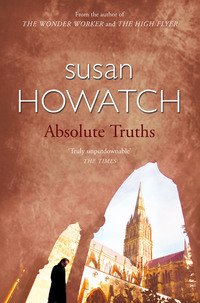

Absolute Truths

I read the leading books as recommended by the most important theological and ecclesiastical journals, but this was no chore because I was being myself, indulging in one of my favourite pursuits. I enjoyed a book if I agreed with its propositions, and if I disagreed with them I enjoyed the book even more because I had the opportunity mentally to tear it to pieces. I loved demolishing a slipshod theological construct, just as a counsel for the prosecution loves demolishing the case for the defence in a court of law. I was often asked to write reviews, and my cool, lucid little paragraphs had earned me bitter enemies. Periodically my opponents tried to soothe their wounded egos by demolishing my own books, but this was an uphill struggle for them because I applied to my theology a logic and scholarship which my enemies, if they had any professional integrity, were reluctantly obliged to acknowledge. Revelling in these academic battles I found each clash greatly stimulating.

My spiritual director was keen that I should read exactly what I liked during this period of early morning solitude. I often thought another spiritual director would have queried this self-indulgence, but Jon realised that the more eminent I became in public life the more I needed to have this time to exercise my intellect, my special gift from my Creator. So on that particular morning I read just as I always did, my brain skipping from concept to concept in an ecstasy of intellectual satisfaction, and when I had finished this treat I washed, shaved and dressed before setting off to the Cathedral for matins.

In accordance with tradition, the Cathedral offered the full range of services every day. During the week and on Saturdays these consisted – at the very least – of matins, Holy Communion and evensong, the latter being usually a service sung by the Choir, and on Sundays this weekday programme was elongated into a sung matins and a sung Communion in addition to the sung evensong. (In 1965 the Dean was still refusing to convert the sung Communion into the main Sunday service and refer to it as the Eucharist.) I never cease to be amazed by the idea, prevalent among the unchurched masses, that nothing now happens in cathedrals except the occasional royal wedding, but perhaps this misunderstanding arises from the fact that apart from the chaplain, the guides and the flower-arrangers, no devoted local supporter of the Cathedral would dream of visiting it between ten and four when the tourists rule the roost. The twentieth-century revival of our cathedrals as places of pilgrimage must certainly be welcomed as a manifestation of the Holy Spirit, but the swarming hordes can be disconcerting to anyone in search of peace and quiet.

Leaving the South Canonry on that cold, dank winter morning, I took the short cut across the Choir School’s playing field and began the short walk up Palace Lane towards the wall of the cloisters. The Cathedral, invisible at first in the darkness, began to take shape as I approached so that I was reminded of a sculpture emerging mysteriously from a block of stone. A masterpiece of English perpendicular architecture, built within the short space of forty years with no later additions, its eerie perfection so dominated its surroundings that it seemed to wear the darkness with the nonchalant elegance of a beautiful woman modelling a long black velvet gown. As I drew closer I fancied that the dawn, which was about to break, was making the Cathedral vibrate in anticipation. Beyond the wall nearby birds had begun to sing in the branches of the ancient cedar tree in the cloister garth.

A bishop need have little to do with his cathedral; the running of the building is not his business, even though he remains ultimately responsible for the spiritual welfare of all who work there. However, although tradition required that I should keep a certain distance from those who did run the Cathedral – the Dean and the three residentiary Canons who formed the Chapter – I had felt driven in the early days of my episcopate to set the pace in the matter of daily worship. That was because of the shortcomings of my enemy, the Dean.

Let me say at once that Aysgarth did have virtues: he had a good brain, a talent for administration, a genius for fund-raising, a not inconsiderable gift for forceful preaching and a certain range of social skills which made him popular in Starbridge. A self-made man, he had a chip on his shoulder about his origins in Yorkshire where his father had been in trade. This inferiority complex manifested itself in frequent references to the fact that he had read Greats at Oxford. (He was a scholarship boy, of course.) Not having a degree in theology he was hostile to those who had, but I must in all fairness concede that he was a sincere Christian. Unfortunately, after an upbringing among the crudest kind of Non-Conformists and an intellectual reaction in which he had embraced the wildest forms of Liberal Modernism, his theological outlook was, to put it kindly, confused.

