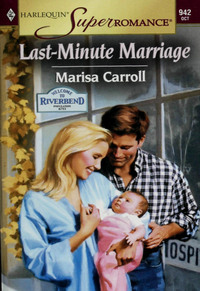

Last-Minute Marriage

No one but the cop who’d eyed her so suspiciously and then escorted her into town. And the man who’d been riding with him. The one with eyes the same rich brown as the plowed earth and a smile that lifted the left corner of his mouth a littler higher than the right. Mitch Sterling, the cop had said his name was. She wondered if he had anything to do with the big hardware and lumberyard she’d passed on her way down to the river. It had looked like a going concern. Not as big as the Home-Mart she’d worked for in Albany, but impressive for an independent in this age of mega-chain stores.

“Hi there. Remember me?”

She turned her head to find the man she’d been thinking about smiling down at her. His voice was low-pitched and a little rough around the edges, but as warm as his smile.

She didn’t smile back, although she was tempted. You didn’t smile at strange men in California. Or in New York, for that matter.

“Are you enjoying the view?”

“Yes,” she said. This time she did smile. She wasn’t in L.A. anymore. She was in God’s country. Or so one or two signs she’d seen along the roadside had proclaimed. “It’s very peaceful here.”

“It’s one of my favorite views.”

“You come here often?”

He propped one foot on the rose bed’s border, which was made of railroad ties stacked three deep. Real railroad ties, she’d noticed. Not those anemic landscape ties they’d sold at Home-Mart. This rose bed was going to be here for a long, long time. That was the way you built things in a place you never intended to leave.

“Most everyone in town does. But it’s the same view I get from my kitchen window.” He pointed down the way to a wide stream that emptied into the river. “I live in the yellow house over there.”

Tessa turned to follow his pointing finger, but she already knew what she would see. The house wasn’t yellow. It was cream-colored. Craftsman-styled, foursquare and solid with a stone foundation and big square porch posts. Roses grew on trellises on either side of the wide front steps. Pink roses, with several still blooming, like those in the park.

She loved history. Not so long ago it had been her intention to share that love of history by teaching. Not ancient history, or Colonial history. Not even Civil War history. But the history of the century just past. The enthusiasm and hubris of the early decades. The heartbreak of the Great Depression and the sheer determination required to survive those years. The heroism and sacrifice of the Second World War. The optimism and opportunism of the fifties. Even the strife and intergenerational warfare of the sixties.

The house Mitch Sterling indicated had seen it all. She wouldn’t be a bit surprised to find it had always been in his family. Riverbend seemed that kind of place, a town where families passed down houses and businesses and recipes from generation to generation. “It’s a great house,” she said. “How long has it been in your family?” The words had jumped off her tongue before she could discipline her thoughts.

“About ten years,” Mitch said, not looking at her but at the house. “I bought it when my son was born.”

“Oh.” She tried hard to keep the disappointment out of her voice. Such a little thing, the house not being in his family for a hundred years.

“I bought it from the family my granddad sold it to in ’74. My grandmother wanted something all on one floor, so he built her a ranch-style out by the golf course. But his grandfather built this house in 1902.”

“Your great-great-grandfather built the house?” She didn’t even know her great-great-grandfather’s name. And she envied him the luxury of knowing who had owned this house, when, and for how long. It meant he had ties here, roots that went deep.

“Yup. I thought it should stay in the family.”

“When I was growing up, I never lived more than three years in one place.” What in heaven’s name had possessed her to tell such a thing to a total stranger? She must be more tired than she thought. She stood up, levering herself off the swing with one hand on the thick chain that held it to the wooden frame.

Mitch Sterling leaned forward to steady the swing, but he didn’t try to touch her. She was oddly disappointed that he didn’t put his hand on her arm. She had the feeling his touch would have been as warm and strong as his voice and his smiling brown eyes.

She smoothed her hand over her stomach. The baby was sleeping, hadn’t made a move in an hour. Perhaps she’d been lulled by the sound of the river and the rustle of the wind through the trees along the bank. Tessa hadn’t let the doctor back in California tell her the sex of her baby. But she knew in her heart it was a girl. A daughter. Hers and hers alone. She raised her eyes to find Mitch watching her with the same quiet intensity she’d noticed the first time she’d seen him on the road outside town.

