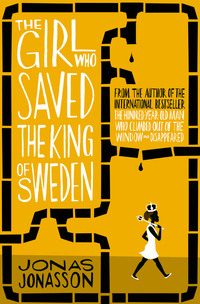

The Girl Who Saved the King of Sweden

Engelbrecht van der Westhuizen shuddered at the memory of what had happened when he ended up with three Chinks in his employ, but these days they were useful to a certain extent – and by all means, perhaps throwing a darky into the mix would liven things up. Even if this particular one, with a broken leg, broken arm and her jaw in pieces might mostly be in the way.

‘At half salary, in that case,’ he said. ‘Just look at her, Your Honour.’ Engineer Engelbrecht van der Westhuizen suggested a salary of five hundred rand per month minus four hundred and twenty rand for room and board. The judge nodded his assent.

Nombeko almost burst out laughing. But only almost, because she hurt all over. What that fat-arse of a judge and liar of an engineer had just suggested was that she work for free for the engineer for more than seven years. This, instead of paying a fine that would hardly add up to a measurable fraction of her collected wealth, no matter how absurdly large and unreasonable it was.

But perhaps this arrangement was the solution to Nombeko’s dilemma. She could move in with the engineer, let her wounds heal and run away on the day she felt that the National Library in Pretoria could no longer wait. After all, she was about to be sentenced to domestic service, not prison.

She was considering accepting the judge’s suggestion, but she bought herself a few extra seconds to think by arguing a little bit, despite her aching jaw: ‘That would mean eighty rand per month net pay. I would have to work for the engineer for seven years, three months and twenty days in order to pay it all back. Your Honour, don’t you think that’s a rather harsh sentence for a person who happened to get run over on a pavement by someone who shouldn’t even have been driving on the street, given his alcohol intake?’

The judge was completely taken aback. It wasn’t just that the girl had expressed herself. And expressed herself well. And called the engineer’s sworn description of events into question. She had also calculated the extent of the sentence before anyone else in the room had been close to doing so. He ought to chastise the girl, but . . . he was too curious to know whether her calculations were correct. So he turned to the court aide, who confirmed, after a few minutes, that ‘Indeed, it looks like we’re talking about – as we heard – seven years, three months, and . . . yes . . . about twenty days or so.’

Engelbrecht van der Westhuizen took a gulp from the small brown bottle of cough medicine he always had with him in situations where one couldn’t simply drink brandy. He explained this gulp by saying that the shock of the horrible accident must have exacerbated his asthma.

But the medicine did him good: ‘I think we’ll round down,’ he said. ‘Exactly seven years will do. And anyway, the dents on the car can be hammered out.’

Nombeko decided that a few weeks or so with this Westhuizen was better than thirty years in prison. Yes, it was too bad that the library would have to wait, but it was a very long walk there, and most people would prefer not to undertake such a journey with a broken leg. Not to mention all the rest. Including the blister that had formed as a result of the first sixteen miles.

In other words, a little break couldn’t hurt, assuming the engineer didn’t run her over a second time.

‘Thanks, that’s generous of you, Engineer van der Westhuizen,’ she said, thereby accepting the judge’s decision.

‘Engineer van der Westhuizen’ would have to do. She had no intention of calling him ‘baas.’

* * *

Immediately following the trial, Nombeko ended up in the passenger seat beside Engineer van der Westhuizen, who headed north, driving with one hand while swigging a bottle of Klipdrift brandy with the other. The brandy was identical in odour and colour to the cough medicine Nombeko had seen him drain during the trial.

This took place on 16 June 1976.

On the same day, a bunch of school-aged adolescents in Soweto got tired of the government’s latest idea: that their already inferior education should henceforth be conducted in Afrikaans. So the students went out into the streets to air their disapproval. They were of the opinion that it was easier to learn something when one understood what one’s instructor was saying. And that a text was more accessible to the reader if one could interpret the text in question. Therefore – said the students – their education should continue to be conducted in English.

