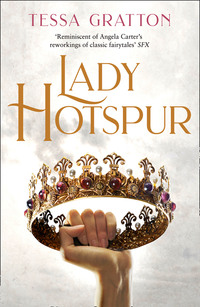

Lady Hotspur

Even Lady Ianta Oldcastle had gone—drinking herself stupid in her leaning town house down by the docks. Every day since word had come of Rovassos’s death.

Alone, Mora would not weep; she would not tremble. She was a daughter of Aremoria and of Innis Lear and of the Third Kingdom. Three strong bloodlines united.

“I am Banna Mora of the March,” she murmured to herself again, and left it at that.

When the door opened it was not Hal Bolinbroke who entered: it was a woman in worn leather and steel armor, walking hard in war boots, a pine-green cape pinned over her oyster-shell pauldrons. Red hair braided in a crown was incongruously set with small blue flowers.

Lady Hotspur grinned and strode across the marble floor. “Mora,” she said, voice light for such a compact figure.

Mora could not return the smile, though she liked Hotspur Persy well enough. She’d witnessed the famous baiting of that Burgundian earl last year, at the Persy Tournament, and had shared a hearty meal and heartier laughter with the soldier.

But Hotspur had helped depose Rovassos, and she was here to take Mora’s title.

And behind the Wolf of Aremoria came Hal.

Prince Hal, Mora supposed, feeling the cold drain of uncertainty hardening her expression as she met Hal’s rich brown eyes.

“I knew you’d be here,” Hal said. “Didn’t I, Hotspur.”

Hal was in orange and Bolinbroke purple, both of which suited her creamy complexion and her stark black hair. Unlike Hotspur, Hal had no armor, only a fine jacket with a full skirt that split and flared behind her. And all that hair was loose, falling around her face and shoulders in messy waves. Her gaze fell to the sword at Mora’s hip.

But Hotspur stared at Prince Mars, lips parted. “I’ve never seen this one,” she murmured.

Hal flung an arm around Hotspur’s shoulders. “It’s the best. The only one in Lionis where he’s not got a beard.”

“Nothing wrong with a beard.” Hotspur laughed.

The new prince’s face fell as she studied the portrait behind Mora, as if she, too, were seeing a ghost.

Mora remained still, her gaze flicking between the two of them: Hotspur staid and practical, stance wide and ready for attack, but not shifting away from Hal’s embrace in the slightest; Hal’s fingers pressing slightly too hard into Hotspur’s pauldron so that the tips blanched and her nails turned pink.

Like Mora, Hal was tall, and when the new prince glanced at her, their eyes locked. “Mother will be in the throne room, and Abovax promised to knock on the wall and let me know they are ready for you.”

“What does she want from me?”

Hotspur lifted an incredulous eyebrow. “Surrender! A vow of honest loyalty. Banna Mora, you have to go through the formality. It is war, and rules of war will be observed.”

“War?” Anger sparked against Mora’s teeth when she bared them. But she smoothed her features again before continuing. “War is between kings; this was a coup. This was an illegal seizure of power. You won, but it was not war.”

“Soldiers died killing each other under orders from their commanders; that is war,” Hotspur said firmly. “You’re talking about politics.”

“Maybe.” Mora looked again at Hal, whose cheeks were actually too pale, the edges of her lips white. “I know Celeda has taken the Blood and the Sea, and I know my uncle is dead, but tell me the rest before I appear for her.”

Hal let go of Hotspur. It was a bad sign, but still Mora was surprised when she said, “Vin and Dev both, Mora. I’m sorry. There’s more, but …”

Clenching her hands tighter together, Mora pushed it all down. She could grieve later, tear something apart later, scream later. “How?” she whispered.

“Vin in the heat of battle—”

“On your side,” Mora interrupted.

Hal only hesitated a moment before she nodded.

“There was no other side,” Hotspur said, with surprising gentleness.

Mora turned away from them completely.

“I always wanted to join your knights,” Hotspur added. “I was needed in Perseria, but the stories I heard of Banna Mora’s Lady Knights, of you and Hal, your adventures—I wished to be here. It sounded glorious.”

“It still can be,” Hal said. “Mora, don’t think now, don’t react, only come with us and tell my mother what she needs to hear, and stay. Be a knight. Be—mine. You’ll be a royal knight still.”

