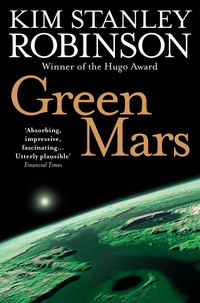

Green Mars

Afterward he walked down the streets of Sheffield bouncing erratically, feeling the nitrous champagne as a kind of anti-gravitational effect, which, added to the Martian baseline, made him feel altogether too light. Technically he weighed about forty kilos, but as he walked along it felt more like five. Very strange, even unpleasant. Like walking on buttered glass.

He nearly ran into a young man, slightly taller than him—a black-haired youth, as slender as a bird and as graceful, who quickly veered away from him and then steadied him with a hand to his shoulder, all in one smooth flow of movement.

The youth looked him in the eye. “Are you Arthur Randolph?”

“Yes,” Art said, surprised. “I am. And who are you?”

“I’m the one who contacted William Fort,” the young man said.

Art stopped abruptly, swaying to get back over his feet. The young man held him upright with a gentle pressure, his hand hot on Art’s upper arm. He regarded Art with a direct look, a friendly smile. Perhaps twenty-five, Art judged, perhaps younger—a handsome youth with brown skin and thick black eyebrows, and eyes that were slightly Asian, set wide over prominent cheekbones. An intelligent look, full of curiosity and a kind of magnetic quality, hard to pin down.

Art took to him instantly, for no reason he could tell. It was just a feeling. “Call me Art,” he said.

“And I am Nirgal,” the youth said. “Let’s go down to Overlook Park.”

So Art walked with him down the grassy boulevard to the park on the rim. There they strolled the path next to the coping wall, Nirgal helping Art with his drunken turns by frankly seizing his upper arm and steering him. His grasp had an electric penetrating quality to it, and was really very warm, as if the youth had a fever, though there was no sign of it in his dark eyes.

“Why are you here?” he asked—and his voice, and the look on his face, made the question into something other than a superficial enquiry. Art checked his response, thought about it.

“To help,” he said.

“So you will join us?”

Again the youth somehow made it clear that he meant something different, something fundamental.

And Art said, “Yes. Any time you like.”

Nirgal smiled, a quick delighted grin that he only partly overmastered before he said, “Good. Very good. But look, I’m doing this on my own. Do you understand? There are people who wouldn’t approve. So I want to slip you in among us, as if it were an accident. That’s okay with you?”

“That’s fine.” Art shook his head, confused. “That’s how I was planning on doing it anyway.”

Nirgal stopped by the observation bubble, took Art’s hand and held it. His gaze, so open and unflinching, was contact of another kind. “Good. Thanks. Just keep doing what you’re doing, then. Go out on your salvage project, and you’ll be picked up out there. We’ll meet again after that.”

And he was off, walking across the park in the direction of the train station, moving with the long graceful lope that all the young natives seemed to have. Art stared after him, trying to remember everything about the encounter, trying to put his finger on what had made it so charged. Simply the look on the youth’s face, he decided—not just the unself-conscious intensity one sometimes saw on the faces of the young, but more—some humorous power. Art remembered the sudden grin unleashed when Art had said (had promised) that he would join them. Art grinned himself.

When he got back to his room, he walked right to the window and opened the curtains. He went over to the table by his bed, and sat and turned on his lectern, and looked up Nirgal. No person listed by that name. There was a Nirgal Vallis, between Argyre Basin and Valles Marineris. One of the best examples of a water-carved channel on the planet, the entry said, long and sinuous. The word was the Babylonian name for Mars.

Art went back to the window and pressed his nose against the glass. He looked right down the throat of the thing, into the rocky heart of the monster itself. Horizontal banding of the curved walls, the broad round plain so far below, the sharp edge where it met the circular wall—the infinite shadings of maroon, rust, black, tan, orange, yellow, red—everywhere red, all the shades variations of red … He drank it in, for the first time unafraid. And as he looked down this enormous coring into the planet, a new feeling leaped into him to replace the fear, and he shivered and hopped in place, in a little dance. He could handle the view. He could handle the gravity. He had met a Martian, a member of the underground, a youth with a strange charisma, and he would be seeing more of him, more of all of them … He was on Mars.