The surrounding police listened with interest to the youths’ reasoning, and then they argued the government’s point in that special manner of the South African authorities.

By opening fire.

Straight into the crowd of demonstrators.

Twenty-three demonstrators died more or less instantly. The next day, the police advanced their argument with helicopters and tanks. Before the dust had settled, another hundred human lives had been extinguished. The City of Johannesburg’s department of education was therefore able to adjust Soweto’s budgetary allocations downward, citing lack of students.

Nombeko avoided experiencing any of this. She had been enslaved by the state and was in a car on the way to her new master’s house.

‘Is it much farther, Mr Engineer?’ she asked, mostly to have something to say.

‘No, not really,’ said Engineer van der Westhuizen. ‘But you shouldn’t speak out of turn. Speaking when you are spoken to will be sufficient.’

Engineer Westhuizen was a lot of things. The fact that he was a liar had become clear to Nombeko back in the courtroom. That he was an alcoholic became clear in the car after leaving the courtroom. In addition, he was a fraud when it came to his profession. He didn’t understand his own work, but he kept himself at the top by telling lies and exploiting people who did understand it.

This might have been an aside to the whole story if only the engineer hadn’t had one of the most secret and dramatic tasks in the world. He was the man who would make South Africa a nuclear weapons nation. It was all being orchestrated from the research facility of Pelindaba, about an hour north of Johannesburg.

Nombeko, of course, knew nothing of this, but her first inkling that things were a bit more complicated than she had originally thought came as they approached the engineer’s office.

Just as the Klipdrift ran out, she and the engineer arrived at the facility’s outer perimeter. After showing identification they were allowed to enter the gates, passing a ten-foot, twelve-thousand-volt fence. Next there was a fifty-foot stretch that was controlled by double guards with dogs before it was time for the inner perimeter and the next ten-foot fence with the same number of volts. In addition, someone had thought to place a minefield around the entire facility, in the space between the ten-foot fences.

‘This is where you will atone for your crime,’ said the engineer. ‘And this is where you will live, so you don’t take off.’

Electric fences, guards with dogs and minefields were variables Nombeko hadn’t taken into account in the courtroom a few hours earlier.

‘Looks cosy,’ she said.

‘You’re talking out of turn again,’ said the engineer.

* * *

The South African nuclear weapons programme was begun in 1975, the year before a drunk Engineer van der Westhuizen happened to run over a black girl. There were two reasons he had been sitting at the Hilton Hotel and tossing back brandies until he was gently asked to leave. One was that part about being an alcoholic. The engineer needed at least a full bottle of Klipdrift per day to keep the works going. The other was his bad mood. And his frustration. The engineer had just been pressured by Prime Minister Vorster, who complained that no progress had been made yet even though a year had gone by.

The engineer tried to maintain otherwise. On the business front, they had begun the work exchange with Israel. Sure, this had been initiated by the prime minister himself, but in any case uranium was heading in the direction of Jerusalem, while they had received tritium in return. There were even two Israeli agents permanently stationed at Pelindaba for the sake of the project.

No, the prime minister had no complaints about their collaboration with Israel, Taiwan and others. It was the work itself that was limping along. Or, as the prime minister put it:

‘Don’t give us a bunch of excuses for one thing and the next. Don’t give us any more teamwork right and left. Give us an atomic bomb, for fuck’s sake, Mr van der Westhuizen. And then give us five more.’

* * *

While Nombeko settled in behind Pelindaba’s double fence, Prime Minister Balthazar Johannes Vorster was sitting in his palace and sighing. He was very busy from early in the morning to late at night. The most pressing matter on his desk right now was that of the six atomic bombs. What if that obsequious Westhuizen wasn’t the right man for the job? He talked and talked, but he never delivered.

Vorster muttered to himself about the damn UN, the Communists in Angola, the Soviets and Cuba sending hordes of revolutionaries to southern Africa, and the Marxists who had already taken over in Mozambique. Plus those CIA bastards who always managed to figure out what was going on, and then couldn’t shut up about what they knew.