As if Prince Mars lived and watched from the portrait, judging her, as if the funeral fires painted into the background burned for Mora’s death, Mora could only breathe thinly. In order to survive, she had to accept. She knew it. She hated it.

Hal continued, though. “Hotspur has agreed to be my second. My commander. I need one, to be a prince, to build my own court. And I need someone to tell me how to do it all. An advisor. You.”

“I want the March.”

“Yes, I think Mother will agree to that.”

Mora turned, and under her glare, Hal said, “I’ll make sure Mother agrees to that. Banna Mora of the March, still and always.”

It was so difficult for Mora to speak. She refused to allow her mind to wander away from this precise moment to Vindus, dead, or the true Blood and the Sea pressed beneath her bodice.

Hal touched Mora’s face. Clasped it in both hands, so Mora could not pull away. She said, “Banna Mora, on my knee in that throne room beyond, I promised to serve you, and I swear still to keep that vow by keeping you thriving, at my side. I need you, and even so, I think you might reject me, and all of this, and leave. But I have loved you since I was ten years old, and we have been friends—sisters, even. Please try with me. Try to change with our changing world. You can do that, because you can do anything.”

Such a pretty story. Hal was so good at making everything into a pretty story. Tears pinched Mora’s eyes. “Did you practice that?” she spat, but could not keep either her despair or her cursed fondness out of her voice.

“She did,” Hotspur said. “I thought it was good.”

“Hotspur is enamored with me,” Hal whispered.

Hotspur gasped. “I am—I am not!”

Now Mora opened her eyes in time to see the heat in Hal’s gaze when she watched Hotspur Persy splutter. Mora saw, and read it clearly: Hal was the one besotted.

Mora said, “Who would not be,” though a mean part of her reveled. While Hal had been merely a knight almost none had given any care to whom she fucked. But now—now it would be a matter of state.

Hal’s hands loosened against Mora’s face, her grip becoming a soft caress. “Will you go with me, my friend?”

With hands that did not shake, Mora unsheathed her sword, stepping back.

Hotspur sucked in a quick breath, but Hal did not move. She kept her eyes on Mora’s face.

It was the Heir’s Score. A sword of dark Errigal steel—forged on Innis Lear, with the power of iron wizards, never to break. The grip was wrapped with black leather, the crosspiece short and set with a single pearl. Through the heavy silence, Mora flipped it and offered the hilt to Hal. “Yes, Hal Bolinbroke, I will go with you. But you are friend no longer; our prince instead.”

“Both,” Hal insisted.

But of the two of them, Mora had the experience with the heavy crown, and she did not think both was possible anymore.

HOTSPUR

Lionis, early summer

THERE WERE MANY ways to make a queen:

On Innis Lear it was a bargain between the crown and the wind and the trees: to rule, a queen must eat of the starweed and drink of the rootwater; the one would kill her, the other save her. If that was her destiny.

For a hundred years it had been so, since Elia the Dreamer was reborn in a pool of starlight. Her daughter Gaela was made queen in perfect peace, surrounded by loved ones as she processed to the ancient navel well at the edge of the Tarinnish, that deep black lake called the Well of Lear; the next queen Astora was made in grief that she was not ready to take up the poison crown, torn apart by loss and hope, wishing to put a sister or cousin in her place.

The current queen of Innis Lear was made when only thirteen. Everyone knew the story, even in Aremoria: her mother died suddenly, and tradition held that young Solas rule in name only, under the auspices of her uncle or father. Many were in favor of such an arrangement, but Solas did not care which men argued and which supported her—not then, at least, though she would remember well and plan accordingly later. She said only, “Let the island have its argument.” It was always a queen’s prerogative to listen to the wind and roots, and so rootwaters were brought from a holy well and a flourish of white-blossoming hemlock. The girl crushed the flowers in her hand and licked clean her palm, then scattered the remaining flowers around her feet in a constellation of tiny white petals. She sat suddenly, numbness spreading from her core, and a priest fetched the bowl of rootwater to her. It trickled across her lips and down her chin, but some, too, carried itself down her gullet.

Her heartbeat slowed, and Solas saw blurry stars dancing; they shot from the sky and fell, three of them in a blaze of red-hot light. One growled, one roared, one breathed fire.