The silence was stretching out too long. “I have to be on my way. I want to make it to Ohio by tonight,” she blurted.

“You’ve got a long way to go.”

“I’ve come even farther.” All the way from Albany and back again, with a detour through Southern California. But Albany was home, because that was where she and Callie had settled after their mother died. It was where she’d worked days at the Home-Mart and gone to school at night to get her history degree. Until she’d met Brian Delaney, a high-school friend of her brother-in-law’s, and fallen head over heels in love with him, giving up everything she had to follow him to California.

She blinked. Lord, she’d been close to saying all that aloud to this stranger. It must be something in the clean clear air, too much oxygen maybe, and not enough smog. She took a step away from the swing, trod on a stone and stumbled a little.

This time he didn’t hesitate. He reached out and steadied her with a hand under her elbow. She was right. His touch was as warm and strong as the rest of him. “Are you sure you should be driving any more today? You look pretty done in to me.”

He didn’t mince words, obviously. Nothing like Brian, who tap-danced his way around everything—until it came time to tell her he was leaving her and the baby to follow his dream and play winter baseball in Central America.

“I’m fine, really,” she assured Mitch.

He didn’t look convinced. “It’s going to be dark in an hour. It’ll take you another hour after that to make it to the interstate. Why don’t you stay the night here? The hotel on Main Street was restored just a couple of years ago. The rates are reasonable. And it’s clean. It’s even supposed to be haunted. And the restaurant’s not half-bad, either,” he added, deadpan.

“I don’t believe you.”

He made an exaggerated X on his chest. “Cross my heart, the food’s good.”

A chuckle escaped her. “I mean, I don’t believe the hotel’s haunted. I always thought ghosts were unhappy spirits doomed to wander the earth until they were set free. What could have happened in a town like this to cause a ghost?”

His face clouded slightly. She felt the same chill she had when the sun dipped behind a cloud a few minutes before he showed up. “Riverbend’s not paradise,” he said. “Most small towns aren’t.” Tessa waited, wondering what he would say next. He was silent a moment, glancing out over the river. Then his frown cleared and the sunshine came back into his face. “But this place is probably as close as you’ll come to it. And as a member of the town council and the Chamber of Commerce, it’s my duty to roll out the welcome mat. Get in your car and I’ll show you the way to the hotel.”

“That’s not necessary.” She had no intention of spending the night in Riverbend or anywhere else. She couldn’t afford it even if the hotel rates were more than reasonable. They’d have to be giving the rooms away free.

She had no health insurance and less than two hundred dollars to her name. One hundred and seventy-nine dollars, to be exact. And her credit card. It was paid off, thank goodness, but she’d have to live on the credit line, and it was by no means a large one. It scared her to death to think about how nearly penniless she was.

But she wasn’t about to tell Mitch Sterling any of that, no matter how warm his eyes and his touch. How could he know how truly desperate she was? And how determined she was not to be beholden to a man to whom she and their baby were just an afterthought? Mitch Sterling was a member of the Chamber of Commerce and the town council. He lived in the sort of storybook house she had yearned for all her life, in a town that was the embodiment of the American dream. In a place like Riverbend, a man didn’t make a woman he professed to love pregnant and then leave her to follow his own dreams.

She had her pride left, even if she’d lost most everything else. And her pride wouldn’t let her tell this confident, self-assured man that she had no intention of sleeping anywhere but in her car. So she let him walk beside her the short distance to the parking lot. She followed him out, onto Main Street, and then, after he waited for her to park her car, into the high-ceilinged, spotlessly clean lobby of the River View Hotel. She smiled when he introduced her to the clerk, a gray-haired woman standing behind an antique partners desk that served as a reception counter. He told the clerk that Tessa was a stranded traveler and to give her the best room in the house.

Then he had shaken her hand and said goodbye. “I’m late picking up my son from his art lesson. It’s been nice meeting you.”

“Thank you,” she said, equally formal in front of the inquisitive eyes of the desk clerk. “I’ll always remember your kindness.”

“Goodbye, Tessa Masterson. Good luck in your journey.” He turned and left the building.

Where had Mitch Sterling learned her name? From his friend the cop, she supposed.

