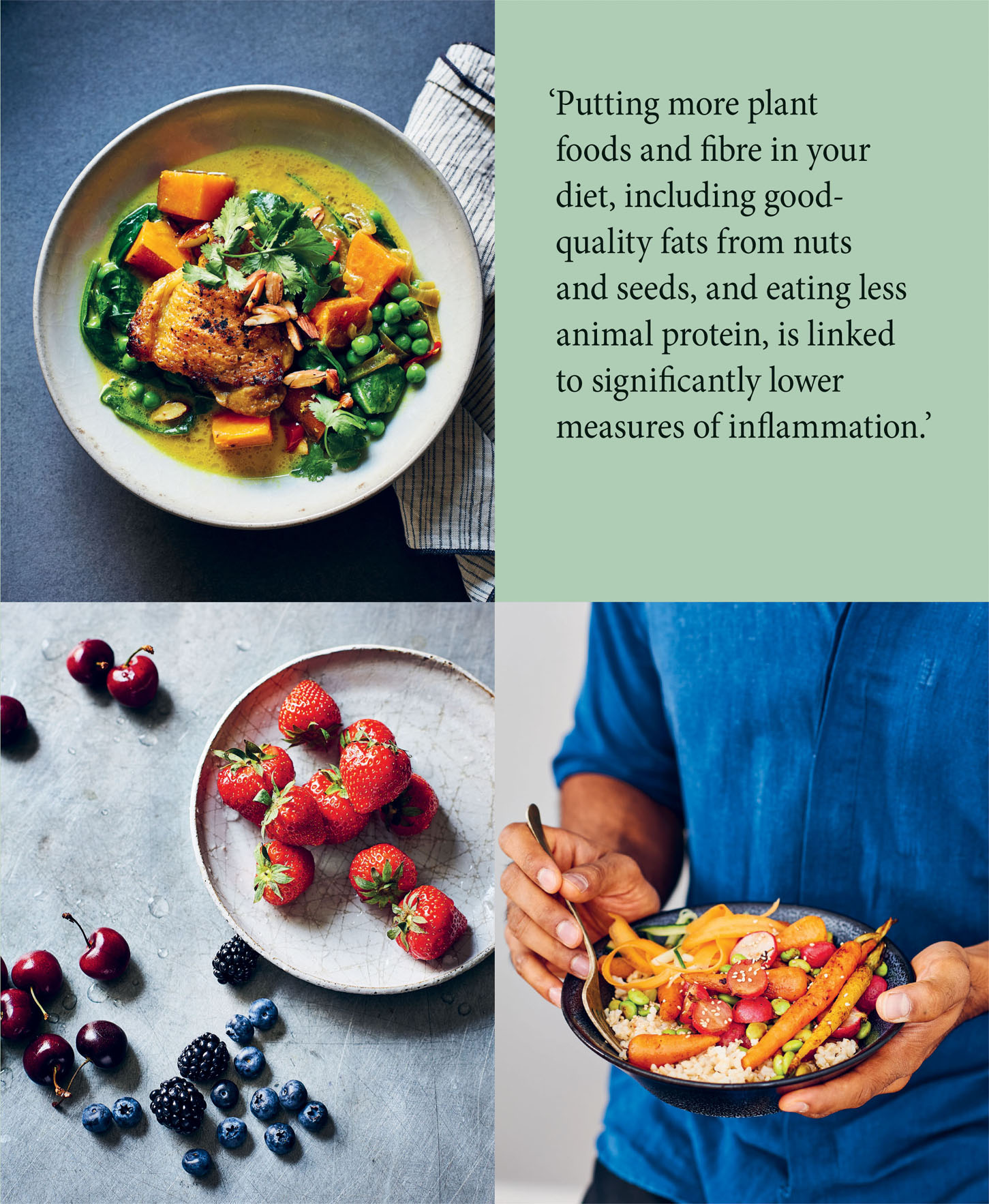

The most effective way to STOP inflammation in its tracks is by assessing our diet, which in many cases is the most obvious and clear trigger. Looking at a number of large population studies, the benefits of eating a largely vegetarian diet, from the perspective of reducing inflammation, is undeniable. A number of researchers have demonstrated that eating a western diet made up of refined sugars and carbohydrates, large amounts of animal protein, processed foods and poor-quality fats is related to higher amounts of inflammation signals when measured in the blood.84

