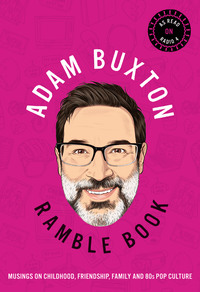

Ramble Book

They broke the news to me a couple of months before I left. Mum and Dad talked it up as a grand adventure – all midnight feasts, jolly japes and super new chums – but as far as I was concerned they may as well have said, ‘We know you thought we loved you and that your cosy life would never end, but in eight weeks we’re going to shoot you in the back of the head and dump you in a field in Sussex.’

Christmas 1978 played out with a bass note of melancholy, rising occasionally to mild panic at the thought of the looming intercision. The same questions kept going through my mind: Why are they doing this? Who does this really benefit? Could there not be a second referendum? (NOTE TO EDITOR: Re. your insistence that this is a lame, outdated, topical joke that ought to come out – I absolutely disagree. People LOVE Brexit references, they always will, and I forbid you to remove it. Get rid of this note, though, obviously.)

On a freezing Sunday evening in January 1979, my parents drove out to Sussex to drop off their nine-year-old son at his new boarding school, a big Queen Anne-style house of imposing wood-panelled rooms and corridors that smelled of floor polish and disinfectant, behind which lay a complex of newer buildings, all surrounded by playing fields and woodland.

Mum and Dad carried my suitcase and new tuck box as a smiling senior boy showed us the way to my dormitory, his presence encouraging me to keep it together and act as if this was a super adventure rather than an inexplicable nightmare. Whereas my parents had found it easy to coo over the posh interiors downstairs, the harshly lit dormitory with its rows of little metal bunks presented more of a challenge, and they began to look more sympathetic. Just as I was considering losing it dramatically, a woman in a light-blue nurse’s uniform appeared, who gently but firmly informed my parents that it was time for them to leave and that I would be fine. I looked at my mum as if to say, ‘I am NOT going to be fine,’ but before I could start bawling, she and Dad were gone.

The most painful parts of that first term at boarding school came whenever I phoned home from the call box in the corridor outside the dining room. Children queueing for dinner would watch as trembling ‘Squits’ like me jammed 10p pieces into the payphone, before becoming fully distraught once Mummy or Daddy picked up. A few times when my credit ran out, the coin-slot mechanism was too stiff for me to insert my next 10p, and the call was cut off in a din of beeps and sobs, so when Mum saw me next she explained how I could make a call from a payphone without money by just calling the operator.

‘I have a reverse-charge call from Sussex, will you accept the charges?’ the operator would ask when someone picked up at home. When I heard Mum’s lovely voice say, ‘Yes. Hello, Adam!’ I crouched beneath the glass panels in the door so no one in the dinner queue could see me and sobbed my nine-year-old tits off. I asked Mum about those tearful phone calls recently and she said, ‘Yes, it was the most awful feeling.’ So why send me away? She paused for a little while, then said, ‘Do you know, I’ve never really thought about it.’

My sister started at the same boarding school a year after I arrived, and a few years later my brother was sent there too, so Mum and Dad must have thought about it a little bit. I think they believed that the experience would ‘toughen us up’ (which they considered a worthwhile thing to do with a child), while also enabling us to ‘belong’ to the upper echelons of British society with access to all the privileges and protections that membership provided. I suppose they also hoped we might enjoy it.

The school was progressive in many way: co-ed, no uniform, lots of arts and crafts, drama and cooking (I was the Lancashire hotpot and treacle tart king), and after the initial shock I ended up having fun and making some good friends there. But when I left school and started working, living and going out with people who hadn’t been privately educated, my overwhelming feeling was not one of privilege but embarrassment. Perhaps I had an advantage if I’d wanted to become a Tory politician, a QC or a Harley Street physician, but outside the old boy network I felt that a public-school education just marked me out as a Merchant Wanker.