And a few days later he was on the west slope of Pavonis Mons, driving a small rover down a narrow road that paralleled a band of disturbed volcanic rubble, with what looked like a cog railway track running right down it. He had sent a final coded message to Fort, telling him that he was taking off, and had got the only reply of his journey so far: Have a nice trip.

The first hour of his drive held what everyone had told him would be its most spectacular sight: going over the western rim of the caldera, and starting down the outer slope of the vast volcano. This occurred about sixty kilometres west of Sheffield. He drove over the southwest edge of the vast rim plateau, and started downhill, and a horizon appeared very far below, and very far away—a slightly curved hazy white bar, like the view of Earth as seen from a space plane’s window. This made sense, as the peak of Pavonis was about as far above Amazonis Planitia as space planes often flew over Earth in their jet phase—some 85,000 feet high. So it was a huge view, the most forcible reminder possible of the stupendous height of the Tharsis volcanoes. And he had a great view of Arsia Mons at that moment, in fact, the southernmost of the three volcanoes lined up on Tharsis, bulking over the horizon to his left like a neighbouring world. And what looked like a black cloud, over the far horizon to the northwest, could very possibly be Olympus Mons itself! An amazing view.

So the first day’s drive was all downhill, but Art’s spirits remained high. “Toto, there is no chance we are in Kansas any more. We’re … off to see the wizard! The wonderful wizard of Mars!”

The road paralleled the fall line of the cable. The cable had hit the west side of Tharsis with a tremendous impact, not as great as during the final wrap of course, but enough to create the interesting superbuckies Art had been sent out to investigate. The Beast he was going down to meet had already salvaged the cable in this vicinity, however, and the cable was almost entirely gone; the only thing left of it was a set of old-fashioned-looking train tracks, with a third cog rail running down the middle. The Beast had made these tracks out of carbon from the cable, and then used other parts of the cable, and magnesium from the soil, to make little self-powered cog rail mining cars, which then carried salvage cargo back up the side of Pavonis to the Ouroborous facilities in Sheffield. Very neat, Art thought as he watched a little robot car roll past him in the opposite direction, up the tracks toward the city. The little train car was black, squat, powered by a simple motor engaging the cog track, filled with a cargo of carbon nanotube filaments, and capped on top by a big rectangular block of a diamond. Art had heard about this in Sheffield, and so was not surprised to see it. The diamond had been salvaged from the double helixes strengthening the cable, and the blocks were actually much less valuable than the carbon filament stored underneath them—basically a kind of fancy hatch door. But they did look nice.

On the second day of his drive, Art got off the immense cone of Pavonis, and onto the Tharsis bulge proper. Here the ground was much more littered than the volcano’s side had been with loose rock, and meteor craters. And down here, everything was blanketed with a drift of snow and sand, in a mix that looked like equal shares of both. This was the firn slope of west Tharsis, an area where storms coming in from the west frequently dumped loads of snow, which never melted but instead built up year by year, packing down the snow on the bottom. So far the pack consisted only of crushed snow, called firn, but a few more years of compaction and the lowest layers would be ice, and the slopes glaciers.

Now the slopes were still punctuated by big rocks sticking out of the firn, and small crater rings, the craters mostly less than a kilometre across, and looking as fresh as if they had been blasted the day before, except for the sandy snow now filling them.

When he was still many kilometres away, Art caught sight of the Beast salvaging the cable. The top of it appeared over the western horizon, and over the next hour the rest of it reared into view. Out on the vast empty slope it seemed somewhat smaller than its twin up in East Sheffield, at least until he drove under its flank, when once again it became clear that it was as big as a city block. There was even a square hole in the bottom of one side which looked for all the world like the entrance to a parking garage. Art drove his rover right at this hole—the Beast was moving at three kilometres a day, so it was no trick to hit it—and once inside, he drove up a curving ramp, following a short tunnel into a lock. There he spoke by radio to the Beast’s AI, and doors behind his rover slid shut, and in a minute he could simply get out of his car, and go over to an elevator door, and take an elevator up to the observation deck.