“Now,” said the clerk, “I imagine you’ll be wanting a nonsmoking room.”

“I…” She was going to say she didn’t want a room at all. But she betrayed her resolve by asking what the room rates were, instead of turning on her heel and marching out of the building to her car.

“Fifty-nine dollars a night, plus tax,” the woman said, spinning the antique desk ledger toward her. More than reasonable. But still too much. “We take credit cards,” she prompted.

Tessa was tempted. So very tempted. Just one night. She started to reach for the pen but caught herself. “I’m sorry. I’ve changed my mind. I really must cover some more distance tonight. I…I have such a long way to go.”

The woman’s smile faltered for a moment, then returned, polite but more distant now. “Certainly. I’m sorry you won’t be staying with us. Have a safe trip.”

“Thank you.” Tessa turned and hurried out through the etched-glass double doors and down the steps to her car.

She did need to cover more miles tonight. She really did.

The sun was still shining even though the rain clouds on the horizon were moving steadily closer. There were only a few more minutes of the beautiful autumn afternoon left. As long as the sun was shining, she would sit in the park and soak in the warmth and dream a little more of what her life might have been if she’d grown up in a town like this, with deep roots and strong family ties, instead of in the run-down part of a city in a series of shabby apartments with a mother who searched for love in all the wrong places and a father she couldn’t even remember.

She could do that. It would cost her nothing but another hour or so of her time. And it would give her back so much more. A few moments of peace and serenity that were worth their weight in gold.

IT STARTED TO RAIN just before sundown. The weather forecaster on the radio had said it would go on all night and most of the next day. Heavy fog was predicted for the morning, and school delays were a possibility.

If they canceled school he’d have to find someone to look after Sam, or else take him to the store with him. At ten and a half his son thought he was a grown-up. But Mitch didn’t feel right leaving him home alone all day. Even in a town like Riverbend, a kid could get into trouble. Especially a kid with a handicap.

If school was canceled, he’d take Sam to the store and let him price the new shipment of Christmas lights that had shown up yesterday afternoon. He’d even offer to pay him double his usual rate of two bucks an hour. Mitch wanted that Christmas-light display up before the end of the week. The big chain hardware out near the highway had had its Christmas lights out for weeks.

People in Riverbend were loyal to Sterling Hardware and Building Supply, had been for the seventy-five years since his great-grandfather had first opened the doors. They knew it might take Mitch a week longer to get his shipments of such must-have items as icicle lights, but he’d get them. And he’d come damned close to matching the big store’s prices. So they waited.

And Mitch tried his best to make sure they didn’t wait a minute longer than necessary.

Thinking of the new store out by the highway brought a frown to his face. He’d lost his best employee, Larry Kellerman, to them just the week before. Mitch was going to have to find someone to replace him soon. Trouble was, no one with Larry’s experience or business training had applied for the job yet, and with the Christmas season less than a month away, Mitch couldn’t afford to put a novice on the front lines. He’d have to take up the slack himself.

And then Sam would get the short end of the stick.

Not if he could help it, though. Sam had gotten the short end of the stick too often in his life. An ordinary sore throat when he was two had developed into a serious strep infection. His temperature had soared and for two days his life hung in the balance. Then when he’d emerged from the semiconscious state he’d fallen into, it had taken weeks for him to fully recover. And sometime, somehow, during the illness, Sam had lost a significant portion of his hearing.

Mitch’s world had rocked on its foundation. Some days it was still a little wobbly. Kara had tried, she really had. But Sam wasn’t an easy child to raise. There was the extra vigilance required to keep an inquisitive, hearing-impaired toddler safe, and all the therapy sessions and special preschool classes at the regional rehabilitation center forty miles away. If it hadn’t been for Mitch’s mother being there to help out…well, his marriage probably wouldn’t have lasted as long as it did.

But when Sam was six, his parents had died in a car accident on the sort of foggy night tonight promised to be. Kara had called it quits soon after, taking off for the bright lights of Chicago, where she could be free to find herself without the impediment of a handicapped son and a husband she’d “outgrown.” Now it was just Sam and Mitch and Mitch’s granddad, Caleb. And if it wasn’t the ideal arrangement for raising a child or living your life, Mitch was mostly content with the way things were.