Oh, fuck it, thought B. J. Vorster about the world in general.

The nation was under threat now, not once the engineer chose to take his thumb out of his arse.

The prime minister had taken the scenic route to his position. In the late 1930s, as a young man, he had become interested in Nazism. Vorster thought that the German Nazis had interesting methods when it came to separating one sort of people from the next. He also liked to pass this on to anyone who would listen.

Then a world war broke out. Unfortunately for Vorster, South Africa took the side of the Allies (it being part of the British Empire), and Nazis like Vorster were locked up for a few years until the war had been won. Once he was free again, he was more cautious; neither before nor since have Nazi ideals gained ground by being called what they actually are.

By the 1950s, Vorster was considered to be housebroken. In 1961, the same year that Nombeko was born in a shack in Soweto, he was promoted to the position of minister of justice. One year later, he and his police managed to reel in the biggest fish of all – the African National Congress terrorist Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela.

Mandela received a life sentence, of course, and was sent to an island prison outside Cape Town, where he could sit until he rotted away. Vorster thought it might go rather quickly.

While Mandela commenced his anticipated rotting-away, Vorster himself continued to climb the ladder of his career. He had some help with the last crucial step when an African with a very specific problem finally cracked. The man had been classed as white by the system of apartheid, but it was possible they had been wrong, because he looked more black – and therefore he didn’t fit in anywhere. The solution to the man’s inner torment turned out to be finding B. J. Vorster’s predecessor and stabbing him in the stomach with a knife – fifteen times.

The man who was both white and something else was locked up in a psychiatric clinic, where he sat for thirty-three years without ever finding out which race he belonged to.

Only then did he die. Unlike the prime minister with fifteen stab wounds, who, on the one hand, was absolutely certain he was white but, on the other hand, died immediately.

So the country needed a new prime minister. Preferably someone tough. And soon enough, there sat former Nazi Vorster.

When it came to domestic politics, he was content with what he and the nation had achieved. With the new anti-terrorism laws, the government could call anyone a terrorist and lock him or her up for as long as they liked, for any reason they liked. Or for no reason at all.

Another successful project was to create homelands for the various ethnic groups – one country for each sort, except the Xhosa, because there were so many of them that they got two. All they had to do was gather up a certain type of darky, bus them all to a designated homeland, strip them of their South African citizenship, and give them a new one in the name of the homeland. A person who is no longer South African can’t claim to have the rights of a South African. Simple mathematics.

When it came to foreign politics, things were a bit trickier. The world outside continually misunderstood the country’s ambitions. For example, there was an appalling number of complaints because South Africa was operating on the simple truth that a person who is not white will remain that way once and for all.

Former Nazi Vorster got a certain amount of satisfaction from the collaboration with Israel, though. They were Jews, of course, but in many ways they were just as misunderstood as Vorster himself.

Oh, fuck it, B. J. Vorster thought for the second time.

What was that bungler Westhuizen up to?

* * *

Engelbrecht van der Westhuizen was pleased with the new servant Providence had given him. She had managed to get some things done even while limping around with her leg in a brace and her right arm in a sling. Whatever her name was.

At first he had called her ‘Kaffir Two’ to distinguish her from the other black woman at the facility, the one who cleaned in the outer perimeter. But when the bishop of the local Reformed Church learned of this name, the engineer was reprimanded. Blacks deserved more respect than that.

The Church had first allowed blacks to attend the same communion services as whites more than one hundred years ago, even if the former had to wait their turn at the very back until there were so many of them that they might as well have their own churches. The bishop felt that it wasn’t the Church’s fault that the blacks bred like rabbits.

‘Respect,’ he repeated. ‘Think about it, Mr Engineer.’

The bishop did make an impression on Engelbrecht van der Westhuizen, but that didn’t make Nombeko’s name any easier to remember. So when spoken to directly she was called ‘whatsyourname,’ and indirectly . . . there was essentially no reason to discuss her as an individual.