I didn’t mind when work colleagues teased me about my plummy accent, as long as they weren’t spitting with hatred as they did so, but it did make me self-conscious, and in my twenties I would occasionally experiment with life as a Mockney. If I got into a black cab and the driver was a chatty South Londoner who wanted to talk about football, I did my best to join in, not by pretending I knew about football, but by adopting a generic geezerish South London drawl that later became the voice I used for impersonating David Bowie. Meanwhile the cab drivers were probably thinking, ‘Why’s that posh geezer doing that weird voice?’ Either that or ‘Oh my God! I’ve got David Bowie in my cab!’

My eagerness to lose my accent would have distressed Dad, who throughout his children’s lives never missed an opportunity to correct what he considered sloppy pronunciation or grammar. If any of us said a word like ‘now’ without a sufficiently full and fruity vowel sound, he launched into his Henry Higgins routine: ‘Neh-ow? Neh-ow? It’s Nah-ow. Hah-ow, Nah-ow, Brah-own Cah-ow.’

When he got ill and moved in with us, I imagined sitting up late into the night with Dad, doing shots of whisky and morphine and recording him as I asked all the BIG QUESTIONS I’d never felt able to ask before: who his parents were, what the war was like, why things hadn’t worked out with Mum and why he’d thought it so important to send his children away to private school and have them speak with the ‘right’ accent.

The recordings would be poignant, personal and painful (ideally there would be some crying). I would turn them into an award-winning podcast and just before he died Dad would give me a hug and tell me how brave I was and that he was proud of me. But he hated all that sort of shit, so although we did have a few heavy conversations, they were not quite what I’d had in mind. As it turned out, most of our exchanges tended to focus on noodle preparation, men’s nappies and whether or not he had taken his pills.

For the first year or two after his death, thinking about Dad was always painful. My unanswered BIG QUESTIONS were supplanted by recollections of distressing moments from his last months that sometimes I was only able to dislodge by humming or singing to myself. (PRO-TIP: This works for all kinds of thoughts you would rather not deal with.) Over time the older, happier memories resurfaced and with them my curiosity about Dad and how he had become the posh old bloke I always thought of him as.

His self-published memoir The Road to Fleet Street, which he completed shortly before his death, covered his school years, his service in the Royal Artillery during the Second World War, his time studying modern history at Oxford after the war, some posh old bloke name-dropping (including Reginald Bosanquet, Robert Graves and Harry Oppenheimer) and his glory days as columnist and Travel Editor at the Sunday Telegraph. However, there was nothing beyond that point, and nothing about who his parents were or the experience of starting his own family, i.e. all the stuff I was most interested in. Perhaps he felt that writing about his family was indiscreet somehow, but I suspect he simply considered it irrelevant and uninteresting. Then I remembered The Proving Ground.

One of several self-published projects, The Proving Ground was a novel that Dad had started writing in the late 1980s when he was deep in debt and had just been laid off by the Telegraph. He finished it around 2001, a year or two after he and Mum finally separated. It’s the story of a travel journalist on a Sunday newspaper whose money problems are solved when he discovers a cache of gold during a trip to Alaska. The Proving Ground gave Dad an opportunity to cast himself as a heroic figure at a time in his life when he felt embattled, misunderstood and perhaps not completely certain that the sacrifices he had made for his family had been worth it.

Via his protagonist, David Barclay, Dad set out his values and detailed his fantasies with a directness he would normally have avoided. The characters along with certain events from his own life were so thinly fictionalised that when he showed it to me, my brother and sister, we agreed among ourselves that it made for a strange read.

The Proving Ground begins with David Barclay working at the Sunday Messenger (clearly meant to be the Sunday Telegraph). He has three children – Luke (clearly me), William (clearly my brother, Dave) and Sophie (clearly my sister, Clare) – who are receiving an expensive private education that is beyond their father’s means.

Barclay is married to Margaret (clearly my mum, Valerie), a shrill woman who doesn’t understand him and doesn’t respect the passionately held principles that have led to his financial woes. I think Pa chose the name ‘Margaret’ for Mum’s character because of Princess Margaret, who he found irritating.

