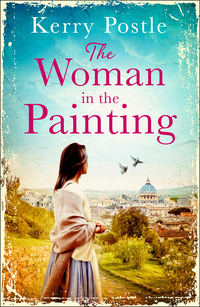

The Woman in the Painting

Though usually changeable in temper, events of the morning had made his humour worse than ever. I looked over to see him push the miniature of the artist from Urbino across the table in a fit of rage. It scraped across the surface, flew off the end, and crashed to the floor.

Not satisfied the miniature was on the floor, he kicked hard at it, pushing it away still further. Giulio sucked the air in through his teeth. The girl with the basket reddened. For the first time she appeared vulnerable. I was surprised.

Then I understood.

Sebastiano was jealous.

I looked at his blotchy face. His nose was an angry red and his eyes were incandescent with a rage so strong it threatened to consume him.

As for the girl’s cheeks, they returned from flush red to a warm pink the nearer she got to the door. She sprang by, determined not to be cowed by Sebastiano’s display of bad temper. She gave me a wink.

‘STOP … SWINGING … THE BASKET!’

Sebastiano’s voice boomed across the workshop like a clap of thunder.

In my shock I jumped. I have no idea what the dancing girl without the pearl earrings did because I froze. It was my heart that now lurched into my mouth – preferable to the contents of my stomach that had threatened to make a reappearance in response to something Giulio had said earlier.

I’d knocked over the lamp and I watched in horror as hot linseed oil surged from it to create the most perfect of arcs. It slipped through the air and landed in the uncovered lapis lazuli dust on the neighbouring bench. Its globular heaviness made the precious pigment puff up. Thousands of specks of exquisite colour cascaded before my eyes. It was as if time had slowed down as I watched this disaster unfold. When I’d looked back up from the now settled ultramarine powder the girl was nowhere to be seen. The main door slammed shut. She’d gone.

I turned to look at Giulio. Mockery had vanished from his eyes. Arrogance had abandoned him. He was looking behind me. His mouth opened as if to speak but it was as if the deluge of the shock within had flooded him so completely that no sound came out.

Then I felt it. Sebastiano’s heavy palm, slap, on the back of my head.

I stumbled forward, gasped for air. I sneezed, my nostrils irritated by the dust Giulio had produced after hours of grinding. Celestial dust. Colour of the heavens and the Madonna’s sacred robe. The most expensive pigment in all the world. And now it lay over the bench like a fine covering of newly fallen snow. The hand that had struck me wrapped itself around my upper arm and squeezed hard. I felt the gold ring on one of his fingers dig into me. I sneezed some more, unable to stop. I watched, appalled, as moisture now clung to the lapis dust to form dark, wet dots. The same hand that squeezed me shook me. Pain and shock rendered me breathless. Sebastiano had achieved his aim: I stopped sneezing. But by then it was too late.

I looked at Giulio. In my naivety I hoped that he might be able to do something, say something, that would save me: it was clear he could not. Invisible ropes had already started to pull him back to his place of work. His eyes looked on me with sympathy but his work-worn hands were securely tied. He had no choice but to watch as Sebastiano dragged me to the heavy oak door of the workshop and cast me outside. He threw my jacket after me.

‘Think yourself lucky I don’t get you locked up for this. The money you’ve lost me! Now clear off! Talentless dog that you are!’

As the door slammed shut behind me, I imagined my father’s knuckles cracking.

Chapter 4

I could not believe what had just happened. The injustice of it burned the backs of my eyes. What would Father say? What would he do to me? I lay there sprawled across the street, too afraid to move.

Passers-by walked round my fourteen-year-old body as I allowed Sebastiano’s taunts (preferable to those I anticipated from my father) to still ring in my ears. Some walked over me, tripping as they went. But I remained there, eyes shut tight, not knowing what to do next.

I must have been lying there for ages by the time someone gave in to temptation and decided to have some sport at my expense. A full-blown hammer foot made its way into my side. Winded, my eyes shot open. I spluttered, gasping for air and feeling like a pig’s bladder. ‘Look at you in your yellow hose!’ a cruel voice mocked. ‘You look like a g—’ But before he could finish someone had pulled him back, causing him to thud, backside first, on the ground. Laughter rippled all around. The disturbance was attracting quite a crowd.