When the vision faded, she blinked and stood. Solas put on the crown and calmly pushed her way to the throne. Though barely yet a woman, she said, “I am as much as I shall ever be, and what I am is the queen of Innis Lear.”

Thirty years now she’d ruled, and well.

On Aremoria they rarely had queens at all. It was kings who were made—in blood, in war, in betrayal or illness or simply the gentle passing of a ring.

Celeda Bolinbroke, new monarch of Aremoria by right of successful rebellion, intended to make herself a queen, in the eyes of her people, with a tournament.

Hotspur of Perseria did not approve of tournaments. They were outrageously expensive and served little purpose but ostentation. Tourney did not mirror true warfare, despite the appearance of violence and the use of war weapons and armor. If war itself was a storm, then the tourney was the bardic description of that storm: affecting, and perhaps one might learn something of survival, but it could never prepare one for the power of blasting wind or sharp cutting rain.

She did understand that this tournament was intended for another purpose: consolidating Celeda Bolinbroke’s rule and reminding the country from which she’d been banished for ten long years exactly who she was and the queen she intended to be.

Rovassos’s magnificent pageantries had been known across Aremoria, as well as its surrounding lands, for their wonderful food and entertainments, and the epic melee at their heart. The king had sponsored one annually in the early spring, boasting the year long that his last had been the grandest of all, that the clowns had been riveting, the warriors strong, the stilt-walkers airy as ghosts; three knights nearly died in the melee, you know, and guests had come from as far away as the Third Kingdom, but naturally the awards for best bravery had gone to knights Aremore born and bred.

Wisely, Celedrix did not intend to compete in splendor with the memory of her deposed uncle’s tournaments. Hers would be a celebration, yes, of summertime, of renewal and rebirth, with mummers and clowns, the traditional presentation of colors, and newly commissioned plays celebrating the queen’s courage and triumphant return from the Third Kingdom. There would still be a melee (Hotspur had been commissioned to lead one team of knights against Corio de Or commanding the other), followed the next day by a single-combat roundtable competition. It was the roundtable the audience looked most forward to, for the opportunity to champion their favorites, place wagers, and bestow favors. The champions’ feast on the final night would bring honor to the winners by seating them with the queen, where they might be granted titles or lands, or choose squires for themselves. The food would be magnificent, the fireworks enough to blind the moon, the lovemaking abound—even maybe a marriage or two with the queen and her nobility present to witness.

The difference with which Celedrix prepared to set her tournament most vividly apart from Rovassos’s was simple: Celeda herself would compete in the roundtable.

It was bold, and that Hotspur approved of.

The melee had gone well. Hotspur defeated Corio by breaking through his first aide’s defense and catching the flag off the back of his horse. She’d managed not to kill anyone, too, and she and Corio had celebrated the fact that their melee included no casualties—the crowd might be bloodthirsty, but Hotspur and her mentor disliked wasting men.

Prince Hal told her it wasn’t a waste if their injuries served to bolster the queen’s strength, but Hotspur flicked wine in her face for such a comment.

Today was the roundtable combat. All morning the squires had participated in their own, under the careful eyes of their knights, parents, and some lords who had dragged themselves out of bed early enough after last night’s revelry. Any money won here was too negligible to draw the heaviest bettors, and what the squires earned went directly into the purses of their mentors.

The queen had watched from the royal box, a pavilion decorated in orange and brilliant white.

Now the box was empty but for white-draped chairs and sun-warmed ewers of water. The queen stood near Hotspur in battle regalia. Of thirty-eight participants from across Aremoria, only seven were women, including Celeda, Hotspur, Hal, and Banna Mora. Vindomata of Mercia was not here; she had remained at home with her husband, refusing to celebrate the success of her own rebellion, given the loss of her sons. This was hard for Hotspur, too, without hilarious, angry Vindus or his dour little brother, Dev, urging her on. Cousins, they’d trained together as children, spent winters rampaging across the snowy Perseria forests together. But everyone had lost someone, or something, and Vindomata’s absence made Hotspur uneasy. Already called the King-Killer, she should have been here to prove her friendship with Celedrix.