When he became Dean – at the same time as I became Bishop; a testing stroke of providence – he made no secret of the fact that he disapproved of the habit of receiving the sacrament more than once a week, and that he thought auricular confession was Papist poppycock. One simply cannot go around making those sort of statements if one is the dean of a great cathedral in the middle of the twentieth century. I concede that one may be allowed to think them; after all, in our broad Church Protestants and Catholics are equally welcome, but such thoughts should be kept private and balanced by a determination not only to be tolerant of the other side but to learn from it. The older cathedrals in England are shrines to the pre-Reformation Catholic tradition and are now witnesses to our famous Anglican ‘Middle Way’ where the Catholic theology of the sacraments embraces the Protestant theology of the Word; in consequence a dean has no business making inflammatory statements in the manner of some Non-Conformist fanatic who bawls out: ‘No Popery!’ whenever he sees a statue of the Virgin Mary.

Fortunately Aysgarth was no fool and he soon realised he had to modify his stance in order to avoid giving offence to a great many people. He backtracked on auricular confession, although he refused to hear penitents himself, and he swore devotion to the cause of ecumenism, the reconciliation of the different branches of the Church, although his statements were strangely silent on the subject of Rome; I suspect he confined his ecumenical yearnings to union with the Methodists. But despite this improved behaviour he still failed to show up regularly at the early morning weekday services, and during the months when he was officially ‘in residence’ he constantly delegated the saying of matins and the celebration of Communion to one of the minor canons. (Lyle said Aysgarth needed the extra time in bed in order to recover from his hangovers, but this charge was not evidence of Aysgarth’s drinking habits but of Lyle’s dislike.)

The upshot of all these abstentions from public worship was that I soon felt obliged to give the residentiary Canons the spiritual lead which he was apparently unwilling to provide, so I started turning up more regularly at the Cathedral’s early services. I was careful not to exaggerate my response. I did not turn up every day. But I appeared at least twice during the week and often three times.

That made Aysgarth reform with lightning speed. His competitive nature ensured that he could not bear to be outshone by me, particularly on his own territory, and the embarrassing absences ceased.

This tense game of spiritual one-upmanship, with all its revolting worldly implications of rivalry, dislike and distrust, was played between us for six years in an atmosphere which, despite repeated clashes of opinion, we managed to keep tolerably civilised. By that I mean we never actually had a row, although we often came close to one. Then in 1963, as Jon put it in his old-fashioned way, ‘the Devil wriggled into the Cathedral and caused havoc.’ It is not my purpose now to describe the events of 1963, but this was the year when Aysgarth commissioned a pornographic sculpture for the Cathedral churchyard.

I regret to say that there was even more going on than this row over the sculpture (the commission was eventually cancelled), but I still cannot bring myself to write about what Aysgarth was getting up to on his days off. Some forms of clerical misbehaviour really do have to be buried six feet deep for the good of the Church. I think I may divulge, however, without going into lurid detail, that his two most dangerous habits at that time were a tendency to drink too much and an inclination to be undignified with women many years his junior.

Naturally I wanted to sack him, but I had no power. The Deanery was a Crown appointment, made by the Prime Minister on the Queen’s behalf, and although I could have threatened to make a considerable fuss in high places in an attempt to extort his resignation, it had seemed clear that my duty was to conceal the scandal, not risk exposing it. In the end I took the pragmatic course, aiming for rehabilitation by forcing Aysgarth to pray about his situation with Jon’s guidance, and fortunately by that time Aysgarth was so shattered by the consequences of his aberrations that he did not even have the strength to whisper: ‘No Popery!’ when compelled to seek help from an Anglo-Catholic spiritual director.

Jon patched him up until he was once again capable of running the Cathedral with dignity. Then Jon began the task of patching up me. I was the bishop, and in the manner of Harry Truman I could have kept on my desk a sign which read: THE BUCK STOPS HERE. There could be no denying the fact that the cathedral of my diocese was in a mess, and like Aysgarth I had to kneel before God, confess my part in the disaster and pray for the grace to do better. It was only after this ritual had been performed that Jon and I tried to work out how to cleanse the poisoned atmosphere and mend the fractured community.