It did not take long to realise that life inside the Beast was not the essence of excitement, and after checking in with the Sheffield office, and taking a look at the ion chromatograph down in the lab, Art went back out in the rover to have a more extensive look around. This was the way things went when working the Beast, Zafir assured him; the rovers were like pilot fishes swimming around a great whale, and though the view from the observation deck was nice and high, most people ended up spending a good part of their days out driving around.

So Art did that. The fallen cable out in front of the Beast showed clearly how much harder it had been coming down here than it had back at the start of its fall. Here it was buried to perhaps a third of its diameter, and the cylinder was flattened, and marked by long cracks running along its sides, revealing its structure which consisted of bundles of bundles of carbon nanotube filament, still one of the strongest substances known to materials science, though apparently the current elevator’s cable material was stronger yet.

The Beast straddled this wreckage, about four times as tall as the cable; the charred black semi-cylinder disappeared into a hole at the front end of the Beast, from which came a grumbling, low, nearly subsonic vibration. And then, every day at about two in the afternoon, a door at the back of the Beast slid open over the tracks always being excreted from the back end of the Beast, and one of the diamond-capped train cars would roll out and glide off toward Pavonis, winking in the sunlight. The trains disappeared over the high eastern horizon (into the apparent “depression” now between him and Pavonis) about ten minutes after emerging from their maker.

After viewing the daily departure, Art would take a drive in the pilot fish rover, investigating craters and big isolated boulders, and, frankly, looking for Nirgal, or rather waiting for him. After a few days of this, he added the habit of suiting up, and taking a walk outside for a few hours every afternoon, strolling beside the cable or the pilot fish, or hiking out into the surrounding countryside.

It was odd-looking terrain, not only because of the even distribution of millions of black rocks, but because the hard blanket of firn had been sculptured into fantastic shapes by the sand-blaster winds: ridges, boles, hollows, tear-shaped tailings behind every exposed rock, etc. Sastrugi, they were called. It was fun to walk around among these extravagant aerodynamic extrusions of reddish snow.

Day after day he did this. The Beast ground slowly westward. He found that the windswept bare tops of the rocks were often coloured by tiny flakes that were scales of fast lichen, a kind that grew quickly, or at least quickly for lichen. Art picked up a couple of sample rocks, and took them back into the Beast, and read about the lichen curiously. These apparently were engineered cryptoendolithic lichens, and at this altitude they were living right at the edge of the possible—the article on them said that over ninety-eight percent of their energy was used simply to stay alive, with less than two percent going toward reproduction. And this was a big improvement over the Terran template species.

More days passed, then weeks; but what could he do? He kept on collecting lichen. One of the cryptoendoliths he found was the first species to survive on the Martian surface, the lectern said, and it had been designed by members of the fabled First Hundred. He broke apart some rocks to have a better look, and found bands of the lichen growing in the rocks’ outer centimetre: first a yellow stripe right at the surface, then a blue stripe under that, then a green one. After that discovery he often stopped on his walks to kneel and put his faceplate to coloured rocks sticking up out of the firn, marvelling at the crusty scales and their intense pale colours—yellows, olives, khaki greens, forest greens, blacks, greys.

One afternoon he drove the pilot fish far to the north of the Beast, and got out to hike around and collect samples. When he returned, he found that the lock door in the side of the pilot fish would not open. “What the hell?” he said aloud.