There would be five rounds of competition: first a joust to cut the number of participants down to sixteen. The remaining four rounds would be sword and buckler, then only sword. Hotspur hardly worried over the joust, and after winning her first round she found Prince Hal beside the royal box. The prince leaned her elbows against the temporary rail and pointed toward the far end of the field where the next combatants prepared: Banna Mora stood beside an armored horse, checking the girth. The former prince gleamed in a beautiful filigreed cuirass fitted to her shape perfectly. Steel faulds layered over her hips almost like a skirt, exaggerating her rear and thick waist. Her gauntlets flashed as she lifted her arms to pull a hood over her tightly braided brown hair.

“There’s a helmet she ought to be wearing that matches the rest of the armor,” Hal said wistfully. “With a thin circlet of copper about the top to imply her title. Though she always was recognizable.”

“You know why she isn’t wearing it.” Hotspur leaned beside Hal, letting their shoulders touch inasmuch as it was possible, with both of them in mail and gambesons. She glanced at the prince, who smiled back without her lips, only with those impossibly bright brown eyes, asking Hotspur for something she did not yet know how to give. But she wanted to. “You should have better armor,” Hotspur said, judging the worn chest plate that clung to Hal’s mail shirt. “Is that …” Hotspur lifted Hal’s arm to goggle at the rigged extra buckle fitting the plate in place. “Surely you can afford armor that fits you, Prince!”

Hal shrugged and took Hotspur’s hand, tugging their arms down. “I lent my armor to my squire Nova; she’s looking to impress today, and I’m not. This is about my mother.”

The skin of Hotspur’s palm tingled against Hal’s, and she felt it in other places, too, places extremely unsuited for public. She jutted out her chin. “Is this modesty false or true?”

“Which would charm you better?”

Hotspur’s lips parted. “The truth,” she murmured.

“Both, then,” Hal said. “It’s true, in that all my actions today should prop up my mother, and false in that I am still playing a game, for to be seen as modest and humble will add to my reputation.”

Pulling her hand free, Hotspur rolled her eyes and turned to watch Lady Ter Melia unseat Sir Gevrus. The two went a round on their feet with swords, and Gevrus fell again. Then Banna Mora mounted against a knight Hotspur did not know and gloriously defeated him with a single strike.

All the Lady Knights and the queen moved on to round two. Hal winked at Hotspur. “Think we’ll face each other before the end?”

Hotspur hoped so, but she shrugged. “I’ll win against whomever I face.”

But the lottery put Prince Hal against her mother in the second round.

The queen and Hal walked out in near unison, but then Hal broke it by waving wildly to the crowd. Purple and orange flags snapped as the people flailed and cheered—this was exactly the sort of match they wished to see.

Celeda seemed everything a queen should be in her dark orange-and-silver armor, and with her naked sword blade-down against her chest she bowed very slightly to her daughter. Hal grinned, red lips parted over her teeth. She said something that made her mother laugh, then Celeda nodded her chin at Hal’s disheveled state. Black hair spilled in messy loops out of the mail hood the prince wore, despite most being caught back in a linen cap to keep it from tangling in the chain mail. That rigged chest plate barely shone in the sunlight. But then Hal lifted her sword—it was a plain soldier’s blade, not the Heir’s Score—and swung around to declare to the crowd, “My sword the strength of Aremoria!”

Hotspur could not look away.

She hardly noticed the call to begin; Celeda and Hal circled each other, then suddenly Hal charged, engaging with a great clash of metal.

While the crowd cheered, Hotspur felt locked into the intensity of their combat: the give and take, shoving and striking steel. Celeda was clearly technically superior, and without a turn of bad luck would win eventually. But Hal’s methods were so enthusiastic it was difficult not to admire her. She smiled brilliantly the whole time, making faces of shock or determination when they were called for, and sometimes her mouth moved. At least once Celeda obviously choked back a laugh. The teasing or jokes or whatever it was Hal threw at her mother did not distract the queen, though.

The bout lasted only a few minutes, but it was longer than most. Celeda got through Hal’s slowing defense and slammed the edge of her shield into the vulnerable crease between Hal’s too-small chest plate and pauldron—where a rondel might’ve protected her. If Celeda had used the blade, it might’ve been a killing stroke. Hal swayed, turning to use the momentum, but her mother was ready for that, too, and used her heavily armored boot to shove Hal to her knees.

Hal dropped her sword and raised her hands in a flourish of surrender. She called out something to the queen, voice hoarse, and the queen laughed. The lord judge yelled the end of the match and summoned a page to dash onto the dusty field with a water sack. This the page offered the queen first; she sipped, then hauled Hal to her feet to share.