He coasted to a stop in front of Lily Mazerik’s big old Victorian house and headed up the walk to the front door. He could have buzzed Sam’s pager and had him meet him at the curb. It was a special one that vibrated, instead of beeping when a message came in. But he wanted to say hello to Lily and ask her how Sam was coming along, so he hadn’t bothered. He turned the key on the old-fashioned metal doorbell and waited.

A moment later Lily appeared at the door wearing a paint-stained smock. Her silvery blond hair was pulled into a soft knot on top of her head. There was a smudge of paint on her cheek and a smile on her lips. “Hi, Mitch,” Lily said, stepping back so he could enter the house. “Do you have time to see Sam’s latest masterpiece, or are you in a hurry to get him home?”

“I’ve got time.”

“Good.” Her smile widened.

They’d been friends all through school and fellow River Rats, which was the name given the gang of kids who used to hang out together by the river. Over the summer Lily had fallen in love with Aaron Mazerik, the high-school coach and proverbial bad-boy-made-good. Aaron had also turned out to be the illegitimate son of Abraham Steele, the president of the bank and Riverbend’s leading citizen, who’d died of a heart attack back in the spring. The revelation had created speculation and gossip that had lasted most of the summer.

Mitch followed Lily to the back of the house. Aaron was nowhere to be seen, and Mitch figured he was probably at the gym. Preconditioning for basketball season had started that week even though football season was still in high gear. Lily and Aaron’s romance had had tough sledding for a while, but it looked as if everything was working out for them now. They’d been married in a quiet ceremony right after Labor Day.

Actually, when he thought about it, a lot of his old River Rat pals were pairing off. Charlie Callahan and his ex-wife, Beth, were back together after a fourteen-year separation. Mitch had promised Charlie he’d be best man when they retied the knot on Valentine’s day. Lynn Kendall, the pastor at the Riverbend Community Church, and Tom Baines were seeing a lot of each other, and Mitch wouldn’t be a bit surprised if something serious developed there.

He was the only one of the bunch left single except for Nick Harrison, who was now his lawyer, and Jacob Steele, Abraham’s legitimate son. But for all he knew, Jacob could be married with a dozen kids by now, or he could be in jail, or dead. No one in town had heard from him in years, not even his aunts Ruth and Rachel. His old friend hadn’t even come home for his father’s funeral, and Mitch didn’t have any idea why.

“Dad!” Sam looked up from the table in Lily’s kitchen where he was sitting. “See what I did?”

“Hey, tiger,” Mitch greeted him, moving past Lily to look down at Sam’s drawing.

“It’s…Mothra destroying Tokyo and…Godzilla’s coming to the rescue of everyone in that building Mothra’s going to step on.” Sam smiled and shrugged. “How’d I do?” He’d made a hash of the monsters’ names, but Mitch wasn’t in the mood to correct him.

“Not too bad. We’ll add them to your vocabulary list and practice later. Your picture’s great.” Mothra and his nemesis, the legendary Godzilla, were towering over the hapless Japanese capital, tiny human figures cowering at their feet. Perspective had obviously been the lesson of the day.

“He’s one awesome dude.” His son’s smile reminded Mitch of Kara. Sam had his mother’s blond hair, which turned almost white under the summer sun, blue eyes and one crooked front tooth. But Mitch also recognized himself in the boy. He had the Sterling square jaw and a nose that was going to be too big for his face for a few years to come.

He ruffled Sam’s hair. He was a good kid—an antidote to all the lonely nights and lonely years that stretched ahead of Mitch. There he was, thinking about being alone again. “Tell me how you did this,” he said a bit grimly.

“It’s called perspective,” Sam explained, enunciating as clearly as he could. Mitch shot Lily a grateful look. It was obvious she’d taken the time to help Sam with the word. “I’m learning how to make things look bigger and smaller just like you see them in real life. See, Mothra is fifty feet taller than Godzilla, but that doesn’t mean anything. He’s still going to get his ass whipped.”

“Sam!” Lily’s eyes widened, but the corners of her mouth twitched in a suppressed smile.

“Whoa, son.” Mitch laid his hand on Sam’s shoulder and applied some pressure so Sam would understand the importance of his words. “That’s not a term you use in front of ladies. In fact, it’s not a word you should be using at all.”