Prime Minister Vorster had come to visit twice already, always with a friendly smile, but the implied message was that if there weren’t six bombs at the facility soon, then Engineer Westhuizen might not be there, either.

Before his first meeting with the prime minister, the engineer had been planning to lock up whatshername in the broom cupboard. Certainly it was not against the rules to have black and coloured help at the facility, as long as they were never granted leave, but the engineer thought it looked dirty.

The drawback to having her in a cupboard, however, was that then she couldn’t be in the vicinity of the engineer, and he had realized early on that it wasn’t such a bad idea to have her nearby. For reasons that were impossible to understand, things were always happening in that girl’s brain. Whatshername was far more impudent than was really permissible, and she broke as many rules as she could. Among the cheekiest things she’d done was to be in the research facility’s library without permission, going so far as to take books with her when she left. The engineer’s first instinct was to put a stop to this and get the security division involved for a closer investigation. What would an illiterate from Soweto want with books?

But then he noticed that she was actually reading what she had brought with her. This made the whole thing even more remarkable – literacy was, of course, not a trait one often found among the country’s illiterate. Then the engineer saw what she was reading, and it was everything, including advanced mathematics, chemistry, electronic engineering and metallurgy (that is, everything the engineer himself should have been brushing up on). On one occasion, when he took her by surprise with her nose in a book instead of scrubbing the floor, he could see that she was smiling at a number of mathematical formulas.

Looking, nodding and smiling.

Truly outrageous. The engineer had never seen the point in studying mathematics. Or anything else. Luckily enough, he had still received top grades at the university to which his father was the foremost donor.

The engineer knew that a person didn’t need to know everything about everything. It was easy to get to the top with good grades and the right father, and by taking serious advantage of other people’s competence. But in order to keep his job this time, the engineer would have to deliver. Well, not literally him, but the researchers and technicians he had made sure to hire and who were currently toiling day and night in his name.

And the team was really moving things forward. The engineer was sure that in the not-too-distant future they would solve the few technical conflicts that remained before the nuclear weapons tests could begin. The research director was no dummy. He was, however, a pain – he insisted on reporting each development that occurred, no matter how small, and he expected a reaction from the engineer each time.

That’s where whatshername came in. By letting her page freely through the books in the library, the engineer had left the mathematical door wide open, and she absorbed everything she could on algebraic, transcendental, imaginary and complex numbers, on Euler’s constant, on differential and Diophantine equations, and on an infinite (∞) number of other complex things, all more or less incomprehensible to the engineer himself.

In time, Nombeko would have come to be called her boss’s right hand, if only she hadn’t been a she and above all hadn’t had the wrong colour skin. Instead she got to keep the vague title ‘help’, but she was the one who (alongside her cleaning) read the research director’s many brick-size tomes describing problems, test results and analyses. That is, what the engineer couldn’t manage to do on his own.

‘What is this crap about?’ Engineer Westhuizen said one day, pressing another pile of papers into his cleaning woman’s hands.

Nombeko read it and returned with the answer.

‘It’s an analysis of the consequences of the static and dynamic overpressure of bombs with different numbers of kilotons.’

‘Tell me in plain language,’ said the engineer.

‘The stronger the bomb is, the more buildings blow up,’ Nombeko clarified.

‘Come on, the average mountain gorilla would know that. Am I completely surrounded by idiots?’ said the engineer, who poured himself a brandy and told his cleaning woman to go away.

* * *

Nombeko thought that Pelindaba, as a prison, was just short of exceptional. She had her own bed, access to a bathroom instead of being responsible for four thousand outhouses, two meals a day and fruit for lunch. And her own library. Or . . . it wasn’t actually her own, but no one besides Nombeko was interested in it. And it wasn’t particularly extensive; it was far from the class she imagined the one in Pretoria to be in. And some of the books on the shelves were old or irrelevant or both. But still.