With her loss, Hal graciously offered to host from the royal box. The queen granted Prince Hal the right, and so Hal dropped her armor with an aide and climbed triumphantly onto the pavilion. There she sprawled on the throne—the throne!—and poured herself wine before any of the scrambling footmen could.

Hotspur thought she was magnificent.

Two young men sparred next, and then Hotspur’s name was called; she faced an old knight belonging to the Iork family from western Aremoria, and won. Banna Mora won her next bout, too, but Ter Melia did not. Lady Imena progressed to round three, though there she fell to Commander Abovax.

In the royal pavilion Hal gathered young nobles like ducklings. They drank and Hal occasionally leapt to her feet to toss favors at combatants and cry descriptions of the bouts in legendary terms (she ought to have been a poet). Wagers yelled all around from the benches and bales of hay where the nonroyal audience reclined, changing with the changing winners, with the groans of loss and laughing victories. Hotspur vaguely wished to be in the shade with the prince, and to take a chance grazing her thumb against Hal’s lip by feeding her a piece of apple.

Shock coursed through Hotspur when she caught herself imagining. She couldn’t think of such things with the prince! But no—that was not the source of the shock, and neither would Hotspur lie to herself. There were rumors of Prince Hal’s proclivities: gentle, delicate rumors that danced alongside the open progression of womanly lovers Hal’s mentor, Lady Ianta, had always preferred, staining the circle of Lady Knights in a wash of romance and titillating deviance put mostly to rest by Banna Mora’s own connection to Vindus Persy. And all of it had been a suitable shade of dalliance under Rovassos, the Merry King, who’d not loved women any more than Lady Ianta loved men.

Hotspur knew all of this. She’d never cared.

Neither had she considered ever that any of it might be relevant to herself.

But here she was thinking about stealing a slight touch of her thumb to Prince Hal’s red bottom lip.

Then Banna Mora appeared before her in the ring, dark and strong, and Hotspur came solidly back into herself. This was the third round, composed of only eight knights. The queen had easily powered her way through the knight she met, and now Hotspur faced Mora.

The deposed prince clasped Hotspur’s arm and nodded, determination pressing her lips together. In the sunlight, sweat shone against her rich tan cheeks. Hotspur was half a head shorter, but she was shorter than most of the men, too. She stomped her feet against the dusty, bloody field of combat to feel the solid strength of Aremoria reverberate up her bones.

“A favor!” cried Prince Hal from the royal pavilion.

Both Hotspur and Mora faced the prince. At her side the queen sat in chain mail, straight backed with a goblet of cool watered wine and a girl slowly fanning her. All waited, but for a moment Hal glanced between the two knights as if suddenly stuck on which she should favor. Only Hotspur could hear Mora’s impatient growl.

“Stupid if she gives it to me,” Mora said quietly.

“Or forgiving,” Hotspur murmured back, praying to the earth saints Hal would not come too close to her now. “To say the crown favors and trusts Banna Mora still.”

But Prince Hal vaulted over the box and strode to them. She took Mora’s hand and kissed it, giving Hotspur a temporary relief, but then Hal stepped in close to Hotspur and put her lips to Hotspur’s cheek. Hotspur’s eyes fluttered closed as if she were some maidenly child.

“My favor,” Hal murmured, then spun to face the whole of the audience and said it again much more loudly: “My favor to the Wolf of Aremoria!”

A cheer rose, along with laughter, and Mora said quietly for only the two of them: “Well done, Hal. She’ll win.”

“What!” Hotspur snapped her face toward Mora. But the former prince was watching Hal, who nodded sharply.

“Hotspur,” Hal said, “be a good sport!” Then she shrugged jaggedly, and her mouth tipped into a lopsided grin. She bowed to Hotspur just as a great gust of wind tore across the field. Pennants ruffled angrily and folk grabbed their skirts and caps.

Hal spun toward the royal pavilion.

But Queen Celeda stood tall, flanked by drooping orange banners, her head up and her dark hair perfectly in place. “Even the wind is eager for this combat,” she called.

“Yes!” Hal threw her fist into the air. She dashed off the field, mail flashing. The prince did not climb over the rail into the royal pavilion, just leaned back against it, elbows propped and long legs stretched before her. In her expression was an intensity—nearly longing, but sharper—as she stared at Hotspur.