Jon never held a session which Aysgarth and I both attended, but he suggested to each of us that the Bishop, Dean and Chapter should all make a habit of praying together, and when he judged that the moment was right I held a meeting at the South Canonry. Here it was agreed that for six months all five of us would attend matins daily and all five of us would participate together in the early service of Holy Communion at least once during the week. I also suggested that once a month we all met at the South Canonry to discuss any contentious issues in a calm atmosphere over coffee.

Life improved. The coffee meetings were a failure, since everyone was so nervous of a quarrel that nothing contentious was ever discussed, but at least afterwards the Canons were more willing to confide in me whenever Aysgarth drove them to distraction. Meanwhile the daily attendance at weekday matins had become a successful routine and we all stayed on for Communion on Wednesdays. This agreed pattern of worship should have meant that Aysgarth and I were free to abandon our game of spiritual one-upmanship, but I noticed that whenever I chose to exceed the agreed pattern and stay on for an additional Communion service, he usually stayed on too. However I thought it best to try to believe this was because of changed spiritual needs and had no connection with our old rivalry.

I must at this point give credit where credit is due and admit that Aysgarth worked just as hard as I did to eliminate the spiritual decay which had affected our community. He kept himself sober, behaved immaculately with young women and worked hard to raise money to restore the Cathedral’s crumbling west front. It was then I realised that Aysgarth’s principal talent, the one which outshone all the others, was for survival.

It would be untrue to say we became friends, but we did make elaborate attempts to be pleasant to each other. ‘And bearing in mind our temperamental incompatibility,’ I said to Jon, ‘even elaborate attempts to be pleasant must represent some sort of modest spiritual triumph,’ but Jon immediately became very austere.

‘I agree it’s a triumph,’ he said, ‘but it’s certainly neither modest nor spiritual. It’s a gargantuan triumph of the will fuelled by pride and self-deception, and all that’s really happening is that you’re passing off a spurious affability as a Christian virtue. Phrases such as “temperamental incompatibility” and “modest spiritual triumph” actually fail to describe or explain anything that’s going on here.’

I was baffled. ‘But Aysgarth and I are temperamentally incompatible!’

‘I see no evidence of that. You’re both intelligent men capable of strong passions and deep commitment. In fact I don’t see you as incompatible at all, temperamentally or otherwise – you’ve actually got a lot in common. You’re both well-educated men in the same line of business. You both enjoy fine food, good wine and the company of attractive women. You’re both devoted to your children.’

‘Yes, but –’

‘Your present attitude to Aysgarth says a great deal about your desire to behave like a good Christian, but very little about your desire to take the essential Christian journey inwards and examine your soul to work out what’s going on there. Perhaps if you were to take another look at the writings of Father Andrew, who was not only a modern master of the spiritual life but a man of immense humility and psychological insight …’

I did meditate on the passages Jon marked for my attention, but I regret to say I did not like Aysgarth any better afterwards. I could only redouble my efforts to treat him in the most Christian way I could devise.

It had been arranged that we should take the short service of matins together on that particular morning in February, I recited the office and leading the prayers, he reading the assigned passages from scripture, and when I entered the vestry of the Cathedral shortly before half-past seven I found he was waiting for me. I assumed that the three Canons had already taken their seats among the congregation in St Anselm’s chapel.

‘Hullo, Charles! Tiresome sort of weather, isn’t it?’

‘Very dreary. I hope it doesn’t snow and disrupt the trains.’

‘Going anywhere special today?’

‘Just nipping up to town for a committee meeting at Church House.’

‘Rather you than me!’