‘Get off him! What are you doing, you filthy worm-head? Leave the poor devil alone!’ It was the girl in the painting, the one with the basket, she of the flour-hemmed skirt, and she was yelling and pushing my attacker away. ‘Get off with you! Get away! Kicking a lad when he’s down. Some brave man you are!’ People’s sympathies changed direction like ears of wheat as this feisty girl vented her rage towards my attacker. Shouts of agreement came from people in the street. The brave man who’d kicked me when I was down scrambled to his feet.

‘If you was a man and not a girl you would not be able to speak to me so,’ he snarled, half standing and wiping his nose with the back of his hand.

‘Well I am a girl,’ my saviour announced, ‘and I will shame you all the same!’

Sounds of approval rustled all around.

The man who’d used me as a kickball looked at the angry faces. The fear that what he had done to me might be done to him was etched deeply on his face. He turned heel and took flight.

The girl stooped down.

‘Thought I’d come back and make sure you were all right. Lucky I did! Here, let me help you.’ Careful not to let her basket out of sight she dragged me up to sitting. I reached out for my jacket and pulled it to me. ‘Feeling better?’

I nodded that I was, though that I couldn’t bring myself to speak told her that I wasn’t. I felt as though I’d received a stunning blow to the head and a crippling kick in the ribs, probably because I had. And I was now in shock, unable to comprehend what had befallen me. Yet my faithful, unwanted friend, humiliation, was slowly spreading across my body like a rash as the whole sorry experience came back to me. I hoped she hadn’t seen everything. Her hand on my shoulder, gentle and caring, told me she had.

‘You’re not like all them – them inside.’ She gestured to Sebastiano’s workshop with a tilt of her head.

The girl with the soft brown eyes had a soft, sweet voice, and although she intended for her words to comfort me, instead they thrust the knife in, gave it a turn. ‘You belong out here in the real world.’ I rubbed my side, a reminder of how painful the real world could be. Understanding flickered across the girl’s face. ‘Oh, that’s not what I meant!’ She laughed. I winced. ‘No! It’s just, well, I could tell when I saw you in there. You’re well, you’re more like, well, more like me, I suppose.’ I looked at her. She was pretty enough, certainly prettier than Sebastiano’s portrait of her, but her clothes, I saw for the second time that day, gave away her rank; no matter how clean they were, no amount of care could stop flour from clinging to the edge of her skirt, and patching only drew one’s attention to well-worn cloth. My hand went to brush some of the dust off my brightly coloured hose.

‘It’s better to be honest and have your self-respect intact than allow another person to treat you like an animal.’ She patted me on the arm as she chatted on about the virtues of being what I could only presume was like her. This repelled me at the time. But in my defence, upbringing had a large part to play in how I was thinking that day. As well as fear. I had been brought up by a father who constantly told me how he had married beneath himself and had lived to regret it. He’d got married for love, to a lowborn woman who had gone and died. She’d brought him no dowry, given him seven sons. ‘And then she died, giving birth to you!’ My father had shouted this at me often enough to make me realise he’d never forgiven either of us for that. My mother for leaving him, and me for staying alive.

I looked at this girl with the passably pretty face and the dress that she’d made good and kept washed. And I imagined my mother. I quickly pushed the thought away. That way danger lay. The woman was dead. No good would come of softening towards a memory, nor towards a girl with little to her name.

But she had saved me from the ruffians; that much was true. ‘Thank you … for chasing off those thugs.’

‘Oh, that was nothing. And there was only one of them. Besides, did you not see how we all came together to support you?’ The crowd had now dispersed but with a flourish of her hand this girl presented every passer-by to me as if each one of them was a saint or an avenging angel. ‘It’s the likes of Signor Importante in there that we both need to be wary of. The great maestro.’

An old woman walked by, and, overhearing our conversation, shouted out, ‘Si, ragazzo, no shame in being one of us. The people of Rome are the best in the world.’

Then, as if to prove it, a man with a donkey smiled at me, his weather-beaten face as brown and shiny as well-used leather. I waited for him to offer himself up as one of the self-righteous rabble. He did not disappoint. ‘Si, ragazzo, plebeian.’ He chuckled. ‘That’s what we are.’ His voice was as gravelly as the dirt roads he walked along, albeit streaked with a pride that, in my newly fallen state, I was far from understanding. For me it was as if I had been expelled from the Garden of Eden, while plebeian was a word my father used when describing my dead mother – and he didn’t mean it as a compliment.