Conversely, putting more plant foods and fibre in your diet, including good-quality fats that we obtain from nuts and seeds, and eating less animal protein, is linked to significantly lower measures of inflammation.85, 86 Essentially, it is a fairly Mediterranean-style of eating and we can reasonably infer from these studies that reduced inflammation is related to less disease and general health protection.85

EXCESS BODY FAT

Fat, also known as adipose tissue, is a very useful part of our bodies that we have required during our evolution. Without fat, we wouldn’t have survived long periods where food was scarce. This explains why those who have a genetic predisposition to putting on fat, particularly around their organs and waists, may have actually been at an evolutionary advantage when it came to harsh winters, famine and lack of nutrition for energy.87 Essentially, it would have acted as a storage form of energy that was readily accessible when food was not available.

Today, however, the ability to put on and retain fat is a clear disadvantage considering our current food environment full of ‘convenient’, energy dense and nutritionally poor options. With no famine around the corner there isn’t any use to carry fat on our body and we do not end up burning it for energy. To add insult to the situation, if we do accumulate fat predominately around our organs and waistline, it is ‘metabolically active’. That is to say, it promotes inflammatory signals that can contribute to the burden of diseases we’ve mentioned.88 This is why the scientific community promote ‘weight loss’ and reducing ones’ body mass index (BMI) as a strategy to counter the effects of excess fatty tissue.

While I agree that fat tissue is pro-inflammatory and people who lose fat can reduce their inflammatory burden,89 a narrow focus on weight alone is sometimes a negative goal for a lot of people who struggle to understand the wider context. I believe health can be independent of weight. It is your lifestyle, mindset and diet that are the biggest determinants of a happy, healthy life. I’d rather you focus on building healthy habits with wellbeing as your main goal, rather than a number on a set of scales. When you adopt a diet that reduces refined sugars and carbohydrates and replaces them with fibre, largely plants and colourful vegetables, coupled with the lifestyle changes I discuss throughout this book, you are lowering inflammation.90 These are also the habits that can protect against the dangerous type of fat accumulating around our body’s organs (known as visceral fat) that promotes inflammation and leads to health problems. Before we naively use our scales as a measure of success, I implore you to embrace healthy habits and the subjective measurement of how you feel as a better marker of health.

‘A diverse, plant-focused diet with plenty of fibre and a variety of colours is the easiest and most effective way to support your microbes anti-inflammatory ability.’

SUPPORT YOUR GUT

We are in constant communication with our environment via our digestive tract and so it should come as no surprise that inflammation is heavily influenced by the microbes living in our gut.91 Our microbiota, the different types of microbes such as bacteria and fungi living mostly in our gut, are important modulators of inflammation. A diverse and healthy population of microbes is associated with lower levels of inflammation and there are a number of mechanisms behind how they achieve this.

Your gut microbes support inflammation balance by increasing antioxidant production and reducing oxidative stress. They maintain the health of the tissues in your digestive tract to lower gut inflammation, which reduces the likelihood of foreign material inappropriately passing into your bloodstream, causing your body to react. Your microbes protect you from infections and improve your ability to control sugar in the blood, plus they actively secrete chemical signals that calm your immune system, preventing an inappropriate inflammatory response. These, and a number of other mechanisms, are why a flourishing, diverse population of microbes is so important from the perspective of balancing inflammation 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 63 and as you’ll discover as you read on, the most effective way of nurturing a healthy microbiota is with your food.

There is huge scope for introducing specific bacterial strains to counter the ill effects of inflammation, and some studies have had promising results using probiotics (live bacterial strains in supplemental form).63, 97 But, before you reach for specifically designed strains of bacteria that are formulated with ‘anti-inflammation’ claims, let me remind you that your microbiota is best served by a diverse, plant-focused diet with plenty of fibre and a variety of colours. This is the easiest and most effective way to support your microbes’ anti-inflammatory ability.