The novel begins with Dad – I mean David Barclay – attending a crisis meeting at his bank, ‘Mallards’ (clearly meant to be Coutts & Co. where Dad held an account for a while). The manager at Mallards is a rude young man who tells Dad – I mean David Barclay – that sending his children to private school is financially reckless. There follow several pages of justification from Dad – I mean David Barclay – about the benefits of a boarding-school education:

A close relation had asked me recently if I was quite sure that I was right to beggar myself, not to mention Margaret, for what many people might see as a social prejudice. A social prejudice? … I never saw William in the orchestra at Haileybury without intense satisfaction that he was in the brass section there in Old Hall, not an overcrowded London flat, watching television.

Beggaring ourselves? My parents had striven only for their children; was I to betray mine by any inferior devotion? Sure we were right? I never picnicked on the lawns at Sophie’s prep school in Sussex on ‘Open’ or Sports Day without knowing beyond a doubt that for a child to have the benefits of that particular school’s environment for a start in life was worth whatever it might cost.

A few pages on, still restating the case he wished he’d made at the meeting with the rude bank manager, Dad – I mean David Barclay – continues to explain why he considers a private education so important:

To see William in Haileybury’s elegant, spacious ambience always gave me the deepest pleasure. Everything about the place, from the well-tended lawn to the 1,300 names on the War Memorial panels in the cloisters, induced an awareness of a history richly imbued with all that seemed to me best in Britishness and the nation’s imperial past, and all that seemed most admirable in English public school education and upbringing. That William now belonged here, sharing in so great an inheritance, gave me a satisfaction I hardly dared acknowledge for fear of tempting fate.

There are still many people who feel the same way that my dad did about public schools, though in an age in which social inequality is generally considered to be something worth struggling against and working-class credentials, even fake ones, are proudly flashed at every opportunity, the pro-public-schoolers are sometimes less keen to advertise their enthusiasm.

I’d always assumed that Dad’s fondness for the British establishment and his apparent aversion to all things working class was evidence that he himself was an old-school toff, something we played for laughs in his BaaadDad segments on The Adam and Joe Show. Then a couple of years after his death I made a long-overdue trip to visit my aunt in Wales.

Dad had five older brothers and a younger sister, Aunty Jessica. When I was at boarding school Jessica would sometimes come and take me out on weekends and feed me cake and biscuits until I threw up. I loved Aunty Jessica. Then we didn’t see her for a long time and Aunty Jessica became another member of our extended family that we seldom heard about, though she and Dad remained in occasional contact. I emailed her to ask if I could visit and ask about their upbringing, and she sent me a warm reply saying that I’d be welcome, but I’d better be quick because she was 91.

The following week I drove from Norfolk to Wales.

It was good to see Aunty Jessica again. After some cake, biscuits, hardly any vomiting and a bit of catching up (‘Now, can you tell me what exactly a podcast is?’), Jessica told me about the grandparents I’d never met and the background that had primed Dad for a life dedicated to embracing the ruling classes.

It turned out that my grandfather, Gordon Buxton (who died long before I was born), had been a servant boy, a butler and a chauffeur before becoming an estate overseer for a wealthy family in the village of Cowfold, Sussex. He was known as ‘Buckin’ or ‘Bucky’. In return for Bucky’s service his wife and family got a house to live in, for which they were grateful. This was back in Downton Abbey days when, as Jessica told it, the lower classes were well looked after by their employers and ‘knew their place’, and everything was simpler.

When the First World War broke out my grandfather’s boss, a Lieutenant Colonel, asked Bucky if he would travel with him to France to be his war bitch (not Jessica’s phrase). Bucky was eager to oblige, despite having to leave behind his wife and three children (not including my dad, who was born after WWI). When the Lieutenant Colonel was killed on the first day of fighting at the Battle of Arras on 9 April 1917, Bucky carried his body off the battlefield and, upon returning to Sussex, continued to serve his widow and children. In Downton Abbey terms, it seems Bucky was more of a Bates than a Carson.

The continued patronage of the Lieutenant Colonel’s regiment and family meant that my father was able to get on his social mobility scooter and attend the local grammar school before starting at the Imperial Service College in Windsor, a notoriously brutal and disciplinarian boarding school dedicated to preparing boys for military life. Teachers and senior boys at the ISC would regularly beat the younger ones with a cane until they bled for infractions like attending chapel with dirty shoes, failure to wear your school hat while visiting town or walking around with the collar of your overcoat turned up, unless you were a prefect or had been awarded a sports prize.