I stared with longing at the large oak doors, now firmly shut behind me. The thought that Paradise was on the other side and that there was no longer any place for me there bored a hole in my heart. That Sebastiano should be cast as God was one of life’s little ironies – earthbound paradises had their drawbacks.

I shuddered.

The girl’s hand, still on my shoulder, felt the tremor within. ‘Artists! Who do they think they are? Gods?’ she cried, as if reading my thoughts. ‘Look at you, with your bright eyes!’

I lowered my eyelids to stop her from seeing any more. I looked down at my lamp-black-stained hands, the soot in and around my fingernails. As I hid them in the folds of my shirt I discovered the holes at the elbows of my tattered sleeves. My fingers slipped through to the bones. They stung to the touch, felt wet and sticky. I guessed they were bleeding. My eyes drifted up towards the hands and attire of the proud plebeian leading away his trusty steed that was no more a steed than I was now an artist’s apprentice, never mind an artist.

What was that saying my father liked so well? Something about every ass thinking himself worthy to stand with the nobleman’s horses? Well, I was the ass. The man’s clothes were no worse than my own, and, in many ways better, I realised, as my fingers now covered the recently made tears in my sleeves. But I still couldn’t think of myself as a plebeian, no matter what I looked like, no matter that I’d been cast out. Ass, yes. Plebeian, never. I rubbed my shoulder blades, half hoping to raise angel wings from beneath the skin, for in that moment to be a fallen angel far outshone life as a common man.

‘All right! Take it easy! I only wanted to make sure they hadn’t hurt you.’ I’d brushed the girl’s hand off my shoulder a little too brusquely while checking for feathers. The indignation in her voice pulled me back to myself.

‘Thank you. For stopping,’ I said again, remembering the tens of Rome’s finest who hadn’t.

‘It was nothing,’ she said, her voice soft once more.

‘My name is Pietro,’ I told her.

‘Margarita,’ she replied. Although I already knew that.

She held out a hand, helped me to my feet, then led me to the side of the street. I staggered slightly and leant against the wall to steady myself. To hope she hadn’t noticed was too much to ask for, that I knew already, but I had hoped for a little sensitivity in the way she addressed it. Instead she went for the blunt approach. ‘You’ve had the wind knocked out of you right enough,’ she said. ‘Your eyes look like cockroaches on a bedsheet. Your hair’s gone grey with the dust and your …’ but then she stopped mid-flow. And for that I was truly grateful.

My eyes, screwed up and looking for the ground beneath to gape open and swallow me whole, lifted to see what or who had caused this direct-talking girl to desist. Striding towards us was a papal party, as intimidating as an invading army, and there, at the head of the group, was a fierce-faced Cardinal, red robes flowing, his band of mercenaries marching behind him. The Cardinal’s eyes swivelled left and right, sweeping all before him. The disgust they registered as he looked upon me turned to desire as they fell upon Margarita. I thought I saw recognition cross his face. But if I did, it vanished as quickly as it had arrived.

Besides, by the time he looked at her again she had turned her back towards him, a gesture of defiance so flagrant I expected one of his thuggish entourage to drag her away by the hair. I was relieved when they didn’t. She was uncouth and lowborn, and to accept charity from such a person did kindle some sparks of resentment, but I was starting to appreciate her kindness and recognise its value – despite her unchecked tongue – in this city that to me seemed now full of hostility and danger.

‘That was Bibbiena.’ She almost spat the words out. That she had failed to say ‘Cardinal Bibbiena’ did not surprise me. I was beginning to get the measure of the girl. ‘The man’s a worm-head,’ she continued as she arched her neck after Bibbiena and his men. ‘Good. The piece of filth has gone. Time I was going too. You’ll be all right?’ she asked.

‘Of course,’ I lied, strangely invigorated by her use of the local vernacular. ‘I’ll take myself home and I’ll be fine.’

She put one hand on my shoulder again. I did not recoil. She nodded, satisfied with my answer. ‘Look after yourself, Pietro, and if you ever happen to be in Trastevere, come and say hello. My father runs a bakery there, on Via Santa Dorotea. His name’s Francesco Luti.’