What follows is a description of lifestyle changes and foods that support your bugs, prevent fat accumulation and balance inflammation through a variety of pathways.

+ Good-quality fats It’s long been thought of as a hindrance to health and wellness to have any fats in your diet because of fears of weight gain and risks to your heart, but once again it comes down to the quality of the fats in your diet rather than purely the amount. Dietary fatty acids from oily fish and nuts can positively impact inflammation by changing the expression of your genes, influencing the inflammation pathways within cells. They’re also the building blocks of molecules that are used to signal your body’s anti-inflammatory response.98, 99, 100 Whole sources of fats from plants such as walnuts, macadamia, pumpkin seeds, sunflower seeds and of course extra-virgin olive oil101 are great sources of fats that have been shown to be anti-inflammatory. These contain more of the Omega-3 fats that can balance inflammation as we learnt about in the chapter on heart health (here). I tend to use olive oil liberally in cooking and I use the highest quality, cold-pressed varieties where possible for flavour as well as function.

+ Polyphenols These are a category of health-promoting chemicals that we find in food and there are literally thousands of them. In general, the coloured vegetables lining our supermarket grocery aisles are great sources of these potent compounds that can target processes related to inflammation. These targets have long and confusing names like the protein complex ‘nuclear factor kappa B (NF)-κB’102,103 and the enzyme ‘cyclooxygenase (COX)’104, which also happen to be molecular targets for medications that we prescribe for things like arthritis and pain. This isn’t to suggest that we can or should replace drugs with food, but the polyphenols you find in a crisp apple, humble pea or vibrant butternut squash all possess the ability to modulate inflammation by impacting these and many other processes involved in inflammation.105, 106 A rainbow diet is the easiest way to guarantee a collection of polyphenols that can lower the inflammatory burden.103

+ Green foods Of particular mention are undoubtedly the greens. The impact of brassica vegetables including broccoli, rocket, kale, bok choy and sprouts are absolutely incredible, which is why I try to eat these daily, if not at most mealtimes … and yes, that includes breakfast (try my One-pan Greek Breakfast here or Watercress, Walnut and Crayfish here). These ingredients contain many chemicals, including some well-studied compounds called sulforaphane and indole-3-carbinole that prevent oxidative stress.107,108 These are some of the most technologically advanced ‘drugs’ and they’re only available in grocery stores. Get them on your plate.

+ Red foods Deep red-coloured foods contain a particular type of flavonoid called anthocyanin that is well known to be a potent anti-inflammatory chemical.109 We get these from cheap accessible ingredients such as red cabbage, blue- and red-coloured berries, chard as well as more exotic ingredients such as black rice, red carrots and purple potatoes. The benefits of red foods are complemented by other colours in your diet. I am by no means suggesting only eating red and green foods for inflammation, but discovering how and why these foods reduce oxidative stress and balance inflammation is exciting enough for me to include these in my diet regularly.

+ High-fibre foods Higher glycaemic index (high GI) foods that release sugar into the bloodstream rapidly are associated with greater inflammation measures in the blood.110, 111 Regular consumption of these high GI foods, such as refined cereals and grains, breads, pasta, cakes and biscuits (no matter whether they are labelled ‘healthy’, ‘wholegrain’, ‘gluten free’, or anything else that has an apparent health connotation) is associated with a higher inflammatory burden. This is not a call to remove these foods entirely from your diet. I would never want to rob someone the pleasure of enjoying delicious freshly prepared pasta or a warm, fluffy doughnut with sticky jam. But, greater awareness of why these are not the best foods to eat regularly will mould your daily choices and heighten your understanding of what health-promoting food means for you. A simple way to reduce inflammation is simply switching from carbohydrates that quickly release sugar into the blood to foods that are higher in fibre and thus release sugar more slowly.112 Examples include split peas, artichokes, onions, whole apples, black beans and yellow lentils. In addition, these foods positively enhance the population of gut microbes by giving them a food source to flourish on.