For these reasons she continued rather cheerfully to serve her time for her poor judgement in allowing herself to be run over on a pavement by a plastered man that winter day in Johannesburg in 1976. What she was experiencing now was in every way better than emptying latrines in the world’s largest human garbage dump.

When enough months had gone by, it was time to start counting years instead. Of course, she gave a thought or two to how she might be able to spirit herself out of Pelindaba prematurely. It would be a challenge as good as any to force her way through the fences, the minefield, the guard dogs and the alarm.

Dig a tunnel?

No, that was such a stupid thought that she dropped it immediately.

Hitchhike?

No, any hitchhiker would be discovered by the guards’ German shepherds, and then all one could do was hope that they went for the throat first so that the rest wasn’t too bad.

Bribery?

Well, maybe . . . but she would have only one chance, and whomever she tried this on would probably take the diamonds and report her, in South African fashion.

Steal someone else’s identity, then?

Yes, that might work. But the hard part would be stealing someone else’s skin colour.

Nombeko decided to take a break from her thoughts of escape. Anyway, it was possible that her only chance would be to make herself invisible and equip herself with wings. Wings alone wouldn’t suffice: she would be shot down by the eight guards in the four towers.

She was just over fifteen when she was locked up within the double fences and the minefield, and she was well on her way to seventeen when the engineer very solemnly informed her that he had arranged a valid South African passport for her, even though she was black. The fact was, without one she could no longer have access to all the corridors that the indolent engineer felt she ought to have access to. The rules had been issued by the South African intelligence agency, and Engineer Westhuizen knew how to pick his battles.

He kept the passport in his desk drawer and, thanks to his incessant need to be domineering, he made lots of noise about how he was forced to keep it locked up.

‘That’s so you won’t get it into your head to run away, whatsyourname. Without a passport you can’t leave the country, and we can always find you, sooner or later,’ said the engineer, giving an ugly grin.

Nombeko replied that it said in the passport whathernamewas, in case the engineer was curious, and she added that he had long since given her the responsibility for his key cabinet. Which included the key to his desk drawer.

‘And I haven’t run away because of it,’ said Nombeko, thinking that it was more the guards, the dogs, the alarm, the minefields and the twelve thousand volts in the fence that kept her there.

The engineer glared at his cleaning woman. She was being impudent again. It was enough to make a person crazy. Especially since she was always right.

That damned creature.

Two hundred and fifty people were working, at various levels, on the most secret of all secret projects. Nombeko could state with certainty early on that the man at the very top lacked talent in every area except feathering his own nest. And he was lucky (up until the day he wasn’t any more).

During one phase of the project development, one of the most difficult problems that needed to be solved was the constant leakage in experiments with uranium hexafluoride. The engineer had a blackboard on the wall of his office upon which he drew lines and made arrows, fumbling his way through formulas and other things to make it appear as if he were thinking. The engineer sat in his easy chair mumbling ‘hydrogen-bearing gas’, ‘uranium hexafluoride’ and ‘leakage’ interspersed with curses in both English and Afrikaans. Perhaps Nombeko should have let him mumble away: she was there to clean. But at last she said, ‘Now, I don’t know much about what a “hydrogen-bearing gas” is, and I’ve hardly even heard of uranium hexafluoride. But I can see from the slightly hard-to-interpret attempts on the wall that you are having an autocatalytic problem.’

The engineer said nothing, but he looked past whatshername at the door into the hallway in order to make sure that no one was standing there and listening, since he was about to be befuddled by this strange being for the umpteenth time in a row.

‘Should I take your silence to mean that I have permission to continue? After all, you usually wish me to answer when I’m spoken to and only then.’

‘Yes, get on with it then!’ said the engineer.

Nombeko gave a friendly smile and said that as far as she was concerned, it didn’t really matter what the different variables were called, it was still possible to do mathematics with them.

‘We’ll call hydrogen-bearing gas A, and uranium hexafluoride can be B,’ Nombeko said.