It had been so long that he had forgotten that something was supposed to happen. The happening had taken the form of some kind of electronic failure, apparently. Assuming this was the happening, and not … something else. He called in over the intercom, and tried every code he knew on the keypad by the lock door, but nothing had any effect. And since he couldn’t get back in, he couldn’t turn on the emergency systems. And his helmet’s intercom had a very limited range—the horizon, in effect—which down here off Pavonis had shrunk to a Martian closeness, only a few kilometres away in all directions. The Beast was well over the horizon, and though he could probably walk to it, there would be a section of the hike where both Beast and pilot fish would be over the horizon, and himself alone in a suit, with a limited air supply …

Suddenly the landscape with its dirty sastrugi took on an alien, ominous cast, dark even in the bright sunshine. “Well hell,” Art said, thinking hard. He was out here, after all, to get picked up by the underground. Nirgal had said it was going to look like an accident. Of course this was not necessarily that accident, but whether it was or it wasn’t, panic was not going to help. Best to make the working assumption that it was a real problem, and go from there. He could try walking back to the Beast, or he could try getting into the pilot fish rover.

He was still thinking things over, and typing at the keypad of the lock door like a champion speed-typist, when he was tapped hard on the shoulder. “Aaa!” he shouted, leaping around.

There were two of them, in walkers and scratched old helmets. Through their faceplates he could see them: a woman with a face like a hawk’s, who looked as if she would be happy to bite him; and a short thin-faced black man, with grey dreadlocks crowding the border of his faceplate, like the rope picture frames one sometimes saw in nautical restaurants.

It was the man who had tapped Art on the shoulder. Now he lifted three fingers, pointing at his wrist console. The intercom band they were using, no doubt. Art switched it on. “Hey!” he cried, feeling more relieved than he ought to, considering that this was probably Nirgal’s set-up, so that he had never been in danger. “Hey, I seem to be locked out of my car? Could you give me a lift?”

They stared at him.

The man’s laugh was scary. “Welcome to Mars,” he said.

PART THREE Long Runout

Ann Clayborne was driving down the Geneva Spur, stopping every few switchbacks to get out and take samples from the roadcuts. The Transmarineris Highway had been abandoned after ’61, as it now disappeared under the dirty river of ice and boulders covering the floor of Coprates Chasma. The road was an archaeological relic, a dead end.

But Ann was studying the Geneva Spur. The Spur was the final extension of a much longer lava dike, most of which was buried in the plateau to the south. The dike was one of several—the nearby Melas Dorsa, the Felis Dorsa farther east, the Solis Dorsa farther west—all of them roughly parallel, all perpendicular to the Marineris canyons, and all mysterious in their origin. But as the southern wall of Melas Chasma had receded, by collapse and eolian removal, the hard rock of one dike had been exposed, and this was the one named the Geneva Spur, which had provided the Swiss with a perfect ramp to get their road down the canyon wall, and was now providing Ann with a nicely exposed dike base. It was possible that it and all its companion dikes had been formed by concentric fissuring resulting from the rise of Tharsis; but they could also be much older, remnants of a basin-and-range type spread in the earliest Noachian, when the planet was still expanding from its own internal heat. Dating the basalt at the foot of the dike would help answer the question one way or the other.

So she drove a little boulder car slowly down the frost-covered road. The car would be quite visible from space, but she didn’t care. She had driven all over the southern hemisphere in the previous year, taking no precautions except when approaching one of Coyote’s hidden refuges to resupply. Nothing had happened.

She reached the bottom of the Spur, only a short distance from the river of ice and rock that now choked the canyon floor. She got out of the car and tapped away with a geologist’s hammer at the bottom of the last roadcut. She kept her back to the immense glacier, and did not think of it. She was focused on the basalt. The dike rose before her into the sun, a perfect ramp to the clifftop, some three kilometres above her and fifty kilometres to the south. On both sides of the Spur the immense southern cliff of Melas Chasma curved back in huge embayments, then out again to lesser prominences—a slight point on the distant horizon to the left, and a massive headland some sixty kilometres to the right, which Ann called Cape Solis.

Long ago Ann had predicted that greatly accelerated mass wasting would follow any hydration of the atmosphere, and on both sides of the Spur the cliff gave indications that she had been right. The embayment between the Geneva Spur and Cape Solis had always been a deep one, but now several fresh landslides showed that it was getting deeper fast. Even the freshest scars, however, as well as all the rest of the fluting and stratification of the cliff, were dusted with frost. The great wall had the coloration of Zion or Bryce after a snowfall—stacked reds, streaked with white.

