The Comic Latin Grammar: A new and facetious introduction to the Latin tongue

The vocative case is known by calling, or speaking to; as, O magister – O master; an exclamation which is frequently the consequence of shirking out, making false concords or quantities, obstreperous conduct in school, &c.

The ablative case is known by certain prepositions, expressed or understood; as Deprensus magistro – caught out by the master. Coram rostro– before the beak. The prepositions, in, with, from, by, and the word, than, after the comparative degree, are signs of the ablative case. In angustiâ – in a fix. Cum indigenâ – with a native. Ab arbore – from a tree. A rictu – by a grin. Adipe lubricior – slicker than grease.

GENDERS AND ARTICLES

The genders of nouns, which are three, the masculine, the feminine, and the neuter, are denoted in Latin by articles. We have articles, also, in English, which distinguish the masculine from the feminine, but they are articles of dress; such as petticoats and breeches, mantillas and mackintoshes. But as there are many things in Latin, called masculine and feminine, which are nevertheless not male and female, the articles attached to them are not parts of dress, but parts of speech.

We will now, with our readers’ permission, initiate them into a new mode of declining the article hic, hæc, hoc. And we take this opportunity of protesting against the old and short-sighted system of teaching a boy only one thing at a time, which originated, no doubt, from the general ignorance of everything but the dead languages which prevailed in the monkish ages. We propose to make declensions, conjugations, &c., a vehicle for imparting something more than the mere dry facts of the immediate subject. And if we can occasionally inculcate an original remark, a scientific principle, or a moral aphorism, we shall, of course, think ourselves sufficiently rewarded by the consciousness – et cætera, et cætera, et cætera.

Masc. hic. Fem. hæc. Neut. hoc, &cThe nominative singular’s hic, hæc, and hoc, —Which to learn, has cost school boys full many a knock;The genitive ’s hujus, the dative makes huic,(A fact Mr. Squeers never mentioned to Smike);Then hunc, hanc, and hoc, the accusative makes,The vocative – caret – no very great shakes;The ablative case maketh hôc, hac, and hôc,A cock is a fowl – but a fowl ’s not a cock.The nominative plural is hi, hæ, and hæc,The Roman young ladies were dressed à la Grecque;The genitive case horum, harum, and horum,Silenus and Bacchus were fond of a jorum;The dative in all the three genders is his,At Actium his tip did Mark Antony miss:The accusative ’s hos, has, and hæc in all grammars,Herodotus told some American crammers;The vocative here also – caret – ’s no go,As Milo found rending an oak-tree, you know;And his, like the dative the ablative case is,The Furies had most disagreeable faces.Nouns declined with two articles, are called common. This word common requires explanation – it is not used in the same sense as that in which we say, that quackery is common in medicine, knavery in the law, and humbug everywhere – pigeons at Crockford’s, lame ducks at the Stock Exchange, Jews at the ditto, and Royal ditto, and foreigners in Leicester Square – No; a common noun is one that is both masculine and feminine; in one sense of the word therefore it is uncommon. Parens, a parent, which may be declined both with hic, and hæc, is, for obvious reasons, a noun of this class; and so is fur, a thief; likewise miles, a soldier, which will appear strange to those of our readers, who do not call to mind the existence of the ancient amazons; the dashing white sergeant being the only female soldier known in modern times. Nor have we more than one authenticated instance of a female sailor, if we except the heroine commemorated in the somewhat apocryphal narrative – Billy Taylor.

Nouns are called doubtful when declined with the article hic or hæc – whichever you please, as the showman said of the Duke of Wellington and Napoleon Bonaparte. Anguis, a snake, is a doubtful noun. At all events he is a doubtful customer.

Epicene nouns are those which, though declined with one article only, represent both sexes, as hic passer, a sparrow, hæc aquila, an eagle, – cock and hen. A sparrow, however, to say nothing of an eagle, must appear a doubtful noun with regard to gender, to a cockney sportsman.

After all, there is no rule in the Latin language about gender so comprehensive as that observed in Hampshire, where they call every thing he but a tom-cat, and that she.

DECLENSION OF NOUNS SUBSTANTIVE

There are five declensions of substantives. As a pig is known by his tail, so are declensions of substantives distinguished by the ending of the genitive case. Our fear of outraging the comic feelings of humanity, prevents us from saying quite so much about them as our love of learning would otherwise induce us to do. We therefore refer the student to that clever little book, the Eton Latin Grammar, strongly recommending him to decline the following substantives, by way of an exercise, after the manner of the examples there set down. First declension, Genitivo æ. Virga, a rod. – Second, i. Puer, a boy. Stultus, a fool. Tergum, a back. – Third, is. Vulpes, a fox. Procurator, an attorney. Cliens, a client. – Fourth, ûs – here you may have, Risus, a laugh at. – Fifth, ei. Effigies, an effigy, image, or Guy.

The substantive face, facies, makes faces, facies, in the plural.

Although we are precluded from going through the whole of the declensions, we cannot refrain from proposing “for the use of schools,” a model upon which all substantives may be declined in a mode somewhat more agreeable, if not more instructive, than that heretofore adopted.

Exempli GratiâMusa musæ,The Gods were at tea,Musæ musam.Eating raspberry jam,Musa musâ,Made by Cupid’s mamma,Musæ musarum,Thou “Diva Dearum.”Musis musas,Said Jove to his lass,Musæ musis.Can ambrosia beat this?DECLENSIONS OF NOUNS ADJECTIVE

Some nouns adjective are declined with three terminations – as a pacha of three tails would be, if he were to make a proposal to an English heiress – as bonus, good– tener, tender. Sweet epithets! how forcibly they remind us of young Love and a leg of mutton.