‘Many thanks … Margarita. And you too … l-l-l …’ I could not say ‘look after yourself’. I satisfied myself with a repeated ‘many thanks.’ She smiled. She’d touched me and she knew it and she plunged her fingers in my dust-coated hair to acknowledge the fact, giving it a vigorous, sisterly ruffle before setting on her way. And with that she was gone, dancing her way along the street, head bobbing and dark brown hair rippling behind like a stream as she swung her basket up and down, all thoughts of Cardinal Bibbiena gone.

It was in my mind that I would probably never see this girl again, and, for the briefest of moments, this saddened me. I was rubbing at my eyes with the back of my hand, when I noticed a growing din coming from an exuberant group of young men. You had to be careful in Rome, even in the daytime. A cardinal and his followers was one thing, the arrival of noisy groups of men charging along the street was something else. It could herald danger for a boy on his own, a boy like me, no matter what Margarita believed.

Margarita. For a moment I hoped she would come back; she seemed more than capable of handling thugs. But as the sounds grew clearer it was evident that the approaching group did not have violence on their minds. Artists and apprentices, wielding nothing more dangerous than paintbrushes, paint, and paper, were heading towards me. Relief and trepidation flooded my senses in equal measure.

I put a hand up to shade my eyes for fear of being recognised and to hide their tell-tale puffiness. I needn’t have worried. Not a head turned my way. Every boy in the group had eyes only for their leader and they jostled with one another to get close to him.

As heads parted I saw him for myself. Even from afar, I understood why these young men were leaping like spring hares. There he was, a handsome young man, surrounded by excited young men dressed in the latest fashions, with him the most fashionable of them all. His brilliant white shirt billowed like a dazzling sail, his black velvet jacket was slung over his shoulder as if that was the way it was meant to be; his perfect hose were well tailored and, as my eyes fought to find a break lower down in the wall of bodies around him, I caught sight of well-sculpted calves. As for his hair, topped by a black velvet cap, he wore it longer than most young men of Rome at the time but it looked all the more attractive for that. Long, dark, and neat, it framed the most luminous of faces out of which shone the most beguiling of smiles. I watched him, transfixed.

And the closer he got the more I felt sure I knew him. Who was this beautiful man? I racked my brains. I’d seen him very recently. But where? At one of the studios? Had I happened across a likeness of him? That was it: the miniature portrait, the one Giulio had passed round only that morning. ‘Likes to pose more than paint! Look at him! Steals the ideas of others. No originality. The man’s a pretty-faced apprentice. Nothing else.’ I recalled the fierce red patches of resentment on Sebastiano’s face as he raged against the likeness of the clear-faced person here before me. Yes, I knew this man: it was the artist Raphael Sanzio.

Awe, warm and comforting, flooded my soul as Sebastiano’s ‘pretty-faced apprentice’ drew near, rapidly followed by an unpleasant chill; I recognised two of the boys vying to get close to him. A sense of shame lapped all around me with its icy waves. Luigi and Federico had been kicked out of Michelangelo’s workshop the same time as me. They’d had nowhere to go. The memory of my having sneered at them stung like a newly opened wound. They would have the last laugh now, if they saw me. I averted my eyes.

‘Pietro? It’s Pietro!’

Too late. Luigi had spotted me.

I looked at him with a weak smile, a nod of the head, and a feeling akin to gratitude that he seemed to have no intention of breaking away from the group to talk to me further. But then …

‘Is this man one of your friends?’ The dazzling figure at the centre of the group stopped dead some distance away from me, his voice cutting across the street. His followers stopped too, squashed in a huddle. I made to get away but my foot had gone to sleep, causing me to trip up. I fell. My nose was in the dirt. When I turned around Raphael was looking down on me.

Then I understood.

I saw for myself why the fools jostled to get close. Yes, to my fourteen-year-old mind it was as if all the virtues radiated from him. He was grace, truth, and beauty. The smile he gave me was unwavering, and so bright that I had to lower my eyes.

‘So this is Pietro, you say? It’s a pleasure to make your acquaintance, Pietro. My name is Raphael. From Urbino.’