This concluded our opening round of pleasantries and was, as a golfer might say, par for the course. Aysgarth smiled at me benignly. When I had first met him long ago in 1940, he had been reserved, serious and not unappealing in his appearance despite that lean and hungry look which is always supposed to indicate an oversized ambition. Now, many double-whiskies and many sumptuous dinners later, he was stout and plain with a racy social manner which bordered constantly on frivolity. Being short, he was probably grateful for his thick hair which added a few precious tenths of an inch to his height. The hair was off-white and untidy, calling to mind the fleece of a bedraggled sheep. His blue eyes were set above pouches of skin in a heavily lined, reddish face, and his thin mouth, suggesting obstinacy, aggression and a powerful will, marked him as a forceful personality, someone who had no hesitation in being ruthless when it suited him. For some reason, which must remain one of the unsolved mysteries of sexual chemistry, women consistently found this tough little ecclesiastical gangster attractive. The phenomenon never ceased to astonish me.

As I took off my coat I carefully embarked on a second round of innocuous conversation. ‘How very kind of you, Stephen,’ I said, ‘to give Charley lunch yesterday.’

‘Not at all,’ said Aysgarth, following my example and toiling to be agreeable. I had thought he might make some comment on the lunch and perhaps even mention Samson, but he asked instead: ‘How’s Michael? Dido told me he came down to see you yesterday.’

I quickly moved to protect my Achilles’ heel. ‘Oh, Michael’s fine, couldn’t be better!’ I said, taking care to exude the satisfaction of a proud parent. ‘How’s Christian?’

Christian, Aysgarth’s eldest son and the apple of his eye, was a don up at Oxford.

‘Oh, doing wonderfully well!’ said Aysgarth at once. ‘I’m so lucky to have sons who never give me a moment’s anxiety!’

Instantly I grabbed hold of my temper before I could lose it, but it was still difficult not to shout at him: ‘Bastard!’ I knew perfectly well that Aysgarth was remembering Charley, running away from home, and Michael, being flung out of medical school, while the Aysgarth boys had journeyed through adolescence without ever putting a foot wrong. Aysgarth had four sons from his first marriage, all of whom were highly successful and utterly devoted to him.

‘Is Christian working on another book?’ I enquired politely, but I was unable to resist adding the barbed sentence: ‘I hope I’ll find it more original than his last one.’

‘Ah, but the influence of classical Rome on medieval philosophy isn’t quite your subject, is it, Charles?’ said Aysgarth, delivering this lethal riposte without a second’s hesitation. ‘If you’d read Greats up at Oxford, as I did, you’d find that Christian’s scholarship was more within your intellectual reach.’

The worst part about Aysgarth, as I had discovered to my cost in the past, was that he was a killer in debate. One entered an argument with him at one’s peril, but of course, as Jon would have instantly reminded me, I had no business getting into an argument with Aysgarth at all.

Fortunately the entry of the verger put an end to this serrated conversation, and when I was ready we were led silently through the Cathedral to the chapel where the daily services were held.

I could not help thinking that my visit had begun on a singularly unfortunate note.

Much depressed I prayed for an improvement.

VI

The congregation stood up to greet us as we entered St Anselm’s chapel, and I saw that all three residentiary Canons were in the front row. The most senior was Tommy Fitzgerald, who had once confessed to me that Aysgarth was the only man he had ever wanted to punch on the jaw, and next to this normally unpugnacious Anglo-Catholic stood Paul Dalton, who had once told me he hardly knew how to face a Chapter meeting without having a nervous breakdown. On the far side of this normally stable churchman of the Middle Way was the newcomer to Starbridge, Gerry Pearce, whom I had selected for his staying power after his predecessor, a crony of Aysgarth’s, had decamped to London as a direct result of the 1963 crisis. Gerry was a moderate Evangelical who had spent some years as a missionary in an unpleasant part of the world before returning to England for the sake of his growing family; I had poached him from the Guildford diocese where he had passed five arduous years persuading the affluent middle-classes that there was more to life than making money in London. Coming from an affluent middle-class area of Surrey myself I was in a position to appreciate his achievement.

I did not care greatly for Tommy Fitzgerald, an unmarried fusspot who in his own way could be just as pigheaded as Aysgarth, but I liked Paul Dalton, who had read divinity long ago at Cambridge, just as I had, and who was so devoted to cricket that he seldom left his television set when a test match was being broadcast. Apart from a tendency to wander off the point in diocesan committee meetings, Paul’s most tiresome habit was to complain how difficult it was to remarry. Since his wife’s death he had tried hard to find a suitable replacement, but he had never found anyone who matched his rigorous specifications. Lyle said he did not want to remarry at all but merely felt obliged to go through the motions of pretending that he did, but having been obliged to listen to Paul’s confidential opinions on the subject I knew that unlike Tommy Fitzgerald he was not happy as a celibate.