In addition to the jolly corporal punishment larks, my father was regularly taunted for not speaking with a sufficiently posh accent (something he absolutely nailed in later life). He became so keen not to stand out that whenever it was time for his parents to pick him up, my father insisted they meet him outside the school and down the road a short way. Dad worried that, next to the Daimlers, the Bentleys and the Rolls-Royces of the other parents, the Buckymobile would look too shit and he would get more grief from the toffs. Grandfather Bucky would tell my dad, ‘The people who care don’t matter because the people who matter don’t care.’

Years later, when it was my turn to be worried about being judged for not having the latest cool thing, my dad repeated Bucky’s advice, but I was confused. ‘You mean the people who care about me don’t matter?’

‘No, the people who care what car your parents drive or what clothes you wear, they don’t matter.’

‘Oh. Well, maybe you should say, “The people who mind don’t matter and the people who matter don’t mind”?’ Dad sighed.

His son, not for the last time, was being too literal, but I remembered the saying. It’s a good one I think, but not always easy to take comfort from.

RAMBLE

Dad was impressed by successful people, even if they had become successful doing something he didn’t approve of. After returning from a business trip in the late Seventies he asked us excitedly, ‘Have you heard of some musicians called Who? I sat next to the singer on the plane!’ We eventually established he was talking about Roger Daltrey. ‘He was a thoroughly decent fellow. We talked about the joys of salmon fishing,’ said Dad.

Other celebrity encounters that left Dad uncharacteristically exuberant included Larry Hagman (aka J.R. of TV soap Dallas), the rapper Coolio, who drove Dad round Los Angeles in his Humvee for The Adam and Joe Show, and pop’s nicest guys, Travis, who Dad met at my wedding in 2001. Going through his belongings after he died, I found Dad’s address book and saw that he’d collected the phone numbers of Dougie and Fran from the band. They were both under ‘T’ and next to their names Dad had written ‘Travis – Pop Stars’. Well, you never know when you might need a pop star.

In 1998, when Joe and I were flying to LA with Dad to do some filming, he used his old travel-editor contacts to wangle a seat in first class, where he found himself sat beside The Pretenders’ singer Chrissie Hynde. Sadly, the salmon-fishing banter that had bonded him and Roger Daltrey all those years before failed to beguile Chrissie and she asked to be moved to another seat.

The Imperial Service College, the public school Dad attended, later merged with and changed its name to Haileybury. It’s where David Barclay – I mean Dad – sent my brother Dave to school, and I think he loved the symmetry of having his son ‘belong’ to an institution at which he’d worked so hard to be accepted. In 1991 the real-life crisis meeting with his unsympathetic young bank manager resulted in Dad having to take Dave out of Haileybury while he was studying for his A levels. Pa considered it a failure for which he never forgave himself.

But Dave’s fine. And anyway, who really belongs anywhere? I think that whole idea of ‘belonging’ and ‘not belonging’ is too often used to keep people ‘in their place’. But I suppose that’s easy for me to say, having enjoyed untold rewards from attending the kinds of schools I did and meeting the people I met there. Like it or not, that’s thanks to Dad and his crazed determination to climb and to ‘belong’.

The thing that still seems odd to me about Dad’s idea of what constituted a desirable existence is that it was so closely correlated to social class. Though he detested the latter-day Etonian Tories and Bullingdon yobs, he remained throughout his life a conservative and a snob who found it hard to find value in what a person had to say if it was said with the wrong accent – the kind of accent that as a boy at the Imperial Service College he’d felt obliged to shed.

I never properly suggested any of this to him when he was alive, and it feels both gutless and redundant to say it now he’s dead and I can’t get the 10p in the slot, but I wonder if he would accept the charges.

CHAPTER 3

1980

My adolescence fell squarely in the 1980s and, for better or worse, the culture I consumed in that decade has played a significant part in defining my life ever since.