Bonus, bona, bonum,Thou little lambkin dumb,Boni, bonæ, boni,For those sweet chops I sigh,Bono, bonæ, bono,Have pity on my woe,Bonum, bonam, bonum,Thou speak’st though thou art mum,Bone, bona, bonum,“O come and eat me, come,”Bono, bonæ, bono,The butcher lays thee low,Boni, bonæ, bona,Those chops are a picture, – ah!Bonorum, bonarum, bonorum,To put lots of Tomata sauce o’er ’emBonis – Don’t, miss,Bonos, bonas, bona,Thou art sweeter than thy mamma,Boni, bonæ, bona,And fatter than thy papa.Bonis, – What bliss!In like manner decline tener, tenera, tenerum.

Unus, one; solus, alone; totus, the whole; nullus, none; alter, the other; uter, whether of the two – make the genitive case singular in ius and the dative in i.

RIDDLESQ. In what case will a grain of barley joined to an adjective stand for the name of an animal?

A. In the dative case of unus – uni-corn.

Uni nimirum tibi rectè semper erunt res.

Hor. Sat. lib. ii. 2. 106.

Q. Why is the above verse like all nature?

A. Because it is an uni-verse.

The word alius, another, is declined like the above-named adjectives, except that it makes aliud, not alium, in the neuter singular.

The difference of unus from alius, say the London commentators, like that of a humming-top from a peg-top, consists of the ’um.

N.B. Tu es unus alius, is not good Latin for “You’re another,” a phrase more elegantly expressed by “Tu quoque.”

There are some adjectives that remind us of lawyer’s clerks, and, by courtesy, of linen-drapers’ apprentices. These may be termed articled adjectives; being declined with the articles hic, hæc, hoc, after the third declension of substantives – as tristis, sad, melior, better, felix, happy.

It is not very easy to conceive any thing in which sadness and comicality are united, except Tristis Amator, a sad lover.

Melior is not better for comic purposes. Felix affords no room for a happy joke.

Decline these three adjectives, and others of the same class, according to the following rules:

If the nominative endeth in is or er, why, sir,The ablative singular endeth in i, sir;The first, fourth, and fifth case, their neuter make e,But the same in the plural in ia must be.E, or i, are the ablative’s ends, – mark my song,While or to the nominative case doth belong;For the neuter aforesaid we settle it thus:The plural is ora; the singular us.If than is, er, and or, it hath many more enders,The nominative serves to express the three genders;But the plural for ia hath icia and itia,As Felix, felicia – Dives, divitia.COMPARISONS OF ADJECTIVES

Comparisons are odious —

Adjectives have three degrees of comparison. This is perhaps the reason why they are so disagreeable to learn.

The first degree of comparison is the positive, which denotes the quality of a thing absolutely. Thus, the Eton Latin Grammar is lepidus, funny.

The second is the comparative, which increases or lessens the quality, formed by adding or to the first case of the positive ending in i. Thus the Charter House Grammar, is lepidor – funnier, or more funny. – The third is the superlative, which increases or diminishes the signification to the greatest degree, formed from the same case by adding thereto, ssimus. Thus the Comic Latin Grammar is lepidissimus, funniest, or most funny. A Londoner is acutus, sharp, or ’cute, – a Yorkshireman acutior, sharper, or more sharp, ’cuter or more ’cute – but a Yankee is acutissimus – sharpest, or most sharp, ’cutest or most ’cute, or tarnation ’cute.

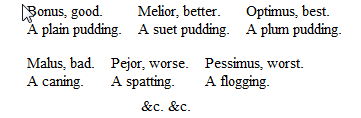

Enumerate, in the manner following, with substantives, the exceptions to this rule, mentioned in the Eton Grammar.

Adjectives ending in er, form the superlative in errimus. The taste of vinegar is acer, sour; that of verjuice acrior, more sour; the visage of a tee-totaller, acerrimus, sourest, or most sour.

Agilis, docilis, gracilis, facilis, humilis, similis, change is into llimus, in the superlative degree.

Agilis, nimble. – Madlle. Taglioni.

Agilior, more nimble. – Jim Crow.

Agillimus, most nimble. – Mr. Wieland.

Docilis, docile. – Learned Pig.

Docilior, more docile. – Ourang-outang.

Docillimus, most docile. – Man Friday.

Gracilis, slender. – A whipping post.

Gracilior, more slender. – A fashionable waist.

Gracillimus, most slender. – A dustman’s leg.

&c. &c.

If a vowel comes before us in the nominative case of an adjective, the comparison is made by magis, more, and maximè, most.

Pius, pious. – Dr. Cantwell.

Magis pius, more pious. – Mr. Maw-worm.

Maximè pius, most pious. – Mr. Stiggins.

Sancho Panza called Don Quixote, Quixottissimus. This was not good Latin, but it evinced a knowledge on Sancho’s part, of the nature of the superlative degree.

OF A PRONOUN

A pronoun is a substitute, or (as we once heard a lady of the Malaprop family say), a subterfuge for a noun.

There are fifteen Pronouns.

Ego, tu, ille,

I, thou, and Billy,

Is, sui, ipse,

Got very tipsy.

Iste, hic, meus,

The governor did not see us.

Tuus, suus, noster,

We knock’d down a coster-

Vester, noster, vestras.

monger for daring to pester us.

To these may be added, egomet, I myself; tute, thou thyself, idem the same, qui, who or what, and cujas, of what country.

DECLENSION OF PRONOUNS

Pronouns concern ourselves so much, that we cannot altogether pass over them; though a hint or two with regard to the mode of learning their declension is all that we can here afford to give. We are constrained now and then to leave out a good deal of valuable matter, for the reason that induced the Dublin manager to omit the part of Hamlet in the play of that name – the length of the performance.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Полная версия книги