Beyond the three Canons who were gathered in the chapel that morning I recognised the Vicar of the Close, who conducted the day-to-day pastoral work for the Dean, and in the same row I noted three retired clergy and my two chaplains, all of whom lived nearby. A couple of devout laymen from the diocesan office and half a dozen equally devout elderly women formed not only the remainder of the congregation but the loyal core of the Cathedral’s band of regular worshippers.

I was about to conclude my quick inspection of those present when I saw there was a stranger among us. This was very unusual. As I have already indicated, few people chose to attend a weekday ‘said’ matins on a dark winter’s morning, and usually the Starbridge visitors who attended church during the week preferred to pass up matins in favour of Holy Communion at eight. I gave the stranger a sharp look, and as if sensing my interest he raised his head to stare straight into my eyes.

I blinked, taken aback. He was a priest, but a sinister one: swarthy, blunt-featured and built like a pugilist. His remarkable eyes, black and hypnotic, were set deep in shadowed sockets, and as soon as I had registered their potential power to cast a spell I found myself thinking: that man’s big trouble. And I wondered which bishop had the ordeal of keeping him in order.

The service started. When Aysgarth read the first lesson I stole another glance at the visitor and wondered if my instinctive distrust had been unjustified. He was conservatively dressed in a well-cut suit. His clerical collar was thick enough to look old-fashioned and his black stock was adorned with a small gold cross, hinting at an Anglo-Catholic churchmanship. The extreme respectability of his clothes formed a bizarre contrast to his sinister countenance and his curious aura of … But I could not quite define the quality of the aura. I could only think again: that man’s big trouble. And I could imagine not only all the women in his home congregation being disturbed by his powerful presence, but far too many of the men as well.

Towards the end of the service I briefly mentioned Desmond’s disaster and proposed that we all observe a moment of silence to pray for his recovery. Intercessions were usually made at the Communion service, but I felt that Desmond’s case should be presented to that tightly knit matins congregation. With the exception of the stranger we all knew each other and we all knew Desmond. In such circumstances I thought my request would call forth a particularly solid shaft of prayer.

After the service I adjourned to the vestry with Aysgarth for the short interval between matins and Communion, and soon we were joined by the three Canons.

‘Who was that man?’ demanded Tommy Fitzgerald.

But no one knew.

I asked: ‘Did no one introduce themselves?’

‘He gave us no chance,’ said young Gerry Pearce. ‘He stayed on his knees and kept praying.’

‘An Anglo-Catholic,’ said Aysgarth neutrally. ‘I noticed the pectoral cross.’

‘Talking of Anglo-Catholics,’ said Paul Dalton, ‘what a shocking piece of news that was about poor old Desmond …’

Desmond was discussed in suitably muted tones for a couple of minutes. Then since it was not the morning when we all attended the Communion service, the group dispersed. Gerry and Paul drifted away to their homes for breakfast. Tommy, who was that month the Canon ‘in residence’, responsible for the services, wandered off to make sure the new verger had set out the right quantities of wine and wafers. Only Aysgarth lingered, waiting to see what I was going to do. ‘Staying on, Charles?’ he enquired casually after Tommy had disappeared. ‘What about that train to London?’

‘I’m not leaving until I’ve seen Desmond.’ Making an enormous effort I forced myself to say: ‘I’m afraid our conversation earlier wasn’t one of our best efforts. I’m sorry.’

‘No need to apologise. Entirely my fault. I’m sorry too.’

How hard we were both trying to be Christian! And what a stilted, awkward job we were both making of it! In despair I wondered if I was even fit to receive the sacrament, but I knew this descent into gloom was unjustified. I repented of my earlier burst of anger; I wanted to attend Communion; I needed the comfort of the sacrament as I faced the long, arduous day which lay ahead.