I look back at some of those Eighties influences with fondness and admiration for my good taste, but others evoke the sadness my dad felt about what I chose to fill my days with. To him it seemed as though I was living on a diet of worthless junk that would clog my intellectual arteries and lead to possible art failure. Now, in doubt-filled middle age, bringing up my own children as growing sections of society revise their attitudes to much of the culture and the values I grew up with, I often find myself thinking Dad might have had a point.

Where are the books? The trips to galleries or museums? The theatre? Where is the engagement with politics and social issues? The work by people other than men from the US or the UK? And when something genuinely worthwhile was put in front of me, even if eventually I ended up appreciating it, my initial response was usually to scrunch up my face in disgust, like a baby tasting caviar.

A decade of expensive private education, and all I had to show for it was a love of left-field pop music, an intimate familiarity with TV and mainstream cinema and the ability to quote a few Eddie Murphy routines (I use the word ‘quote’ loosely; basically I would fill any conversational lull by saying, ‘I got an ice cream and you ain’t got one’, ‘Goonie-goo-goo, with a G.I. Joe up his ass’ or ‘SERIOOOOO!’

Join me, then, as I revisit a few of the adolescent moments, along with their audio-visual accompaniment, that helped make me the towering genius I am today.

Pits, Pendulums and Dirigibles

The year 1980 began with me aged ten and starting my second year at the co-ed boarding school in Sussex that Dad always referred to as ‘The Reformatory’. I no longer cried when they dropped me off there but would still rather have been at home, eating Penguin bars and McDonald’s quarter-pounders and chips in front of The Dukes of Hazzard, Metal Mickey and Fantasy Island. And CHiPs. The cultural treats on offer at school may have been more nutritious, but they were harder to digest.

Most nights, when everyone was in bed, stories would play out over the PA system. Sometimes it was something fun like James and the Giant Peach, The Colditz Story, The Hobbit or some Greek myths, but on other nights we’d be treated to a profoundly upsetting helping of horror from M.R. James or, worse, Edgar Allen Poe. It was a kind of audiobook Russian roulette and you never knew if the chamber was loaded until the PA crackled to life and the story began.

I lay in my bunk, wide-eyed with dread in case the words ‘I was sick – sick unto death with that long agony’ came through the tannoy, because that meant it was ‘The Pit and the Pendulum’ time, and the next half-hour of homesick gloom was further darkened by Edgar Allen Poe’s story of physical and psychological torture during the Spanish Inquisition. ‘The Black Cat’ and ‘The Tell-Tale Heart’ would follow, by the end of which one or two children in every dormitory would be sobbing softly, and in the junior dormitories, wailing loudly. And that was just the bedtime stories.

One afternoon every weekend a film was projected onto the wall of the gymnasium. In the days before 24-hour mobile entertainment was considered a basic human right, these film showings were a big deal and I could be found sitting cross-legged on the wooden floor of the gym, regardless of what was playing. It was a varied programme that during my time included The Four Feathers, Kes, Capricorn One, Bugsy Malone, The Thief of Bagdad, Star Trek: The Motion Picture, Duel, One of Our Dinosaurs Is Missing, Ring of Bright Water, Jaws, Hooper, Smokey and the Bandit and Smokey and the Bandit Ride Again (as the Eighties dawned, Burt Reynolds was still considered one of cinema’s most alluring cishet fuckboys).

Along with lashings of Burt, they also served up some of the biggest and stupidest disaster films of the Seventies, and my first sense of how much could go wrong in the world came via school gym performances of The Towering Inferno, The Poseidon Adventure, Earthquake, Meteor and the Airport series. But nothing took a giant shit on my psyche quite like The Hindenburg and The Cassandra Crossing.

The Hindenburg was basically a ‘Whogonnadunnit’ that took place on a luxurious passenger airship in 1937. George C. Scott played a German colonel who has been warned of a plot to blow up the dirigible. Unaware that the film was loosely inspired by historical events, I expected George to foil the plot in the nick of time and prevent the airship from exploding. SPOILER ALERT: he doesn’t.