There was a very low black ridge on the canyon floor a kilometre or two west of the Geneva Spur, paralleling it. Curious, Ann hiked out to it. On closer inspection the low ridge, no more than chest-high, did indeed appear to be made of the same basalt as the Spur. She took out her hammer, and knocked off a sample.

A motion caught her eye and she jerked up to look. Cape Solis was missing its nose. A red cloud was billowing out from its foot.

Landslide! Instantly she started the timer on her wristpad, then knocked the binocular hood down over her faceplate, and fiddled with the focus until the distant headland stood clear in her field of vision. The new rock exposed by the break was blackish, and looked nearly vertical; a cooling fault in the dike, perhaps—if it too was a dike. It did look like basalt. And it looked as if the break had extended the entire height of the cliff, all four kilometres of it.

The cliff face disappeared in the rising cloud of dust, which billowed up and out as if a giant bomb had gone off. A distinct boom, almost subsonic, was followed by a faint roaring, like distant thunder. She checked her wrist; a little under four minutes. Speed of sound on Mars was 252 metres per second, so the distance of sixty kilometres was confirmed. She had seen almost the very first moment of the fall.

Deep in the embayment a smaller piece of cliff gave way as well, no doubt triggered by shock waves. But it looked like the merest rockfall compared to the collapsed headland, which had to be millions of cubic metres of rock. Fantastic to actually see one of the big landslides—most areologists and geologists had to rely on explosions, or computer simulations. A few weeks spent in Valles Marineris would solve that problem for them.

And here it came, rolling over the ground by the edge of the glacier, a low dark mass topped by a rolling cloud of dust, like timelapse film of an approaching thunderhead, sound effects and all. It was really quite a long way out from the cape. She realised with a start that she was witnessing a long runout landslide. They were a strange phenomenon, one of the unsolved puzzles of geology. The great majority of landslides move horizontally less than twice the distance they fall; but a few very large slides appear to defy the laws of friction, running horizontally ten times their vertical drop, and sometimes even twenty or thirty. These were called long runout slides, and no one knew why they happened. Cape Solis, now, had fallen four kilometres, and so should have run out no more than eight; but there it was, well across the floor of Melas, running downcanyon directly at Ann. If it ran only fifteen times its vertical drop, it would roll right over her, and slam into the Geneva Spur.

She adjusted the focus of her binoculars for the front edge of the slide, just visible as a dark churning mass under the tumbling dustcloud. She could feel her hand trembling against her helmet, but other than that she felt nothing. No fear, no regret—nothing, in fact, but a sense of release. All over at last, and not her fault. No one could blame her for it. She had always said that the terraforming would kill her. She laughed briefly, and then squinted, trying to get a better focus on the front edge of the slide. The earliest standard hypothesis to explain long runouts had been that the rock was riding over a layer of air trapped under the fall; but then old long runouts discovered on Mars and Luna had cast doubts on that notion, and Ann agreed with those who argued that any air trapped under the rock would quickly diffuse upward. There had to be some form of lubricant, however, and other forms proposed had included a layer of molten rock caused by the slide’s friction, acoustic waves caused by the slide’s noise, or merely the extremely energetic bouncing of the particles caught on the slide’s bottom. But none of these were very satisfactory suggestions, and no one knew for sure. She was being approached by a phenomenological mystery.

Nothing about the mass approaching her under the dustcloud indicated one theory over another. Certainly it wasn’t glowing like molten lava, and though it was loud, there was no way of judging whether it was loud enough to be riding on its own sonic boom. On it came in any case, no matter what the mechanism. It looked as though she was going to get a chance to investigate in person, her last act a contribution to geology, lost in the moment of discovery.

She checked her wrist, and was surprised to see that twenty minutes had passed already. Long runouts were known to be fast; the Blackhawk slide in the Mojave was estimated to have travelled at 120 kilometres per hour, going down a slope of only a couple of degrees. Melas was in general a bit steeper than that. And indeed the front edge of the slide was closing fast. The noise was getting louder, like rolling thunder directly overhead. The dustcloud reared up, blocking out the afternoon sun.