I blinked up at him. Luigi, the boy who’d spotted me, nodded enthusiastically and pulled me up to sitting. Urbino. One word can evoke a whole world. Reputed to have the most civilised court in all of Europe, Urbino was where, it was said, manners, appearance, philosophy, and art had all combined to create this most perfect of artists. And here he was standing before me, the idea of perfection in human form. The white of his shirt dazzled me once more. I looked down upon my own apparel and saw the sorry tale it told. I had no need to say what I’d done, where I’d been, my dishevelled appearance said it all. I had tell-tale paint splashes all over, I was outside Sebastiano Luciani’s studio, I was covered in the dust and dirt of the street, and although I’d tried hard to swallow them back, tears had insisted on drawing lines down my face. I winced and wondered how this perfect courtier would manage to withdraw friendly overtures without the whole affair seeming awkward.

Instead he pressed me for my story. His followers listened attentively.

‘Your father is a potter? How interesting.’

‘Yes. And I-I-I …’ I felt the fire of embarrassment burn behind my cheeks. My infernal stammer!

‘He’s been apprentice to Michelangelo and Sebastiano.’ Luigi saved me.

‘Fine artists,’ Raphael said. ‘Two of the finest in all of Rome. The best, in fact,’ he continued, somewhat generously, I thought, as I knew both well enough to be certain that neither one of them would ever have said the same of him.

He placed a hand on my shoulder before retreating to confer with Luigi and Federico. I could not make out the words but their tone was gentle. When Raphael looked back at me, his eyes bore no trace of ridicule.

Their discussion was over.

‘It has been an honour and a privilege to make the acquaintance of such an experienced apprentice, Pietro. I hope—’ he placed a hand on my dust-stained shirt once again ‘—you might consider continuing your apprenticeship with me. With us.’

I smiled my gratitude as I knew words would fail me.

‘Now we’ll be off,’ Raphael said. ‘We will meet again very soon I hope, Pietro.’

I nodded – I could do nothing else – and I watched him as he led his followers away. When the last one of them had disappeared through the arch at the end of the street I noticed that the sky was clouding over. I’d better get home before the weather breaks, I thought to myself, and tell my father the good news.

Chapter 5

Most times you will hate me when I tell you my secrets and confess to the lies I have told, but once or twice, when I tell you what I have told no one else, you might find it in your hearts to pity me. What I’m about to tell you is one such time.

I should never have told him the truth, when I returned home, of what had happened to me that day. Or at least I should have told him the good news first. Either way, my story might have been very different, a tale of a potter father laughing, back-slapping and congratulating his talented son on being newly apprenticed to Rome’s most shining star. We would have celebrated carnival together, watched the processions trail past, and I could have pointed Raphael out to my father in the crowd. He would have showered me with paternal pride. I would have reciprocated with filial affection.

Instead, all that rained down on me was this.

‘You’re like her, like she used to be – weak! Useless! You take everything, give nothing.’ That was my father. I told you he’d never forgiven my mother for leaving him with seven sons to bring up. He went on. And on. I covered my ears to keep his brutal words at a muffled distance. But still his face contorted before my eyes. I closed them tight, turned them inwards desperately searching for somewhere to hide. But my father wouldn’t let me.

‘No more! You’re out! I’ll not have you here anymore.’ He screamed the words into my ears, causing a fire to rampage within. My eyes shot open.

‘Shut up!’ I wanted to scream in his face. ‘Shut up! Shut up! Shut up!’ Instead I begged my father not to cast me out. ‘P-p-p-please. Please d-d-d-don’t! I’m sorry, Father. Forgive me. Please. Father!’ But his clay-stained hand was already grasped tight around my arm, ready to throw me away and see me smash to the floor like a misshapen pot.

I’d told him how Sebastiano had treated me. His vice-like grip as his fingers pressed themselves into my flesh confirmed this had been a mistake. But if I told him about my good fortune in encountering Raphael from Urbino, I reasoned with myself, I could prevent the worst from happening. A threat to throw me out was, after all, just a threat.

‘But something g-g-g …’ I stumbled over my words again. I had a habit of doing so at times like this. It irritated me. But not as much as it irritated my father.

I dared not try to explain again. My only hope was to submit to his tirade and pray that he wouldn’t follow through and banish me from home completely.

‘Useless!’

My arm still in his grip, he shook me before releasing me with a savage push. Searing pain ran through my upper arm, across my shoulder and up my neck. I staggered forward. My instinct was to cry out but I knew I shouldn’t. I bit my tongue. Reined myself back in. I could hide my feelings, conceal how and who I was. I’d had to do so ever since I was small. And on the rare occasion when I’d failed to dissemble, silence had come to my aid. I prayed it would do so now.