+ Spices Exotic spices, such as turmeric and cloves, have become a popular topic among those trying to lead a healthier lifestyle. While I welcome greater research into the exciting compounds found within these spices, especially as they may have a role in treatment of inflammatory disorders such as osteoarthritis, psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis,113, 114, 115 they are by no means the only ones. As a general rule of thumb, a wide range of spices contain dense concentrations of phytochemicals and micronutrients, which provide a variety of antioxidants that have the potential to reduce inflammation.116, 117 Rather than concentrating your diet around specific spices that you may not even enjoy or have access to, a simple strategy is to use those that you appreciate the flavour of. You’ll notice all of my dishes use plenty of spices and herbs and there is a clinical as well as culinary reason behind this. I’ve purposely included a section dedicated to making fresh pastes and spice blends from scratch (here) and I hope they will encourage you to enjoy the process of using these amazing ingredients, ranging from mint, basil and marjoram to sumac, cinnamon and cayenne.

LIFESTYLE 360

These changes to the diet can serve to improve our balance from a state of pro-inflammation to one that is more harmonious with the intended function of our bodies. Your lifestyle, however, is important and these practices are just as impactful.

+ Slow down your eating I used to find myself running from appointments across the city with a snack in my hand, eating at my desk to sift through mounting paperwork during clinic or squeezing meals into a 10-minute break on an A&E shift. Many of my colleagues and patients relate to this. Even when we’re not rushed, we eat in front of screens, we scoff food at pace and hardly ever take time to appreciate the ingredients themselves. A measurement of stress in the body is a hormone called cortisol that is shown to be lowered if food is eaten slower and more mindfully.118 The state in which food is consumed can be just as impactful on the body as the food itself. As a simple practice, I recommend patients take a few gentle breaths before starting to eat, and remove screens, in an effort to slow down the process so they can give their full attention to the food and perhaps the conversation around them.

+ Mind–body interventions Mind–body interventions, like Tai Chi and meditation, have been shown to reduce the expression of genes which code for proteins that lead to inflammation.119 In many studies, different types of stress-relieving and relaxation techniques have demonstrated significant anti-inflammatory effects.120 There should be no doubt that stress and psychological ill health are associated with inflammation and, conversely, stress-relieving techniques are anti-inflammatory.121 When appropriate I discuss these studies with patients and I find that describing the clinical research underpinning my belief in the utility of mind–body interventions is really motivating for them. Think of mind–body interventions as any practice that encourages inner calm, whether that be the simple act of reading in a quiet space or meditation and yoga practices.

+ Walking If the thought of joining a yoga class or even deep breathing is too overwhelming, you’ll be pleased to hear about the mountains of research that consider the effectiveness of simple walks in nature. The Japanese practice of ‘shinrin yoku’, which literally translates as ‘forest bathing’, has a large body of evidence examining the physiological as well as mental health benefits of this practice.122, 123 Along with a reduction in heart rate, blood pressure and improvements in mood, forest bathing practices have reduced laboratory measures of inflammation such as cortisol and inflammatory proteins measured in the blood. Taking yourself to a park or forest at least once a week for a relaxing stroll could be one of the most hassle-free and effective ways to reduce your inflammatory burden without having to adjust your diet or do much at all.

‘If we can harness the incredible effects of not only our food, but the anti-inflammatory potential of our lifestyle, we could drastically reduce the problems that excess inflammation poses to our health.’

+ Sleep Given the number of homeostatic mechanisms that occur during sleep, it’s unsurprising that even a single night’s lack of shut-eye increases inflammatory signals in the body.124 During sleep our blood pressure lowers, our temperature drops and levels of rejuvenating hormones like melatonin, which have powerful antioxidant effects, rise to their highest levels. As told in exceptionally certain terms in his book Why We Sleep, the sleep medicine expert Professor Walker has warned that a lack of sleep puts us at greater risk of diabetes, cancer and cardiovascular disease. It’s often noted that people with high inflammation, as a result of conditions such as arthritis, diabetes or obesity, often have disturbed sleep. It appears that inflammation and the proteins that signal inflammation have an interconnected relationship to sleep and may even regulate our need for slumber.125 The advice for now is to at least allow yourself the opportunity to enjoy about 8–9 hours of rest per day. Put your electronic devices away a couple of hours before bed, eat early if possible and give yourself potentially the best dose of anti-inflammatory medication available to us.