Sam clapped his hands over his mouth. “Oops, sorry,” he said, signing the apology for good measure. “It just slipped out. I mean, Godzilla’s going to kick butt.”

“Well, that’s some improvement,” Mitch said.

“You’re forgiven,” Lily told Sam. “How do you sign ‘forgiven’?”

Sam showed her and she tried to repeat the swift movements of his hand and fingers. Mitch encouraged Sam to use spoken words as much as possible even though he knew sign language. It was a controversy in the world of the hearing impaired, sign versus speech, and Mitch had listened to both sides. But he’d decided that everyone Sam encountered would speak to him, and only a very few would sign. So they’d put most of their emphasis on speech therapy.

“Slow down,” she said with a laugh. “I can’t keep up.”

“Practice,” Sam teased, but the r sound slid away as it so often did. Consonants were particularly hard for his son to reproduce, since he’d lost his hearing before he was fully verbal, but Lily understood and rolled her eyes.

“Very funny. I’ll practice signing. And you practice your perspective. Is it a deal?”

“Deal,” Sam said.

“Okay. Your assignment for next week is to draw something you can see from your bedroom window using the proper perspective, okay?” She had been looking directly at him as she spoke. She formed her words carefully and didn’t speak too quickly so Sam could read her lips.

“I promise. Can I take my picture home tonight to show Granddad?”

“Sure.” Lily produced a heavy cardboard folder to protect Sam’s picture from the rain on the trip home. “See you next week, Sam.”

“See you. Come on, Dad. I want to watch Unsolved Mysteries.”

“Homework first.”

Sam wrinkled his forehead into a frown. “I’m sick of school already.”

Lily laughed. “It’s only October.”

“Tryouts for basketball are in four weeks,” Sam told her. This was Indiana. Basketball season was as real an indicator of the passing year as falling leaves.

“You’ll make the team this year, I know it,” Lily said. “Aaron’s told me how hard you’ve been working all summer.”

“Really?” Sam brightened at the praise.

“It all depends on your report card,” Mitch reminded him with a touch on his shoulder so Sam would look his way. “Now come on. Granddad is waiting for us, and he’ll want to see your drawing, too.”

Sam picked up his backpack where he’d left it beside the front door. “He’s very talented, Mitch—before you know it, I’ll have taught him all I can,” Lily said, stopping Mitch with a hand on his arm. “If he keeps progressing at this rate, we’ll have to contact someone at the university to work with him.”

“Whoa. You’ve only been giving him lessons since school started. You’re making it sound like I’ve got a budding Rembrandt on my hands.”

“Well, I may be overstating things just a bit,” Lily admitted. “But he’s good.”

“If he works at it,” Mitch added.

“That, too. But he is only ten. Discipline comes with maturity.”

“And he’d rather be Michael Jordan than Michelangelo.”

Lily sighed. “Yes.” She knew how sports crazy Sam was. And that his small size and his hearing impairment were holding him back from competing with the same skill and success as his friends. “You’ll work it out.”

“Yeah. We’ll manage.” Mitch shoved his hands in the pockets of his jacket. “We always do. At least with old Abraham’s bequest to Sam, finding money for special lessons won’t be a problem.” He still had no idea why the town patriarch had left his son nearly $27,000, and he probably never would, although his grandfather Caleb insisted it had something to do with him fishing Abraham out of the river after he’d fallen through the ice when they were boys. “Tell Aaron I said hello.”

“I will. Goodbye, Mitch.”

“Goodbye, Lily.”

“Bye, Sam,” she called. But he was already halfway down the brick sidewalk and couldn’t have heard her, anyway. “Tell him I said goodbye.”

“Will do.”

They didn’t talk in the car on the way home. It was too dark for Sam to read lips, or sign and be seen, for that matter. They drove past the park, and Mitch caught the quick reflection of taillights in the parking lot as they made the turn. He wondered who was there after dark on a rainy night like this.

No matter. Ethan or one of his men would take a swing through the park later, and if the car was still there, they’d check it out.

He pulled the truck into the driveway, and Sam hopped out, holding his drawing carefully in both hands. He sniffed the wet air. “Smells like fog,” he said, turning so that he could see Mitch’s response in the fitful glow of the porch light.